8

The collapse of polling as a way of asking about policy preferences: campaign polls in Australia and Britain

Campaign polls in Australia and Britain

The development of opinion polls, George Gallup argued in defence of polling, opened the way to a new ‘stage of democracy’: the continuous assessment of ‘public opinion on all the major issues of the day’ (Gallup and Rae 1940, 125). During campaigns, polls were never about issues alone, of course, ‘major’ or otherwise; they were also about how respondents would vote, what they thought of the party leaders, and a number of other things. But the position of respondents on some of the political issues of the day was a substantial part of the mix. This was true from the earliest years of polling in the United States, in Britain (see Goot 2017, 108, for the 1945 election) and especially in Australia (see APOP 1943a, 1943b, for the 1943 election).

How large a presence do questions about issues have in the pre-election polls now? To answer this question, this chapter asks three others. What sorts of things did the opinion polls ask about during the 2016 Australian election campaign and the 2015 British election campaign? How did the agendas of the Australian polls differ from the agendas of the British polls? And how different were the preoccupations of the various polling organisations in Australia and how did they vary in Britain?

While the focus is on the polls published during the Australian campaign, this chapter documents considerable variation not only in what polling companies in Australia concentrated on but also in the preoccupations of polling companies in Britain. If some concentrated on issues of public policy, most did not; a greater number gave little, if any, attention to issues of this kind. Moreover, when issues of public policy were raised, the questions weren’t necessarily designed to ascertain where respondents stood, Gallup’s hope; for the most part they were intended to establish which party or which party leader respondents most trusted or thought best able to handle the issue, something by which Gallup set much less store. The newspapers that commissioned relatively few questions about issues included elite papers − the Australian; and in Britain, the Guardian and Observer – not just the tabloids. What the pollsters polled was a function of who (if anyone) commissioned the polls, the markets those commissioning the polls operated in (including their assessment of what their audiences wanted), and the technology deployed.

During the Australian campaign, all but one of the seven polling firms reported how respondents intended to vote. All but one reported respondents’ views of the party leaders. All but one asked questions about the election’s outcomes. And all but one posed questions about what they considered to be election issues. In every case, a different organisation was the odd one out. Only two pollsters sought respondents’ views of the parties. Only one asked respondents what they thought about individual candidates. The total number of questions asked by any of the polls ranged from 14 to 247. The kinds of questions the polls asked varied considerably as well.

The attention given to issues, overall, was relatively small – less than that given to the leaders and only half as great as that devoted to ascertaining how respondents might vote. If the Australian election, as one economics commentator argues, was ‘fought on genuine policy differences on business tax cuts, education spending, super tax changes, multinational tax avoidance and Labor’s negative gearing tax changes’ (Irvine 2017), there was little sign of it in the polls. While border security may have been an issue that strengthened the Liberals and economic insecurity an issue that drew voters to Labor, the polls showed very little interest in these issues either. The only issue in which most of the polls showed an interest was Medicare – an issue of security, to be sure, but not one that occupies a central place on most analysts’ ‘security’ agendas. The polls showed an interest in Medicare relatively late in the piece, not because they thought respondents’ views in themselves worthy of consideration, but because they sensed the issue might be decisive (‘Mediscare’).

A comparison of the Australian and British polls shows some striking similarities; among them, the near-collapse of questions about respondents’ position on issues – the polling, Gallup argued, which justified the place of polls in a democracy because it conveyed to the parties what voters actually wanted, regardless of which party they voted for or which party formed government (Gallup and Rae 1940, v, 12–14). But a comparison also demonstrates important differences between the Australian and British polls, including differences in: the intensity of polling; the greater emphasis in Australia on establishing how respondents were likely to vote; and the greater emphasis in Britain on reporting party images, engagement with the campaign and expectations about the election’s outcomes.

The polling organisations and the organisations for which they polled

In Australia, polling organisations were either commissioned by the media or paid their own way. Newspoll was commissioned by News Corp’s flagship Australian newspaper. Ipsos, commissioned by Fairfax (and promoted by Fairfax as Fairfax Ipsos), published polls in the Sydney Morning Herald, the (Melbourne) Age and the Australian Financial Review. Omnipoll was commissioned by Sky News, part-owned by News Corp’s 21st Century Fox. Galaxy was commissioned by News Corp’s mainland metropolitan mastheads – the Daily Telegraph (Sydney), Herald Sun (Melbourne), Courier-Mail (Brisbane) and Advertiser (Adelaide). ReachTEL was commissioned variously by Channel 7, Fairfax, the Hobart Mercury and the Sunday Tasmanian – the last two owned by News Corp as well. Essential Research, close to the the union movement and the Labor Party, was self-funded though published by the political website Crikey, as was the Roy Morgan Research Centre, which polled on a continuing basis in the hope of being able to sell its findings; but it also posted some of its results online, perhaps as teasers.

The time when all the campaign polling, other than the exit polls, was commissioned by the print media had long passed. Of the questions and answers published during the 2016 campaign less than half (46.2 per cent) were sponsored by a newspaper or newspaper group. A substantial proportion (16 per cent) was paid for by a television station or TV network. But more than a third (37.8 per cent) were provided by companies that paid for their own fieldwork. During the British campaign, the proportion of the questions asked on behalf of the press and TV (ITV News) was much higher (79.7 per cent), the proportion asked independently of the media (20.3 per cent) much lower (derived from Cowley and Kavanagh 2016, 235; Goot 2017, Table 7.2).

If some of the firms were new to election polling, most were not. Of the new entrants, Ipsos used standard telephone interviewing techniques (CATI or Computer Assisted Telephone Interviews), as had its predecessor at Fairfax (Nielsen) – though Ipsos extended Nielsen’s telephone reach to include mobiles – while Omnipoll polled online. Among those that had polled in 2013, some used the same techniques they had used then: Morgan deployed a mixture of face-to-face interviewing and SMS; ReachTEL, using landlines, continued to robopoll − a technique formally known as IVR or Interactive Voice Recognition. Others had changed their methods since 2013: Galaxy and Newspoll – previously conducted via CATI – used a combination of online and robopolls restricted to landlines.

