12

Plumes fund economic development

in Kaiser Wilhelmsland

Indonesian presence

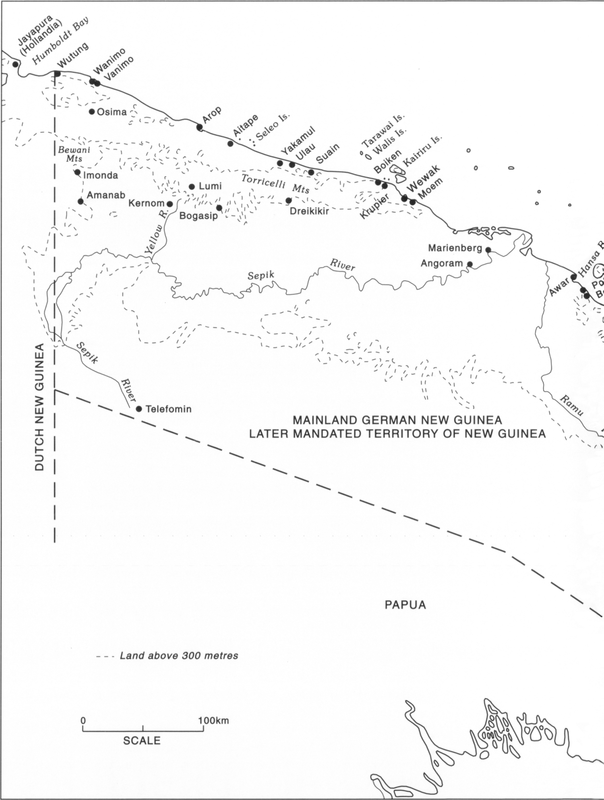

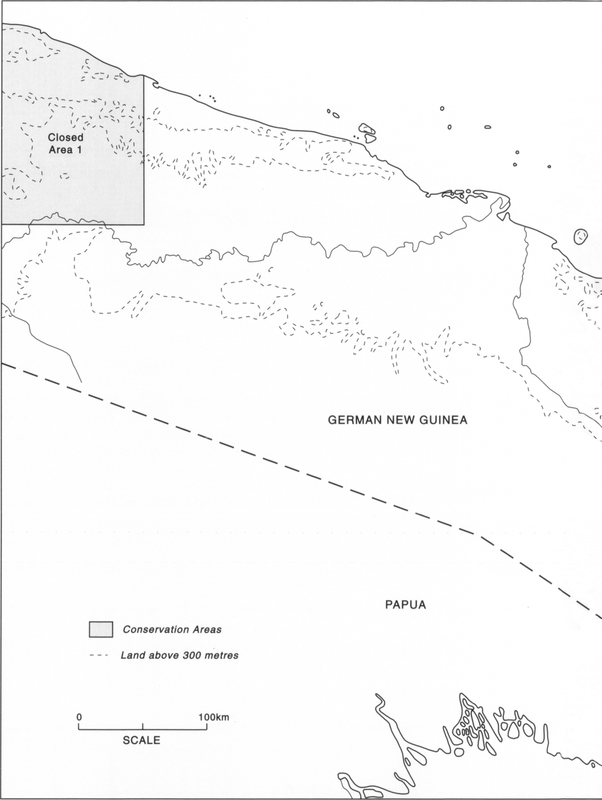

Indonesian and Chinese traders from Ternate began to trade eastwards along the north coast in the latter half of the nineteenth century.1 By the early 1880s they were active as far east as the Tarawai and Walis Islands off the Sepik coast of northern New Guinea (Figure 48). Some Sepiks travelled to the Moluccas with these traders. Richard Parkinson reports in 1900 that he met three Tarawai Islanders who had been to Ternate, when he visited Tarawai and Walis.2 As a result of this contact certain Malay words such as tuan (master) and kiappa3 (coconut) became known on the Sepik coast.

The people on Kairiru Island in the East Sepik claim that iron tools were first introduced to their island by a Chinese trader living on Tarawai Island. Their forbears exchanged taro and bananas for axes and knives with this trader, whom they called Ternate.4 This trader probably visited the volcanic island of Kairiru for food, whilst his commercial interest was centred on the trepang and green snails found off the coral islands of Tarawai and Walis.

The German New Guinea Company did not initially see these Indonesian and Chinese traders as a threat to their economic interests. At first its directors were more concerned with establishing large plantations than engaging in barter trade with New Guineans. This policy changed in 1897. By then the Company directors had come to realise that crops such as cocoa, coffee and tobacco were not viable plantation crops on the north coast of New Guinea. The Company then began to establish coconut plantations and to engage in barter trade with New Guineans. The first Company trading posts were established in 1897 and it soon became apparent that greater profits would be made if they did not have to compete with Indonesian and Chinese traders operating out of Dutch New Guinea. In 1904 Governor Hahl of German New Guinea sought Dutch 220assistance to prohibit the entry of Indonesian and Chinese bird of paradise hunters from Hollandia and Ternate on the basis that they were causing unrest in German New Guinea. By the end of the decade Indonesian and Chinese hunters operating out of Dutch New Guinea had ceased plying their praus along the coast of German New Guinea. Some however continued to operate in the vicinity of the border.5, 6

The border crossing prohibition was successful on the coast, but not inland where it could not be enforced. The Dutch agreed that certain measures should be taken to control illegal inland boundary crossings, but little was achieved as there was no active supervision on the German side.7

Indonesian hunters and traders usually returned to the same areas year after year. They tended to stay in one locality for a while, perhaps a month, and traded goods such as beads, tobacco, knives and cloth for bird skins hunted by the local people. In 1910 Leonhard Schultz-Jena observed Indonesian bird hunters providing local men with guns to shoot birds for them.8 Some hunted birds themselves. The good relationship these hunters seem to have had with many inland groups suggests that they paid villagers for the right to hunt on their land. Indonesian hunters in the Amanab area used muzzle loading muskets. The old men relate that if the hunters ran out of shot they used pebbles and powder instead.9 The people in the Waina-Sowanda area south of Imonda also describe flintlock muskets.10

When the Indonesian hunters and traders penetrated the interior, they kept to certain defined trade routes, which, although no more than bush tracks, were recognised by local groups as lawful thoroughfares for Indonesian bird hunters and the New Guineans employed by them. As long as they were traders, they passed through the most aggressive tribes without fear, for their lives were sacred while they remained on these tracks.11

At Krisa village, some 20 kilometres inland from Vanimo in the West Sepik, an old man told Evelyn Cheesman12 in the 1930s, through an interpreter, about the Indonesian bird hunters and traders who had come to his village.

He was delighted to talk about the traders who came no more, only his generation remembers them. They were trading of course in paradise birds. One man came every year and stopped for a month at a time, while the villagers hunted birds for him and he paid in beads, knives, cloth, cowrie shells, tobacco – things that would cost a few shillings. I learnt that this was a regular trade route leading inland, and this same trader went beyond the Bewani Mountains. I asked whether the villagers liked the traders. The old man beamed, there was 221no doubt about his feelings: “Abidi wai-ai!” (traders good), he repeated several times. The old trading road crossed the plain to the Bewani Mountains and beyond them to country inhabited by the Bendi tribe …13

The high market prices resulting from the European plume boom after 1908 would have encouraged Indonesian hunters and traders to expand their operations further into the sparsely populated interior of what is now the West Sepik (Sandaun) province. The hunters were attracted by the large numbers of birds of paradise that could be found there.14

Many Indonesian bird hunters got on well with the local people. One recorded exception concerns a complaint made by Wanimo villagers to Governor Hahl about bird hunters who supported one village against another during a local dispute.15

Sepiks employed by Indonesian hunters sometimes kept some of the birds shot on hunting expeditions. On one occasion, a Wanimo youth working for two Indonesian hunters in the Osima and Bewani areas of the West Sepik managed to keep the best of his catch. He was one of five youths employed by these hunters. They had been told to use their catapults and try and shoot 24 birds each before coming back to camp. This youth shot only 11 birds and four of these were fine specimens. After hiding the best in the bark of a tree, he returned to the camp and gave the Indonesians the other seven birds. He then got leave to visit a relative in a nearby village. The four birds were given to the relative living in this village to prepare and keep safe until he could return to collect them. The skins were later used in his niece’s marriage ceremony.16

The first Australian patrol officers to enter the Amanab-Lumi area were surprised to learn that they were not the first foreign visitors to these parts. In the 1920s to early 1930s Australian government patrols in the Vanimo hinterland crossed the tracks of Indonesian hunters from over the border.17

As we have seen in Chapter 11, Hollandia in Humboldt Bay was one of the main centres in Dutch New Guinea exporting bird of paradise skins. It also became an outlet for plumes smuggled out of the Mandated Territory of New Guinea, as from 1920 all plume exports were restricted and registered. They were finally prohibited early in 1922. In 1921 the Australian patrol officer based at Aitape had his carriers help the Vanimo patrol officer carry certain boxes, which had to be kept dry, some 25 kilometres from Aitape to Arop. Twelve months later the Aitape officer learnt that he had assisted in carrying 300 contraband bird of paradise skins destined for Hollandia.18 The Vanimo officer involved was dismissed.19222

Figure 48: Mainland German New Guinea (Kaiser Wilhelmsland), later the Mandated Territory of New Guinea.223

224E.D. Robinson in 1934–5 reports in his patrol report20 that while at Kernom (Kernam) on the Yellow River, he learnt through his corporal, who was able to talk to a local in pidgin Malay, that two Indonesians and a party of New Guineans had been in the vicinity shooting birds of paradise about five months previously. Although contraband hunting continued, the amount of trade going through Hollandia quickly declined once commercial hunting was prohibited in much of Dutch New Guinea in 1924,21 though hunting was allowed to continue in the Hollandia region until 1931.22 Once European markets were closed, Asian demands continued. The Indonesian hunters reported by Robinson would have been supplying this old market which still continues in Indonesia in the 1990s.

German presence

By the middle of the nineteenth century, Britain, France, the Netherlands, Portugal and Spain had raised their flags and established settlements on most of the islands of Southeast Asia and the Pacific. They colonised all the islands that gave the appearance of having an economic potential. New Guinea was largely ignored. Some enthusiastic mariners had claimed it for their homelands,23 but no nation was willing to bring any of these claims into reality by maintaining an interest on the island.

Although the Dutch did annex the western half of New Guinea in 1828, they did not colonise their claim. At that time the Dutch were not interested in New Guinea’s resources; they merely wanted to keep other countries from the eastern flanks of the Dutch East Indies. They avoided the problem of administrating an unprofitable colony by championing the rights of the Sultan of Tidore to be the overlord over their annexed territory (see Chapter 6).

