6

Sultans, suzerains and the

colonial division of New Guinea

Introduction

This chapter is the first of the geographical presentations. It provides a history of how one of the Spice Island sultans became the putative suzerain of part of New Guinea. The chapter begins with the demise of the spice trade in the Spice Islands. Trade emphasis then changes to supplying goods to China, then to plumes, copra and other products for European markets. A growing European interest in tropical products resulted in the control of New Guinea being divided amongst the Dutch, German and British governments.

The decline of the Ternatian and Bacan sultanates and the rise of Tidore

As mentioned in Chapter 2, in 1653 the Sultans of Ternate and Bacan were required by the Dutch East India Company to destroy all the clove trees in their territories. They also had to provide the labour for this work under Dutch supervision.1 To compensate for their lost spice income the Dutch East India Company agreed to pay both Sultans an annual subsidy. A similar arrangement was made with Tidore, but there was a short delay until the new sultan ascended the throne in 1657.

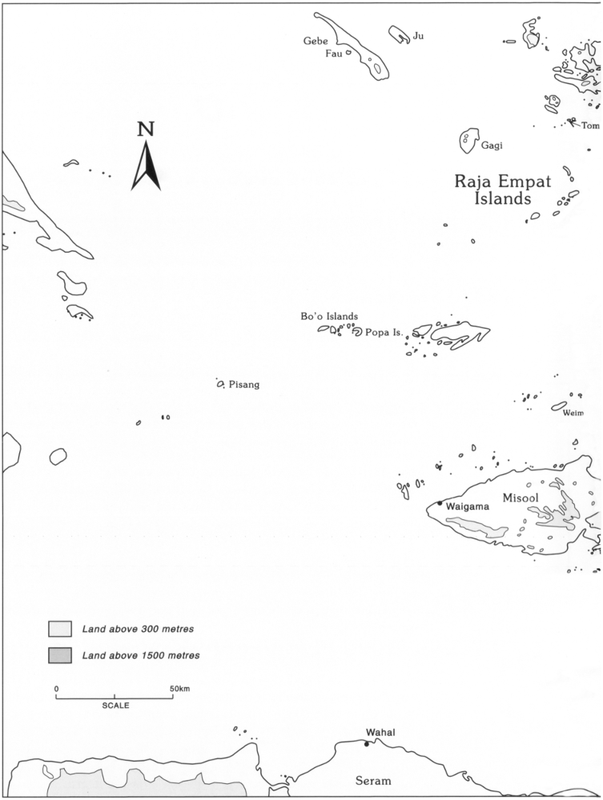

The Dutch East India Company made their first formal treaty with the new Sultan of Tidore after ousting the Spanish-Portuguese representatives from Tidore in 1660. In this treaty the Sultan of Tidore was made responsible for troublesome ‘Papua’, namely all the islands at the tip of western New Guinea, apart from the islands of the ‘Pigaraja’. The latter is generally accepted to mean the Raja of Misool (Figure 21), who remained under Bacan.2 This was the first of a number of treaties. After 1761 the geographic area encompassed by each new treaty increased as the Dutch perceived a growing interest by other metropolitan powers in the Pacific, see Figure 22.110

Figure 22: The Raja Empat Islands111

112The choice of Tidore is interesting, as it was the Sultan of Bacan and not Tidore who had real influence in the troublesome Raja Empat Islands. The Sultan of Tidore had no presence in the area. This suggests that other factors drove the Dutch East India Company to select the Sultan of Tidore. He was of course their man as the Dutch East India Company had influenced proceedings when the new sultan was chosen. By ensuring his success, it must be presumed that the Company expected to gain some advantage. Another factor in Tidore’s favour was that unlike the Sultan of Bacan, he was not closely associated with Ternate, the sultanate which had given rise to so many rebellions against the Dutch.

The Company expected the Sultan of Tidore to relieve them of the responsibility of maintaining law and order in the unprofitable Papuan Islands. Attempts to find precious metals or spices in New Guinea had been unsuccessful. Many company ships had been despatched to investigate the island’s resources, but apart from massoy (see Chapter 8), no profitable products had been found.