Most of the polling was done by robopoll or conducted online. CATI polls, not long ago the industry standard, had become too expensive; with revenue from media advertising and newspaper sales in sharp decline, cost-cutting was imperative. The use of CATI had not entirely disappeared; Ipsos used it. But even a newspaper company inclined to CATI had to draw the line somewhere; when Fairfax commissioned polls in single seats, it couldn’t afford CATI so it didn’t commission Ipsos. Done well, a poll in a single seat needed a sample similar in size to a poll done nationwide. Ipsos, however, wouldn’t cut corners by changing modes; nor, in 2013, had Nielsen. For Fairfax, considerations of quality in its single-seat polls were to be trumped, as they were in 2013 (Goot 2015, 124), by considerations of cost – backed, no doubt, by a quiet confidence that its reputation would be judged not by how accurate its single-seat polling turned out to be, but by the accuracy of its nationwide results.

‘Despite elections being awash with polls’, one advertising executive remarked after the 2013 election, ‘most are national polls’ (Madigan 2014, 40). In fact, most of the polls in 2016 were not conducted nationally (see Table 8.1); nor were they in 2013 (Goot 2015, 133). The main reason: a widespread belief, however mistaken (Goot, in press), that elections are won in the ‘marginal’ seats not won on the size of the national swing. Although every polling organisation produced national polls – three (Essential, Ipsos and Omnipoll) produced nothing other than national polls – barely a quarter of the 2016 polls were conducted nationally. Pollsters’ mostly produced single-seat polls; 25 of the 33 polls produced by Galaxy, 25 of the 29 produced by Morgan, and 24 of the 31 from ReachTEL were single-seat polls. Two polls were state polls. One other poll was an exit poll conducted by Galaxy outside 25 polling booths.

Table 8.1: Number of polls conducted and published in Australia between the dissolution of the Parliament (9 May) and the day of the election (2 July 2016), column % in brackets.

| Essential | Galaxy | Ipsos | Morgan | Newspoll | Omnipoll | ReachTEL | Row N (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mode | Online | Online + robo | CATI | Multimode | Online + robo | Online | Robo | |

| Sponsor [outlet] | [Crikey] | News | Fairfax | [website] | The Australian | Sky News | Fairfax/News | |

| Dates | 12 May – 30 June | 10 May – 2 July | 17 May – 29 June | 14 May – 19 June | 19 May – 28 June | 19 May – 2 July | 12 May – 30 June | 10 May – 2 July |

| National | 8 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 7 | 32 (25.4) |

| State | 1 | 1‡ | 2 (1.6) | |||||

| Single seats | 29* | 25 | 13* | 24* | 91 (72.2) | |||

| Other | 1# | 1# (0.8) | ||||||

| Column N | 8 | 33 | 4 | 29 | 18 | 3 | 31 | 126 |

Notes: Excludes ReachTEL polls conducted for and released by the NSW Teachers Federation, the Lonergan Research polling conducted for and released by the Greens, and the Community Engagement poll conducted for and released by Make Poverty History and Micah Australia.

