10

Copra, birds and profits

in the Merauke region

The establishment of Merauke

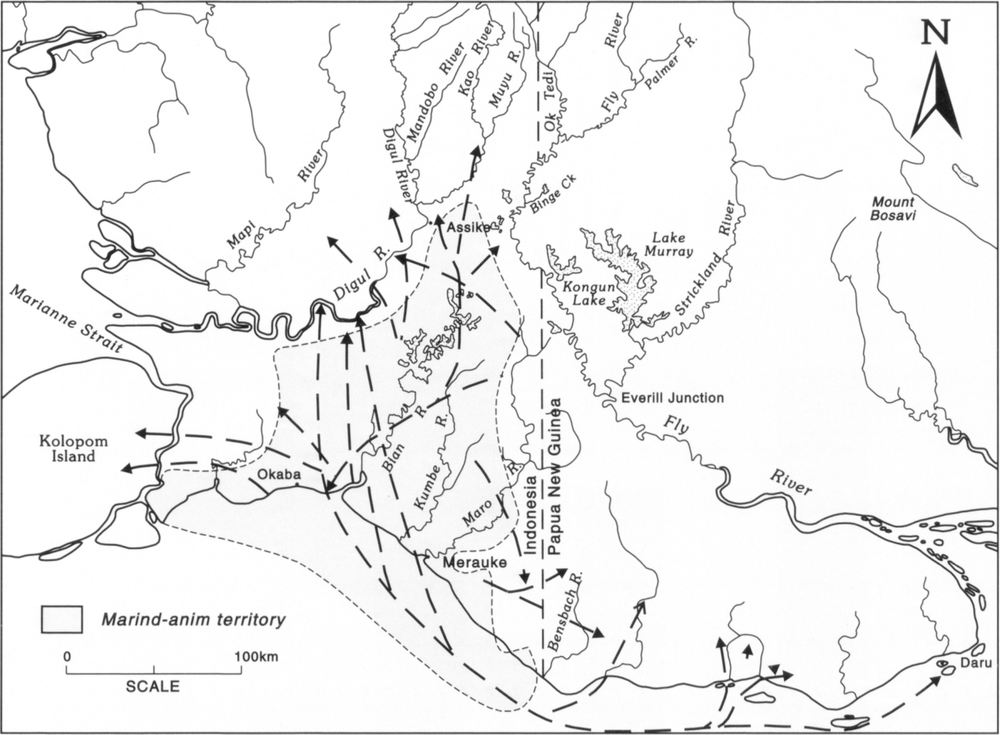

The Merauke coast of New Guinea (Figure 38) was not brought under effective government control until early last century. The Dutch were prompted to take action after the administration of British New Guinea1 made an official complaint in 1891 about the frequent raids being made across the border by the Marind-anim (Tugeri).2 To show their good intentions the Dutch established a station at Selerika (Sarire) on 7 December 1892. This was the second Dutch Station to be established in New Guinea; the first was, as mentioned above, Fort Du Bus at Lobo in Triton Bay in 1828. The Selerika Fort was located close to the border and was manned by 2 Europeans, 10 Indonesian soldiers and 10 convicts. A few days after its establishment one soldier was already dead and 10 wounded; the station was then quickly withdrawn.3

During the 1890s the Dutch were unable to halt the Marind-anim raids across the border. The Administrator of British New Guinea, Sir William MacGregor, actually led an attack which routed a Marind-anim raiding party on ‘Papuan’ soil in June 1896. Despite this confrontation further Marind-anim raids were made in 1900 and 1902.

It was not until the Dutch established a garrison with 100 troops at Merauke in mid February 1902 that the Marind-anim began to be effectively discouraged from raiding.4 Relations then began to be established between the Marind-anim and the Dutch (Plate 25). The superiority of Dutch weapons would have been clearly demonstrated when 2,000 Marind-anim failed in an attempt to take Merauke in 1902.5

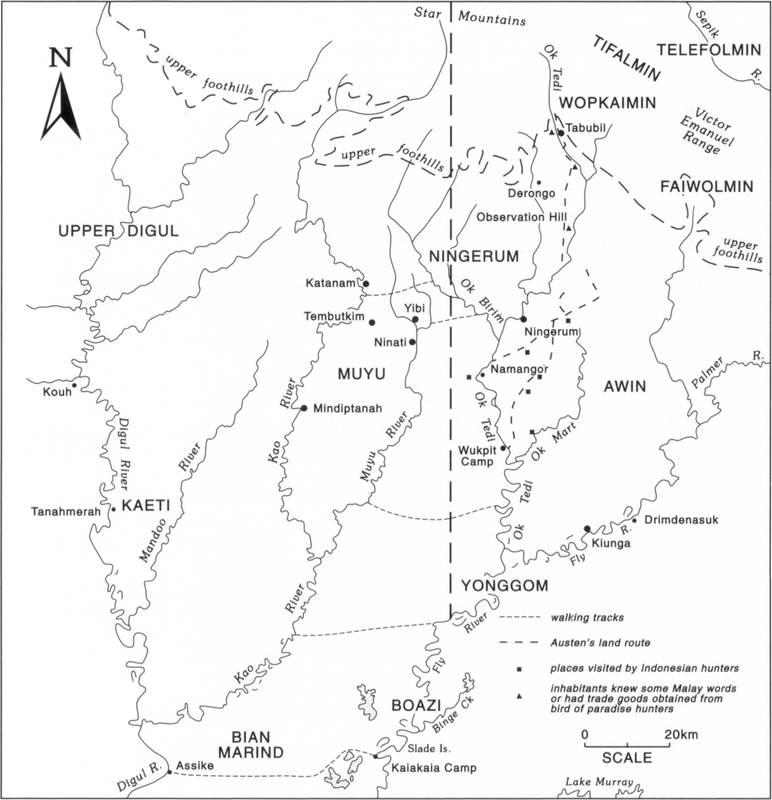

Marind-anim raiders travelled remarkable distances by canoe and on foot. Figure 39 gives some idea of the extent of their journeys. Although coastal raids into British New Guinea ceased soon after the establishment of Merauke in 1902, inland raids were still being made to the Digul as late as 1912.6

176During the early years of contact, strangers who ventured too far from Merauke risked their lives. A.E. Pratt, an English naturalist interested in collecting birds near Merauke, visited the station two months after it had opened. After assessing the local situation he departed at the first opportunity ten days later. The evident hostility of the Marindanim was enough to discourage any thoughts he had of bird collecting.7

Other individuals decided to stay. An Englishman named Montague was the first missionary to live among the Marind-anim in 1896, but the first mission station was not established until 1905. A number of Chinese and Indonesian traders as well as run-away convict labourers also ventured out from Merauke. Many were killed by the Marind-anim.8

By 1905 the situation had improved sufficiently for the Dutch to withdraw their garrison. In 1907 a police post, later an administrative post, was established at Okaba, some 90 kilometres west of Merauke. This post may have been established after a Chinese trader based at Kaiburse had been killed by Sangase villagers from further west. They took the trader’s four Marind-anim assistants to their village. To avoid being beheaded like their employer these four assistants decided to discard their clothes and abandon their foreign habits.9

Plate 25: Establishing relations between the Marind-anim and the Dutch in Merauke in 1902.

Source: Courtesy of Fotobureau, Koninklijk Instituut voor de Tropen, Amsterdam.177

Figure 39: The raiding routes of the Marind-anim.

Despite such incidents, Chinese and Indonesian traders continued to live among the Marind-anim. One of these was Kure Kiong Sioe, a man with Chinese and Indonesian parents. He married a Marind-anim woman, learnt her language and was initiated. His knowledge of the mayo initiation ceremonies was subsequently recorded and in later years he worked as a government interpreter.10 This interaction and contact with plume traders and hunters probably explains how sambi and variants of this word (all being variants of sambut, a Malay greeting) became common in the Middle Fly region.11

After 1907 Dutch military patrols expanded the area under Dutch influence and considerable efforts were made to explore the hinterland accessible by the Digul, as well as the shorter rivers east and west of Merauke.12 This exploration was undertaken in the belief that by opening up the territory economic development would be promoted. Anyone able to establish a business was encouraged by the government, as the maintenance of Merauke and, to a lesser extent Fakfak and Manokwari, was a considerable burden on the financial resources of the Dutch East Indies.13