A new treaty was signed between the Dutch East India Company and the Sultan of Tidore in 1667. It is vague about the area under the Sultan’s jurisdiction. Such vagueness was clearly intentional, as it allowed the Company to make him responsible for all Papuan misdemeanours.3

When Keyts visited western New Guinea in 1678 he found no evidence of Tidore’s influence. The Governor of Banda also states in 1679 that the Sultan of Tidore did not have to be consulted when dealing with Papuans. However people in the Papuan Islands clearly feared him for his piracy and hongi raids.

By 1680 the Dutch East India Company had left trade with New Guinea to the Dutch planters on Banda, but their trading ventures ceased when a number of traders were killed. The treaty of 1667 between the Dutch East India Company and the Sultan of Tidore was renewed in 1689. In 1700 yet another contract was signed. This stipulated that the Sultan had to keep hostilities between the inhabitants of the Papuan Islands to a minimum. In 1703 Tidore’s representatives were allowed to travel with Company officials to New Guinea. This was the beginning of a practice which was to continue for the next two centuries.4

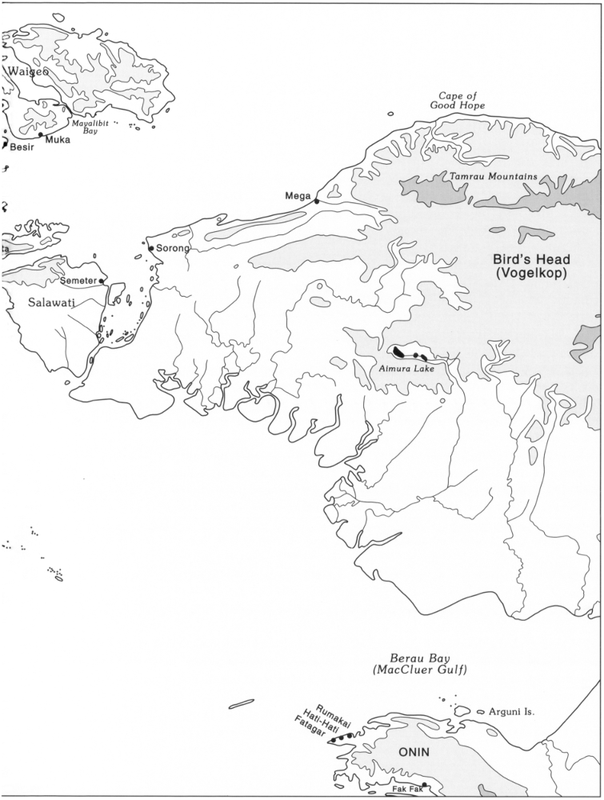

In 1706 Governor Rooselaar named the following islands as being under the rule of Tidore: Pisang, the 23 Bo (Bo’o) Islands, Popa, Misool, Salawati, Batanta and Waigeo.5 It is significant that neither Gebe nor the Onin peninsula of New Guinea are mentioned. Later in 1716, the Governor of the Residency of Ternate wrote that the Sultan of Tidore pretends to dominate part of the Bird’s Head, but even he admits that the Papuans do not recognise this claim.6

113Despite the Sultan of Tidore’s lack of authority in the Papuan Islands and western New Guinea, the Dutch renewed their contract with him in 1733. It was a far from satisfactory situation: the Sultan of Tidore had neither the respect of the people he was supposed to rule, nor an honest relationship with the Dutch. To obtain influence and intelligence the Sultan sent representatives to the Raja Empat Islands. When the Sultan’s representatives were present, these islanders were afraid to make any critical comments about the Sultan to Dutch officials, as they feared retribution.7

In 1761 the Dutch Government reassessed the rights of the Dutch East India Company in the eastern East Indies. They were concerned about the growing foreign threat to their spice monopoly. Their apprehensions were correct as a French expedition and subsequent English rule of the East Indies resulted in spice plants being collected and plantations being established elsewhere (see Chapter 2).8

In the late eighteenth century the Dutch only allowed Chinese traders from Ternate and Tidore to trade in New Guinea. They were permitted to do so on the grounds that they would not trade in nutmegs. The Chinese were permitted to trade for massoy bark, slaves, ambergris, trepang, turtle shell, pearls, parrots and birds of paradise. In return for these goods they gave iron tools, chopping knives, axes, blue and red cloth, beads, plates and bowls.9

It was Dutch policy to give as much power as possible in Papuan affairs to the Sultan of Tidore. By doing so, the Dutch hoped that he would become a local authority who could be held responsible for all Papuan offences. Dutch unification policies also expanded the area under Tidore’s jurisdiction. These expansions were not always welcomed by the Sultan. The locals likewise had no say in the matter. According to Thomas Forrest,10 who was in the Raja Empat Islands and visited Doreri Bay in 1774–5, the Papuans did not like the Tidorese. Despite being supported by the Dutch, the Sultan of Tidore was still unable to assert influence on Onin in 1775 without informing the Sultan of Misool.