* Robopoll

‡ Aggregation of single-seat polls in South Australia

# Exit poll conducted at 25 booths

What the polls polled

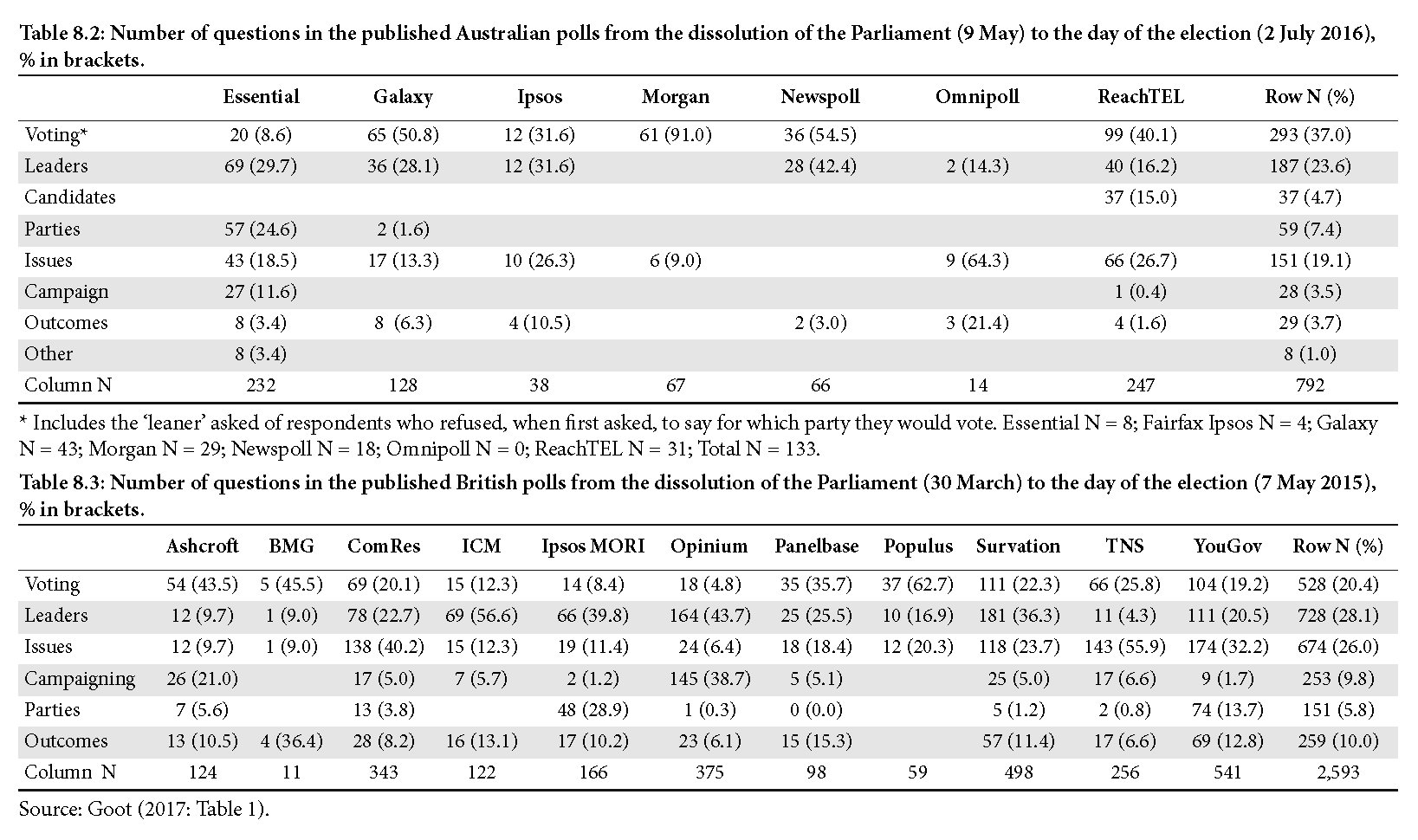

In the 55 days between the dissolution of the Parliament on 9 May and the holding of the election on 2 July, the polls that were published asked 792 substantive questions. Across 126 separate polls (Table 8.1), this meant an average of just over six (6.3) questions per poll (derived from Table 8.2). Essential, which conducted eight polls and asked 232 questions, averaged 29 questions per poll; its profile was quite different from that of any other polling firm. At the other extreme, Morgan conducted many more polls (29) but averaged only two or so (2.3) questions per poll. For the other pollsters, the corresponding figures in descending order of question intensity (the number of questions asked divided by the number of surveys) were: Ipsos, 9.5 (38 questions, four surveys); ReachTEL, 8 (247 questions, 31 surveys); Omnipoll, 4.7 (14 questions, three surveys); and Galaxy, 3.9 (128 questions, 33 surveys).

In Britain, a shorter 34-day election campaign saw 12 polling organisations produce 138 polls, using online methods or CATI but no robopolls (Sturgis et al. 2016, 22). Most were conducted across Britain; only 34 were in groups of seats, in Scotland, or across other populations. The polls generated 2,593 questions, an average of roughly 19 (18.8) questions per poll (see Table 8.3). The question intensity for four of the 12 pollsters was about as high as or higher than the highest of the Australians; for only two was it lower. In Australia, the poll with the highest intensity was self-funded; in Britain, it was not. But one of the self-funded polls in Britain, TNS, polled as intensively as the highest intensity poll in Australia, also self-funded. Even when they were not being paid, the publicity benefits meant a number of pollsters were keen to participate.

Access the digital text version of Table 8.2 and Table 8.3.

Voting intentions

The questions pollsters most frequently asked during the Australian campaign were those that sought to establish how respondents were going to vote; 37 per cent of all the questions were of this kind. Nonetheless, such questions were not the most commonly asked by every pollster. Questions about the vote accounted for nearly all (91 per cent) of Morgan’s questions, over half (54.5 per cent) of Newspoll’s and half (50.8 per cent) of Galaxy’s; but for Essential, such questions figured much less prominently (8.1 per cent of its questions) (Table 8.2). Typically, pollsters asked two questions in their attempt to elicit respondents’ voting intentions: one, about how they intended to vote; the other, for those who refused to answer or were ‘undecided’, about the party to which they were ‘leaning’.

The most frequently reported figure, however, was the two-party preferred, a figure most pollsters didn’t arrive at directly but calculated from the distribution of the minor party and independent votes in 2013; Essential (in its last two polls), Ipsos and ReachTEL (except for its initial polling in Tasmania) were the only pollsters that attempted to establish the respondents’ two-party preferred vote directly. Essential also asked respondents whether they intended ‘to vote at a polling booth on election day’ or whether they would be casting their ‘vote before election day’ (for a fuller account, see Goot, in press).

As well as asking how they were going to vote in the House of Representatives, ReachTEL in each of the Tasmanian seats asked respondents a week before the election whether they were ‘more or less likely to vote for [Jacquie[sic] Lambie/Richard Colbeck/Lisa Singh] in the Senate this time than at the 2013 election’, these candidates having either disowned the party that had endorsed them in 2013 (Senator Lambie now heading the Jacqui Lambie Network) or been demoted by their party on its Senate ticket (Senator Colbeck by the Liberals; Senator Singh by Labor). These were the only questions any of the pollsters asked about voting for the Senate.

In Britain, questions about how respondents intended to vote were not the questions most frequently asked; questions about leaders (28.1 per cent of the questions asked) and issues (26 per cent) loomed larger. Questions about how respondents were likely to vote taken together with a number of questions not asked in Australia – about whether respondents were likely to vote, how likely they were to change their mind, their party identification, why they intended to vote for a particular party or candidate, whether they were voting tactically, how they had voted last time, and so on – accounted for a much larger proportion of all the questions asked in Britain (20.4 per cent). Comparing questions about respondents’ intended (first preference) vote, the proportion of questions about voting intentions in the Australian polls was 31.6 per cent while the proportion in the British polls was not even 10 per cent, a figure lower than it might otherwise have been because of the failure, apparently, of most British polls to inquire of ‘undecided’ respondents about the party to which they were ‘leaning’ (Goot 2017, 91).