In the early 1880s, the president of one of the largest private banks in Berlin, Adolph von Hansemann, began to promote New Guinea to his countrymen as a profitable investment area. He was so convinced of its potential that he established a group of German financiers to acquire land on the New Guinea mainland in 1884. On behalf of this group Otto Finsch and Captain Dallman travelled to New Guinea and acquired land rights from the local inhabitants in 1884–5. When the required land rights had been obtained, the German financiers persuaded their government to claim northeast New Guinea as a colony. This took place in 1884. In the same year Britain was persuaded to annex territory in New Guinea on behalf of the Australian colonies. These claims led to the division of eastern New Guinea into two parts in 1885, the northern becoming German, the southern British.24 In 1895 the southern border was adjusted to the 225natural boundary of the Bensbach River mouth between Dutch and British New Guinea (Figure 38).25

The German Chancellor, Count Otto von Bismarck, was willing to acquire new colonies,26 but was reluctant to invest large sums of government money in their administration. This problem was overcome by making chartered companies, which were modelled on the former East India Companies, responsible for the administration of new colonies. For undertaking this responsibility these companies received economic concessions from their home government. In 1885 the German financiers obtained a charter from Bismarck to establish the New Guinea Company (Neu Guinea Kompagnie). This charter allowed the New Guinea Company to administer and acquire land in German New Guinea, but the German government reserved the rights over foreign relations and justice.27

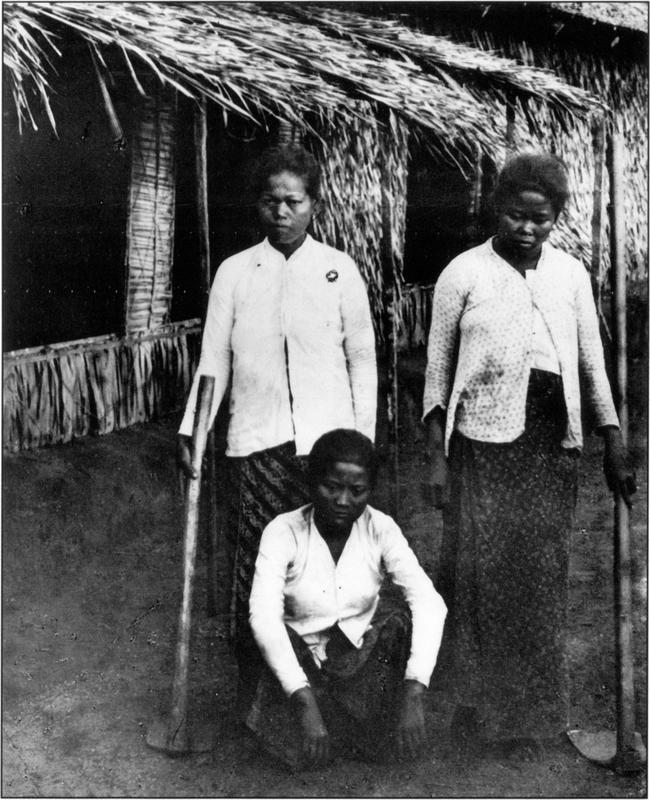

Von Hansemann and his associate directors thought northeast New Guinea was a fertile land where they could quickly establish successful cocoa, coffee and tobacco plantations. In less than two years after obtaining its charter the New Guinea Company had spent two and a half million marks (about £125,000) on shipping, staff and supplies in German New Guinea. Unsuitable soils and climate, as well as disease, labour and shipping problems brought about these high costs. By 1890 scientific surveys funded by the Company had established that there appeared to be no rich faunal, floral or mineral resources available for exploitation. Nevertheless the Company persevered and established four tobacco plantations near Stephansort (Bogadjim) in Astrolabe Bay in 1892. Javanese and Chinese labourers were recruited from Java and Singapore to work in these plantations (Plate 37). Although the tobacco leaf sold well in European markets, the plantations were not a financial success.

By 1897 the tobacco, cocoa and coffee ventures were acknowledged failures. From this time the German New Guinea Company concentrated on trading for village copra and establishing coconut plantations. Six trading stations were established. One was on Seleo Island off Aitape. Herr Lücker was the manager, assisted by Diack. They traded in copra, trepang, turtle shell and pearl shell. Five other trading stations manned by Chinese or Indonesians were established on the mainland and neighbouring islands. The Chinese and Indonesians running these trading posts did not receive regular wages. At first they were only repaid the cost of the products they purchased and given provisions. They received a profit margin once they had sold the goods allocated to them.28

In 1898 Lücker established a trading station at Arop on the eastern side of the Sissano Lagoon. It was staffed by an Indonesian trader 226called Kromo, two Chinese and four New Guinean assistants.29 Apart from trading in the limited supplies of trade copra, the staff of this trading station, as well as others further east along the Aitape coast, investigated the inland mountains for birds of paradise.

In 1897 the Company began to establish coconut plantations at Berlinhafen near Aitape and on the Gazelle Peninsula of New Britain in the Bismarck Archipelago.30 In 1898 the Company’s exports were worth 115,400 marks (£5,770). This was a poor return on a total investment of eleven million marks (£550,000) over 14 years. Financial difficulties led the imperial government to relieve the New Guinea Company of its administrative responsibilities in 1899.

Plate 37: Three Indonesian women employed on one of the New Guinea Company’s tobacco plantations at Stephansort (Bogadjim) in the Madang area in 1897.

Photo: By Lajo Biro, courtesy of the Ethnographical Museum, Budapest, Hungary.

227Starting in 1899, the German government made annual compensatory payments of 400,000 marks to the Company in return for it relinquishing its administrative control over German New Guinea. Although no longer administrating the colony, the Company continued to dominate its economy. In 1914 one-third of all German planters and traders worked for the Company and it owned half the alienated land in the colony. Its plantations were located in New Ireland, the Duke of York Islands and New Britain (Gazelle Peninsula and Witu Islands) in the Bismarck Archipelago and the north coast of mainland New Guinea. By 1914 in terms of its capital value it was the largest plantation company in any German colony.31

The impact of early European contact in German New Guinea

Most people in mainland German New Guinea had experienced little direct contact with Europeans prior to annexation, but a number of local interactions had occurred. Artifacts and historical records indicate that these involved European sailors at Budup in Madang, Dutch sailors at Arop in West Sepik and a Russian scientist on the Rai Coast of what is now the Madang Province. The Budup incident became incorporated in the Kilibob and Manup origin myth of the Madang coast.32

The villagers living in the vicinity of the tobacco plantations established at Stephansort (Bogadjim) in Astrolabe Bay and those in contact with the trading stations established on the Sepik coast seem to have borne the brunt of the demoralisation that emerged in their societies when faced with the different technology and world view of the Germans. In 1891–3, when the tobacco plantations were being established, the Hungarian natural history and artifact collector Samuel Fenichel was able to collect cult objects for the Hungarian National Museum. A few years later in 1897, another Hungarian, Lajos Biro, was only able to collect everyday utensils, as cult objects no longer existed in Astrolabe Bay.33

Similar changes occurred on the Sepik coast. The German ethnographer Richard Parkinson first visited what is now the Wewak-Aitape coast in 1893. He was astonished and dismayed to find on a subsequent visit in 1898–9 that it was now difficult to acquire artifacts which had been easy to acquire only five years earlier. However, the presence of European traders and the Catholic Mission had brought one change which was to the ethnographer’s advantage. No longer was sign language the only means of communication. It was now possible to communicate with the local people through interpreters who had worked for the traders or the mission.34228

Copra

By the 1850s a market had developed for coconut oil in Europe. In the 1870s it was replaced by a growing demand for copra.35 When the Lever Brothers discovered that copra could be used instead of tallow in soap manufacturing in 1885, not only was Sunlight soap born, but also the parent firm of Unilever. This new demand for copra led to increased trading for village copra and subsequently to the establishment of coconut plantations in many parts of the world.

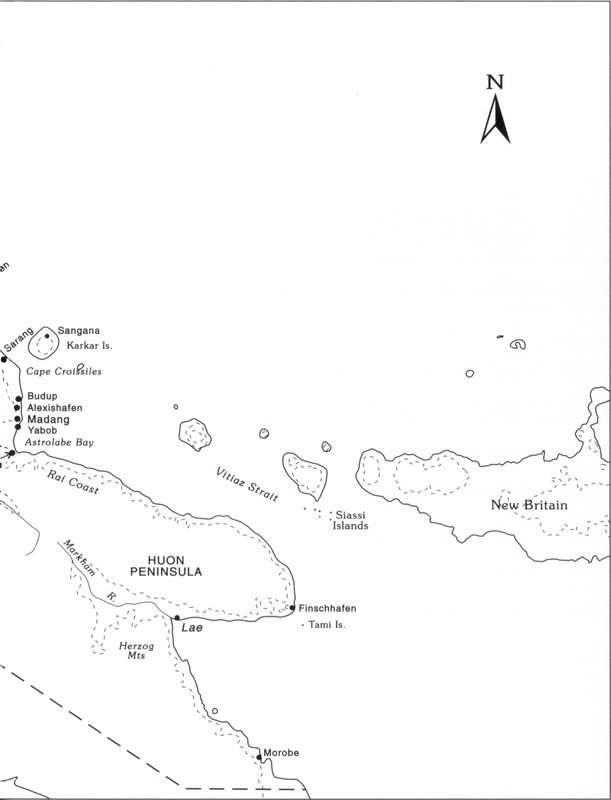

Coconuts grow well in New Guinea. Despite an antiquity of the palm of over 5,000 years on the north coast, culturally induced scarcities were the norm on this coast and in other parts of New Guinea in the 1880s.36 With the exception of the Aitape area, villages on the north coast of German New Guinea did not have large stands of village coconuts. They were rare and highly valued.37 The Siassi and Tami islanders of Vitiaz Strait and the Huon Gulf were observed to grow more coconuts than the people on the mainland, but in order to maintain their monopoly, the Tami broke the nuts before trading them. This induced scarcity seems typical of the north coast. Ber, an elder of Yabob village near Madang who was born in 1904, could remember when Rai Coast villages had very small stands of coconuts.38

In other parts of New Guinea villagers had large stands of coconuts. They were able to supply copra to barter traders. This was the case in the New Guinea Islands villages, especially those in East New Britain and New Ireland. The availability of village copra led to the establishment of trading posts. The first trading post to be established in what is now Papua New Guinea was in the Duke of York Islands in East New Britain in 1872.39

In the New Guinea Islands, trade copra was the usual source of funds by which plantations were established. By contrast Kaiser Wilhelmsland (mainland New Guinea) settlers were unable to raise capital in this way. The growing demand for bird of paradise plumes in Europe which became a boom industry in 1908 provided an alternative source of income.

Bird hunting before the plume boom

Before 1908 birds of paradise were shot in German New Guinea, as in British and Dutch New Guinea, to supply both natural history collectors and the growing plume market. There was probably an upsurge in this activity when Carl Hunstein joined the New Guinea Company in 1885. He had previously worked in British New Guinea as a bird collector and continued to do so in German New Guinea (see Chapter 4).

229Most of the reports of bird hunting in German New Guinea before the plume boom of 1908 concern either the New Guinea Company’s first administrative centre at Finschhafen, the tobacco plantations established near Stephansort (Bogadjim) in Astrolabe Bay in 1891–2 or scientific expeditions.

