Contribution 2

Oral traditions about early trade

by Indonesians in southwest

Papua New Guinea

Introduction

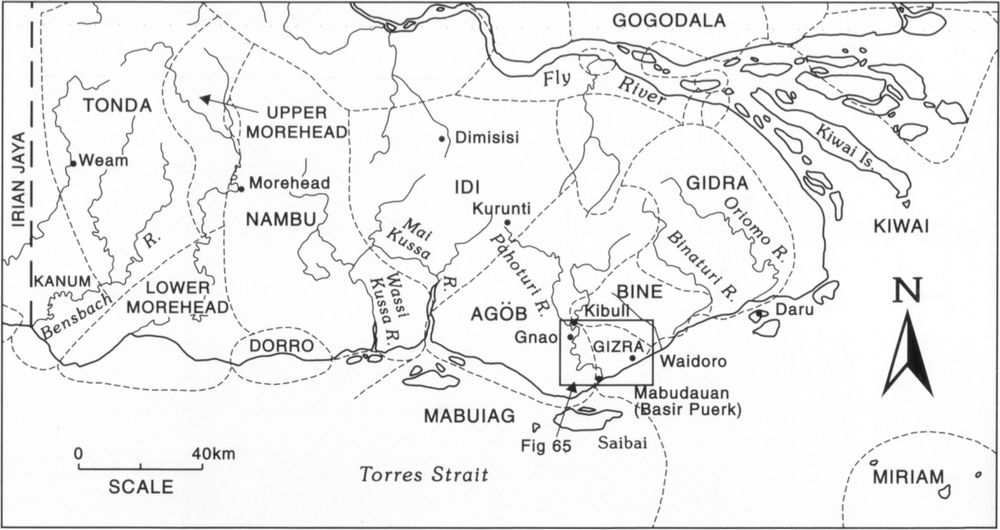

Indonesian traders have sought natural products in the coastal areas of southwest Papua New Guinea in the past. There are no written records of this early trade. However, the oral traditions of the people of this area, plus linguistic clues, indicate that Indonesian traders once visited this area. The area concerned extends along the coast from the Wassi Kussa River in the west to Kura Creek, some forty kilometres west of Daru (Figure 64).

The area is inhabited by the Gizra who live in the lower Pahoturi River area, the Agob of the Pahoturi and the lower east bank of the Mai Kussa, and the Idi on the upper parts of the Mai Kussa and Wassi Kussa River system. Although the Kiwai once had a fishing camp at Mabudauan, they did not establish a permanent village until after the British established Mabudauan as the first District headquarters in 1889.1

Foreign objects and their names

The Gizra, Agob and the Idi people seem to have had contact, prior to the arrival of Europeans, with foreigners who used metal implements and books. The names used by the speakers of these three Papua New Guinean languages for metal implements, books and other objects were probably derived from certain Indonesian words. This is the case with metal implements. For example, a knife is called turik by the Gizra, Saibai and other Western Torres Strait Islanders. The Miriam speakers of Eastern Torres Strait call it tulik, and the Bine call it turi. Turik refers to an axe rather than a knife amongst the Agob, Idi, Nambu and Tonda. Likewise the word for axe in the Kiwai dialects of Tureture, Mawatta and Mabudauan is tiriko.

Matthew Flinders, the captain of the Investigator, reports that Mer (Murray) Islanders in Eastern Torres Strait, paddled to his ship shouting tooree, toolick in 1802. This was how they asked for knives 300and axes.2 Hence these islanders and presumably others in Torres Strait knew about metal implements when Europeans such as Flinders began to visit their islands.

Other words are also used to refer to metal implements or iron. These may also have an Indonesian origin. Malil is a word for iron in Gizra, Western and Eastern Torres Strait. Kamda was another type of early metal axe. It was known in the Gizra village of Waidoro. The Tonda have a similar word, that is kamba. Both kamda and kamba may have been derived from the Malay word for axe (kampak).

Another word is beta. This was a heavy metal axe used in the past by the Gizra. The Nambu sometimes also call an axe bila. An Indonesian informant told me that belah in Malay means to ‘split’.

Salmita is a general word for axe in the Togo and Kupere dialects of Gizra. The Tonda sometimes refer to a knife as salmita. It may be related to the word scimitar, which is the name for a curved sword.

