13

Conservationists protect Papua’s birds

Natural history collectors

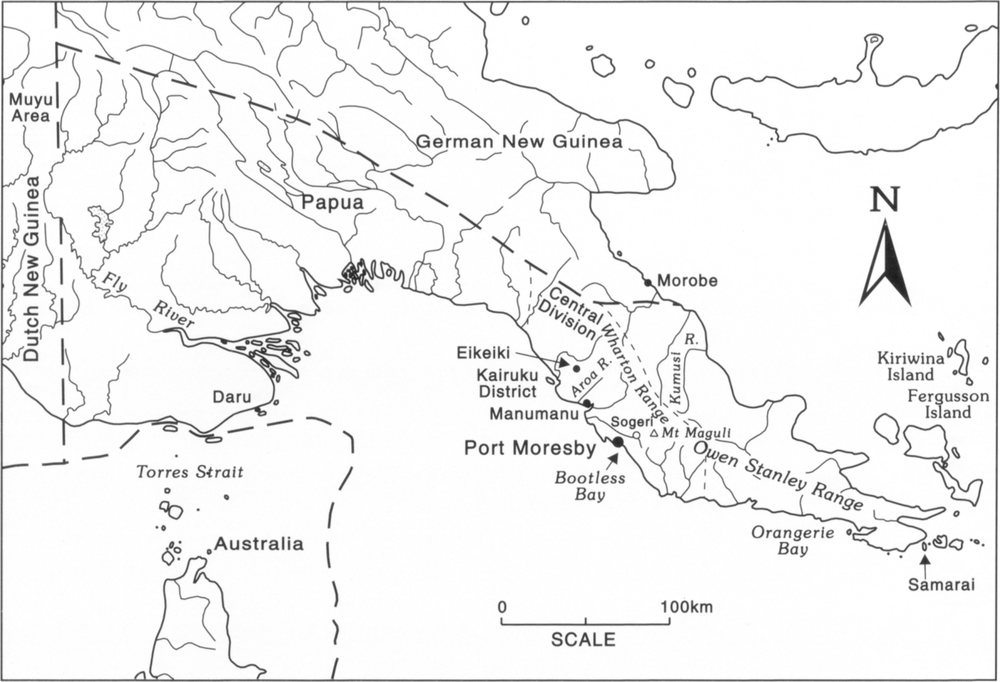

Natural history collectors became interested in British New Guinea1 after the Raggiana Bird of Paradise was first reported at Orangerie Bay (Figure 55) in 1873 (see Chapter 4). Collecting natural history specimens was a profitable activity as museums and collectors paid high prices for new and rare species. Some collectors, such as Carl Hunstein, combined gold prospecting and natural history collecting. During one of his expeditions in 1884, in the mountains some 90–105 kilometres from Port Moresby at Mount Maguli in the Owen Stanley Range, Hunstein was the first European to see the Blue Bird of Paradise.2 There was renewed interest in British New Guinea after this discovery.

Although profitable, natural history specimen collecting and exploration were risky undertakings. In 1884 there were two expeditions to Papua supported by competing Melbourne newspapers. Bird collecting was part of their activities. One of the members of the Argus expedition, William Denton, died of fever on the southern watershed of the Owen Stanley Ranges. Koiari villagers carried him to Berigabadi village some 24 kilometres from Sogeri (Figure 55), where he was buried.3

Other expeditions, especially those in high altitude areas, had tragic consequences for local assistants. In 1905 A.S. Meek went into the upper Aroa area on the southern watershed of the Wharton Range. Some of his hunters became ill with the cold and one man died. This suggests that Meek did not ensure that his hunters had clothes to cope with the cold in high altitude areas. It is therefore not surprising that his carriers deserted him on a subsequent expedition on the upper Kumusi River in 1907.4