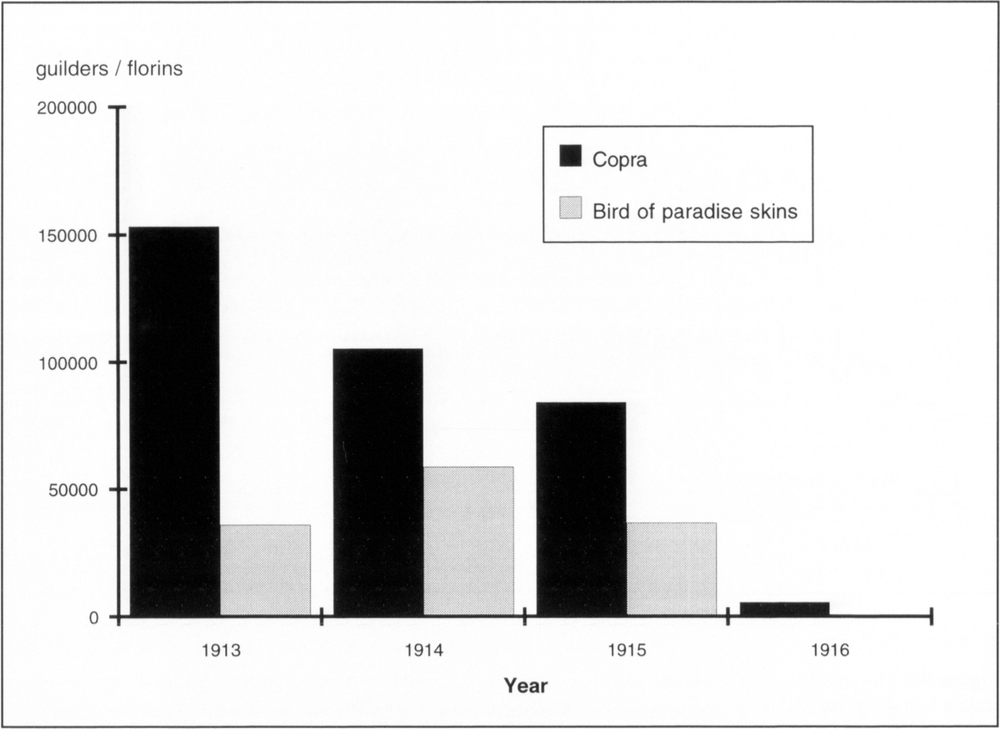

The Merauke Trading Company was established in 1903.14 By 1910 there were fourteen Europeans or part-Europeans employed by the government, two European traders and about twelve Chinese traders at 178Merauke. The Marind-anim had traditionally kept large stands of coconuts for symbolic and religious reasons.15 In 1902 they had hundreds of thousands of coconuts. This made copra trading a profitable venture, a development not possible on the north coasts of Dutch New Guinea and mainland German New Guinea (see Chapter 12). Trade copra quickly became the principal export from Merauke; see Figure 40. Lacking coconuts to trade, the people inland of the Marind-anim were given their first tenuous experience of the vagaries of world trade systems through their contact with bird hunters.

Figure 40: The value of copra and bird of paradise exports out of Merauke from 1913–16. (In 1918, 30–35 guilders or florins was equivalent to 3 pounds sterling).

Source: Based on Historical Section of the Foreign Office, London 1920: 27.

The plume hunters and traders

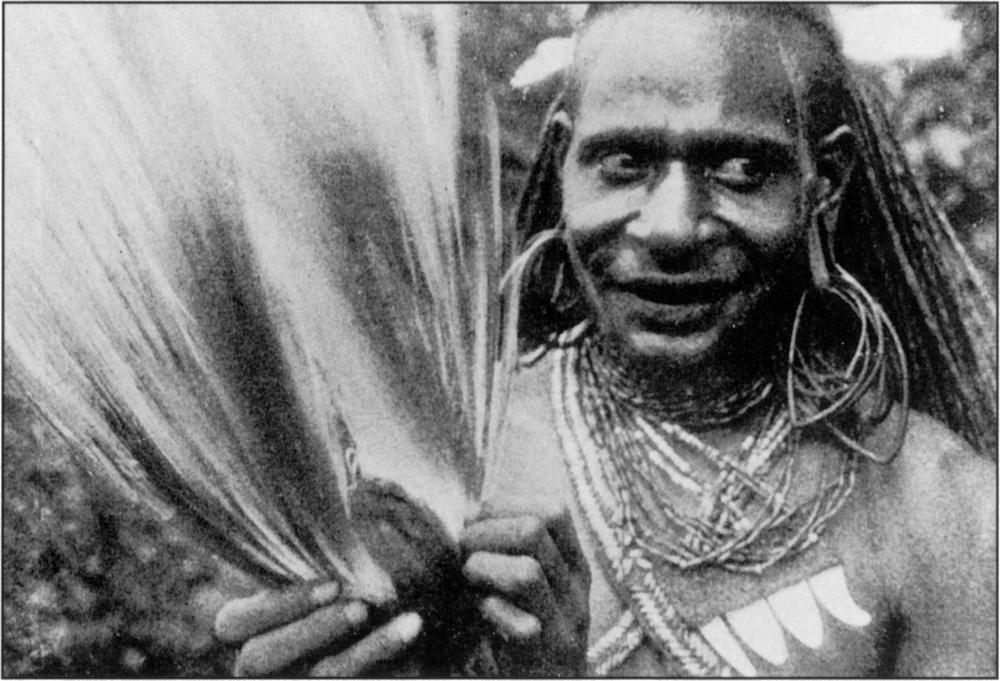

Most of the bird of paradise skins exported by traders from Merauke prior to the 1908 plume boom were obtained from local (Kaiakaia)16 hunters who brought them to the coast (Plate 26).17 This changed when the European and American markets began paying higher prices for plumes during the European plume boom. It soon became apparent 179that local hunters could only shoot a small number of the potential stock of birds with their bows and arrows. A hunter with a gun could make large profits. One visitor to the area commented:

Plate 26: Marind-anim man with Greater Bird of Paradise skins.

Source: Nielsen 1930.

Everyone who could obtain a rifle and supplies, moved as quickly as possible into the interior, before the rumour of the price rise could penetrate that far. [During the early years of the boom it was possible] … to purchase a bird of paradise or the right to shoot one from the local inhabitants for a box of matches or a few large nails.18

In exchange for items worth a few shillings at the most, hunters obtained bird of paradise skins worth more than two pounds each. Large profits were made as prices continued to rise.19

More and more people were drawn to Merauke by the prospects of making their fortune from birds of paradise. They were attracted by the prospect of obtaining substantial profits with relatively little outlay in a short period of time. Europeans, especially Australians, Indonesians from Ambon, Kei and Timor and Japanese and Chinese came to take part in the hunt.20 The Chinese specialised in providing the hunters who lacked business capital with rifles and provisions.

Motor boats were obtained from as far afield as Singapore and Brisbane. All types and brands appeared. As long as they could float and travel some distance they were put into use. One hunter made himself a cheap and easily managed craft by fitting an old Ford 180motor in a large dinghy. This motley collection of motor boats allowed an ever increasing number of hunters to penetrate deep into the interior.

Each boat contained at least five men. They carried enough supplies for approximately four months. These included provisions, weapons, ammunition and a good supply of large and small knives, axes, pickaxes and other iron implements, tobacco and strings of beads to exchange with the Kaja-Kaja’s for birds of paradise. The boats, in spite of their limited space, had to serve as a base for the hunters throughout the trip.21

Plume hunters were usually accompanied by locals who acted as guides and interpreters. For example, the Bian River people took hunters to the Fly River, whereas the Muyu acted as guides eastwards to the Ok Tedi and beyond (Figure 38). In both cases the guides were going into areas where related languages were spoken and where they had either recently established friendly contacts or had traditional trade ties. However, some hunters seem to have taken New Guineans from other areas along as marksmen. Both the Chinese and European hunting parties observed by W.F. Alder, an American adventurer, had marksmen from the Port Moresby area.