From the beginning the German administration took steps to protect the birds from extinction. For instance, on the 18th of July 1887 the administrator introduced a police regulation that prohibited the hunting of either moulting male or female birds of paradise in the Finschhafen district.40

In 1891, some seven years after the annexation of Kaiser Wilhelmsland, an ordinance was passed requiring bird of paradise hunters to have a licence.

Apart from controlling the use of firearms by non-Europeans, this legislation was considered overdue at the time as many New Guinea Company staff were not obtaining permission before using their company’s boats and employees to hunt the birds.41 By 1891 there were two full-time European bird hunters, German brothers by the name of Geissler, working in the Astrolabe Bay and Huon Peninsula area of Kaiser Wilhelmsland (Figure 48). They spent long periods out hunting, but were not considered to be making a profit.

By mid 1892, fourteen individuals had applied for three-month licences and paid the fee of 20 marks. Only two individuals, Geissler and Grubauer, had paid 100 marks for six-month licences. The introduction of licences had the effect of encouraging more hunting than previously, as holders attempted to recoup the cost of their licences and make a profit from their activity. This increase in hunting from 1891–2 was especially noticeable in the Astrolabe Bay area.42 As mentioned above, this was when the tobacco plantations were established near Stephansort.

The plume boom of 1908

There was little further growth in the number of licences after 1891 until the bird of paradise plume boom of 1908. In 1891 bird of paradise skins fetched 8–12 marks (about 7–11 shillings) in German New Guinea. After 1908 they were worth three to four times as much. This price rise encouraged more hunting. This is evident from the revenue the administration obtained from hunting licences. In 1891 it was 480 marks; just prior to the plume boom of 1908 it became 600 marks. By 1909 the administration of German New Guinea was receiving 20,000 marks in revenue from licences.43

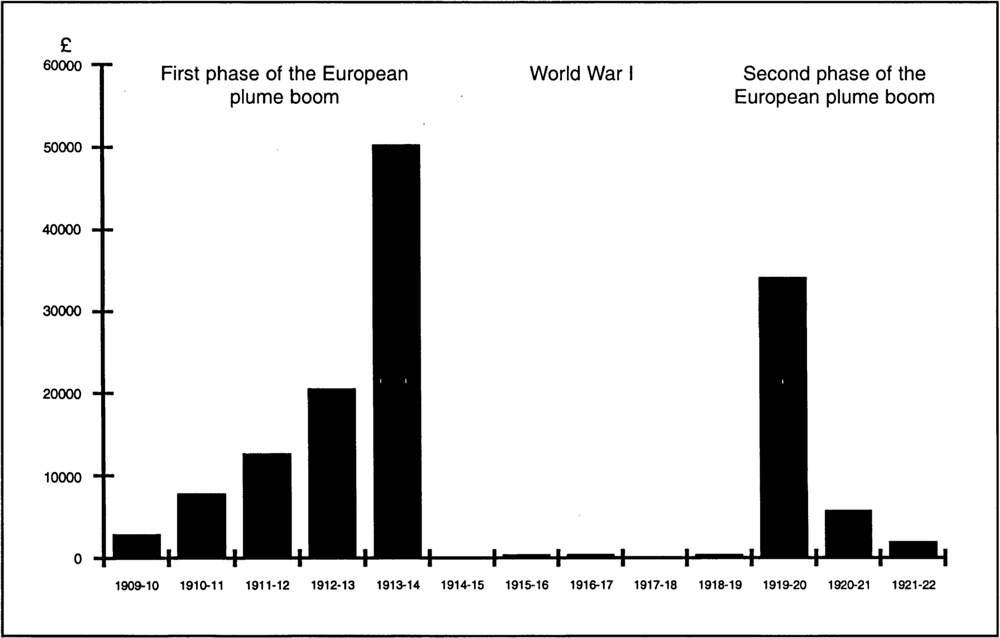

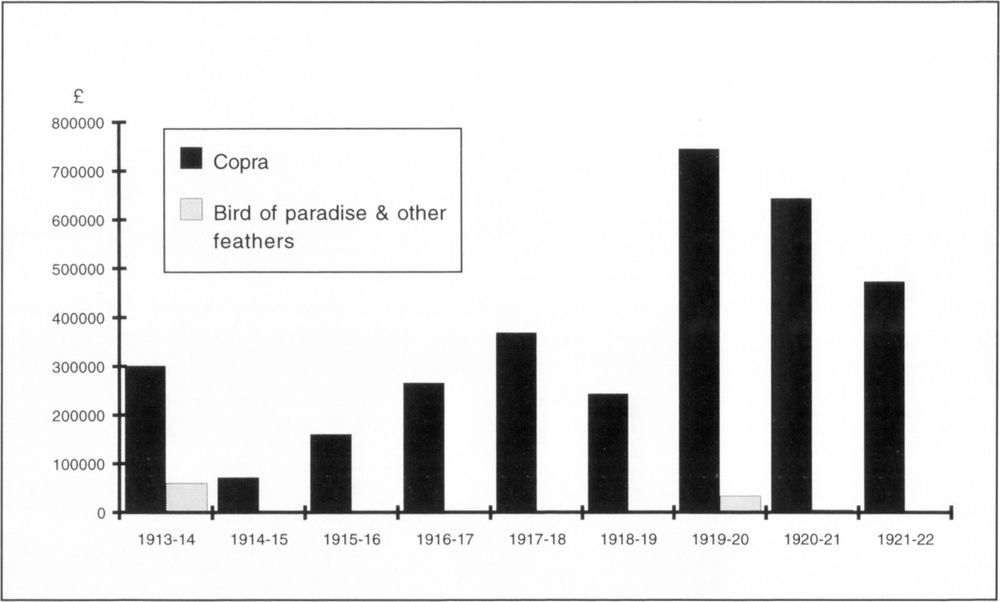

The impact of the European plume boom was felt in both German New Guinea and Papua by late 1908. While the Papuan administration 230took steps to prohibit the commercial hunting of these birds, the German administration was allocating exported bird of paradise skins a separate entry within the colony’s statistics. Until 1909 the number of bird of paradise skins exported had been insufficient to warrant such recognition; they had just been grouped with other small-scale income earners,44 see Table 13 and Figure 49.

Table 13: The number of bird of paradise skins exported from German New Guinea and the Mandated Territory of New Guinea between 1909–22 and their value.

| Year | Number exported | Value (in marks) | Value (in pounds)a | Export Duty (in marks) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1909–10 | 3,200 | 65,000 | 2,979 | 4,400 |

| 1910–11 | 5,706 | 171,000 | 7,838 | 11,412 |

| 1911–12 | 8,779 | 278,000 | 12,742 | 43,900 |

| 1912–13 | 9,837 | 449,260 | 20,591 | 49,190 |

| 1913–14 | 16,691 | 1,096,961 | 50,277 | 83,455 |

| Commencement of World War I | ||||

| 1914–15 | ||||

| 1915–16 | 98 | |||

| 1916–17 | 125 | |||

| 1917–18 | ||||

| 1918–19 | 100 | |||

| 1919–20 | 34,133 | |||

| 1920–21 | 5,812 | |||

| 1921–22 | 2027 | |||

Notes:

1. The New Guinea (Rabaul) Gazette (1916: 44) gives the conversion rate of one German mark to 11 English or Australian pence. For those not familiar with pounds, shillings and pence, there were 20 shillings in a pound, and 12 pence in a shilling.

2. The period from 1915–22 includes other feathers.

Sources: Sack and Clark (1979: 315, 316, 330, 331, 348, 368).

Sack and Clark (1980: 156).

Government Gazette, Territory of New Guinea 1913–14, Appendix A.

Government Gazettes, Territory of New Guinea 1916–22. (There are some discrepancies in the figures given in the 1914–21 and 1921–2 reports to the League of Nations in the New Guinea Government Gazettes).

231From the beginning Governor Hahl proposed that the plume boom should be managed in such a way that the birds were harvested and not depleted, with the profits contributing to the cost of developing and administering German New Guinea. His management policy was to harvest the birds without exterminating them, until fashions changed. The value of plumes would then decline on the world market, hunting would cease and the birds would be able to recolonize depleted areas.

Over the years the legislation controlling commercial bird of paradise hunting in Kaiser Wilhelmsland was amended and new regulations and requirements introduced. This legislation was concerned with hunting licences, export duties, closed seasons and conservation areas.

Figure 49: The value of bird of paradise skins exported from German New Guinea and the Mandated Territory of New Guinea from 1909–22.

Notes:

1. The period 1914–22 includes other feathers.

2. Inflation does not play a part in explaining the large increase from 1909-1914, as prices remained stable in Germany between 1890–1916. For instance, a domestic letter cost the same price (10 pfenning or 10 parts of a mark) to post throughout this period ( J. Tschauder personal communication 1991).

Source: Based on Table 13.

232Measures taken by the German administration to ensure the survival of birds of paradise in German New Guinea