Leaders and candidates

In the Australian campaign, questions about the party leaders, overwhelmingly about the leaders of the Liberal and Labor parties, accounted for a quarter (23.6 per cent) of all the questions asked, slightly less than half the number of questions asked about how respondents would vote. But the focus on the prime minister, Malcolm Turnbull, and the leader of the Opposition, Bill Shorten, varied markedly. Newspoll and Ipsos focused almost as closely (Newspoll) or as closely (Ipsos) on the two leaders as they did on the vote. Essential was even more focused on the leaders than it was on the vote; it asked more than three times as many questions about the leaders as it did about the vote. Indeed, it asked more questions about the leaders than did any other poll. It included questions on the leaders’ various attributes and on which of the leaders respondents would ‘trust most to handle’ a range of issues: ‘regulating the banking and finance sector’; ‘supporting Australia’s manufacturing industries’; ‘ensuring big companies pay their fair share of tax’; ‘protecting the Great Barrier Reef’; ‘funding hospitals’; ‘addressing climate change’; ‘making housing more affordable for first home buyers’; ‘looking after the needs of pensioners’; ‘funding public schools’; ‘maintaining workers’ wages and conditions’. Omnipoll, which published none of the answers to its voting intention questions, asked just two questions about the leaders. Galaxy asked many fewer questions about the leaders than it did about the vote. ReachTEL devoted less than half of the questions to leaders that it devoted to how respondents would vote. Morgan, which focused more intensely on the vote than any other pollster, ignored the leaders altogether; although in 1968 his father had introduced the regular reporting of leadership approval, Gary Morgan, his successor, didn’t believe such questions now to be of much if any value (pers. comm).

Three of the pollsters raised questions about internal party rivals to the leaders. The most provocative was Galaxy’s. In a national poll taken late in the campaign, Galaxy wanted to know ‘If Tony Abbott was the leader of the Liberal Party’ for which party would respondents vote? ReachTEL, at the beginning of the campaign, had wanted to hear from its Tasmanian respondents whether they were ‘more or less likely to vote for the Coalition since Malcolm Turnbull replaced Tony Abbott as prime minister’? Omnipoll went down a quite different track: who would respondents prefer as leader of the Liberal Party (Turnbull, Scott Morrison, Julie Bishop or Tony Abbott); who would they prefer as leader of the Labor Party (Shorten, Anthony Albanese, Tanya Plibersek or Chris Bowen)?

There was also some interest in what respondents knew – not about the leaders but about other frontbenchers. Essential asked respondents to say, ‘without looking it up’, whether ‘the current Treasurer’ was Morrison, Joe Hockey or Chris Bowen. Only ReachTEL asked about MPs not on the front bench: ‘How many of the 12 Tasmanian senators do you think you can name?’ Whether they really could, ReachTEL didn’t ask. It also asked what respondents thought of the candidates contesting seats in the House of Representatives.

In Britain, less than half of the questions about leaders were about Prime Minister David Cameron or the Leader of the Opposition Ed Miliband. Moreover, while a third (33.2 per cent) of the questions about the Australian leaders were about which of the two leaders would make the better prime minister, in Britain just 5 per cent of the questions on the leaders were of this kind. With regionally based parties of growing importance, a range of governing coalitions possible, and several party leaders participating in a televised ‘leaders debate’ – not only Cameron and Miliband but also Nick Clegg (Liberal Democrats), Nigel Farage (UKIP), Natalie Bennett (Green Party of England and Wales), Nicola Sturgeon (Scottish National Party) and Leanne Wood (Plaid Cymru) – party leaders from a number of parties attracted the attention, however fleeting, of more than one poll; so, too, did Alex Salmond (former leader of the SNP), though he was only an SNP candidate (Goot 2017, 95–96). While the proportion of questions devoted to party leaders in Australia (23.6 per cent) may not have been very different from the proportion devoted to party leaders in Britain (28.1 per cent), the range of leaders in the Australian polls, if not the range of questions about the leaders, was much narrower.

The parties

Across most of the polls conducted during the Australian campaign, questions about the parties – the groups they represented, the values they embodied, the ways in which they operated – figured in few of the polls. While six of the seven polls asked questions about the leaders, only two asked questions about their parties − questions other than those about which party could be ‘trusted’ or was ‘best’ on particular issues (see below) – and the poll that asked almost all these questions (Essential) did so off its own bat. Australia might have a coalition government; it might have other parties represented in the Parliament; but the polls were interested, almost exclusively, in the Liberal and Labor parties.

Essential focused on whether Liberal or Labor was best for particular groups. A battery of questions sought to report which of the two was seen as better in relation to: ‘representing the interests of large corporate and financial interests’; ‘handling the economy in a way that helps small business’; ‘handling the economy in a way that helps the middle class’; ‘handling the economy in a way that helps you and people like you the most’; ‘handling the economy in a way that tries to take the interests of working families into consideration as much as it takes the interests of the large corporate and financial groups’; ‘representing the interests of you and people like you’; ‘standing up for the middle class in Australia’; ‘being more concerned about the interests of working families in Australia than the rich and large business and financial interests’; ‘representing the interests of Australian working families’. The phrase ‘working families’ had featured in the Your Rights at Work campaign mounted by the unions against the Howard government’s WorkChoices legislation, a campaign in which Essential Media Communications played a central part (see Muir 2008).

Separately, Essential asked whether ‘the following groups of people would be better off under a Liberal government or a Labor government’ or whether it would make no difference: ‘large corporations’; ‘people and families on high incomes’; ‘banks and other financial institutions’; ‘families with children at private school’; ‘small businesses’; ‘farmers and other agricultural producers’; ‘people and families on middle incomes’; ‘average working people’; ‘recent immigrants to Australia’; ‘pensioners’; ‘people with disabilities’; ‘unemployed people’; ‘single parents’; ‘families with children at public school’; ‘people and families on low incomes’. At the start of the campaign Essential had also asked: ‘whose interests . . . the [Labor/Liberal] Party mainly represent: working class; middle class; upper class; all of them; none of them’? In Adelaide and Port Adelaide, Galaxy would ask: ‘Who do you think would best represent the interests of South Australia in Canberra: Labor Party; Liberal Party; Nick Xenophon Team’?

Another way of exploring party images was to focus on other things that might count towards a party’s success. Presenting its respondents with ‘a list of things both favourable and unfavourable that have been said about various political parties’, Essential asked which of the following fitted the Labor Party and which fitted the Liberal Party: ‘will promise to do anything to win votes’; ‘looks after the interests of working people’; ‘moderate’; ‘divided’; ‘understands the problems facing Australia’; ‘have a vision for the future’; ‘out of touch with ordinary people’; ‘have good policies’; ‘trust to manage a fair superannuation system’; ‘clear about what they stand for’; ‘has a good team of leaders’; ‘too close to the big corporate and financial interests’; ‘trustworthy’; ‘keeps its promises’; ‘extreme’.