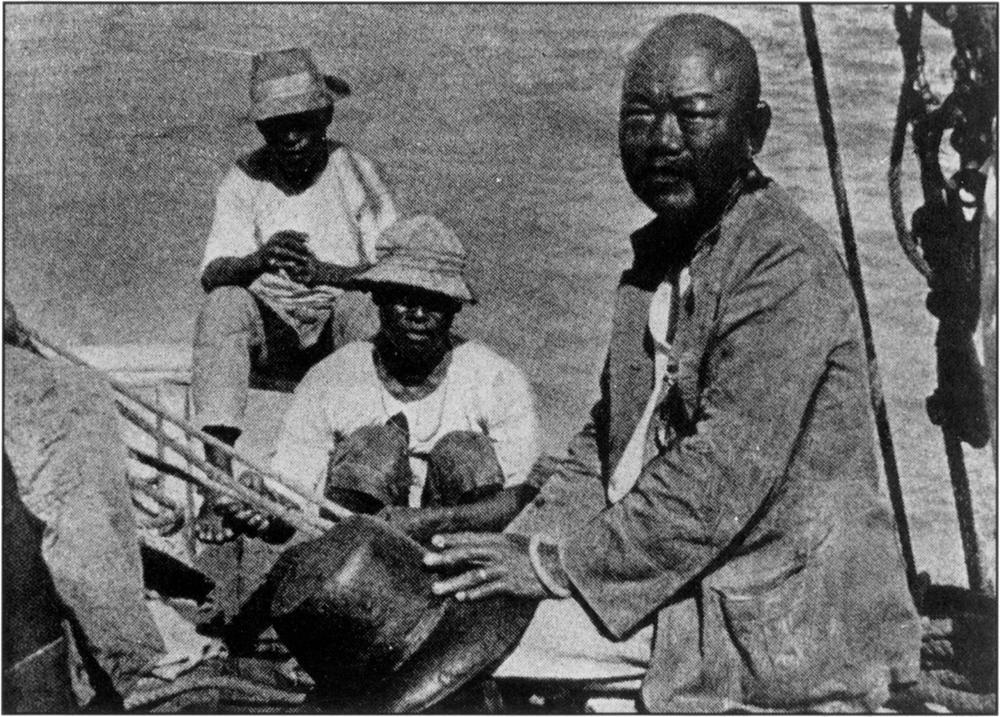

Alder provides a fascinating description of his encounter with two Chinese plume hunters and their party. This probably took place in a coastal village west of the mouth of the Bian River.22 Alder and his companions were waiting for a copra boat to come along the coast (Plates 27 and 28). Their boat, the Nautilus, had been wrecked in the vicinity. While they were waiting, two Chinese hunters and their party of Moresby men stopped at the village. The hunters were tired after making their way to the coast. After a rest, they planned to travel along the coast to Merauke, where they would sell the bird of paradise skins they had taken. Alder describes the incident as follows:

The Chinese are of the typical trader class and appear prosperous, for their watch-chains are very heavy and pure gold – not the red gold we know, but the twenty-two-karat metal of the Orient.

Their advent causes a stir in the kampong [village], for the moment the dogs give warning of the approach of strangers the natives all dive into the shacks, to peer furtively through the crevices until assured the visitors mean them no harm. The Chinese enter the kampong boldly and, espying our camp, come to greet us immediately; and as the Chinaman is always hail fellow well met, we invite the men in and give them a cup of tea …

They seem much surprised to find two white men here and question us regarding the purpose of our visit, thinking at first, doubtless, that we are on the 181same errand as they. They cannot comprehend how we two Americans can find recreation and amusement in coming to this Godforsaken spot, putting up with untold hardship and inconvenience merely to meet and study the lives of the Kia Kia … The Chinese is first, last, and always a business man and bends all his energies towards succeeding in his business. The Moresby boys immediately take up their abode with … the crew of the Nautilus, who are camped near the kampong, and we make the Chinese comfortable in a spare tent, where they spread their mats and prepare to stay a day or two to rest.

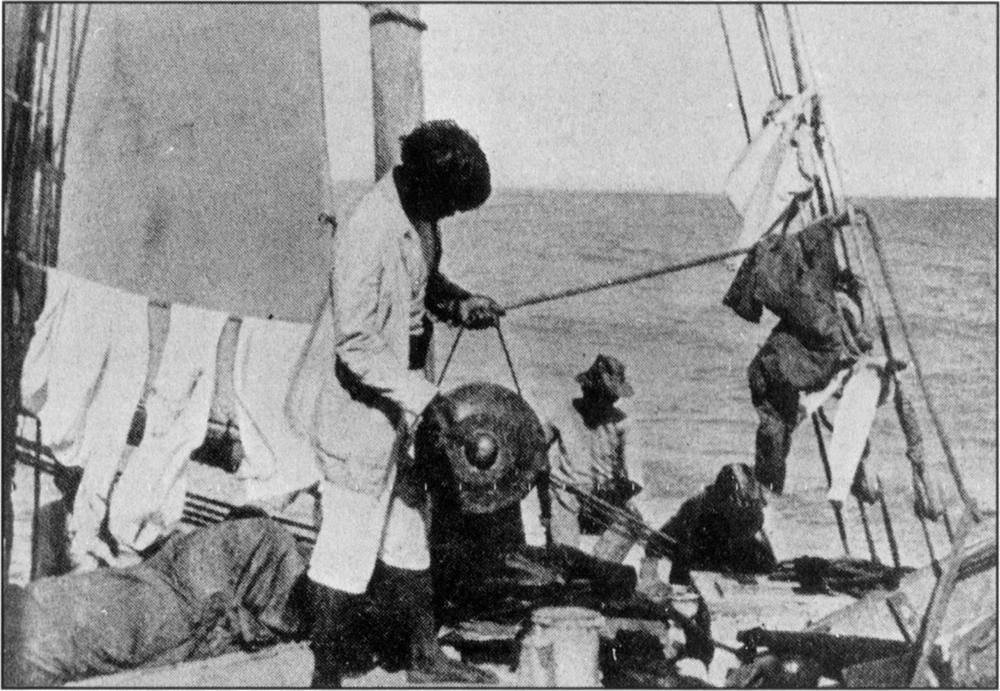

Plate 27: Chinese trader collecting copra along the Merauke coast.

Source: Alder 1922.

Plate 28: Prayers on the Chinese trade boat were accompanied by gong beats.

Source: Adler 1922.

They have been successful in their hunting and have nearly 60 codies, or 1821,200 skins, though they have been in the interior only since last May. The skins, well preserved in arsenic, are done up in parcels. There is a small fortune in the proceeds of their season’s hunting and they are most happy at their success, though they of course do not boast of it …

In the course of the evening our visitors tell us in perfect Malay – they speak only a word of two of English – of the manner of hunting their beautiful quarry. The habits of the birds are most interesting. They also tell us something which is news to us. We had supposed that the restrictions placed upon the importation of the skins into America23 were due to the possibility of the species becoming extinct, but the hunters tell us that is not the case. They say that only the male birds in full plumage are taken and that the bird never attains his fullest plumage until after the second bird-mating season. This being the case, it would seem that there is no danger of extinction, and the Chinese seemed to think that the ruling was unjust.

The method of hunting the birds is odd and requires much patience. When the locality they frequent is located, a search is made for the dancing-tree. This is usually an immense bare-limbed tree that towers above the surrounding jungle. When such a tree is found it is watched for several mornings to see if the birds come to it, and if this is the case, a blind is constructed well up in its branches where the hunters can hide from the sight of the birds but are within easy bow-shot of them. Two bowmen will ascend to this masking shelter, two or three hours before dawn, and lie in wait for the birds that they know will come with the first rays of the rising sun.

The trees surrounding the large one fill with female birds, come to witness the dancing of the males who strut and dance on the bare branches of the large tree. The hunters lie in wait in their blind until the tree is literally filled with the gorgeous male birds.

The birds become so engrossed in their strutting and vain showing-off to the females that the hunters are able to shoot them down one by one with the blunt arrows used for this purpose. The large round ends of the arrows merely stun the birds, which fall to the ground and are picked up by the men below.

Frequently the hunters are able to kill two thirds of the birds before the others take alarm and fly away. The skins, as they are gathered, are washed in arsenic soap and packed away in bundles of twenty. The washing shrinks a skin so that the true proportions of the bird are lost: the head is large in relation to the rest of the body, but with the removal of the skull it shrinks to such an extent that it seems to be exceedingly small.

The skin is taken for the gorgeous plumes which spring from the side of the bird and are best seen on the live bird when he is strutting or in flight. It is a matter of interest that the nests of the birds, and consequently their eggs, are never24 found, and large prices have been offered for a specimen of each. Among the hunters there seems to be a general belief that only one bird is reared at a time, though this is only conjecture.

183On the morrow the hunters gather some surf-fish as a welcome change in their diet and, after smoking these a little and drying them after the Chinese fashion, depart on the last long leg of their trip to Merauke. We tell them in response to their invitation to accompany them that we are quite content here and will await the coming of the next trading Malay [Indonesian] who happens along.25

The administration of Dutch New Guinea imposed a hunting season in response to the demands of conservationists. According to J.W. Schoorl,26 a former government officer, this extended from April to September.27 This did not inconvenience plume hunters as they were not interested in hunting beyond this season for two reasons. First of all, there was little point as the birds were not in plumage. Secondly, life would have been even more unpleasant. From about May to October the steady southeast trade wind brings fairly dry and cool air. This gradually dries up the flooded swamplands which are inundated during January to April by the heavy squalls of the northwest monsoon.28 Only government patrols tended to venture out in the northwest monsoon.

Many individuals came and braved the inhospitable countryside and virtually unknown inhabitants for the quick profits that could be gained from plumes. The occupation of plume hunter attracted some tough characters. Many got on well with the locals, but others had few moral scruples and antagonised them, and some died in pay-back killings.