1. Licensees had to invest their profits in development projects within the colony

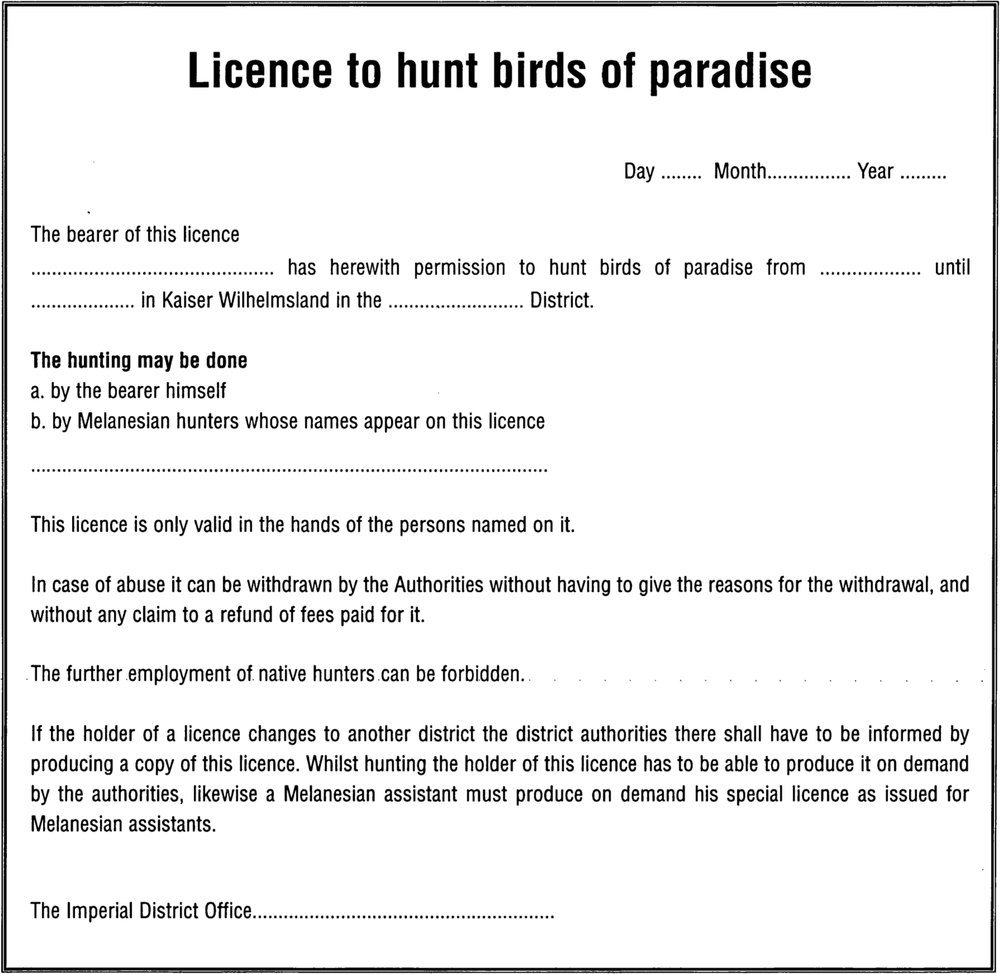

After 1908, a hunting licence was only issued by district officers to those who agreed to invest the profits they made in development projects within the colony.45 Once the ‘plume fever’ started, the cost of an annual hunting licence rose in accordance with the world price for plumes. A licensee could shoot any number of birds. However, if requested to do so, he was obliged to give a report at the end of each year which detailed how many assistant hunters and carriers he employed, where he hunted and how many birds had been shot according to species and what was the sum total of his profit.46

Table 14 details the changing cost of licences and the conditions imposed on the licensees.

Table 14: Summary of the main bird-hunting licence legislation in German New Guinea.

| 11 Nov. 1891 | Ordinance regarding hunting birds of paradise Licence now required, fee 20 marks, fine for hunting without a licence 1,000 marks or one month in gaol |

| 27 Dec. 1892 | Ordinance regarding hunting birds of paradise Licence must indicate number of assistants employed and area where hunting, fee for one year is 100 marks or a short-term licence is 20 marks |

| 13 March 1907 | Ordinance of 1892 amended, increasing fees fee for one year 160 marks fee for 6 months 90 marks fee for 3 months 50 marks |

| 18 March 1911 | Ordinance Licences now issued at district office at Friedrich Wilhelmshafen (Madang) and sub-district offices at Eitape (Aitape) and Morobe. The content of this licence is given below. Licences for non-indigenous people (e.g. Chinese) require them to hunt in a stipulated area; they cannot employ New Guinean hunters, unlike Europeans. The licence holder has to personally supervise his assistant hunters or authorise another European to supervise them on his behalf. To have more than two New Guinean hunters 233the licence holder has to be both a resident and businessman in German New Guinea, for example running a tradestore or establishing a plantation. |

Fees are now as follows:

| months | number of Melanesian hunters | cost in marks |

|---|---|---|

| 3 | 1 or none | 20 |

| 3 | 2 | 125 |

| 6 | 1 or none | 150 |

| 6 | 2 | 200 |

| 12 | 1 or none | 200 |

| 12 | 2 | 300 |

There was a limit of six New Guinean hunters for any one venture.

1913 Ordinance

From this date, for security reasons, New Guinean hunters are only allowed to use muzzle-loaders and are not allowed to hunt in the immediate neighbourhood of their own villages.

Licences are now required for all birds with decorative plumage with trade value.

Licence fees are now as follows:

| number of New Guinean hunters | cost in marks |

|---|---|

| 1 or none | 200 |

| 2 | 300 |

| 3 | 400 |

Hunters are required to provide on request the following information: number of assistants, number of muzzle and breech-loaders used, number of permanent workers (carriers), area(s) where hunted, number of birds shot according to species and profit made.

Sources: Ordinances of 1891, 1892, 1907, 1911 and 1913.

234The content of the bird of paradise hunting licence as issued on the 18th of March 1911 is given in Figure 50:

Figure 50: Text of licence to hunt birds of paradise.

Source: Hahl 1911.

2352. Export Duty

The German New Guinea government not only obtained revenue from bird hunting by charging licence fees; they also imposed an export duty (Table 15). It was first introduced for bird of paradise skins on 10 June 1908 and was increased to 2 marks per skin in 1910.47 The rate varied according to species and increased in accordance with the world prices for skins. In 1911 the export duty on recognised commercial skins rose from 2 to 5 marks as a means of raising more revenue for the administration, rather than increasing licence fees.48 In November 1912 the Colonial Office in Berlin requested that the export duty be raised from 5 to 20 marks.49 Governor Hahl50 thought this unreasonable and complained unsuccessfully about the extent of the requested rise. In 1914 it became 20 marks.51

Table 15: Summary of the export duties on bird of paradise skins in German New Guinea.

| 1908 10 June | introduced on bird of paradise skins (rate not stipulated) |

| 1910 21 Sept. | raised to 2 marks per skin |

| 1911 | raised to 5 marks per skin |

| 1914 | raised to 20 marks per skin |

A different rate was charged for rarer species shot by natural history collectors, as it was thought that if a higher duty was imposed on rare species, it would make them less attractive to commercial hunters.

The market demand for new types of plumes and the increasing prices being offered saw goura (crowned) pigeon feathers listed for the first time as an export commodity in 1911–1252 and cassowary and egret feathers were mentioned for the first time in 1913–14.53 Export duties were also levied on these species. In October 1913 the export duty on goura pigeons was increased from half a mark to 5 marks.54 Whilst goura pigeons first appear in official statistics for German New Guinea from 1911–12, they had been exported from Dutch New Guinea for some time as they are mentioned in fashion magazines from the 1890s.55

Although some bird of paradise skins may have been smuggled across the border into Dutch New Guinea to avoid paying customs duty, the bulk of the skins shot in German New Guinea were shipped to either Singapore or Hong Kong by the North German Lloyd Line, and thence to their overseas markets. The service from Singapore visited Friedrich Wilhelmshafen (Madang) or Stephansort (Bogadjim) four times a year.56236

3. Closed seasons

The administration of German New Guinea also declared closed seasons as an additional way of protecting the birds; see Table 16. In 1911 a closed season was declared from the 1st of February to the 30th of April. During this time it was illegal to hunt birds of paradise.57 In 1912–13 the hunting season was made even shorter, and hunting was made illegal between the 1st of November and the 15th of May.58 In December 1913 the same closed season was declared for goura pigeons and cassowaries as for birds of paradise.59

These closed seasons were declared in an attempt to satisfy the conservationists; they had little impact on hunting practices, as most of the favoured birds were not in full plumage during the closed period. From late 1912 the Colonial Office considered a proposal to ban bird of paradise hunting for eighteen months beginning the 1 April 1914.60 A closed season of this duration was then demanded by the Colonial Office. The German Ornithological Society did not think this was long enough and suggested a ten-year ban. This request was rejected by the German Colonial Committee for the Protection and Commercial Use of Birds, as it considered the eighteen-month ban met the immediate demands of the Society.61 It was finally decided to enforce a one year ban from the 1st of April 1914. On the 28th of June 1914 the assassination of Archduke Franz-Ferdinand set in train a series of events in Europe leading to the outbreak of the First World War in August. By September 1914 German New Guinea had been occupied by Australian Forces, whose record in regard to bird of paradise hunting and conservation will be described below.

Table 16: Summary of the closed seasons for birds of paradise, goura pigeons and cassowaries in German New Guinea.

| February 1 - April 30 (3 months) declared 18 March 1911 for birds of paradise |

| November 1 - May 15 (6½ months) declared 1913 (also goura pigeons and cassowaries) |

| Total ban from 1 April 1914 for 18 months is proposed for consideration in late 1912; a one-year ban was imposed from 1 April 1914 |

These closed seasons, as in Dutch New Guinea, centred on those months when the birds were not in full plumage and hunting would not have been profitable. Nevertheless there were some in German New Guinea who considered a closed season of six and a half months as 237having a crippling effect on development. In their view this placed the owners of many small ventures in a difficult position, as even in 1913 there was still little trade copra available on the north coast.62

4. Conservation areas

In 1910 consideration was given to establishing reserves for rare and uncommon species to prevent their extinction, but this was not considered a priority as hunters were only operating in the coastal regions of Kaiser Wilhelmsland.63 This it was believed left the birds free to retreat into the inaccessible mountains of the coastal hinterland.64 This misconception was abandoned as more information about the distribution and habitats of different species became available.

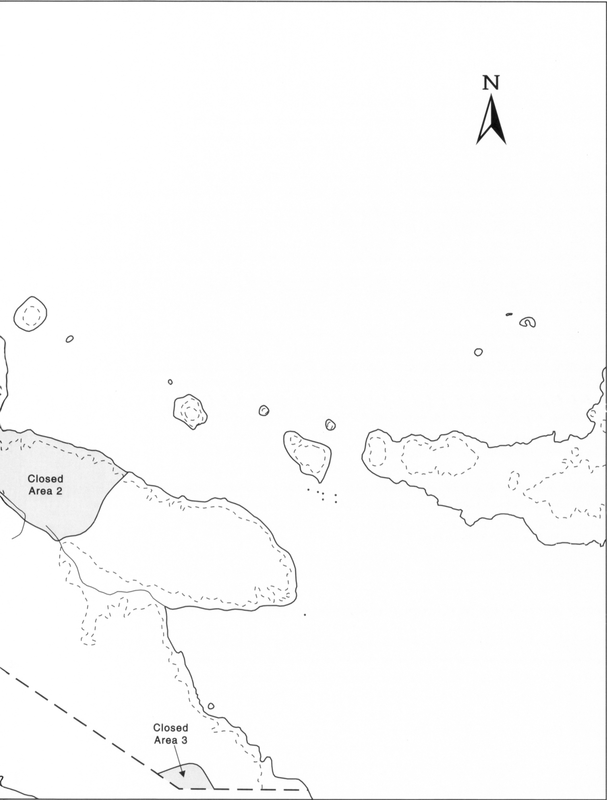

There was also a demand for further protective measures from various outside agencies. In line with the international nature protection movement of the period, the creation of nature reserves in German colonies followed a resolution of the Plenary Session of the German Colonial Society at Stuttgart on 9 June 1911. It was proposed that in these reserves flora and fauna would be preserved and protected as in Yellowstone Park. The overall aim was to preserve the designated areas in their untouched condition for generations to come.65 In 1912 the governor of German New Guinea declared three areas as wildlife protection areas;66 see Table 17 and Figure 51.