In Australia, more than in Britain, questions about the parties sought to explore the perceived links between parties and groups. The emphasis on groups rather than issues suggests a quite different understanding of the wellsprings of electoral behaviour (see Achen and Bartels 2016). The fact that this was mostly done by Essential, a polling organisation with links to the unions, surely is not coincidental.

Issues

The attention the Australian polls gave to issues, while not high, was considerably greater than they gave to anything other than the leaders or the vote; 19.1 per cent of all the questions the polls asked were about issues. ReachTEL devoted a quarter of its questions to issues; Essential and Galaxy, rather less. Off much smaller bases, Omnipoll devoted nearly two thirds of its questions to issues, Ipsos about a quarter, and Morgan much less. Only Newspoll steered clear entirely (Table 8.2). Insofar as ‘threats’ figured in the polls’ agendas, it was here that one was most likely to find them.

Valence issues

Most of the questions about the parties during the Australian campaign were about ‘valence’ issues − issues that ‘involve the linking of the parties with some condition that is positively or negatively valued by the electorate’ (Stokes 1966/1963, 170). Morgan twice asked a question made famous in Richard Nixon’s campaign for the White House: did respondents think the country was ‘heading in the right direction’ or ‘heading in the wrong direction’? It was the only valence issue Morgan raised and the only valence issue raised by any of the pollsters that did not require the respondent to consider, directly, the merits of one or more of the parties (or, as we have noted in relation to the Essential poll, the party leaders).

Essential asked, in two of its polls, whether respondents trusted Liberal or Labor more on ‘security and the war on terrorism’; ‘management of the economy’; ‘controlling interest rates’; ‘managing population growth’; ‘treatment of asylum seekers’; ‘ensuring a quality water supply’; ‘ensuring a fair tax system’; ‘housing affordability’; ‘ensuring a quality education for children’; ‘ensuring the quality of Australia’s health system’; ‘addressing climate change’; ‘protecting the environment’; ‘a fair industrial relations system’; and ‘protecting Australian jobs and local industries.’ Essential also asked ‘which party would you trust more to secure local jobs in your area and nationally?’ ReachTEL, in three of its national polls, asked ‘which of the two parties [sic] [the Coalition or Labor]’ respondents ‘trusted most to manage’: ‘the economy’; ‘health services’; ‘education’; ‘the issue of border security’. In two of its Tasmanian polls it also asked ‘which of the following parties [Liberal, Labor, the Greens, Other/Independent] do you trust most to manage the economy and the core issues facing Tasmania’? The possibility that respondents might trust one party on some issues but some other party on others was a possibility for which the question did not allow.

A variant of the ‘most trusted’ question was a question about the ‘best party’. Ipsos asked ‘which of the major parties, the Labor Party or the Liberal–National Coalition . . . would be best for handling’: ‘health and hospitals’; ‘education’; ‘the economy’; ‘the environment’; ‘interest rates’; ‘asylum seekers’. Essential asked which party, Labor or Liberal, would be best when it came to ‘handling the economy overall’. And having asked respondents in Tasmania which of a number of issues would most influence their vote (see below), ReachTEL went on to ask: ‘Thinking of the issue you just chose, which of the following two parties [Liberal, Labor] has outlined the best plan for this area?’

Vote drivers

Other questions were designed not to see which party was preferred on an issue but to establish whether certain issues would influence, or had influenced (some respondents having voted already), respondents’ votes. These questions assumed that it was issues rather than anything else that drove the vote and that the respondents, most of them not especially interested in politics, would be able to identify which issues these were.

Early in the campaign, Galaxy asked respondents in six New South Wales seats whether ‘the federal Budget handed down by Scott Morrison last week’ would make them ‘more likely to vote Liberal at the forthcoming federal election, less likely to vote Liberal or . . . not influence the way that you vote at the federal election?’ Later Galaxy also enquired, in four South Australian seats, about the impact of ‘the decision to build the next generation of navy submarines in South Australia’ on respondents’ likelihood of voting for the Liberals; and, in four Victorian seats, about the impact of ‘[Victorian premier] Daniel Andrews and the [Victorian] state government’s handling of the CFA [Country Fire Authority] pay dispute’ on the likelihood of respondents’ voting Labor.

From the beginning of the campaign to the end, ReachTEL asked more questions about vote drivers than were asked by any other poll. In Tasmania for the Sunday Tasmanian, ReachTEL asked which of the following would ‘influence’ each respondent’s ‘decision most’: ‘education funding’; ‘health funding’; ‘job creation packages’; ‘management of the economy’; ‘the environment’; ‘same sex marriage’; ‘stopping the boats’. Later, for the Mercury, it repeated the question. In six of its seven national polls for 7News it varied this list and altered its language: ‘education’; ‘creating jobs’; ‘health services’; ‘management of the economy’; ‘border protection and asylum seekers’; ‘roads and infrastructure’; ‘climate change and the environment’. It used the same list in the seats it polled for 7News. In the seats it polled for Fairfax, it varied the list again: ‘economic management’; ‘hospitals’; ‘schools’; ‘national security’; ‘industrial relations’; ‘climate change’. ReachTEL (like Galaxy) also asked respondents about the importance of particular issues in deciding how they would vote: nationally, superannuation and the NBN; in single seats, whether ‘Britain voting to leave the European Union, or Brexit as it is referred to in the media, impacted your vote at all’ and, if so, whether it had made it more likely respondents would vote for Labor, the Coalition, a minor party or an independent.

Omnipoll, in the field on the day of the election and the day before, also presented respondents with a list of issues and asked, in relation to each, whether it was ‘very important, fairly important or not important to you on how you voted/will vote’. In descending order of support, as rated by the respondents, the issues were: ‘health and Medicare’; ‘education policy and spending’; ‘Budget balance and economic management’; ‘superannuation changes’; ‘proposed negative gearing changes’; ‘moves to control building unions’; ‘company taxes’. Galaxy, in its exit poll, asked respondents to name, from a list, the issues that had ‘influenced’ their vote. (As with Omnipoll, some issues were really two issues, not one.) The Galaxy issues, again in descending order of support, were: ‘health and Medicare’; ‘education/TAFE’; ‘the cost of living’; ‘the economy/balancing the budget’; ‘job creation’; ‘leadership/Malcolm Turnbull/Bill Shorten’; ‘climate change’; ‘same sex marriage’; ‘housing affordability/negative gearing’; and ‘asylum seekers’.