A.K. Nielsen, a Danish visitor to the Merauke area in the late 1920s, makes the following comments about the relations that existed between the plume hunters and the local people. His statement on this topic is extracted in full as it catches some of the atmosphere of the period:

Plume hunting was a life filled with exhaustion and danger. Despite the presence of the daily glowing tropical sun, the nightly mosquitoes, ant swarms and the deadly tropical diseases lying in wait in the swampland, the greatest danger remained in the battle with the locals, who saw every stranger who penetrated into their hunting grounds as an enemy … The bird hunters themselves were rough fellows who did not have much conscience when it came to collecting birds of paradise. Some barely knew the traditions nor the way the locals reasoned, others did not take these into account at all. In their eyes the jungle was a no-man’s-land where anyone could shoot where he visited.

Under Kaja-Kaja law, each bird, animal and tree in the jungle which had any value belonged to the tribe or to the village. Any stranger, whether he be white or from another tribe, who did not respect these rights had to be prepared to be treated as an enemy.

184Most important of all were the birds of paradise and the specific trees to which they returned every year. These trees were tabooed. The hunters could only obtain the right to shoot the birds in these trees by either a friendly agreement or by the payment of a given amount per bird to the tribe who collectively owned the hunting area. Many a bloody tragedy occurred between the locals and bird hunters because these unwritten laws of the jungle were not respected …

When bird hunters subsequently contact Kaja-Kaja belonging to tribes who had been involved in [killing bird of paradise hunters], there was a merciless revenge. The arm of Dutch authority was too weak and did not extend far enough to exert any meaningful control in these isolated, unexplored regions. It was the bird hunters or the Kaja-Kaja’s, depending on which group was the strongest, who judged and punished when a crime was committed.29

Local accounts of relations between villagers and hunters are generally negative in the Middle Fly. Two such accounts come from members of the Wamek and Sanggizi tribes of the Boazi speakers of the Middle Fly. The Wamek relate an incident which involved their parents and grandparents, and European hunters near the headwaters of Kongun Lake (Figure 38). Being unfamiliar with Europeans, they mistook them for ghosts on the basis of their light skins, beards and long hair, and fled in horror. The disconcerted Europeans responded by indiscriminately shooting at them, and as a result a number of men, women and children were killed. Those that survived never forgot this incident and presumably initiated their own indiscriminate retaliations against plume hunters. This probably explains why most Wamek accounts of bird of paradise hunters end with hunters shooting and killing at least one Wamek.30

In another incident a man from the Sanggizi tribe saw some Indonesian bird hunters pass by his bush fowl hide. He quickly returned to his village on an island in the middle of Kai Lagoon (Figure 38) to alert his people. Soon afterwards five Indonesian hunters and a man from a Marind-anim village near Merauke arrived on the shore of the lagoon and indicated that they wanted to make friendly contact. The Sanggizi took the hunters to their village. The hunters then showed the villagers how guns worked and asked if they wanted knives, axes and food. They were then offered gifts of trade goods. The Sanggizi accepted some trade tobacco, found salt and sugar to their taste, but being unused to the texture of rice and biscuits found them unpalatable. It was then explained that the hunters wanted to exchange these goods for birds of paradise. Concerned that the hunters might shoot all the birds of paradise on their land the Sanggizi decided to kill the hunters. Only the Merauke man managed to escape.31

185By contrast the Muyu, Yonggom, Ningerum and Awin who live further inland generally speak more positively of their relations with bird hunters (see Muyu and Ok Tedi case studies below).

Some insights into the attitudes of those Europeans who chose to become plume hunters and traders is provided by the statements of a European plume trader called Reache. He entertained his drinking companions in Merauke with tales about his exploits as a bird of paradise trader. His account went as follows:

You fellows know, I guess, what I’m here for. It’s paradise. Not the country, no! The country is hell and no mistake, but the birds – that is what I go after, and get, too. I outfitted in Moresby32 and when I got my hunters together and plenty of petrol for the launch I headed for the upper [Digul]. It’s way up in the interior where we get the best birds. It’s bad country up there … The governor warned me that I was taking my life in my hands, but I don’t know any one else’s hands I’d rather have it in, so I went inside. My crew of hunters was as ripe a gang of cut-throats as one would wish to see and they tried cutting a few didoes among themselves, but after I’d knocked a couple cold they took to behaving and I let things go at that.

You want a gang like that for hard going. They’re necessary. The only way to keep them happy is to give them plenty of work or, what they like best, plenty of scrapping. Then they haven’t time to brood over differences of opinion amongst themselves. I loaded up a couple of bushels of [baler] shells [which the men wore as pubic coverings] … Well, I use those shells for currency. One first-class shell which costs me about 10 cents Dutch money buys a bird of paradise skin that is worth 1200 guilders a cody, that is, 20 skins – or, as it figures out in real money, 40 dollars [worth of skins]. It’s a fair margin of profit …

Well, … we went inside – I, seven shooters, and some other Moresby boys for packers. Soon we had all the shooting and trading we wanted. Everything went all right for a time and there was no trouble with the natives. I gave them one nice shiny shell for one prime skin and they were as pleased as possible.

Some Chinese hunters were also operating in the vicinity. They were attacked and killed after they came into conflict with the local people. After this incident one of Reache’s crew members took exception to a villager dressed in Chinese trousers trying to sell him bird of paradise skins. He killed the villager and this led to a fight from which only Reache and his launch-operator survived.33

In the Mapi (Mappi) River area (Figure 38), the Jaqaj indicated to J.H.M.C. Boelaars34 many places deep in the interior where bird hunters had been killed. The most famous incident was on the Dutch and Papuan border and involved two Australians called Dreschler and Bell. 186The investigation of this incident by a joint Australian and Dutch patrol towards the end of 1920 is described in the Middle Fly section below.

Plume hunters and traders were speculators. They clearly profited during the plume boom, but they became victims of their own greed when prices plunged downwards. The recorded comments of the old Irish bird hunter, who settled at Merauke after plume hunting became illegal in most of Dutch New Guinea in 1924, clearly illustrate this point:

After many dangers the exhausted hunters returned to Merauke with their precious booty. There they had to face the surprise and emotion each time of learning what price their birds of paradise would fetch. No one could predict what variations would occur on the world market. The Irishman had experienced all the possible vagaries of the market. He told me of the exciting days when the prices increased from week to week. The hunters obtained £5 for one bird which cost them one knife, worth a shilling, and the same birds were later offered for £15–20 in the fashion magazines of London and Paris. In that year some 25,000 birds of paradise were exported from Merauke. They had a value of 2–2,500,000 kronen.

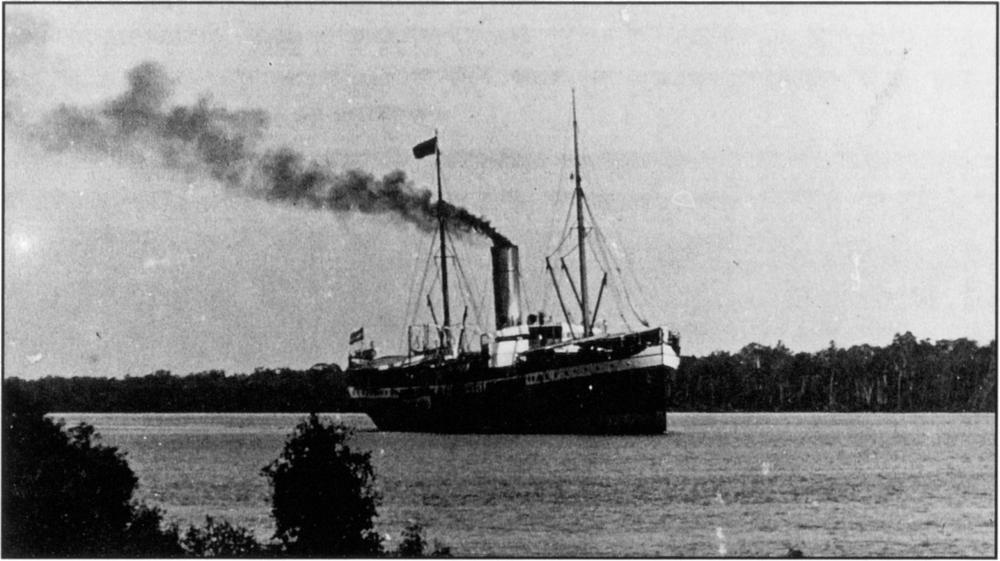

He also experienced the shock of learning that World War I had broken out. This news was brought to Merauke by mail boat [see Plate 29]. In those days there was still no radio station on New Guinea. The people there were totally isolated from world news. Even as the ship was sailing into the harbour, buyers were still bidding £78 for each set of birds; the Chinese who ruled the market asked £80. As soon as the news of the outbreak of war reached those on land, hunters could not get more than £1 for 20 birds. Many bird traders were ruined in just a few minutes. Large fortunes melted away like snow in the sun.35

Plate 29: Mail boat coming into Merauke before World War I. On shore there would be anxious speculation over the current price of bird of paradise skins and last-minute transactions.