Table 17: Wildlife protection areas (National Parks) in Kaiser Wilhelmsland

In 1912 three areas were declared out of bounds to bird of paradise hunters (Sack and Clark 1979: 366).

| Closed Area 1 | protected the Yellow Bird of Paradise (Lesser Bird of Paradise, Paradisaea minor). It was well known that this area was heavily hunted by Indonesian hunters. |

| Closed Area 2 | protected the Yellow Bird of Paradise (Lesser Bird of Paradise, Paradisaea minor) and White Bird of Paradise (Emperor Bird of Paradise, Paradisaea guilielmi). |

| Closed Area 3 | protected the habitat of the Blue (Paradisaea rudolphi) and Raggiana (Paradisaea raggiana) Birds of Paradise. |

Source: (Hahl 1913a: 190–3).238

Figure 51: The conservation areas declared in Kaiser Wilhelmsland in 1912.239

240It was recognised that the areas set aside as wildlife protection areas in German New Guinea had to be chosen in such a way that their existence would not interfere with current economic interests nor jeopardise the colony’s future development. Doubt was expressed about the administration’s ability to declare nature reserves in perpetuity when little was known about the resources of the areas concerned. There seemed little advantage in declaring an area protected if it was later allowed to be exploited because rich resources were subsequently found to be present.67

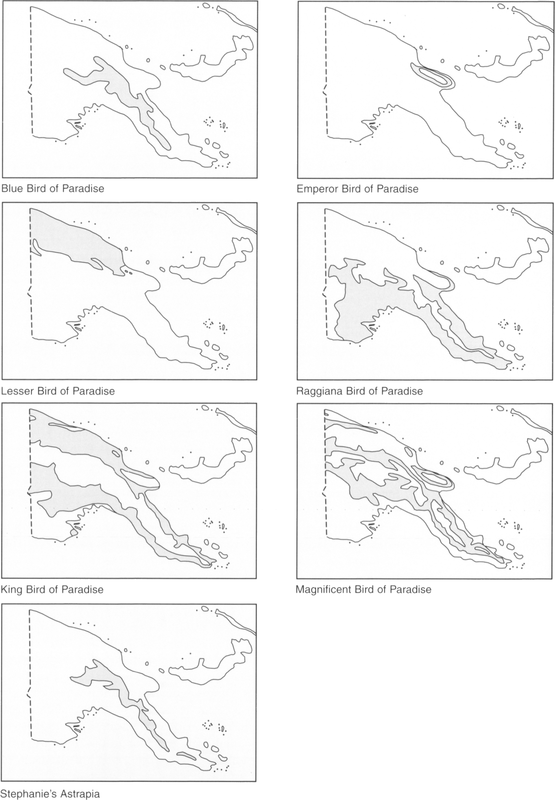

The main bird of paradise species hunted in German New Guinea for the European plume trade were the Lesser Bird of Paradise, the Raggiana Bird of Paradise, Augusta Victoria, a subspecies of the latter, and the Emperor Bird of Paradise. Their gregarious display habits meant that the hunters could find large numbers of these birds together and get good returns for their time. Sometimes a hunter would find a dozen birds displaying together in a cluster of trees. Less important were the Blue, King and Magnificent Birds of Paradise and Stephanie’s Astrapia. These species are more difficult to hunt as they generally display alone.68

Skilled hunters learnt the habits of the birds they sought. Thomas Gilliard69 describes the technique used by Adolph Batze to hunt the King Bird of Paradise in the Markham River forests. Walking through the forest Batze would make a short, medium-strength, ascending whistle, followed by a rapid series of shorter, lower notes, every half a kilometre. He would then stop and listen. Batze’s call seemed to agitate King Birds of Paradise as any bird in the vicinity would invariably respond from his tall forest tree.

The natural distributions of the main species hunted in German New Guinea for the European plume trade are shown in Figure 52. The Lesser Bird of Paradise was obtained from an area extending from the Upper Ramu Valley in the east to the Dutch border in the west. Raggiana, including the Augusta Victoria subspecies, would have been shot in the Markham Valley, the southeast part of the Huon Peninsula and around Morobe Station. Most of the Blue Birds of Paradise were shot in the mountains behind Morobe, and others may have been taken in the mountains to the south of both the Ramu and Markham Rivers. The Emperor Bird of Paradise is restricted to the hills and mountains of the Huon Peninsula. The King is common in coastal lowlands and the Magnificent is found on lower mountain slopes. Most of the Stephanie’s Astrapia would have been shot in the mountains inland of Salamaua.

An examination of the locations of the three protection areas (Figure 51) suggests that they were chosen partly to protect the birds, but also 241to provide legislation against Indonesian plume hunters. Prior to 1912 area 1 was mainly visited by Indonesian bird of paradise hunters illegally crossing over from Dutch New Guinea, rather than hunters operating from within German New Guinea. The presence of these Indonesian hunters irritated the German administration, but they had insufficient resources to monitor and stop their illegal border crossings. Occasionally German patrols would catch Indonesian plume hunters operating across the border. One incident occurred near the border in 1912, the two men caught were set adrift in their canoe. When it was washed ashore sometime later at Wutung (Figure 48), it was evident that they had died from starvation.70

Area 2 is now known to be a marginal area for both the Lesser and Emperor Birds of Paradise which it was declared to protect. The Lesser is only found in the western and the Emperor only in the eastern parts of Area 2. Protecting species in marginal areas where they are vulnerable to overhunting is a good conservation strategy.71

Area 3 protected the Blue and Raggiana Birds of Paradise inland of Morobe Station. This too was probably a good conservation strategy.

Anyone caught hunting in these reserves faced a month in jail or a 1,000 mark fine. This measure was taken to ensure that all species would survive the period of commercial hunting. The official view of the administration in German New Guinea was that the danger would be over once fashions changed and the value of plumes subsequently declined on the world market.

Size of hunting parties and employment of assistant hunters and traders

In 1910 the Hernsheim Company in Hamburg requested permission to establish a large hunting company in German New Guinea. This company had been founded in 1872 when the Hernsheim brothers became the first copra traders in the New Guinea Islands. Despite the company’s long history in German New Guinea, the Hernsheim proposal was turned down by the administration.

The proposal outlined an efficient hunting venture that would shoot large numbers of birds and thus be extremely profitable. The company wanted to employ 10 New Guinean hunters who together would shoot some 1,000 birds each year. W.J. Hahn of Hatzfeldthafen Plantation was to supervise operations.72 It was estimated that this would earn the administration 2,000 marks from licences and 2,000 marks from export duty. Governor Hahl rejected their application as he believed that large-scale ventures would soon exterminate the birds from the areas where they were allowed to operate. For this reason all entrepreneurs were restricted to a limited number of hunters.242

Figure 52: The natural distribution of the Blue, Emperor, King, Lesser, Magnificent and Raggiana Birds of Paradise and Stephanie’s Astrapia.

Source: Based on Coates 1990. Beehler 1993.

243The administration expressed concern about the size of New Guinean bird hunting parties for a second reason. This was the detrimental impact they could have if they joined with coastal communities and bullied little-contacted inland communities. Apart from control of group size, New Guinean hunters were also restricted to using muzzle-loaders which were suitable for hunting birds of paradise, but less effective for shooting people than bullet-firing guns.73 The main guns used for bird hunting were either 12, 16 or 410 gauge shotguns.74 In order to prevent pay-back killings by hunters in their home areas, they were not permitted to hunt in the vicinity of their own villages.

It became a requirement in 1911 that the employment of more than one assistant was only possible if his employer took up residence in Kaiser Wilhelmsland and became engaged in establishing a plantation or some other business.75

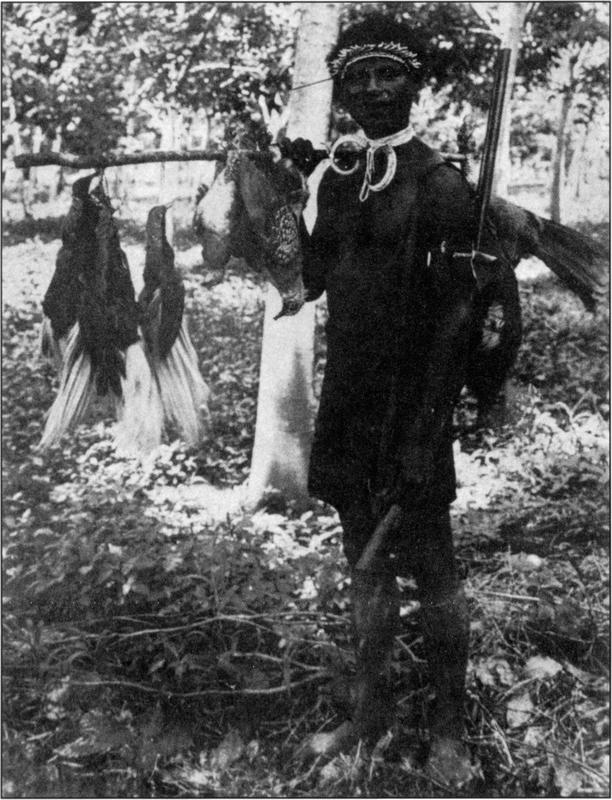

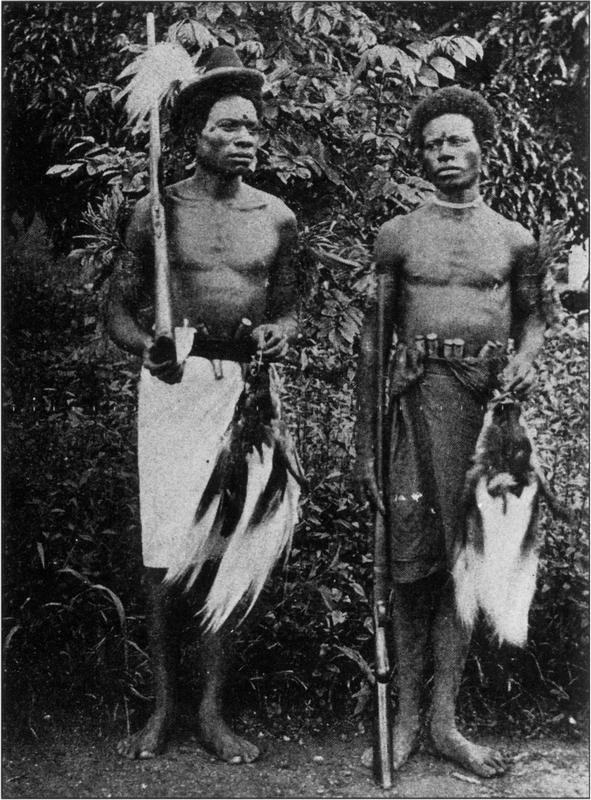

Bird of paradise hunting assistants were New Guineans, Indonesians or Chinese in the employ of Europeans. Each year when the hunting season began, small columns of men could often be seen leaving coastal settlements for inland areas to hunt birds of paradise usually under the leadership of Europeans.76 Plates 38 and 39 show New Guinean hunters after their return from successful hunting trips.