The Dutch East India Company’s worries about protecting the Moluccas from foreign vessels increased when internal problems began to escalate. The Company tried to stop the Raja Empat Islanders from carrying out plundering raids by punishing their leaders. In 1770 they imprisoned the Raja of Salawati and in 1774 the Company arrested and exiled the Raja of Waigeo.11 In view of subsequent events these efforts had little impact. Papuan raids continued. There was also an increase in the number of raids from Sulu and Mindanao. The real problem came when a successor to the late Sultan of Tidore had to be chosen. Prince Nuku became angry when he was unsuccessful.

114In 1781 Nuku left Tidore and declared himself Sultan of the Papuan Islands. This was the beginning of a guerilla war which lasted for many years. The Papuans sided with the rebellious Prince Nuku. As a result Gebe and Numfor were able to extend their sphere of influence. During these chaotic years Gebe assembled a fleet of 300 praus which went on plundering sea raids.

In 1780 a contract was made between the Dutch East India Company and the new Sultan of Tidore which stated that his authority extended to all the villages on New Guinea. This claim was never repeated in subsequent treaties and was probably made to thwart Prince Nuku. At first things went badly for Prince Nuku. He was defeated by Tidore and lost Salawati in 1789, and in 1790 Misool submitted to Tidore. The relationship between Bacan and the Raja Empat Islands, especially Misool, was now over.

The British were able to enter the waters of the Dutch East Indies legally after the Dutch had signed the Treaty of Paris in 1784. This treaty required the Dutch to allow free navigation in the archipelago. In 1791 John MacCluer sailed past the Bird’s Head and explored Berau Bay (formerly MacCluer Gulf). In 1793 he returned with Captain John Hayes and Captain Court to found the first European settlement in New Guinea. These British East India Company entrepreneurs had obtained permission from Prince Nuku before attempting to establish their spice plantation at Doreri Bay. Hayes had a handful of British sailors and Indian soldiers under his command. They built a stockade called Fort Coronation in Doreri Bay (Figure 25) and took possession of the area he called New Albion. The fort had a wooden palisade and was defended by 12 cannons. New Guineans were ‘recruited’ to plant and tend spices, to harvest local wild nutmegs and cut teak. The venture was not a success. The supply of provisions did not go as planned. There were many deaths from malaria and beriberi, and some men were attacked, captured and sold as slaves. Some of those captured were sold by Numfor islanders on Seram. The base was abandoned in April 1795.12

Alternating British and Dutch control of the East Indies

In 1795 the Netherlands were occupied by Napoleon’s forces, and thus at war with Great Britain. That same year the British based some of their ships at Prince Nuku’s headquarters on Gebe. In 1796 and 1797 Prince Nuku with the assistance of two British ships captured all the government posts in the Moluccas, except Ternate which was not taken until June 1801.

In 1798 Prince Nuku proclaimed a man from Makian island as the Raja of Jailolo. The former Jailolo sultanate had ceased to exist after its 115sacking in 1551 by Ternatian and Portuguese forces following a combined Tidore, Jailolo and Spanish attempt to oust the Portuguese. Prince Nuku wanted the new Raja of Jailolo to undermine Ternatian support on Halmahera and in this way weaken the combined power of the Dutch and Ternatians. The Raja of Jailolo and all the successors to his title persisted in this endeavour until the last Raja of Jailolo was exiled in 1832. These efforts won support in Halmahera, especially the Tobelo region, the Raja Empat Islands, north and east Seram, Mindanao and the Sulu Archipelago.13

The East Indies were returned to Dutch control in 1802 when a peace treaty was signed at Amiens. As the Dutch East India Company had been disbanded in the Netherlands in December 1799, their assets became the responsibility of the Board of Asian Possessions. A colonial government was established when the Dutch resumed control of the archipelago in 1802, but this only lasted until 1810 when another European war began.