Photo: Courtesy of Photo Archives, Rijksmuseum voor Volkenkunde, Leiden, The Netherlands.

187The plume boom began in 1908 and continued until the outbreak of World War I in August 1914. It resumed again after the war. After hunting resumed, the Dutch administration made a number of punitive expeditions against groups who had killed plume hunters working in their areas. To monitor the activities of plume hunters and to gain more control over local groups two new government stations were established: Torai on the upper Maro (Merauke) River in 1918 and Assike on the Digul in 1919 (Figure 38). Assike was strategically located 290 kilometres up the Digul River, just south of where the Kao River forks northeastwards.36

When Leo Austen, a patrol officer from Papua, visited Assike in 1922 he reported that there were houses for Keyzer, the officer-in-charge, and Veelenturf, the police master. The barracks, gaol and quarters for seamen and others were made of local materials. In addition to van Grunungen, the European merchant established at Assike, there were several Chinese stores. To Austen’s amazement these contained everything one could want for sale, and at prices cheaper than could be found at either Daru or Port Moresby. A steamer came up the Digul to Assike once a month from Merauke to bring passengers and supplies and to take out plumes.37

The vast area within which the plume hunters operated made it an impossible task to oversee their activities. However, it appears that Keyzer, the officer-in-charge at Assike, did record the proposed routes of hunting expeditions in his area.38 Some hunters also sent him details of their progress. He went out on patrols up-river, not only to the Muyu area but also to the country of the upper Digul to the west. South of Assike he was familiar with the rivers, countryside and people almost down to Merauke.

Keyzer had been instructed to prevent clashes and to punish any acts of violence. His superior was a long way from Assike at Taul in the Kei Islands.39 He was probably unaware that Keyzer was affected by ‘bird of paradise fever’. It is said that Keyzer earned some 500,000 kronen in one year alone. This income suggests that his surveillance patrols were used as an opportunity to shoot birds of paradise.40 No wonder Leo Austen,41 the patrol officer from Papua, commented that most of the plume hunters entering Papua were probably the Dutch police themselves. Despite the fortune Keyzer made from plumes, he never left Assike. At the end of 1922 he died from swamp fever and was buried in the graveyard there. His companions include 40 police soldiers who also died from swamp fever.42 Assike was closed after Keyzer’s death and Torai was closed in 1924.

By the late 1920s there was no market for bird of paradise plumes. Merauke like Hollandia (Jayapura) had become a sleepy settlement. 188Nielsen personally observed the aftermath of the plume boom in Merauke.

These days no one is interested in birds of paradise, consequently Merauke is now peaceful and quiet. In the tin trunks of the Chinese buyers lie thousands of birds that cannot be sold, they are preserved by means of camphor, awaiting better days. In the primeval forest, the male birds are now able to dance undisturbed and show off their feathered glory.

The knives and axes the Kaja-Kaja’s obtained for their birds have long become blunt and the tobacco has all been smoked. Both have disappeared, the same is true of the millions in currency which had flooded into the country, thanks to the golden, feathered glory. The bird hunters have gone. Many died here, the rest have been attracted to new regions in search of luck. None of them became rich, despite their exertions, the danger, and the fortunes which passed through their hands.43

The species hunted and where they were sought

During the European plume boom, the Merauke and Mimika areas44 became new sources of the Greater Bird of Paradise (Paradisaea apoda). In the 1920s the Raggiana Bird of Paradise was scarce in Dutch New Guinea, but was common over the border in Papua.45 Today in the Middle Fly this species is only found in the ridge forests north of Kongun Lake and Lake Murray (Figure 38).46 Although plume hunting was prohibited in Papua in 1908, this did not daunt plume hunters seeking Raggiana from entering the upper and middle reaches of the Fly River system. Like their counterparts who crossed into German New Guinea from Hollandia without hunting permits, these hunters were able to break existing laws by operating in inland areas far beyond any government surveillance.

Before 1909–1910, the Raggiana Bird of Paradise was rarely seen at European plume markets. It then became quite common,47 presumably because of exports from Merauke, as well as German New Guinea, which later became the Mandated Territory of New Guinea. In 1920 an export ordinance was passed in the Mandated Territory which restricted the export of plumes and by 1922 they were illegal exports. This meant that from 1920 the border area of Papua became the only source of Raggiana, and explains why the chance of acquiring some red Raggiana plumes tempted a group of Chinese and Ambonese traders to stop at the Kaiakaia camp (Figure 41). There they found evidence that some European plume hunters might have been murdered.48 This was the beginning of the Dreschler and Bell case described below.

In their search for plumes, hunters travelled to the lower foothills of the central mountain chain. At times they crossed watersheds and 189continued their expeditions by local canoes. They are known to have travelled up the many branches of the upper Digul. Of these the Muyu tributary was one of their favoured areas. From there they visited the country drained by the Ok Tedi and returned to Merauke via the Fly, upper Maro and Bian Rivers (Figure 38).

Figure 41: The upper reaches of the Fly and Digul River systems showing the tracks used by bird of paradise hunters. Also shown are indications of Indonesian hunters observed by Leo Austen along the Ok Tedi.

190In their travels to and from Merauke plume hunters often travelled on similar routes to those taken previously by Marind-anim raiders,49 for example, via the Bian River and then overland to Assike or the Fly River. Another important route from Merauke was along the coast to Okaba, then overland to the Digul. This was presumably the route taken by the Chinese hunters and their Motuan assistants described by W.F. Alder, cited above. When returning after working far inland, many hunters without motor boats followed this route. They floated down the Digul River on rafts and landed directly north of Okaba. They walked to Okaba and then along the coast to Koembe. From Koembe they travelled by motor boat to Merauke.50, 51

Three regional studies

The Muyu, Middle Fly and Ok Tedi areas are each discussed below. The studies cover what is known in each case about the activities of plume hunters, the local reception they received and their impact on the local people.

The Muyu

The Muyu live in undulating forest-covered country. Their area became one of the main sources of plumes in the Merauke region during the European plume boom. According to the Muyu, the first foreigners just came up and returned down the Kao River (Figure 41) in a house placed on top of a boat. Some time afterwards, plume hunters came seeking birds of paradise. Government records reveal that the first military patrol up the Kao River was in 1909, whereas plume hunters only began working the area in 1914. Some hunters went to the upper Muyu River in small motor boats.

Some of the first plume hunters to enter the Muyu area received a hostile barrage of arrows. This was mainly because the Muyu thought they were spirits. When the Muyu realised that they were dealing with real people, who could provide them with useful items, their attitudes changed. Friendly relations were then established by gifts of tobacco and other goods.

The Muyu assisted the plume hunters when it became known that these people were after birds of paradise. In exchange for plumes and the rights to shoot the birds, the Muyu received axes, chopping knives and clothing. Some Muyu men became guides and interpreters and 191accompanied the hunters on trips throughout the Muyu area and beyond. For example, some crossed into Papua and went east of the Ok Tedi.

Those who learnt how to use guns also helped with hunting. This cooperation was further encouraged by the Dutch regulation which required hunters to employ local assistants. The hunters were also expected by law to pay the owner of the land where a display tree was located before any birds were shot.

The Muyu soon found that there were good and bad hunters. They claim they never killed a plume hunter unless he did something wrong. Food thefts seem to have been the main offence. Two Indonesians and their Muyu guide were killed and eaten at Tembutkim because they had stolen food from an associated settlement; but later another Indonesian and other Muyu avenged their deaths. The Australian who climbed Bombin Mountain in the upper foothills was probably also killed for stealing food. For their part, the Muyu never hesitated to steal the possessions of plume hunters if they had the opportunity. They also used plume hunters to kill their personal enemies. For example, a Yibi man apparently persuaded a hunter to shoot a Katanam man who had murdered his father.

Plume hunters introduced the Muyu to the Malay language and foreign goods and also made them aware of places beyond their borders. Some of them trusted these strangers enough to go with them to other areas. Those who went to Merauke learnt about the foreigner’s world by seeing it for themselves. When Muyu youths arrived at Merauke wharf, the police usually took them away from the plume hunters and put them in mission school. In this way they not only came to know about schools and towns, but also something about the behaviour of different foreigners. When they returned home, these youths told stories about their observations and adventures, which made others who had not travelled also aware of the outside world. Later many men who had gained outside experience in their youth became village headmen or their assistants.