‘Health and Medicare’ and ‘education policy and spending’ (Omnipoll)/‘education’ (Galaxy) topped both lists; but they were the only issues that appeared on both lists. In the Omnipoll these issues were named much more often by Labor than by Coalition respondents, the gap between the two sets of respondents exceeding 20 percentage points. ‘Budget balance and economic management’ and ‘moves to control building unions’ were named more often by Coalition than by Labor respondents – and by similar margins. Of the 11 issues in the Galaxy list, ‘the cost of living’ and ‘climate change’ were also named more often by Labor respondents (a gap of 10 percentage points or more) than by those who had voted for the Coalition, while ‘the economy’ and ‘Turnbull/Shorten’s leadership’ were named more often by Coalition respondents than by those who had voted for Labor. Threats and insecurities were structured by party. However, the proportion that nominated any of these issues as important was vastly greater than the proportion whose vote was likely to have been affected by them. Did respondents name issues that they really thought had influenced their vote; or, having voted for a particular party, did they simply name the issues that they thought appropriate given their party choice?

Priorities

Morgan asked respondents not what issues would influence their vote but which of the issues would be ‘most important’ to them. Respondents drawn from four electorates could choose three from a list of six, all of them valence issues: ‘keeping day-to-day living costs down’; ‘improving health services and hospitals’; ‘managing the economy’; ‘improving education’; ‘open and honest government’; ‘reducing crime and maintaining law and order’ − this last an issue regarded traditionally as a matter for state not national governments. Omnipoll, adopting another approach, asked respondents to think about ‘which one of these policies is the most likely to get your vote . . . : more spending on education; a cut to the rate of company tax; reducing the government budget deficit.’ Ipsos asked whether a ‘higher priority’ should be given to ‘more money for schools or cutting tax for business.’ ReachTEL wanted to know whether respondents supported ‘tax cuts for companies’ or ‘increased spending on health and education services’ most.

Perhaps what mattered were not national issues but local issues. Polling in the electorate of Leichhardt, Galaxy wanted respondents to nominate ‘the most important priority for Cairns at the election’. The options, in descending order of support: ‘jobs creation’; ‘building new infrastructure’; ‘reef protection’; ‘highway upgrades’. In Herbert, it wanted to know ‘the most important priority for Townsville’. In descending order of support: ‘water security’; ‘jobs’; ‘infrastructure’; ‘tax cuts’; ‘roads’. Essential attempted to measure the priority of certain issues not for a region but ‘for ensuring Australia grows local jobs’. In this context, it asked respondents to assess the importance of: ‘local jobs and local content rules for government funded infrastructure projects’; ‘better funding of TAFE programs to give people the skills to get the jobs of the future’; ‘government support for local manufacturing industries like the steel industry’; ‘more investment in renewable energy’; ‘opening up investment for foreign companies so they bring the technology and skills to Australia’; ‘tax cuts for large companies’.

Position issues

Relatively few of the questions addressed what Stokes (1966/1963, 170) called ‘position issues’ − issues ‘that involve advocacy of government actions from a set of alternatives’. Of the 151 issue questions, less than 10 per cent were framed as position issues. And though some of the issues that the election was said to be about were raised, others weren’t. One of the issues not raised was the restoration of the Australian Building and Construction Commission, the occasion for the double dissolution.

How many of these questions went to issues of threat or security is moot. Essential asked whether respondents: ‘approve[d] or disapprove[d] of the budget measure . . . to introduce internships for unemployed people which pay $4 per hour for up to 25 hours per week’; approved ‘the $50 billion in tax cuts for medium and large business announced in the Federal budget’; or approved ‘the changes to superannuation made in the Budget, which includes capping tax concessions for those with more than $1.6 million in superannuation’. It also asked: whether the current law under which ‘whistleblowers in government agencies who reveal any information about government decisions and projects may be tracked down by the Australian Federal Police and prosecuted using national security power’ should stay or ‘be limited to leaks of information that harms our national security’; and whether respondents ‘support[ed] or oppose[d] phasing out live exports to reduce animal cruelty and protect Australian jobs’. ReachTEL wanted to know if respondents ‘support[ed] or oppose[d] people who work on Sunday receiving a higher penalty rate than people working on Saturday?’ Ipsos asked about legalising marriage between same-sex couples and about whether the matter ‘should be decided by a parliamentary vote by MPs or a plebiscite of all Australians’. Galaxy asked whether ‘the federal government should contribute a significant share in the construction of a Stadium and Entertainment Centre in Townsville’s CBD’.

For issues to be framed in the form of a referendum, Gallup’s ideal, the framing needed to be binary. Only a few were not. Essential wanted to know which of four actions on climate change, including ‘no action’, respondents would ‘most support’. ReachTEL asked respondents to ‘rate’, on a five-point scale, ‘the quality of the current Medicare system’. And in Tasmania, ReachTEL wanted to know which of the ‘three tiers of government . . . could be best abolished’.

In Britain, questions about issues were more frequent (they accounted for 26 per cent of the all questions asked; 19.1 per cent in Australia), position issues especially so (19.3 per cent of all the issues questions compared to 1.6 per cent in Australia). Position issues, nonetheless, accounted for no more than 5 per cent of all the questions asked in Britain (Goot 2017, Table 7.5); just as many of the issue questions were about vote drivers, a category that accounted for 29.1 per cent of the issue questions in Australia. More of the questions (25.8 per cent) in Britain were about valence issues, as they were in Australia (37.7 per cent). And about a third were about issues of other kinds, including questions about sociotropic and pocketbook issues (Goot 2017, Table 5), issues not raised by any of the polls in Australia.