During the short Dutch administration, Prince Nuku died at Tidore in 1805. The so-called Raja of Jailolo continued Nuku’s pretence to the throne and resisted the Dutch until 1806 when he fled and found assistance in the Raja Empat group.

In 1810 the British regained what they called East India. In 1814 an agreement was made with the legitimate Sultan of Tidore and the Sultan of Ternate before the British Resident. The area of the Sultan of Tidore was described as comprising the islands of Maijtara, Filongan, Mare, Moa, Gebe, Joy (Ju), Pisang, Gagi, Bo’o, Popa, together with the whole of the Papuan Islands and the four districts of Mansary, Karandefur, Ambarpura and Umbarpon (Rumberpon) on the coast of New Guinea (Figure 21 bottom).14 The latter are thought to refer to the Numfor colonies on the west coast of Cendrawasih Bay and on Japen.15

The Dutch colonial government from 1814

The Dutch regained control of the archipelago in August 1814 and reestablished their colonial government. It was not until 1817 that a new treaty was signed with the Sultan of Tidore. The problem of the Sultan of Jailolo remained, but it soon became apparent that he had no real political ambitions and was no more than a pirate.

By 1817 the Dutch Residency of Ternate consisted of the self-governing sultanates of Ternate, Tidore and Bacan, as well as their subjected territories. These included Halmahera and adjacent islands, the Raja Empat group, the Sula archipelago and east Sulawesi. Dealings between the self-governing sultanates and the Dutch colonial government were regulated by contracts drawn-up with the Sultans of Ternate, Tidore and Bacan. Their subjected territories, however, were 116more or less under the total control of their own rulers. The Dutch considered the overall situation far from satisfactory, but did not instigate changes because of a lack of personnel and finance. This lack of activity reflected the limited economic interest shown by the Dutch in these areas.16

Further contracts were signed with Ternate and Tidore in 1824 which reiterated and strengthened the agreements of 1814 regarding their areas of suzerainty.

In 1824 the Netherlands and England came to an agreement that the Dutch had a right to part of New Guinea as stated in the treaty of 1814. It was also agreed that most of the island still remained ‘free’ in that it was not claimed by any metropolitan power.

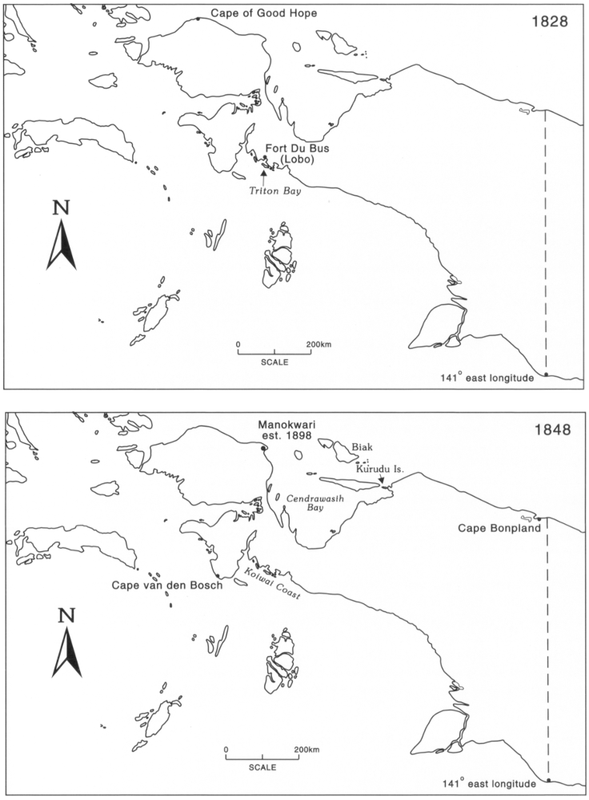

In 1828 the Dutch government claimed sovereignty of New Guinea from the Cape of Good Hope on the Bird’s Head to 141° east longitude on the south coast (near the current international border with Papua New Guinea) and the lands within (Figure 23 top). This event took place near Lobo in Triton Bay at Fort Du Bus on 24 August 1828. The fort was established by a military detachment dropped off from the Triton and Iris. The history of suffering experienced by the personnel of this settlement is well known. There was much illness and many died. In the eight years before the fort was abandoned and demolished in 1836, some 10 Dutch officers, 50 Dutch and 50 Indonesian soldiers died.17

After 1828 the area under the Sultan of Tidore’s authority was not described by the Dutch in any of the contracts made between them. In 1828 Dutch administrative officials began travelling in warships along New Guinea’s coastline. In addition to confirming the appointment of headmen on behalf of the Sultan of Tidore, they punished slave hunting and head-hunting. In 1830 Tidore defeated Gebe, the former headquarters of Prince Nuku. In 1832 the Sultan of Jailolo was sent into exile.