When the plume trade ceased in the Muyu area in 1926, the Muyu found themselves without a source of foreign goods. The plume hunters came no more. They began to look for new sources of supply. Some Muyu went to the government post at Tanah Merah which was established in 1926 (Figures 38 and 41). There they either sold their produce or worked for officials or internees at the adjacent Boven Digul internment camp. Others moved south towards Muting (Figure 38) where there were Chinese traders. A government station was opened at Muting in 1924 and a mission in 1930.52192

The Middle Fly

When Sir William MacGregor returned from his December 1889 to February 1890 expedition up the Fly, he recommended that future government patrols should be made in the months of June or July. This would allow information about the conditions during the southeast season to be recorded, and since this was the time the birds were in full plumage, some could be collected for scientific purposes.53 Unfortunately this suggestion was ignored. Throughout the period when bird of paradise plumes were sought for European plume markets, no Papuan government patrols were made when the birds were in full plumage; see Table 12. Thus there are no first hand historical documents which describe the activities of plume hunters in the Fly region of Papua. The only recorded information on the activities of plume hunters on the Middle Fly resulted from the joint Australian and Dutch investigation of the alleged murder of two plume hunters in the area.54

Table 12: Official and scientific expeditions to the middle and upper Fly from 1875 to 1926

| expedition leader | date | purpose of trip |

|---|---|---|

| L.M. D’Albertis | 1875 | exploration |

| L.M. D’Albertis | 1876 | exploration |

| Captain Everill | 1885 | exploration |

| Sir William MacGregor | 1889 Dec 26–1890 Feb 4 | exploration |

| Baker & Burrows | 1913 | exploration |

| J.H.P. Murray | 1914 Mar 27–1914 Apr 18 | exploration |

| Captain Frank Hurley | 1914 | exploration |

| Sir Rupert Clarke | 1914 | exploration |

| A.P. Lyons & Leo Austen | 1920 Oct 24–1920 Dec 16 | investigate alleged murders |

| Leo Austen | 1922 Jan 12–1922 Apr 5 | investigate alleged murders |

| Leo Austen | 1922 Oct 16–1922 Nov 14 | investigate alleged murders |

Sources

Based on Austen 1923a, 1925; D’Albertis 1880; Everill 1888; Goode 1977; Hurley 1924; Lyons 1922; MacGregor 1889–1890; Murray 1914; personal communication Michael Quinnell 1983, see footnote 54.

193When the Dutch came they discouraged raiding. This allowed Chinese traders to become established at Torai and in the Muting area (Figure 38). The Bian Marind then found it to their advantage to make peace with the Boazi of the Middle Fly (Figure 41).55 A major factor behind this peace treaty was probably the presence of the highly desired Raggiana Bird of Paradise in the forests on the ridges north of Lake Murray in the Middle Fly. The red plumes of this species would have commanded a high value with the Chinese trade store owners at Muting. From this time on Chinese and other plume hunters with Bian Marind guides would have been entering this area via the upper Bian.

An increasing familiarity with traders and hunters probably explains why on two occasions men on the banks of the Fly River made the motion of cutting or chopping when they saw J.H.P. Murray’s expedition going up the Fly in April 1914. One incident was some 15 kilometres north of where the Fly extends the international border westwards and the other was some 45 kilometres upriver from Everill Junction (Figure 38).56

By early 1914 the interests and activities of plume hunters were widely known. The trade goods they brought with them were also appreciated. In 1913 an overland journey was made by a Dutch military patrol from the Kao to the Fly at the northern end of where it bulges west at the international border (Figure 38). On their way to the Fly a trade axe was left at a settlement where the people were very apprehensive of their presence. When the same patrol passed through the settlement on their return, one man offered them a bird of paradise headdress, with the apparent intention of exchanging it.57

When trade goods were left at base camps and appeared to be abandoned, the chance was not wasted. When Murray in 1913 visited the base camp established the year before by Baker and Burrows near Everill Junction, he found that tomahawks and other goods had been stolen. The only item not stolen was the stick tobacco.58 The case had been opened but the contents were presumably considered inferior to the local product.

After the First World War, bird hunters from Dutch territory were keen to hunt the Raggiana Bird of Paradise found across the border in Papua. This was illegal, but profitable. There were a number of ways to reach the Fly. For instance, it was possible to go overland and via channels and small lakes from the Bian River (Figure 38). This took two days.59 Alternatively they could go overland from Assike, the Kao River or the Muyu River. These routes took a great deal longer. The shortest walk was from the upper Muyu to the Ok Birim, a tributary of the Ok Tedi which flows into the Fly (Figure 41).

194Some bird of paradise hunters lost their lives, but we know little about these incidents. Those killed include Europeans such as Penrode and a number of Indonesians. A Timorese hunter was killed in the Ok Tedi (Alice River) in 1920.60 Some of the bodies that were recovered were buried at Merauke.61 Other hunters were lucky enough to escape. This was the good fortune of a party of Chinese hunters who were attacked in the headwaters area of the Maro (Merauke), Bian and Kumbe Rivers (Figure 38).62

In late 1920 some Chinese and Ambonese plume traders reported to the Dutch authorities that some Europeans had probably been murdered on the Australian side of the Fly at its most westerly extension into Dutch territory. A joint Dutch and Australian patrol was then made to investigate the alleged murder of two Europeans called Dreschler and Bell and the rest of their party.

The Chinese and Ambonese plume traders had reached the Fly by a creek accessible overland from the headwaters of the Bian River (Figure 38). Their Bian guides had obtained two canoes which they used to travel down a stream which in half an hour brought them to the Fly. The Chinese claimed they thought they were on a branch of the Bian.63 However, the Papuan Resident Magistrate A.P. Lyons clearly understood their strange loss of geographic sense. The Chinese could not admit to knowing their true whereabouts, as this would make them guilty of illegally collecting and shooting birds in Papua.

Kaiakaia Camp was the name the patrol gave to a burnt-down village on the most westerly bend of the Fly River (Figure 41). The village had extended for about 800 metres along the river’s edge and was divided into two parts. These were separated by a scrub-covered area. They not only found the remains of traditional-style buildings but also a house with certain European features. These included two slab bunks and a fireplace which had forked supports for hanging billycans by means of a horizontal bar. Nearby were tins and bottles, a rough baking dish made from a kerosene can and the remains of a newspaper called the American Exporter. In another part of the village they found a human jaw with two metal-filled teeth,64 brass caps from a Remington repeater, Winchester shot cartridges, an old tin, a cardboard cartridge box, a broken leather sheath for a knife and steel, and a broken glass bottle. The whole village appeared as if it had been wantonly ransacked and burnt. In the lagoon behind the village they found four canoes which had been damaged beyond repair by cuts from steel axes.65

The village had not been destroyed when the Chinese and Ambonese traders had stopped at the settlement after being offered Raggiana plumes. However they had fled once they had seen a human jaw which had teeth with metal fillings, shirts bearing Bell’s name and 195had obtained a book. The writing inside this book was later identified as Bell’s.66

Another camp was found several kilometres from the Kaiakaia Camp at the southern end of the lagoon on the Dutch side of the Fly. Two cognac bottles of the brand drunk by Dreschler and other indications of European habitation were found. Leo Austen, now Assistant Resident Magistrate at Daru, found further items on a subsequent patrol made in 1922. These finds were made at a new settlement which was abandoned when his patrol approached. Austen called the settlement Bamboo Creek, now probably known as Binge Creek,67 see Figures 38 and 41. There he found Bell’s pocket-book, several photographs, a 300 guilder note, a sock, an enamel pannikin, a reel of cotton and two or three empty bottles.68

It is possible that other plume hunters attacked and ransacked the village when they discovered that Dreschler and Bell had been killed. Another house with certain European features was found a short distance further up the Fly in 1920. It was located near a sago swamp on the west bank not far from Slade Island. There were two rough bunks and a fireplace with forked sticks and the walls had rifle-fire loop holes. No tins or bottles were found.69

Unfortunately the local story is not known. In retrospect it is strange that the Dutch did not take a Bian Marind or Marind speaker on the joint expedition made to investigate the deaths of Dreschler, Bell and other members of their plume-hunting party. The Dutch officials had apparently assumed that the Ok Tedi people were responsible, as they had recently killed a Timorese hunter.

The Sydney Morning Herald70 provides further information about Dreschler and Bell. Dreschler was a well-known trader. He was 30 years old, married, with a home in Melbourne. Bell was 26 and had run a store in Port Moresby until the outbreak of the First World War. He then returned to Sydney to enlist. Bell served in France with the Light Trench Mortar Brigade where he was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal, gained a lieutenancy and then joined the First Artilleiy Brigade. He returned to Australia in August 1919 and sailed with Dreschler for New Guinea in March 1920. Bell was to have returned to Sydney in October that year to be married.