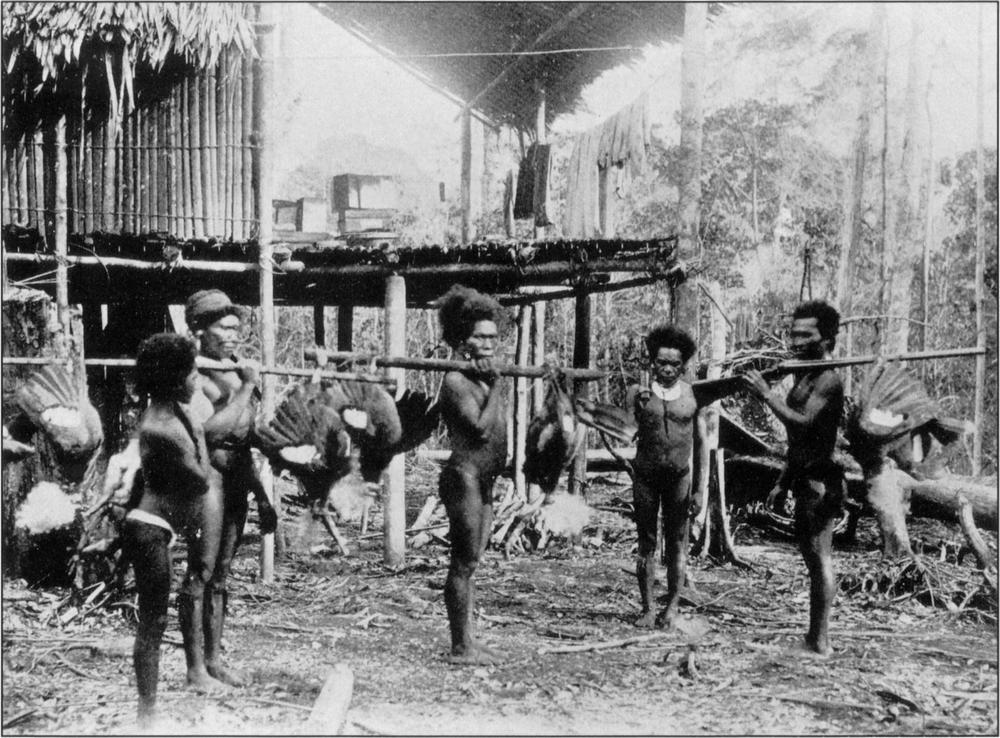

Natural history collectors report that they paid villagers for permission to hunt birds on their land, or paid the villagers for the birds they brought to their camps (Plate 40). The chiefs in the Kairuku 264District required a fee before any birds could be shot in display trees on their land. They considered the birds to be their property. As Pratt commented, this practice amounted to a local game law.5

Figure 55: British New Guinea (became Papua in 1906).

In 1903, in the upper Aroa River area, A.S. Meek describes how he had as many as 150 to 200 snared birds of paradise in his camp. These birds had been captured by local villagers and brought in bound with nooses to long sticks. Meek purchased most of the birds offered to him, released the females and kept only the males for his collections. The birds had been caught by placing a loop on the bough of a tree. This loop was connected by a long twine to the hunter who concealed himself nearby. He pulled the snare as soon as a bird stepped inside the loop and in this way captured the bird.6

Protective legislation

In line with international trends and British colonial legislation, the British and Australian administrations introduced a number of ordinances which initially controlled natural history specimen collecting and later prohibited hunting for natural history specimens and the millinery trade in Papua.

By 1894 there was sufficient concern about the number of birds being hunted in British New Guinea that legislation was introduced to protect them from extinction. The Wild Birds Protection Ordinance of 1894 was passed to protect the colony’s wild birds; this legislation states:

265Our knowledge of the birds of the Possession is as yet very far from being complete, but it is sufficiently great to make it manifest that restrictive measures are necessary in order to preserve certain kinds from speedy extinction.

It would not be possible to prepare an inclusive law that could at once embrace all the different species that may require now or hereafter to be put under protection. The Ordinance therefore provides that protection may be extended from time to time, as may be found necessary, to any species that extended knowledge and greater experience show to be in need of it.

By a Proclamation issued under this Ordinance the destruction or capture of all wild birds, except birds of prey, is prohibited on the watershed of the harbour of Port Moresby, and on the islands of Samarai and Daru. This was shown to be very necessary by the fact that the feathered fauna in the neighbourhood of Port Moresby has twice within the last six years been ruthlessly and inconsiderately slaughtered, so that for months hardly a singing bird was heard in the neighbourhood.

Plate 40: Hunters with birds acquired after a few hours hunting at Eikeiki, (Keke) near Bakoiudu in Kairuku District. These birds were obtained for a natural history collector.

Source: Pratt 1906.

266The 1894 Ordinance also prohibited the collecting of two rare birds of paradise found on Fergusson and other islands in the D’Entrecasteaux group.7 Large numbers of birds continued to be killed by collectors. Further restrictions were imposed on their activities in 1897. The British administration did not consider their occupation as an industry worthy of encouragement.