The campaign

In Australia, the number of questions about the campaign (5 per cent of all the questions asked) was small. Only two pollsters asked questions (Essential) or were instructed by the media to ask questions (ReachTEL) about the campaign.

Some questions were about respondents’ interest in the campaign. Which of four statements, Essential asked, ‘best describe[d] how much political news and commentary’ respondents ‘intended to look at during the election campaign’: ‘I will be looking at a lot of news and commentary as I am always interested in politics’; ‘I’m not usually very interested in politics but will be looking at a lot more news and commentary during the campaign’; ‘I’m not very interested in politics so won’t be reading much more than usual during the election campaign’; ‘I don’t like politics at all and will try to avoid looking at any news and commentary during the election campaign’. Halfway through the campaign it asked: ‘how much interest have you been taking in the news about the campaign and what the parties have been saying?’

Another set of questions sought to document respondents’ exposure to the campaign. Had they: ‘seen TV campaign ads’; ‘received campaign materials in [their] letterbox’; ‘watched one of the party leader debates on TV’; ‘received an email about the election’; ‘visited a website about election issues’; ‘been surveyed on the phone’; ‘had a phone call from a political party’; ‘been approached in the street by party workers handing out material’; ‘been door-knocked by a political party’; ‘been door-knocked by another group (e.g. union, interest group)’? Asked in week four of the campaign, these questions were repeated in week seven.

Other questions asked respondents to evaluate the campaign. Was ‘an 8-week election campaign’, Essential asked shortly after the announcement, too long, ‘too short or about right’? Halfway through the campaign ReachTEL asked respondents how they would ‘rate this election so far in addressing the issues important to you?’ In week seven and again in week eight, Essential asked ‘Which leader and party do you think has [sic] performed best during the campaign: ‘Malcolm Turnbull and the Liberal Party; Bill Shorten and the Labor Party; Richard di Natale and the Greens?’ This was one of the few references in the polls, other than in the voting intention questions, to any of the parties apart from the Liberals, the Coalition and Labor or any party leader other than Turnbull and Shorten. In week six, Essential had asked: ‘which party seems to be making the most spending promises’ and ‘which party seems to be making the most spending cuts’? But the choices each time were restricted to ‘Labor, Liberal, no difference.’

In Britain, the proportion of questions devoted to the campaign was nearly three times as great (9.8 per cent). But without the Opinium polls commissioned by the Observer the amount of polling on the campaign in Britain would have been much reduced (Table 8.3).

Outcomes

What did respondents expect as a result of the election? All the pollsters, other than Morgan, showed an interest in this. Most of the questions focused on one outcome about government − which party, if any, would win; and on one outcome to do with a policy − the fate of Medicare. Questions about the likely winner reflected a longstanding belief among campaigners that ‘win expectations’ influenced the vote. Questions about Medicare picked up on a point of difference between the parties opened up in the course of the campaign by Labor's ‘Mediscare’ – a difference that post-election commentary, though lacking much in the way of evidence, considered nearly decisive (Goot, in press).

Government

‘Regardless of who you will vote for’, Ipsos asked in each of its four polls for Fairfax, ‘who do you think will win the next federal election’, Labor or the Coalition? At the beginning of the campaign and near the end, Newspoll asked: ‘Which political party [the Liberal–National Coalition, the Labor Party] do you think will win the federal election (on Saturday)?’ Towards the end of the campaign and in its final poll, Omnipoll also asked ‘which political party’ or ‘which of the major parties’ respondents thought would ‘win the federal election’ or ‘win the July 2 election’ and named two options − Labor and the Coalition.

Other polls offered a third option. In each of the last two weeks of the campaign Essential asked respondents which party [sic] – the Liberal–National Coalition or the Labor Party − they ‘expect[ed]’ to ‘win the Federal election’, or would ‘neither’ win, leaving a ‘hung Parliament’? ReachTEL, in its last two national polls, also wanted respondents to predict the outcome: a Coalition win; a Labor win; or a hung parliament – though the meaning of a ‘hung parliament’ was left hanging. ‘One possible outcome of the election’, Omnipoll had explained to respondents earlier in the campaign, was ‘a “hung parliament” where neither party has enough seats to form government in its own right.’ ‘The 2010 federal election’, it went on to explain, ‘resulted in a “hung parliament”’. It then asked: ‘If the 2016 election also results in a hung parliament, which of the following do you personally think would be best for Australia: one of the major parties should form government with the Independents or the Greens as happened in 2010; there should be a new election’?

Policy

Other questions focused on likely policy outcomes. Essential wanted to know: which party, Labor or Liberal, ‘would be most likely to reduce Australia’s debt’; whether respondents thought a Labor government ‘would keep the Coalition government’s policy on asylum seekers arriving by boat’ or would Labor ‘change the policy’; and whether it was ‘likely or unlikely’ that the Liberal Party would ‘attempt to privatize [sic] Medicare’ if it won. Medicare was the focus of most of the policy questions. ReachTEL asked whether respondents thought Medicare was ‘more or less likely to be privatized [sic] under a Liberal–National Coalition government than a Labor government’ and later whether respondents ‘believe[d] that Malcolm Turnbull will keep his promise and not privatise Medicare’ − questions prompted by Labor’s claim, in the last weeks of the campaign, that Turnbull would privatise Medicare. ‘Mediscare’ excited the Courier-Mail as well. In six Queensland seats, Galaxy asked whether respondents believed Bill Shorten’s claim that ‘the Coalition wants to privatise Medicare’ or whether it was ‘just a scare campaign’. Later it asked, nationally, whether respondents ‘believe[d] Bill Shorten’s claim that the Coalition intended to privatise Medicare’. It also asked whether respondents ‘believe[d] Malcolm Turnbull’s claim that Labor’s negative gearing policy would drive down house prices’? Essential was the only poll to broach a broader question. Would ‘the result of this election’, it asked: ‘fundamentally change Australia’; ‘have a significant impact on the future of Australia’; ‘have a limited impact on the future of Australia’; ‘have no impact on the future of Australia’?