Finally, in the Togo and Kupere dialects of Gizra, the word for hoe is pambu. The same word is used by the Agob and Idi, whereas the Tonda refer to a knife as fambu.

Most of the above words are probably not indigenous; it is likely they were introduced by foreigners during the period of early trade. Another example of widespread name similarities for a foreign item is the local names for tobacco. The different names given are listed in Table 1 below and seem to be closely related.

Figure 64: Southwest Papua New Guinea.301

Table 1: Variant names for tobacco used in southwest Papua

| names for tobacco | languages |

|---|---|

| suguba | Bine, Gidra, Gizra, Kiwai and Saibai Islanders |

| sakpa | Agöb, Idi, Tonda |

| sakop | Miriam (Eastern Torres Strait) |

| sukufa | Nambu |

| sakopa | Gogodala |

It is no surprise that there are similarities between the names used on the mainland and in Torres Strait. The Gizra or Daudai-pam of the Papua New Guinea mainland formed the northern fringe of the Torres Strait trade system. There was also considerable social interaction, for example, the annual ceremony conducted by the Ait Algans of eastern Saibai. Each year they sailed to the mainland to join the Zibram of Zibar (Gizra people of Waidoro) for the ceremony called Buzural Terle. However, the focus of the early foreign trade seems to have been the mainland rather than the Torres Strait Islands, as the islanders know little about the now sacred buk (books).

Buk were once held at Basir Puerk as well as at Togo (now shifted to nearby Kulalae), Kupere, Waidoro and Dimisisi villages. We only know they existed and this knowledge has been passed down verbally through successive generations.

The incorporation of foreign introductions within the local mythology

Today many young Gizras are faced with such questions as, who brought the buk, where did they come from and what was written in them. The old people believe that the buk originated during the time that life was created at Basir Puerk (Mabudauan). According to the Gizra, Basir Puerk was the centre where three major mythical figures interacted. These were Giadap (the elder brother), Muiam (the younger brother) and Kumaz (a single woman). Kumaz is the originator of death and musical instruments, whereas Giadap is less powerful. Muiam was young, handsome, tattooed, straight-haired, light-skinned and was much more powerful than the other two. He lived on his own at a hamlet called KumKumpal at Basir Puerk. Although he was the younger brother of Giadap, Muiam was more intelligent and his activities were more complex than those of his elder brother.

Our origin myth states that the Zon Uglai (Australian Aborigines), the Siepam (Torres Strait Islanders) and the Gizra have a common birth place. This was Basir Puerk. According to the myth, the people who 302resemble Giadap are the Gizra people of Kupere and Togo, the Torres Strait Islanders and the Australian Aborigines. The Zibram of Waidoro, the Bine, Kiwai, Keremas, Motuans and other light-skinned people resemble Muiam, Giadap’s younger brother. The overall belief is that these groups and their cultures emerged at Basir Puerk. Whatever sociomagical powers and beliefs the Gizra valued and used to master their environment, the other groups were likewise equipped. In other words, these people were bound by common beliefs and customs whether on land or in the sea.