In the 1840s the Dutch government requested information as to the areas where Dutch colonial rule was accepted.18 This survey started in the Moluccas. In a secret report made in 1848 it was stated that Tidorese rule extended along the north coast of New Guinea until Cape Bonpland at 140°47' east longitude (Figure 23 bottom).

Bruyn de Kops was a lieutenant on the Circe, the Dutch man-of-war which accompanied the Tidorese hongi fleet on a weather-thwarted attempt to mark the extent of the north coast reputedly now under the Sultan of Tidore.19 In a secret decision made on 30 July 1848 the notion that Tidorese rule extended along the north coast of New Guinea as far as Cape Bonpland on the eastern side of Humboldt Bay was accepted by the Dutch government, without any further clarification. The Dutch did not make this eastern border public until 1865 and they were also very vague as to what areas came under Tidore’s jurisdiction or directly under the umbrella of Dutch rule.117

Figure 23: The respective areas of New Guinea designated under Tidore by the 1828 and 1848 treaties between the Dutch and Tidore.

118Although he did not interfere with trade, the Sultan of Tidore began to assert his authority, with Dutch backing, over western Dutch New Guinea in 1848. He did this by issuing levies (tribute demands) which were enforced by punitive hongi trips of rape and pillage. In New Guinea some of the worst raids were made on the easternmost areas of foreign trade, namely Kurudu Island on the north coast and the Kowiai area on the southwest coast (see Figure 23 bottom and Chapters 8 and 11). When the Dutch authorities forbade hongi expeditions, the influence of the Sultan of Tidore in western New Guinea soon ceased.20

The tribute demanded by Tidore had to be taken to the Sultan. Dumont D’Urville records that each ‘chief in Doreri Bay sent an annual tribute to this Sultan. Their tribute was a slave of either gender, turtle shell and bird of paradise skins.21 Sometimes this obligation was not met, thus provoking the notorious expeditions of the Tidorese fleets to Cendrawasih Bay. Sometimes fleets from Gebe and east Halmahera would make independent raids claiming to be acting under instruction from Tidore.

When the leaders from Cendrawasih Bay took their tribute to Tidore, they usually received a title in return. Initially these titles referred to real functions such as prince, head of a district or village headman. A flag and official dress went with each title. The Biak people, for example, later conferred similar titles on their trading friends. In this way these titles came to lose their functional associations.22

By 1858 the Sultan of Ternate lived in a large, untidy, half ruined stone palace. The Dutch government continued to pay him a pension. His suzerainty now only extended to the local people of Ternate and northern Halmahera. In the 1850s Dutch interests dominated the economy of Ternate. Over half of Ternate town was owned by a locally born Dutchman called Renesse van Duivenboden. He was known as the King of Ternate, which is not surprising as his possessions included land, ships and over 100 slaves. Much of his money was made by trading in plumes and natural history specimens as described in Chapter 4. When Alfred Russel Wallace travelled along the north coast of New Guinea, he went in the trading schooner Hester Helena which belonged to Duivenboden.23

Increasing Dutch presence in New Guinea from the 1850s

In 1855 C.W. Ottow and J.G. Geissler started mission work on Mansinam Island in Doreri Bay. Dutch navy vessels also began to increase the frequency of their visits. These voyages revealed how undesirable and disastrous Tidorese rule was and how it was not locally desired. The Dutch government put pressure on Tidore to stop 119using hongi fleets and their slave crews in the 1850s. In enforcing this ban the Dutch were following a worldwide trend, namely the growing abhorrence of slavery. Here we must remember that Britain passed anti-slavery laws in 1807, followed by the United States in 1808. British slaves were freed in 1838, French in 1848, Dutch in 1863 and American in 1865.24

Piracy and raiding declined when the Dutch began to use steamboats. In 1876 a member of Raja Jailolo’s family dano Babo Hasan tried to re-establish the sultanate on eastern Halmahera. His movement was directed against Ternate and Tidore, but was suppressed by the crew of a Dutch steamboat in 1877.25 The decline in piracy and hongi fleets saw an extension of trade along the north coast.