Bell and Dreschler were apparently part of a larger party, most of whom returned to Merauke, leaving Bell and Dreschler to go further inland with eight New Guinean assistants. These ten men presumably perished at Kaiakaia Camp. The larger party of nineteen New Guineans was led by Rosenhain. He was related to the firm of Rosenhain and Company based in Sydney, which had an agency in Surabaya and trading stations in Dutch New Guinea.196

The Ok Tedi

During the joint Australian–Dutch patrol the Australians learnt from a Dutch interpreter from Muyu (Muiu) River that a supposedly large population lived in the vicinity of the Ok Tedi. Leo Austen’s subsequent patrols were concerned with checking this claim. People from villages located on the west bank of the lower Ok Tedi told Austen that Indonesian plume traders came to their area each year. These foreigners not only shot on their land, but they also crossed over to the east bank in their search for plumes. Later in his patrol, Austen observed a number of plume hunters’ camp sites in Awin (Aekyom) territory east of the Ok Tedi. These shelters had been built at different points along the main walking tracks; see Figure 41.71 According to present-day Awin informants, the hunters usually built temporary shelters in the vicinity of the Awin garden hamlets and stayed for a day or two to trade for plumes.72 On the night of the 26th of February 1922, Austen’s patrol spent the night in one of these abandoned camps.

Plume hunters also ventured up and east of the Ok Mart. When sighting Austen’s patrol, the people on the lower reaches of this river had assumed that these foreigners were also going upriver to shoot birds.73 Present-day Awin claim that the hunters penetrated as far north as the vicinity of Tmansawenai village on the upper Fly near the foothills of the Victor Emanuel Range. Further south they went as far east as the present-day location of Drimdemesuk village which is south of the Fly-Elevala junction.74 This suggests that few hunters crossed to the eastern banks of the upper Fly River.

When the Yonggom-speaking Or villagers heard gunshots, some went to Austen’s camp at Wukpit expecting to find plume hunters. The Awin seen by the patrol were very timid and all their villages were deserted. From this Austen concluded that they had recently had trouble with plume hunters. Another explanation might be that plume hunters had only recently expanded their activities across the Ok Tedi in search of cheaper plumes. The villagers also told Austen through interpreters that the plume hunters did not pay them enough. Since the Muyu had trade relations with the Awin,75 they were probably aware that they were receiving far less payment than the people further west. It was the practice of plume traders to keep their payments as low as possible.

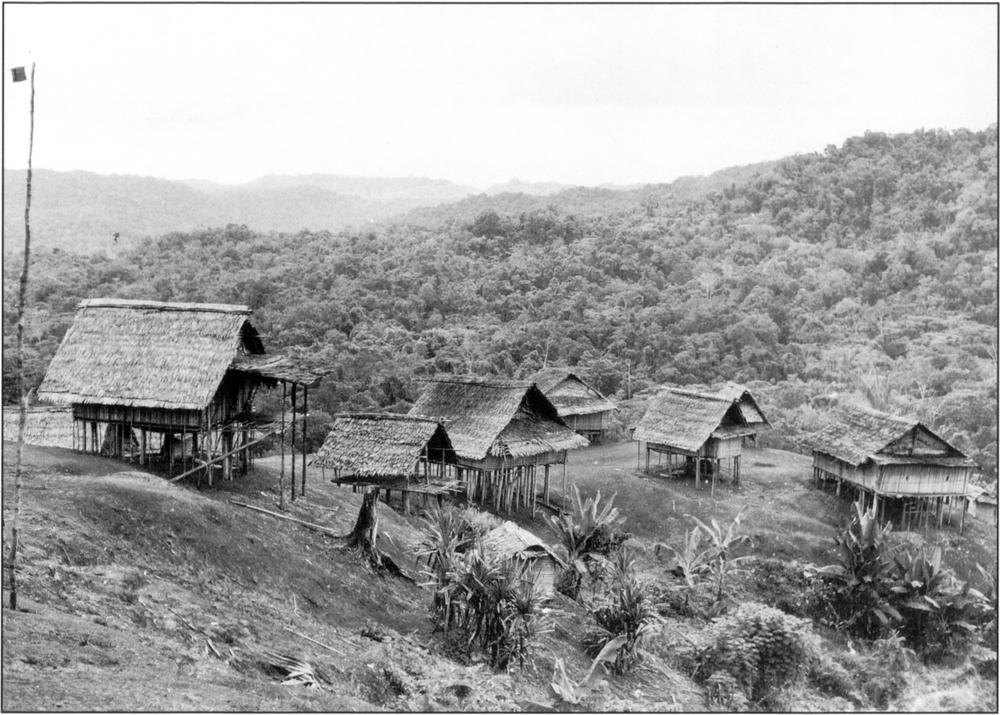

Austen observed that the Awin had received knives, tomahawks and trade beads from the plume hunters. There was also a northward movement of trade goods from the south. A Yonggom (Iongom) man from Namangor village joined Austen’s patrol as an interpreter. He took along a metal axe that he wished to trade with the Ningerum.76 A northern Ningerum settlement is shown in Plate 30.197

Plate 30: Derongo, a Ningerum settlement, in 1966.

Photo: Courtesy of H. Bell. PNG National Museum Files.

The Ningerum Austen met near and north of his Observation Hill, see Figure 41, had some trade items and a limited knowledge of certain Malay words. They had metal axes, as cuts made by iron axes as well as stone axes were seen along the track. They were terribly keen to obtain kapak, which is the Malay word for axe, but were not interested in knives until it was demonstrated how they could cut wood. They then immediately recognised these implements as karanang, the Malay word for large knife. Presumably they had heard about these from the Muyu or other Ningerum. but had never seen them. Austen certainly doubted whether they had seen an Indonesian. Although they knew some Malay words, the errors they made seemed to suggest that they had learned the words by hearsay.

Austen’s observations in the upper Ok Tedi suggest that no hunters had actually ventured into that area and that trade goods were only beginning to reach these people. The people in the hamlet he visited near the Moyansil suspension bridge across the Ok Tedi some 5 kilometres southeast of Tabubil had only one iron axe 198(kapak). It had reached them via their trade links with the southwest and they claimed that they were the only people in the vicinity who possessed one. They had never seen knives and did not know the word karanang (knife). When given a knife, a man used the back rather than the sharp side of the knife to cut taro.77 Further up the Ok Tedi, Austen met a man who had never seen an iron axe before but strangely knew “many words of the trade language,78 but mixed them up so much that it was difficult to get what he was driving at.”79 Perhaps when he was on a trading expedition to the Muyu area, he had heard Indonesian traders talking to the Muyu or had been told some words by his Muyu trade partners.

In the mountain foothills Austen experienced the problems plume hunters would have faced in their search for high-altitude bird of paradise species. North of Observation Hill he arranged to purchase some taros and bananas from the local people. From Austen’s point of view he paid a high price and only gained enough to give his 32 man patrol one meal.80 The local people were keen to acquire more axes and knives but were not in a position to provide any more food. It would seem that they had none to spare.81 The upper range of most bird of paradise hunting expeditions was probably the northern extent of where sago was the main staple. It was probably their mainstay, as it would have been impossible for them to have carried enough provisions. This would also explain why the hunters’ house was located near a sago swamp near Slade Island. It may also help to explain the deaths of Dreschler and Bell if they were working sago without permission.

Trade goods obtained from plume hunters were traded on beyond their area of activity. Some were probably traded via the Faiwolmin, others may have been taken back by Tifalmin or perhaps even Telefolmin trading expeditions. When Keyzer was in the upper Muyu area in the early 1920s, he met a party of traders who had come from the headwaters of the Sepik some four days’ walk away. This was probably how a Telefolmin man, observed by Ivan Champion, had acquired two large white beads to wear in his beard.82

Plume hunters and venereal disease

In an attempt to eradicate venereal disease, bird hunting was prohibited in the South New Guinea Subdistrict, specifically the Marind-anim area, from October 1922.83 Hunting was allowed to continue in the Digul and Muyu areas. This was part of the effort the Dutch authorities made to control this disease amongst the Marind-anim. Such steps were thought necessary as the Marind-anim were experiencing a sharp drop in their birth rate.84

199After October 1922 a man could only obtain a bird hunting licence to work in the Muyu or Digul areas if he agreed to submit himself for a medical examination. He was then allowed to leave Merauke for his chosen hunting locality. This was done in order to minimise the risk of venereal disease being spread by plume hunters.85

Border crossing by plume hunters

At the time of the Dreschler-Bell investigation, there was presumably an agreement that the Papuan administration would not press charges if the Chinese and Ambonese hunters who reported the incident guided the Australian and Dutch authorities to the scene of the crime. A certain degree of confusion as to the location of the border did not help matters.

Despite the cartographic work done during the Dutch military patrols, there was still in the early 1920s considerable confusion about the position of the border between Dutch New Guinea and Papua in different localities. For instance, in 1922 the Dutch thought the headwaters of the Muyu were in Papua and passed on to the Papuan administration, for approval, the request of Penrose and Jackson for permission to go there in search of minerals. Permission was granted.86 In reality the area was in Dutch territory.