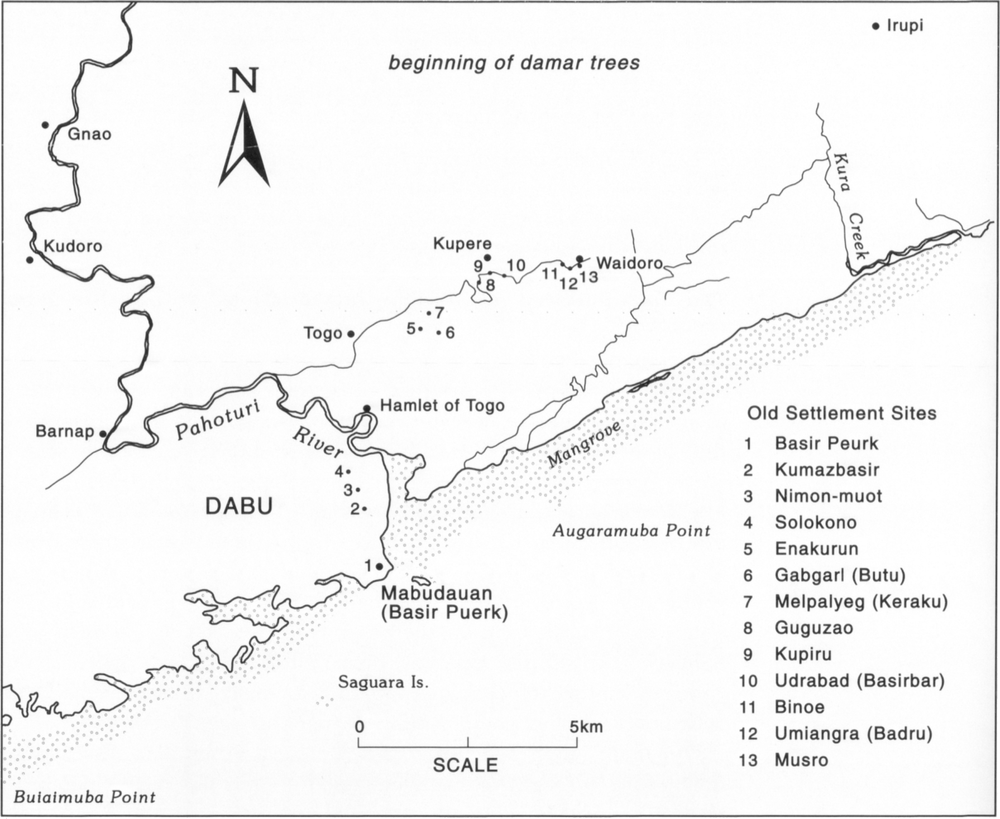

The first Gizra villages were Kumazbasir, Nimon-muot and Solokono just north of Basir Puerk at Mabudauan hill (Numandorr), see Figure 65. Later the Gizra moved across the Pahoturi River to the area of their current settlements. They still regard Basir Puerk as their birthplace and ceremonial centre.

Figure 65: Basir Puerk and hinterland.303

One of the activities which started because of the presence of Muiam at Basir Puerk was the ability to make metal implements. The Gizra believe that these were manufactured by a process which extracted iron from the granite rock at Basir Puerk.3 It is also believed that when iron was being manufactured there, men of different races lived side by side.

Although Muiam dwelt in a hamlet called Kumkumpa4 at Basir Puerk, he also travelled extensively along the coasts of southwest Papua New Guinea. I think this culture hero was a real person who once travelled as far east as the Gulf Delta. It must have happened long ago, as the accounts of his travels and activities have been passed on for many generations. They have won a prime place within the myths and legends of this coast. He was engaged in many different activities. Most of these were quite new to the local people and for this reason they believed his acts were supernatural.

He has various names in the myths of the coastal tribes. We call him Muiam. The Kiwai call him Sido.5 The Gapo of Wabo call him Hido, whereas the Purari Delta people and Elema call him Iko.6

In most versions of the myth, at least one episode tells that the hero was the first man to have a sexual relationship with a female. He is then killed and as a consequence death becomes a reality. In many versions he is the originator of many things, including life and death. The hero comes from the west to the east and when he dies his soul goes back to the west and prepares a place for all mankind. Douglas Newton7 stresses that Hido’s path was subsequently taken by many migrants from Kiwai Island. Many elements of culture are shared as a result of this hero’s activities and travels, for example, the widespread ‘long-house cult’.

The Gizra believe that many activities, including the manufacturing of metal implements, came to an end due to European contact. The granite deposit then lay idle. Although the library at Basir Puerk was not used any more, two different men from each of the Gizra villages came everyday to guard it. The annual Dabu Terle (initiation ceremony) also continued. This ceremony used to last for six months and within this time the initiates roamed the area between Dabu and Basir Puerk, conducting all sorts of rituals and learning the secrets of their society.

Sites associated with these foreign introductions

Previously all Gizra villages consisted of three hamlets and each had a kobo (men’s house). Out of the nine hamlets, there were only three leading ones. That is to say, each of these leading kobo had a buk. The kobo at Zibar (Waidoro) was regarded as being much more powerful than the other two, as it also had a curved piece of malil (iron) which 304was placed underneath the buk. This symbolised the supernatural hero Muiam. Many mythical figures are portrayed by carved representations, but Muiam was never symbolised by any other form.