Formerly the collector had to incur danger where now he is perfectly safe. He had, some years ago, to cut his own track, to find his own way, and it was difficult to obtain native assistants. Now he generally follows up tracks cut by Government; he can employ native assistants almost anywhere; and can thus shoot down the birds of a district in a short time. Ordinance No. VI of 1897 imposes on the collector a licence of £5, and a licence of £1 for each shooting assistant. It does not appear that this licence has any effect in diminishing the number of collectors. It will soon be necessary to proceed a step further and to limit the number of birds of certain species that any collector may kill under his licence, for it would be a great mistake to suppose that birds of paradise are plentiful in the Possession. Only two species are common; some are confined to certain altitudes; others to a few small isolated spots that lie far apart. It would be easy to reduce some kinds to practical extermination, a matter that should not be left till it is too late. It may be, however, that when other forms of employment are provided the number of collectors may be less.8

In 1907–8 the sum of £103 was raised in revenue by issuing bird collectors’ licences. Most of the licences were issued for the Central Division of Papua, raising the sum of £92, with £6 for Eastern Division and £5 for Western Division.9

In early 1908 Sir William Ingram sponsored Charles Horsbrugh to collect birds of paradise in Papua for the British Zoological Society. Horsbrugh based his expedition at Madiu inland of Eikeiki in the Owen Stanley Range and obtained skins and live specimens of birds of paradise and other species.10

According to Archibald Whitbourne, a plume hunter working from Bootless Bay near Port Moresby, the valuable Blue Bird of Paradise was difficult to obtain. It could only be found in the interior mountains and a hunter once there only rarely sighted a plumed male. This was not the case with the Raggiana Bird of Paradise. In good years a European hunter and a team of Papuans might bag 600–700 male Raggianas with their shotguns. The average market value of a Raggiana plume was one pound sterling, whereas the King Bird of Paradise obtained £20–30.11,12

The progressive legislation adopted in British New Guinea was not locally inspired, but a feature of British colonial legislation initiated in India. The shipment of wild bird plumes for the millinery trade from 267India was prohibited in 1902. After the founding of the Society for the Preservation of the Wild Fauna of the Empire in 1903, similar laws were implemented in other British colonies (see Chapter 5).

The newly established Australian administration managed to prohibit plume hunting in Papua, despite considerable local protest, just as the demands of the European plume boom caused market values to rise higher than ever before in 1908. The Wild Birds Ordinance of the 9th of December 1908 made it illegal to capture, willfully destroy, buy, sell, or deal in the skin, feathers or plumage of birds of paradise, goura pigeons and ospreys. Only the duly accredited agent of a museum, zoological society or some other scientific institution could now obtain a permit to shoot these birds. An amendment made in 1909 also allowed the capture of these prohibited birds for purposes of acclimatisation in some other country. The 1908 Ordinance was further amended and consolidated by the Birds Protection Ordinance of 1911.13

Despite such legislation, plume hunting continued in western Papua. Many hunters illegally crossed the border into Papua from Dutch New Guinea and sought plumes in Papua. Their story is told in Chapter 10. It was not until 1926 that this was stopped. That year the Dutch authorities made it illegal to hunt in the Muyu area (Figures 38 and 41) and thus effectively closed the border area with Papua to plume hunters.

An assessment of current and potential exports from British New Guinea published in 1906 by the naturalist, A.E. Pratt, did not even consider bird of paradise skins worthy of mention. He considered cattle, chillies, cocoa, coffee, copra, gold, rubber, sandalwood, trepang and tobacco to be British New Guinea’s potential income earners.14 By that date a large number of gold-mining ventures had been established in Papua. Today one can only speculate as to whether the administration of Papua would have so promptly prohibited plume hunting in 1908 if at the time promising mineral prospects had not been found.268

Notes

1. British New Guinea was first a Protectorate from 1884 until 1888 and then a Colony. In 1906 the Commonwealth of Australia was given full responsibility for the Territory of Papua.

2. Gilliard 1969: 250.

3. Armit 1884 cited by Whittaker et al 1975: 274; Gilliard 1969: 445.

4. Gilliard 1969: 448–9.

5. Pratt 1906: 135.

6. Meek 1913: 132, 150.

7. The Wild Birds Protection Ordinance of 1894.

8. The Bird Collectors Ordinance of 1897.

9. Papua Annual Report 1907–8: 125–7.

10. Horsbrugh 1909.

11. Gilliard 1969: 24–5.

12. By 1910 plume hunters had penetrated into the mountains behind Morobe Station in German New Guinea (Figure 48) and had found the Blue Bird of Paradise to be common there. In that year the price for the Blue Bird of Paradise fell to 30 shillings (one and a half pounds). Some specimens were even taken back alive to Europe (Gilliard 1969: 24–5; Downham 1911: 43–44).

13. The Wild Birds Ordinance of 1908, The Wild Birds Amendment Ordinance of 1909 and The Birds Protection Ordinance of 1911.

14. Pratt 1906: 335–43.