Indonesians and Chinese, initially from Singapore and later from Hong Kong, were recruited by the Germans to work in German New Guinea. The Indonesians willingly came and successfully worked as hunters, traders and plantation labourers, but they returned home after they had saved a few hundred marks. The Germans were unable to persuade them, or others they brought in as plantation labourers, to settle down and cultivate the land.77

In the early 1970s, the old people in the Dreikikir area of the Torricelli Mountains could still remember when the first Indonesian and Chinese hunters and traders came into their area (Figure 48). These hunter/traders worked out of the trading posts established on the coast at Yakamul, Ulau and Suain. They followed the north-flowing rivers inland. Eye-witness accounts suggest that when the Indonesians and Chinese first went inland they were not prepared for long expeditions and did not expect to find large populations lying behind the coastal mountains.78 Most of the Indonesians and Chinese were accompanied by coastal men. Their parties were guided by men from the Torricelli Mountain villages who could speak the Kombio and Wam dialects spoken in the villages they visited. Once contact was made, they usually returned to the same villages and traded goods such as knives, beads, paint, cloth and salt for skins.79 This contact rather than intrusion from the border probably explains how people in the Yellow River area became more proficient in Malay than people further west.80 244

Plate 38: A New Guinean bird of paradise hunter in German New Guinea with his gun and catch, which includes Lesser Birds of Paradise and pigeons. The latter would be for eating.

Source: Gash and Whittaker 1975, from M. von Hein Collection, Sydney.

Some hunters and traders penetrated to villages south of Lumi. When E. W. Oakley, then assistant district officer, was attempting with a surveyor to find a vehicle road route from the Sepik River to Aitape in this area in 1932, their camp was rushed by an armed party of fifty men. Two Vanimo constables recognised a few Malay pidgin words and soon found they had encountered people who had formerly been in touch with Indonesian plume traders. These traders had lived at Yerimi hamlet and Tabatinka village for some months, whilst engaged in bird hunting.81 Alan Marshall82 similarly reports the former presence of 245Indonesian traders in the Lumi area and notes that further west people could still speak a few words of pidgin Malay. At Bogasip village in 1935 people brought bird of paradise plumes to Marshall’s party eager to trade. The plumes were mainly those of the Lesser Bird of Paradise (Paradisaea minor).

Interaction between hunters and local communities

The slaughtering of beautiful birds was only one of the unpleasant aspects of the plume trade. Many people also suffered as a result of this activity and we can assume that new diseases were introduced. Concern about the impact of bird of paradise hunters on inland communities was expressed both by the authors of newspaper articles, for example Schillings 1912,83 and government officials, for example Ebert 1912.84 They were especially concerned about those people uncontacted by the administration who had no means of voicing their complaints. Apart from having their birds and other game shot, their gardens were probably also raided. Commander Ebert of the Cormoran, who in 1912 was making an official political and military report on German New Guinea, stressed the need to recognise local practices. He understood that hill-country people regarded everything that flew and walked around in their forests as their property. To hunt birds of paradise in the forests without the consent of the local land owners had to be seen as a serious breach of their rights. Some bird of paradise hunters took this into account and paid the people who owned the bush where they were hunting. This was evidently the practice of the Chinese and Indonesians visiting the Lumi area. Those who did not pay were frequently attacked as this was the hill-country people’s reaction to unwelcome strangers intruding into their territory.

Unlike most Indonesian and Chinese hunter/traders working in the Sepik area, some European hunters such as Alfred Mikulicz came into conflict with the local people. In August 1912, Mikulicz and two other Europeans were hunting with their assistants down the right bank of the Ramu, eight to ten days’ walk from Alexishafen. Mikulicz had seven men with him and on this expedition they had already been involved in four fights. After setting up camp, he rested there with his cook boy whilst the others went hunting birds of paradise. The camp was attacked by the local people and he was speared to death. The cook boy raised the alarm, but by the time the other hunting groups arrived at the camp, there was no sign of Mikulicz or the local people.85

A number of Europeans, Indonesians and New Guineans hunting birds of paradise in inland regions were attacked in German New Guinea. Those on record are listed below: 246

Table 18: Plume hunters attacked whilst shooting in German New Guinea.

| year | who and where |

|---|---|

| 1907–8 | Indonesian hunter was killed in Hatzfeldthafen area and his firearms seized. Germans made a punitive expedition. |

| 1908–9 |

Umlauft and New Guinean assistant were shot at with arrows while in Rai Coast mountains. Escaped without injury. |

| 1909–10 |

European hunter was killed by Wamba people in hinterland of Herzog Range on the right bank of the Markham River. Punitive expedition killed 40 people and burnt several villages. |

| 1912 June | Peterson had been a medical assistant for the New Guinea Company for about a year, when he decided to go bird of paradise hunting. He was killed inland of Madang. A punitive expedition from 21–26 June arrested the main culprits, killed five men and burnt Bemari village. Police were left to carry out further punitive measures. |

| 1912 July |

Three Chinese and ten New Guinean assistants employed by the Hansa Bay planter Gramms were killed by Kagam tribes inland of Hansa Bay. A punitive expedition was made. |

| 1912 August |

Alfred Miculicz before becoming an independent bird of paradise hunter had been a planter in the employ of the German New Guinea Company. He was killed on the right bank of the upper Ramu eight to ten days’ walk from Alexishafen. Miculicz was one of a group of three European hunters and their assistants who had been involved in four fights with inland communities. |

| mid 1913 | Two Europeans were attacked in the hinterland of Laden. Shot at with arrows whilst bathing in a stream. Rifle fire made the attackers flee. |

| 1913 July | Indonesian and two New Guinean assistants were killed in hinterland of Sarang. Their rifles were voluntarily sent to the coast and given to government officers. |

Sources: Anon 1912d: 139; Ebert 1912; Preuss 1912: 123; Sack and Clark 1979: 277, 292, 322, 354; Sack and Clark 1980: 9–10; Schillings 1912.

247While some hunters were killed, others were lucky enough to escape. The German administration stressed that it was not possible, in terms of the cost and personnel required, to punish all the groups involved in these incidents. Bird hunters and gold prospectors were therefore requested to restrict their activities to areas where there was some guarantee for their personal safety. It was advised that they should not venture beyond those areas where the local people recognised German authority.86

Plate 39: New Guinean bird of paradise hunters in German New Guinea with guns and Lesser Birds of Paradise they have shot.

Source: Lyng 1919.248

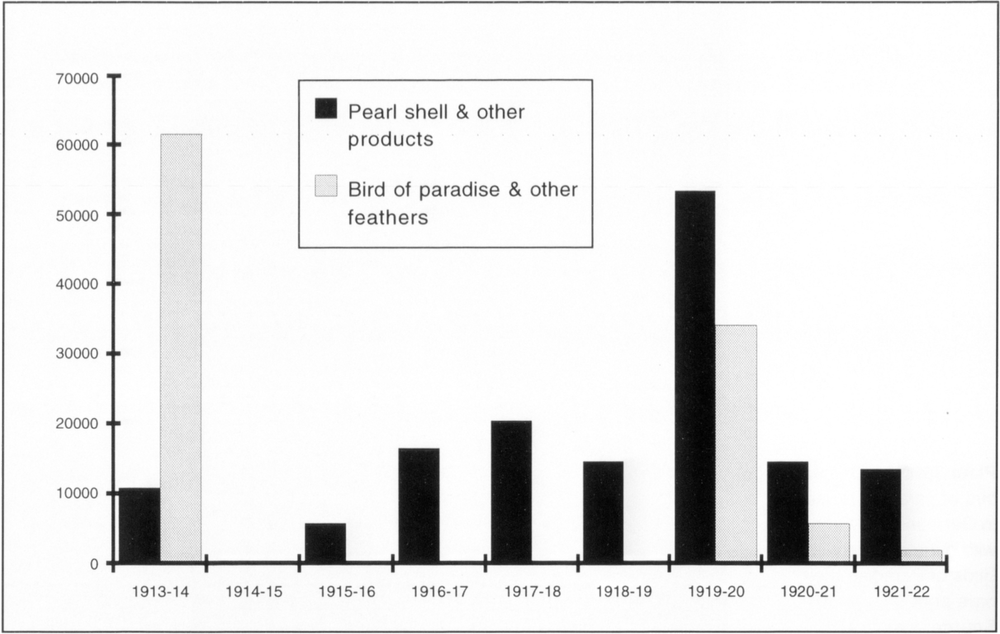

Figure 53: The value of copra and birds of paradise (and other feathers) exported from German New Guinea and the Mandated Territory of New Guinea from 1913–22.

Source: New Guinea Annual Reports 1914–22.

Figure 54: The value of birds of paradise (and other feathers) and pearl shell (and other marine products) exported from German New Guinea and the Mandated Territory of New Guinea from 1913–22.

Source: New Guinea Annual Reports 1914–22.

249Implications of German legislation for Melanesian villagers

When studying a draft of a new ordinance in 1912, Busse, the Privy Counsellor at the Colonial Office in Berlin, raised the issue that the draft did not consider independent hunting by New Guineans. He wanted to know whether they should be required to obtain a licence and pay the required fee in order to hunt cassowaries.87 This was probably recognised as an unenforceable piece of legislation, as the matter was not given any further attention.

Role in development

The two main exports from German New Guinea in 1910 were trade copra and bird of paradise skins. Village production remained dominant as only some 20 per cent of the copra exported was produced on plantations.88 Copra yielded the highest returns. In 1910–11, 9,244 tonnes of copra earned 3,039,000 marks, whereas skins only brought in 171,000 marks.89 This was the case for the colony as a whole (see Figures 53 and 54), but bird of paradise plumes were the main revenue earner for Kaiser Wilhelmsland. This discrepancy between the export earnings of the New Guinea mainland and the New Guinea Islands made Rabaul the financial capital of German New Guinea. By 1909 it had also become the administrative capital as well.

Plume “fever”

Many features of bird of paradise hunting were like prospecting. This similarity was not missed by the administration of German New Guinea who likened bird of paradise hunting to a small-scale gold fever, with all its associated bad aspects and unpleasant incidents, in their 1911–2 report.90

Many prospectors took up bird hunting after unsuccessful prospecting expeditions. This was the case with the three experienced Australian prospectors who were unsuccessful in their search for gold in the upper Markham River area.91 Other men probably combined both activities, and some may have kept their eyes open for stands of wild rubber. In a few cases hunters reported interesting finds. An Indonesian hunter based at a coastal trading station reported oil-bearing deposits near Eitape (Aitape) in 1913.92

The investment by hunters in plantations

According to Paul Preuss,93 a director of the New Guinea Company, the majority of planters in German New Guinea were former company employees. Many took the opportunity provided by the rising plume prices to establish their own plantations. Settlers usually worked in pairs or groups of three when plume revenue was used to fund new 250plantations. One would work their jointly purchased plantation, whereas the other partner(s) hunted birds of paradise. The income derived from the sale of the bird skins paid for its development. This practice was encouraged by the administration, as all licensed hunters were required to clear land and plant about 50 hectares of coconuts each year.