Austen makes no comment in his report published in 1925 on the likelihood that Dreschler, Bell and the rest of their party were hunting in Papua, nor does he make any recommendations about stopping illegal border crossings by plume hunters. However, the Australians must have voiced their objections to the Dutch administration, as the Muyu area was closed to plume hunters in 1926. By then there was little protest from plume hunters as the prices paid for plumes had fallen and the boom was over. The Digul area was closed two years later.87

Notes

1. From November 1884 to September 1888, British New Guinea was a British Protectorate. It became a British colony from 1888 until September 1906, when the Australian government assumed responsibility for the area and renamed it Papua (Joyce 1972: 115–6).

2. The suffix anim in the name Marind-anim means men. The Marind-anim were called Tugeri by the people of southwest Papua (van Baal 1966: 10, 23).

3. Galis 1953–4: 26.

4. van Baal 1966: 23–4; Galis 1953–4: 27; Joyce 1971: 139–41; Wollaston 1912: 223.

5. Galis 1953–4: 41.

2006. van Baal 1966: 707.

7. Pratt 1906: 43–4.

8. Galis 1953–4: 41.

9. van Baal 1966: 691.

10. van Baal 1966: 497.

11. Champion 1966: 4, 18, 101.

12. Militaire exploratie 1920.

13. Schoorl 1957: 129.

14. Galis 1953–4: 41.

15. van Baal 1966: 544; 659–60.

16. Kaiakaia (Kajakaja; Kaiyakaiya) is the Marind-anim word for peace. On meeting a European they would usually say this greeting. The Dutch adopted it as a name for the local population and later also used the term to refer to a native in other parts of Dutch New Guinea (Meek 1913: 209; Thomson 1953: 6; Schoorl 1957: 131).

17. Nielsen 1930: 217.

18. Nielsen 1930: 218.

19. Nielsen (1930: 228) reports hunters bought birds worth £5 for one-shilling knives; Reache quoted by Alder (1922: 21) says for 10 cents Dutch currency he got 40 dollars worth of skins. Note there is a misprint in Alder’s text which reads that each skin was worth $40. This was never the case even in London; see Table 5. In 1917 birds fetched the Chinese traders and hunters 50 florins (Schoorl 1957: 131) or just less than £2 each.

20. The Timorese and Japanese were probably indentured labourers who had completed their contracts as divers in the Torres Strait pearl beds. They had been brought by the Dutch from Japan and the Dutch East Indies (see e.g. Singe 1979: 172). The Ambonese would have come on Dutch government ships from the administrative centre at Ambon. The Catholic mission at Merauke was founded by missionaries from Toeal in the Kei Islands (Wollaston 1912: 225, 257). Contact between these two missions probably explains why Kei islanders were at Merauke.

21. Nielsen 1930: 219–20.

22. W.F. Alder does not provide a map of his travels, but the few geographic features he gives suggest that they sailed west of Merauke. The Bian would have been the large river they passed, before being shipwrecked near a deserted Jesuit mission building probably in the vicinity of Okaba. Alder claims he was shipwrecked 300 miles (483 km) from Merauke (Alder 1922: 74). This is too great a distance, as it would either place him on the mangrove shoreline of Kolopom Island or in the other direction well inside Papua. The copra trading schooner which picked his party up and took them back to Merauke would not have been frequenting either the Papuan or the Kolopom coast.

23. This probably refers to the United States Federal Tariff Act of 1913 which imposed import restrictions on plumage; see Chapter 5.

24. Eggs of birds of paradise are rarely rather than never found.

25. Alder 1922: 167–72.

26. Schoorl 1957: 276.

27. Neilsen (1930: 218) however claims that the season was from May to September, rather than from April.

20128. van Baal 1966: 16–17.

29. Nielsen 1930: 220–1.

30. Busse 1987: 140.

31. Busse 1987: 140-2.

32. As his party was provisioned in Port Moresby, this probably suggests that the incident took place before Assike was established on the Digul in 1919.

33. Alder 1922: 19–25. See also footnote 18.

34. Boelaars 1958: 155.

35. Nielsen 1930: 227–8.

36. Galis 1953-4: 42; Wirz 1922: 11.

37. Lyons 1922: 118, 121; Austen 1923a: 124–5.

38. These records were probably the responsibility of the clerk at Assike. They would contain much information about the movements of plume-hunters. For instance, Keyzer received a letter on the 11th of August 1920 from the ill-fated Dreschler who was then in the Muyu area (Lyons 1922: 118). It is hoped that these records still exist and might one day be found in Dutch government archives.

39. Boelaars 1981: 5.

40. Nielsen 1930: 224.

41. Austen 1925: 36.

42. Nielsen 1930: 224.

43. Nielsen 1930: 228–9.

44. The intervening Asmat area, from the Otakwa River to the mouth of the Digul (Figures 29 and 38), was avoided by plume hunters because of the known hostility of the Asmat towards foreigners (Pratt 1911: 47). Between 1904 and 1913, several Dutch military patrols penetrated the Asmat region, but they were more concerned with gaining access to the enticing snow-covered peaks of the central mountain range than pacifying the local people (Gerbrands 1967a). However it is possible that plume hunters entered the area after World War I. During World War II, Thomson (1953: 3) may have encountered Asmat familiar with the interests of Indonesian bird hunters. A government post had been established at Agats just before World War II in 1938. The post was established because the Mimika complained that they were being attacked by the Asmat. It was closed soon after the war broke out and was not re-established until 1955. The region was then opened up to outsiders and as a consequence Asmat carvings became known throughout the world (Gerbrands 1967a; 1967b).

45. Lyons 1922: 121.

46. Mark Busse personal communication 1992.

47. Downham 1911: 43.

48. Lyons 1922: 114.

49. J. Verschueren, who was a mission worker amongst the Marind-anim, travelled on one of the raiding tracks of the upper Bian in 1953. He was taken from Womod River in the Auyu area down to Mutung. Crossing the Digul by canoe, they entered a small southern tributary. When they had arrived near the springs, the canoes were put away in the brushwood. From there they went on foot through the forest and after four hours’ walk emerged on the bank of a swamp, where after some searching, the guides found a canoe which had been hidden there. Boarding the canoe, they went to Manggis, the southernmost of all the upper Bian villages. The 202path they had followed was a typical kui-kai, a straight, rather broad, cleared passage through the forest, with on either end a hiding place for canoes. If necessary, new canoes would be made on the spot (van Baal 1966: 705).

50. Schoorl 1957: 129–35; Schoorl 1967; Schoorl 1993: 147–53.

51. One advantage of this route was that it avoided the strong tidal currents at the mouth of the Digul and in the Marianne Strait (Figure 38) (van Baal 1966: 707).

52. Schoorl 1957: 133.

53. MacGregor 1889–90: 64.

54. Sir Rupert Clarke who travelled up the Fly into the Awin area in 1914 may have kept a diary, but to date such a document has not been located. His ethnographic collection is held at the Queensland Museum in Brisbane. Since he arrived in Port Moresby in early May from Australia and was consigning his collection for shipment from Port Moresby in January, he would have been in the Fly during the plume-hunting season (Michael Quinnell personal communication 1983).

55. van Baal 1966: 706.

56. Murray 1914: 22, 24.

57. Schoorl 1957: 129–135, 278–9; 1967: 170–1.

58. Murray 1914: 24.

59. Lyons n.d.

60. Lyons 1922: 117; Nielsen 1930: 225.

61. Nielsen 1930: 227.

62. Lyons 1922: 123.

63. Lyons n.d.; 1922: 113.

64. A Sydney dentist identified the gold filling in one of the teeth and confirmed that the jaw belonged to one of the Australians (Nielsen 1930: 225).

65. Lyons 1922: 114–5.

66. Lyons 1922: 118.

67. Mark Busse personal communication 1984.

68. Austen 1923a: 124, 132.

69. Lyons 1922: 116.

70. Anon 1920.

71. Austen 1923a, 1923b, 1925.

72. Depew n.d.

73. Austen 1923a: 131.

74. Depew n.d.

75. Austen actually met some Muyu at the Awin village of Gwembip (Austen 1923a: 128). Schoorl (1957: 11) also confirms that the Muyu knew about and traded with the Awin.

76. Austen 1925: 27–8.

77. Austen 1925: 32, 34.

78. Austen (1925: 36) lists words from the trade language found in the Ok Tedi area.

79. Austen 1925: 33.

80. Hunters primarily concerned with obtaining rare natural history 203specimens rather than millinery plumes would have travelled in a small group. The fact that some collectors were able to obtain some high-altitude species which have a restricted distribution indicates that Indonesian hunters did visit such regions in other parts of Dutch New Guinea.

81. They would have faced the dilemma of whether to obtain tools to improve their future livelihood at the risk of illness and possibly death because of inadequate supplies.

82. Lyons 1922: 118; Champion 1966: 172.

83. Schoorl 1957: 131.

84. van Baal 1966: 25–6.

85. Lyons 1922: 118.

86. Austen 1923a: 140.

87. Schoorl 1957: 131; Schoorl 1967: 171.