It is also claimed that there is a buk at Dimisisi in the Idi area. The local people say the buk is not a modern one, but was there for many years before European contact. It has been passed down by many generations and is believed to be associated with a very old boat. This is also very sacred and is located at the headwaters of the Mai Kussa River. The boat is in the water, but is tied to a tree at the bank of the river by a chain. The clan that is in charge of the buk also owns the sacred site where the boat is located. Access to this area is restricted to members of this clan. No other person can enter the area unless they have undergone certain rituals organised by the clan’s elders.

In the Agöb area there is another sacred site near the headwaters of the Pahoturi River. Once again this area can only be entered by elderly male members and initiates (kernge) from the local clan. The boats are believed to possess supernatural powers originating from dead relatives (mari). In other words, one has to be transformed into the image of a dead spirit in order to see the boats or even to enter the area.

The local people and other nearby tribesmen believe that the boats are the ‘Arks’ belonging to Noah, that drifted there after the flood. The only reason why the people believe they are ‘Arks’ is merely because of the biblical stories they have heard. In reality they may be old boats used by early traders to this area. The explanation could be that the boats were not in good enough condition for the traders to use on their return journey, or perhaps they were left behind when the local people became hostile and forced the traders to leave hastily. They may have abandoned some of their boats and fled for their lives.

How the introductions may have come about and what happened when the traders came no more

It is possible the boats were owned by Indonesian traders from the Seram or Aru Islands who were in search of damar, a tree gum, as suggested by Pamela Swadling in Chapter 9. In the past damar was used like a candle. The name for this gum-producing tree in Agob and Idi is yoto. The Agöb, Idi and Gidra people used to collect damar and burn the gum to produce light at night. However, in the Nambu area of the Morehead District, the wood rather than the gum of the tree was favoured. The trees grow naturally and plentifully throughout the Oriomo Plateau.

The books may have been the diaries which the early traders distributed to the local headmen. These were then available for use during their visits to these areas. Basir Puerk is the traditional centre 305from whence cultural influences came forth in this region. At one time it may have been a trading post from which these foreigners operated into the hinterland. The people also believe that it was from this centre (Basir Puerk) that ideas and powers were transmitted to the kobo (men’s houses).

These foreign items and influences were no longer reaching my area at the time of European contact. The metal implements have now rusted away. The original practical uses of the buk are forgotten, but their status within our society remains. I assume that metal implements were not the only trade items. There may have been others such as mirrors (barida) and glass beads (kusal). Some traces of these may be found by a thorough archaeological investigation of some of the early settlement locations of the Waidoro, Togo and Kupere. These would include the following sites: Barnap, Binoe, Gabgarl, Enakrun, Guguzao, Melpalyeg, Kupiru, Musro, Udrabad and Umiangra, which were last inhabited three generations ago.

Some buk may have been taken when Torres Strait Islanders made a retaliatory raid in about the 1890s. Others were probably lost during the frequent moves which had to be made to avoid the Tugeri raiders. This meant the buk would have been kept in poor storage facilities and were possibly exposed to the rain. The buk were last seen three generations ago and I assume that my people had them at least another three generations back from that time; otherwise the mythical associations about these objects would presumably not have arisen.

I am not in a position, since I have not been initiated, to understand the full sacred importance of the buk. There is an underlying belief that the buk were associated with the source of life. I and other young Gizra believe this not to be the case. We think that the myths and supposed powers of the buk and metal implements exist because they were first introduced long, long ago. Then they ceased to come. Some time afterwards Europeans came along.

Our old people claim we also had a school before Europeans came

Once there was a school in Zibar (Waidoro). In this school, students were taught the rituals and the secrets of the fertility of coconuts. It ceased operation due to the pregnancy of a young girl. A widespread belief among elderly Gizra men is that the names such as urlpagi-siikull (school),8 buk (book), barida (mirror) and malil (iron) are not foreign but their own, because they had them before European contact.