Many planters only survived the seven or more years they had to wait, between the planting and harvesting of their first paying crop of copra, because of the ready cash they got from bird hunting. Their palms did not begin bearing fruit until after 6–7 years of growth and reached full bearing only after 10–12 years.94

One of the pioneer planters who got his start through bird hunting was Adolph Batze of Lae. Accompanied by his father and two brothers, he reached New Guinea from Germany in 1906. Each hunting season the four Batzes went hunting and each man brought in between 200 to 700 birds. On a good day Adolph Batze claims he got 50–60 Augusta Victoria (a subspecies of Raggiana) and several King Birds of Paradise. While in the field, they skinned the birds and treated the skins with arsenical soap.95 The average price paid per bird in 1910–11 was 35–40 marks but in 1911–12 it fell to 30–35 marks.96

In the two years prior to 1 January 1913, thirteen plantations with 20 owners were established in Kaiser Wilhelmsland. These enterprises covered a total of 4,850 hectares and brought under cultivation some 1,138 hectares (Table 19). By the end of 1913, it was envisaged that another 1,000 hectares would be brought under cultivation.97

251Table 19: Planter settlers in 1913 who had established plantations in the last two years and were dependent on income from bird of paradise hunting to finance their plantations. (This list consists of those who signed the petition against the proposed legislation to prohibit bird of paradise hunting.)

| area | owners(s) | plantation size in hectares |

hectares planted | number of coconut palms |

number of employees |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eitape (Aitape) | Bechner | 150 | 30 | 3,000 | 33 |

| Eitape (Aitape) | Piper | 200 | 90 | 12,600 | 50 |

| Boiken | Brinkmann | 150 | 100 | 10,000 | 62 |

| Moem | Peuker | 500 | 100 | 10,000a | 46 |

| Awar | Gramms | 500 | 250 | 30,000b | 80 |

| Hatzfeldthafen | Hahn, W.J. | 500 | 100 | 10,000 | 75 |

| Sarang | Stiller | 150 | 30 | 3,900c | 30 |

| Sarang | Kempt and Sturm | 1,000 | 30 | - | 60 |

| Sangana (Karkar Is.) | Andexer and Merseburger | 200 | 83 | 5,100d | 103 |

| Alexishafen | Penn | 500 | - | -e___ | - |

| not stated | Glasemann and Kempter | 400 | 120 | 10,000 | 93 |

| not stated | Ahr and Gathen | 400 | 20 | 2,000 | 60 |

| not stated | Meiro Company | 200 | 175 | 5,000f | 112 |

Other crops

a. some rice had also been planted

b. 3.5 hectares with 1,400 ficus trees

c. hemp and bananas

d. 12,600 Hevea (rubber) trees

e. some rice was planted in 1913

f. 200 hectares with 45,000 coffee trees

Source: Hahl 1913a: 208.

The plantations ranged in size from small enterprises to large holdings, but their continued existence and development was dependent on bird of paradise skin sales. Without an income from bird of paradise hunting these small independent enterprises did not have sufficient capital to stay afloat, nor were they sufficiently developed to obtain loans or mortgages. The standard of living on these north coast plantations was based on a shoe-string budget, but thanks to bird of paradise hunting they kept going with the expectation that once their coconuts started yielding they would be able to achieve a comfortable standard of living. The option of selling out to big wealthy firms was not attractive, nor in the view of the plantation owners was it in the interests of the colony for a number of reasons. Firstly, unlike the large companies, they were not transitory workers. Owner-planters had a long-term commitment to their plantation and were thus concerned about the well-being of German New Guinea. Secondly, like missionaries, they promoted development as they were dependent on neighbouring villages and for this reason also cultivated friendly relations with them. Thirdly, unlike large companies, they could not afford to recruit staff from distant places, but were dependent on local workers whom they trained. Finally, they obtained food from neighbouring villages in return for trade goods. By supplying villagers 252with iron tools, clothing, and the like, the villagers obtained improved living conditions.

The owner-planters believed that the administration should be able to benefit from the plume boom, but its fees should not be so large as to deprive them of a reasonable return for their efforts. The introduction of the 20 mark export duty was more than they could bear. To obtain profitable returns with such a duty level, a market value of 50 marks per skin was required. This price was rarely obtained at that time. In their view the introduction of a 20 mark export fee as well as an increased licence fee would be ruinous.98

Conservation demands

In Germany there were frequent calls to prohibit the hunting of birds of paradise in German New Guinea. When Governor Hahl was there in 1910, he gained first hand experience of the widespread protests against bird of paradise hunting organised by the Association of Friends concerned with the Protection of Nature, Animals and Birds.99

Those opposing the ban were adamant that not only would it ruin certain planters, but it would also weaken the economy. Their argument was that further taxes would have to be imposed to cover the deficit previously met by hunters’ licence fees and the taxes imposed on exported plumes.

By 1911 the conservation call was gaining momentum in Germany. Many articles appeared in German newspapers dealing with New Guinea in general and birds of paradise in particular.100

For a while it was thought that the birds were free to retreat into the inaccessible mountains of the coastal hinterland,101 as hunters were only operating in the coastal regions of Kaiser Wilhelmsland.102 In a newspaper article dated the 29th of September 1911, Professor Richard Neuhauss,103 an anthropologist, pointed out that this was a totally misguided view which would have tragic consequences. He explained that coastal areas are the natural habitat of many of the species being hunted, consequently they cannot be expected to save themselves by retreating into the mountains. Neuhauss called on the government to prevent the extinction of birds of paradise by prohibiting their commercial hunting.

The German public reacted in different ways. Some were concerned about the birds, whereas others used the issue for political ends. Those interested in the birds fell into three main camps. These consisted of those who proposed a complete ban on hunting, those who would permit some hunting but demanded greater protection, and finally those who wanted to put the birds into reserves where they could be bred in captivity. In contrast members of the Social Democrat party used the issue to criticise Germany’s colonial activities.104 253

There was considerable discussion about breeding birds of paradise in captivity in the same way as pheasants were bred in Europe and ostriches in southwest Africa.105 The administration of German New Guinea declined to be involved in investigating this idea, but agreed to help finance such an enterprise if it was shown to be viable and profitable.106

Several specialists were drawn into this debate. Professor Heck, Director of the Berlin Zoological Gardens, considered that more could be achieved by making rules and laws about bird of paradise hunting than by breeding them in reserves or in captivity. Birds kept in his zoo had not bred. He also mentioned the conservation measure of releasing birds of paradise on Little Tobago in the West Indies;107 see also Chapters 5 and 9.

Further information was also sought. J. Bürgers, the zoologist and medical doctor of the Empress Augusta (Sepik) River Expedition was asked to observe as much as possible about the habits, habitats and numbers of birds of paradise in the Sepik.108 He did not restrict his activities to birds of paradise, but made a general collection which has become a landmark in New Guinea ornithology. He collected some 3,100 specimens of 240 bird species, mainly from the Middle and Upper Sepik.109

By 1912 there was a strong call for a complete ban on the hunting of all species of decorative birds. A large number of articles appeared in newspapers and periodicals protesting against the slaughter of birds of paradise and a resolution was tabled in the German Parliament.110 It was proposed that a ban should be introduced on the 1st of April 1914. If this was enforced, the administration of German New Guinea would have to cease being dependent on the proceeds from hunting and exporting of bird of paradise skins as a reliable source of public revenue. When faced with finding the predicted 40,000 marks shortfall for the 1914 budget, the Colonial Ministry requested that the opinion of the German Financial Minister be sought before going ahead with the proposed ban.111

It was the view of the German New Guinea administration that a total ban on the hunting and shooting of birds of paradise could not be immediately introduced and made to work effectively for two reasons. Firstly, there were no alternative local means within Kaiser Wilhelmsland of raising the shortfall in government revenue as there was insufficient trade copra and little pearl shell, apart from the green snail shell obtained from Tarawai and Walis Islands (Figure 48). Secondly, the plantation enterprises established so far would only be economically viable once their palms started yielding copra, but this was not yet the case and they would be subject to considerable losses if there was a total ban on hunting. The governor was requested to 254determine when a complete ban could be proclaimed without harming established economic interests.112

Berlin was keen to introduce a complete ban as from 1 April 1914 which would expire in May 1915. In preparation for such a ban the administration of German New Guinea was instructed to exclude expected bird of paradise revenues from the 1914 budget. They were also instructed to inform intending settlers and plantation owners of Kaiser Wilhelmsland that they could no longer expect to finance their enterprises from bird of paradise hunting.113

Over the years the administration of German New Guinea had taken considerable measures to protect the birds and at the same time avert a hunting prohibition. They had licensed hunting, declared three special reserves, prohibited hunting for six and a half months each year and levied high taxes on rare species. When the Secretary of the Colonial Office instructed Hahl to raise fourfold the export duty on plumes, he responded by saying that this rise was less acceptable than a complete ban on hunting.114 In 1913–14 Hahl planned to restrict hunting to those involved in the economic development of Kaiser Wilhelmsland, namely the planters and those engaged in activities such as prospecting which opened up hitherto uncontacted areas. He intended to issue only 20–30 licences and had declared three closed conservation areas. These measures in his view would adequately protect the birds of paradise from extinction.115

Most staff of the German Colonial Office in Berlin saw the hunting and exporting of bird of paradise skins from German New Guinea as a short-term source of private and public revenue that could now be discontinued.116 The Secretary, Dr. Solf, personally supported the banning of bird of paradise hunting. His views and particularly his address to the German Agricultural Society resulted in congratulory letters from a number of conservation organisations.117

By 1913 the conservationists were adamant that the measures proposed by the administration of German New Guinea were inadequate to ensure the survival of birds of paradise. Nature lovers in Germany wanted nothing less than a total ban on bird of paradise hunting. The Association for the Protection of Birds petitioned the Kaiser of Germany and the King of Prussia on the 21st of February 1913 to press for a ban on the shooting of birds of paradise so that the decimated birds would have a chance to recover.118 The German Colonial Office in Berlin was keen to enforce a complete ban, comparable to that in force in British New Guinea, but was hesitant to do so as they envisaged more hunters would infiltrate from Dutch New Guinea.119 The Kaiser believed that the rise in export dues did not improve the situation and that the only solution was a complete ban 255on the shooting of birds of paradise. He requested that such a ban be enforced immediately without waiting for the Dutch to introduce comparable legislation for Dutch New Guinea.120 The Secretary for the Colonial Office carried out these instructions and advised the Governor of German New Guinea to impose a complete ban for one year. During this period district officers were to review the situation by surveying what was known about the habits and breeding seasons of the birds so that this information could be used to ensure that the birds were saved from extinction.121

Australian administration

Australian occupying forces took over German New Guinea in September 1914. Until a peace treaty was signed and the future sovereignty of German New Guinea determined, international law did not allow the Australians to change existing legislation except in cases of military necessity.122 The German law in force permitted licensed hunters to shoot birds of paradise in the Mandated Territory of New Guinea from May 1915.