In the 1872 contract with Tidore it is made clear that the Sultan of Tidore only had the right of feudal tenure. Sovereignty of New Guinea rested with the Dutch East India government who could take over its management in full or in part at its own discretion.26

In 1875 the eastern border of the territory was marked and this extended the land area previously proclaimed in 1828. The Dutch Government Almanac of 1875 outlines the Dutch area of New Guinea as extending from Cape Bonpland (the eastern side of Humboldt Bay) at 140°47' east longitude on the north coast until 141° east longitude on the south coast, including the adjoining islands (Figure 23 bottom). This border apart from small changes became the boundary of Dutch New Guinea. Subsequently the north coast border was extended to 141° east longitude and the south coast one to 141°01' at the mouth of the Bensbach River.27 The river was named after the plume trader who became the Resident of Ternate, J. Bensbach, at the suggestion of the Administrator of British New Guinea, Sir William MacGregor.28

Local leaders continued to make stands against foreign influences. On Halmahera in 1875–76 the so-called ‘Prophet of Kau’ led a movement against the Sultans of Ternate and Tidore. His cult attracted some 30,000 followers.29 Likewise in 1894 a konor raised himself on Roon Island and terrorised the western part of Cendrawasih Bay. These activities declined as the Dutch presence increased. A Dutch government post was established in Cendrawasih Bay at Manokwari in 1898 (Figure 23 bottom).

The Tidorese throne became vacant in 1905 and the lack of a ruler diminished its autonomy. In 1907 the Dutch colonial government forced Ternate to relinquish its authority over east Sulawesi, as well as Banggai and other islands. The Dutch also forced the government of Tidore to sign away its independence in 1909.30 In 1910 Ternate and Bacan signed agreements which invalidated all their old contracts with the Dutch, incorporating them more within the colonial state. In 1914 120Sultan Usman of Ternate was banished to Java following a tax revolt in Jailolo. This led to further modifications as to the degree of autonomy Ternate was permitted within the colonial state. The next seven chapters are concerned with specific areas of New Guinea.31

Notes

1. van Fraassen 1981: 11–12; Wright 1958: 12.

2. Galis 1953–4: 17.

3. ibid.

4. ibid.

5. Haga 1884 cited by Galis 1953–4: 17.

6. Leupe 1875 cited by Galis 1953–4: 17.

7. Galis 1953–4: 17–8.

8. Ambergris is a waxy substance produced by the intestines of sperm whales. It is found floating in the sea or washed up on the shore. It is used in perfumes, as a fixative and formerly in cookery.

9. Forrest 1969: 106.

10. Forrest 1969: 101–2.

11. Galis 1953–4: 37.

12. Galis 1953–4: 19: Kamma 1972: 217.

13. van Fraassen 1981: 12, 20.

14. Galis 1953–4: 20; van der Veur 1966a: 8. Some of the islands cited could not be located.

15. Robide van der Aa 1879 cited by Galis 1953–4: 20.

16. van Fraassen 1981: 21–2.

17. Galis 1953–4: 21: van der Veur 1966a: 10–11; van der Veur 1966b: 2.

18. Haga 1884 cited by Galis 1953–4: 21.

19. Kops 1852.

20. Earl 1853: 86; Galis 1953–4: 22; Kops 1852: 335.

21. Dumont d’Urville 1834.

22. Earl 1853: 82–3; Kops 1852: 315.

23. Wallace 1986: 312, 314, 496.

24. Rowley 1966: 58.

25. van Fraassen 1981: 21–1.

26. Galis 1953–4: 48

27. ibid; Prescott et al 1977: 84–5: van der Veur 1966a: 64–5.

28. van der Veur 1966a: 64–5.

29. Muller 1990b: 56.

30. Tidore retained some jurisdiction in New Guinea, as further legislation had to be enacted in 1911 to ensure that areas formerly under Tidore were subjected to the 1909 bird of paradise hunting legislation (Wichmann 1917: 388; Staatsblad van Nederlandsch-lndie 1909, No. 497; Staatsblad van Nederlandsch-lndie 1911, No. 473).

31. van Fraassen 1981: 21–2.