Recent Indonesian traders from West Papua (former Dutch New Guinea)

Early last century, and in particular after the Second World War, some light-skinned foreigners entered my area. They rode on horseback 306and came from Dutch New Guinea. These foreigners were known to the Gizra and Agöb as ‘Malayo’. Some Gizra people were given money in return for food, while others were given penknives. Later they were advised in Daru that the money was valueless in Papua and government officials inquired as to how Gizra people had obtained this foreign currency. The foreigners also taught the Gizra and the Kiwai people of Mabudauan how to play soccer and hockey. The local people can still recall some of the songs sung by the outsiders.

Here are two examples:

- Inu intu waraike

Sapelang jala a sapelang meri

Dangan mari saian baia … o

O … Arumbai e … Malayo

- Alang alang dipania pania adi dipania tu

Kista Malayo

Oli oli wanja wanja

Wanja mela tu kosta Malayo

Some foreigners gave horses to their trade partners in the Weam area of the Morehead District. This was also the case in Ngao village in the Agöb area. Although the local people were taught how to ride horses and at times used them for carrying heavy loads, they remained frightened of them, probably because they had no previous experience with such big animals. The horses were also a nuisance because they fed on the leaves of garden crops and some developed horrible skin diseases. For these reasons the village people killed the horses in the Agöb area. However, some horses escaped and have been breeding wild. These wild horses can still be found in the Weam area of the Morehead District.

An informant from the Morehead area stated that his people referred to the foreigners as ‘Dutchy from the Balanda Government’. The people believed the Dutch were moving their territorial boundary eastwards with the aim of bringing part of the Western Province under Dutch control. Many village people were given penknives as presents. The names of many trade partners are still easily recalled, as well as the strange experiences they had with the horses and saddles.307

Notes

1. A Gidra-speaking man called Bidebu played a significant role in the history of the Kiwai settlements of Tureture, Mawatta and Mabudauan. Bidebu controlled the area between the Oriomo and Binaturi (Badengle Tage) Rivers. His associations included links with the Bine-speaking people of Kunini, Tati, Glulu and Badu (Irupi), as well as with the Gizra village of Zibar (Jibaro-Waidoro).

It was Kiwai people from Kadawa village on the south bank of the Fly River mouth who came to develop associations with the people of the Trans Fly coast. These Kiwai were led by Gamea. Bidebu after meeting Gamea assisted Gamea and his people. This is evident from the clan histories of the current Tureture, Mawatta and Mabudauan populations. Their lines have a Kiwai origin through Gamea, Gidra through Bidebu, as well as Gizra, Agöb and Torres Straits origins.

The first Gizra to be associated with the Kiwai at Mawatta were the Waidoro. They met when the Kiwai went on fishing trips to Kura, Iarika-Zanarangbad, Dogai and Iamaz. Landtman (1917: 406–7) reports that Mainau arranged an ambush against the Gizra (Djibaru) in order to obtain heads for the marriage payment to the relatives of his son’s Kiwai wife at Mawatta. Gamea’s father Mainau was killed when the Gizra of Waidoro avenged this attack. The Gizra not only attacked Mawatta, but also the Bine at Masingara and the Torres Strait Islanders on Saibai and Yam Islands. It was sometime after this fight that the Kiwai came to Mabudauan. The Torres Strait Islanders also made a retaliatory raid and seized some of our sacred relics.

2. Haddon 1935 (1): 7–10.

3. The literal translation of Basir Puerk in Gizra is village swamp. This seems a misnomer as the area is slightly higher than the surrounding country and thus cannot be considered swampy. The Malay words Pasir putih not only have similar sounds to Basir Puerk, but also have a relevant meaning. Pasir means sand and putih is white. When looking at the coast from out to sea, the hillock of Mabudauan, with its stone outcrops, gleams like white sand. This makes it a very distinctive feature on the Trans Fly coast. Perhaps Pasir Putih was the original name for this place and over time the Gizra changed the name to words they knew, namely Basir Puerk.

4. Kumkumpal does not sound like a Gizra word. The literal translation of this name is the area where a lot of a particular type of ginger is found. Again this seems a misnomer as ginger is not found there. Perhaps the name is a corruption of the Malay word kampong, meaning village.

5. Landtman 1927.

6. Newton 1961.

7. Newton 1961.

8. The Malay word for school is sekolah.