In German times there had been some smuggling of bird of paradise skins across the border into Dutch New Guinea during the hunting ban and this continued after the Australians took over in 1914. The Australians found it difficult to control the coastal movement of Germans into Dutch New Guinea. This led to a standing patrol being established at Vanimo to prevent German citizens from making contact with enemy agents in Dutch New Guinea.123 The Australians suspected that uncensored letters were being smuggled to Hollandia by coastal schooners involved in the illegal trafficking of bird of paradise skins.124

Apart from possible espionage during smuggling activities, the Australians monitored bird of paradise hunting because it meant that certain civilians possessed firearms. The military administration took steps to control the possession of these weapons. Each owner was required to obtain a licence from the senior military officer in his district.125

The military administration did not interfere with the hunting licences in force nor did they take steps to seize the large quantity of plumes stored for export. Although it had been illegal from 1913 to import bird of paradise skins into Australia,126 the Australian military administration imposed no restrictions on their export to other countries. However, since bird of paradise hunting was prohibited in neighbouring Papua, it was widely recognised that the Commonwealth government would eventually take steps to discourage and prohibit the export of plumes from former German New Guinea.127

256These steps began in 1915. In August of that year, any persons possessing more than 3 bird of paradise skins, 12 goura pigeon crests or 6 heron (egret) sprays were required to register their collections.128 Customs duty was imposed on bird plumes in 1916; see Table 20.

Table 20: Customs duty imposed on bird plumes in New Guinea in 1916.

| species | rate |

|---|---|

| birds of paradise (portions and feathers of one bird) | £1 each |

| goura pigeon (portions and feathers of one bird) | 5 shillings each |

| cassowary feathers | 12 shillings 6 pence per lb |

| heron (egret) feathers | £25 per lb |

Source: Customs Duties Ordinance of New Guinea (Rabaul) Gazette, 15 May 1916: 47.

After the end of the First World War in November 1918 the plume trade resumed. During this period the export value of bird of paradise skins fell behind not only copra but also pearl shell and other marine products; see Figures 53 and 54.

The question which is not easily answered is how many of the bird of paradise skins and other feathers exported from the Mandated Territory of New Guinea were skins brought out of storage after the war (as happened in Merauke) or were from birds hunted at the time. Many were probably recently acquired as the months with the highest exports (May-June in 1919–20 and August in 1921–22) fall in the hunting period for birds of paradise.

The plantations which had been established during the German colonial period were expropriated by the Australian Expropriation Board as part of the international policy adopted by the victors of World War I of making Germany pay reparations. It also reflected the antagonism felt by Australians towards Germans. This had begun when the Germans annexed northeast New Guinea and had increased during the war.129

The president of the Australian Expropriation Board who made decisions about expropriations in New Guinea was Walter Lucas, a representative of Burns Philp Company, one of the largest Australian trading companies operating in the Pacific. In retrospect the plantation settlers in Kaiser Wilhelmsland were poorly treated. During the war the 257settlers had continued to develop and expand their plantations, never envisaging, even with Germany’s defeat, that they would be dispossessed. By the end of the war these plantations were viable commercial enterprises, but their developers were never compensated for their efforts.130

In 1920 an export ordinance was passed. Any individual, firm or company who possessed plumes they wished to export had to register them with the Department of Trade and Customs in Rabaul. These plumes had to have been acquired before the end of February 1920 and exported before early March 1921.131 The closing date was later extended to the end of December.132 On the 1st of January 1922 bird of paradise skins were a prohibited export from the Mandated Territory of New Guinea as former German New Guinea had now become.133 In order to prevent bird of paradise skins from being smuggled into Dutch New Guinea, the administration reestablished an office at Vanimo. It had been withdrawn during the war. A district officer was based there until after 1931, when plume hunting became illegal throughout Dutch New Guinea. It was not until 1936 that Wewak was made the main government station on the Sepik coast.134

Special licences were only granted in the Mandated Territory of New Guinea, as in Papua, to the duly accredited agents of a government, a museum, zoological or acclimatization society, or other scientific institution. Legislation passed in 1922 allowed such agents to either shoot or capture and subsequently export birds of paradise, goura pigeons and white herons under permits restricting the numbers collected.135

Notes

1. This was how the first Chinese came to Papua New Guinea. Other Chinese were brought by the German administration to work as labourers, initially from Singapore, but later from Hong Kong (Wu: 1977: 1047; Hahl 1980: 145).

2. Parkinson 1979: 40.

3. A variant spelling of kelapa, the Malay word for coconut.

4. Kachau, Saulep and Pinjong 1980: 18.

5. Hahl 1980: 109–10; 120. This means that itinerant traders and hunters from Dutch New Guinea were not welcome in German New Guinea, whereas Indonesians who came either to work as hunters or traders, or to settle, were encouraged. They willingly came to work for German employers as hunters and traders, but returned to Dutch New Guinea after they had saved a few hundred marks. None wished to settle and cultivate the land (Hahl 1980: 144).

6. A similar restriction led to the end of the Makassarese trepang industry 258on the north coast of Australia in 1906. From that date trepang collecting licences were only issued to locally owned boats (Macknight 1971–2: 284).

7. Hahl 1980: 110.

8. Seiler 1985: 147.

9. Molnar-Bagley 1982: 25.

10. Gell 1975: 2.

11. Cheesman 1960: 27–8.

12. This remarkable woman made many expeditions to the Pacific collecting insects for the British Museum and other museums from 1923–54. Overall she spent some six years in New Guinea (Huie 1990).

13. Cheesman 1941: 184–5; also in 1949: 270–1.

14. Mackenzie 1934: 313.

15. Hahl 1980: 109, 120.

16. Deklin 1979: 33.

17. Robinson 1934–5.

18. Gilliard 1969: 26–7; Townsend 1968: 63–6.

19. Bryant Allen personal communication 1991.

20. Robinson 1934–5.

21. Schultze-Westrum 1969: 300.

22. Cheesman 1938a: 42.

23. Although slow to be colonised, New Guinea has not lacked in flag raising. The first instance was as early as 1545 when New Guinea was claimed for Spain when de Retes landed just east of the Mamberamo River mouth in what is now West Papua (Figure 42).

24. see Whittaker et al 1975: 459.

25. van der Veur 1972: 277.

26. In 1884–6 Germany took possession of Kaiser Wilhelmsland (northeast mainland New Guinea), the Bismarck Archipelago, the Solomon Islands and islands in Micronesia (Hahl 1980: 6). The Bismarck Archipelago was included as German traders and labour recruiters had been active, with other nationalities, in the Duke of York Islands and the Gazelle Peninsula of New Britain for almost a decade.

27. Jacobs 1972: 486.

28. Jacobs 1972: 486–7; Sack and Clark 1979: 133–4: May 1989: 114.

29. Sack and Clark 1979: 143.

30. Jacobs 1972: 487.

31. Jacobs 1972: 486–90: 496–7.

32. Budup is on the northern shore of Sek Harbour some 15 kilometres north along the coast from Madang. Local traditions and recovered artifacts indicate that European sailors probably repaired a beached vessel there. In the 1920s one old man recounted that when his father was a boy, he had seen a sailing ship at Budup. This would have been in about the 1830s. It had been damaged and was dragged ashore and repaired in the very same hole as Kilibob, a major mythological hero, is said to have built his ship. Local residents report that planks, hammers and a chain were once present at this site. Father Kirsch, the missionary at Sek, and Franz Moeder obtained some ship’s fittings, four steel daggers and two bronze statues at this location and from surrounding villages. The daggers had 259carved horn handles and rusty blades. The two bronze statues were carved in considerable detail with breast and leg plates, a helmet with horns and each figure held a sword. Each statue was mounted on a decorated black ivory base. They were considered to be Portuguese artifacts. The artifacts were kept in the Sek school for many years before Father Hirsch packed them up and sent them to a museum in Europe (Mennis 1979: 92–5). Their current whereabouts are unknown to PNG National Museum staff.

A bronze cannon was thrown overboard from a Dutch sailing boat in the vicinity of Arop village west of Aitape to enable it to float free of a sandbar. The Catholic mission acquired the cannon and sent it to Marienberg, a large mission station on the lower Sepik. The initials VOC are marked on the cannon, signifying the Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie/Dutch East India Company. The canon is listed as File No. 272 in the National Cultural Property File at the PNG National Museum.

The Russian scientist Miklouho-Maclay (Maklai) lived on the Rai Coast of what is now the Madang province in September 1871 to December 1872, June 1876 to November 1877 and March 1883 (Miklouho-Maclay 1982).

A silver bracelet of recent Indian origin, with an attachment holding a Greek coin made between 344 and 334 B.C., has been found just inland of Wewak beach (Borrell 1990). I suspect this bracelet was probably lost by one of the Indian soldiers captured by the Japanese in Malaysia or Hong Kong and brought to work for them in the East Sepik, especially from But to Wewak (see Melnnes 1992: 227).

33. Bodrogi 1953: 91–2; Molnar-Bagley 1993: 17–18, 53.

34. Parkinson 1979: 35–6.

35. Brookfield with Hart 1971: 136.

36. The coconut fragments recovered from the Aitape skull site (Hossfeld 1965) and from the Dongan site (Swadling et al. 1991) indicate that coconuts have been present on this coast for at least 5,800 years, but the historical evidence suggests that the people resident on the north coast have restricted its availability.

The relative scarcity of coconuts may explain why coconut cream and taro pudding was a traditionally important food on the north coast. See Swadling (1981: 52) for a photo of this pudding being prepared in the Madang area.

Wallace (1986: 462) reports that coconuts were also a luxury in the Aru Islands in the 1850s. There people were reluctant to plant a nut which would take 12 years to bear. Any planted nut had to be watched night and day to prevent it from being dug up and eaten.

Ishige (1980: 340) also reports that coconut oil and cream have only recently become common in daily meals amongst the Galela of northern Halmahera. Traditionally coconuts were not planted as a cash crop and some families lacked even a single palm for household use.

The lack of coconuts on the north coast of Dutch New Guinea, also meant that like Kaiser Wilhelmsland, its economy was initially dependent on plume hunting (Wichmann 1917: 389).

However, this pattern of culturally induced scarcity was not the case along the entire north coast of New Guinea and nearby regions. As already mentioned in Chapter 11, at Jama (Jamna) Island off Takar village on the north coast of West Papua (Figure 42), Abel Tasman reports obtaining 6,000 coconuts and 100 bags of bananas by barter in 1642 for knives made by his sailors from metal hoops (Forrest 1969: ix).

26037. Otto Finsch observed this in 1885, see Wiltgen 1971: 331; Reina 1858 cited by Lilley 1986: 63.

38. Mennis 1981: 14; Mary Mennis personal communication 1993.

39. Oliver 1961: 237.

40. Peter Sack personal communication 1991.

41. Ordinance 1891; Rose 1891.

42. Rose 1892.

43. Hahl 1910a; Rose 1892; Sack and Clark 1979; 330.

44. Sack and Clark 1979: 315.

45. Hahl 1980: 114.