In Britain, the polls had paid more attention to questions about outcomes; such questions made up 10 per cent of the questions they asked (Table 8.3). The difference is easily explained: the majority of the British questions were about things that the polls in Australia didn’t touch – not which party would win, but which party or parties respondents wanted to see form government (Goot 2017, Table 7.8). In Britain, a hung parliament was widely expected; in Australia, it was not.

Conclusion

Public opinion polls in Australia and in Britain, originally focused on issues – position issues above all – have changed. Today, the press particularly like questions that focus on voting intentions and on the alternative national leaders – polls that inform their audiences, politicians and party managers included, about which party and which party leader is ahead and which of them is behind. In this way they not only report the state of opinion on the ‘horse race’; they also maximise their influence on it. Nowhere was the focus greater on how the parties were faring (the two-party preferred being the key measure) or how the two main leaders were faring (the gap in the preferred prime minister measure) than in the country’s elite press: the Australian, the Australian Financial Review, the Sydney Morning Herald and the Age. All but two of the 66 questions asked on behalf of the Australian – the paper read by all or almost all federal politicians – during the campaign were either about how the country was going to vote or about the alternative prime ministers. Two thirds of the questions asked on behalf of Fairfax were of this kind, too. In Britain, the Guardian focused on voting and leaders (68.9 per cent of the questions asked by ICM were of this kind); but the proportion of the questions asked by Opinium for the Observer and by YouGov for the Times and Sunday Times was not as great (Table 8.3 for the data; Cowley and Kavanagh 2016, 235, for the newspaper links).

The focus of Australia’s elite press on the distribution of party support and the contest between the leaders is not a function of who owns the papers; both the Australian and the Times are owned by News Corp. Nor does it appear to be principally a function of costs; given that Newspoll used a combination of robopolling and polling online, it would have cost the Australian very little more to have had Newspoll add other questions. Rather than being a matter of comparative costs, the differences are more likely to reflect contrasting levels of competition, with Australia’s newspaper market, largely a regional one, being less competitive than Britain’s national market. That the Australian was more focused on the vote and the leaders than any other newspaper might reflect the fact that it has less competition nationally than the Sydney Morning Herald and the Age have locally, with the latter losing circulation at a faster rate than their morning competitors, the Daily Telegraph and the Herald Sun (B&T 2015). No doubt what these papers thought of interest to their readers influenced matters, too.

The ABC’s VoteCompass attempted to keep track of its viewers’ positions on issues, helping those who logged in locate their own positions in relation to those of the parties – inscribing a hyper-rationalist view of politics that made issue positions the beginning and end of political choice – while occasionally, and rather cack-handedly, broadcasting the results. But it is unlikely that this discouraged News Corp or Fairfax from polling on issues, whatever the crossover in audiences.

The production of pre-election polls has spread across the mediascape and beyond. The only campaign polls commissioned for television in Australia prior to the 2010 election appear to have been exit polls (Goot 2012a, 85). In 2016, for every three questions asked for the News Corp or Fairfax papers another question was asked for 7News or Sky News. Between them however, the press and television commissioned less than two thirds of all the questions asked.

The rise of polls that are self-funded is relatively new. In Australia it dates from the aftermath of the 2001 election when the Bulletin cut its ties with Morgan (Goot 2002, 84–88). Morgan’s days of dominance are long gone. Of the two independent polls – Morgan and Essential – it was Essential that proved the much more interesting, readers benefiting from its need to keep its online panel engaged via questions that weren't product-related, the interest among of its social movement clientele in seeing certain issues pursued, and its determination to generate media publicity on its own account. Not only did Essential ask more questions than were commissioned by either News Corp (Galaxy and Newspoll) or Fairfax (Ipsos and ReachTEL); it asked almost as many questions about the parties, issues, campaign and outcomes as all the other pollsters combined. In addition, Essential stood out for the distinctiveness of some its approaches – the use of batteries of questions and the attempt to link parties with groups among them.

The availability of new technologies helps explain why seven firms conducted polls (two online, two online plus robopoll, one robopoll and one via CATI) and why 11 did so in Britain (seven online, four using CATI). The low cost of entry also helps explain why some firms, both in Australia (two) and in Britain (four plus one, Panelbase, in part), were keen to conduct polls even though, at a time when increasingly the commercial media find themselves financially stressed, no newspaper or television station was prepared to pay them. The value of the publicity helps explain why so many pollsters entered the field even if few of them made any money out of it.

Despite the similarities, the contrasts between polling in Australia and in Britain are equally noteworthy. Robopolling, now common in Australia, is almost unheard-of in Britain (Goot 2014, 24–25); where British pollsters have changed their mode of data-gathering it has been from CATI to online, not to robo. The number of polls conducted in Australia was much smaller than the number in Britain, notwithstanding Australia’s much longer campaign. The balance between polls based on a group of constituencies or single seats, on the one hand, and polls conducted across the whole electorate, on the other, was quite different as well. Why the intensity of the polling – the number of questions, on average, in each of the surveys – was much lower in Australia is not clear. Perhaps the more competitive British press has got something to do with it. Perhaps the British media are more prosperous. Or perhaps the British and Australian media have different views about the questions polls need to ask, and of whom they need to ask them, if they are to interest their audience.

What is clear is that the Australian polls placed much more emphasis than the polls in Britain on estimating the vote, notwithstanding that Australian pollsters, unlike British pollsters, don’t have to worry much about measuring the likelihood of their respondents’ actually voting. The polls conducted in Britain placed much more emphasis on ascertaining respondents’ views of the parties, of the campaign and of the election outcomes – the pollsters’ response, perhaps, to the number of British parties likely to win seats; a reflection on the traditional concern in the British polls with measuring campaign involvement (see Goot 2017, 78); and a comment on the range of possible coalitions and other uncertainties surrounding the outcome. In Australia, an interest in how respondents viewed the leaders came second to an interest in how respondents were going to vote. In Britain, interest in the leaders came first.

In both campaigns the polls’ focus on issues was less marked. More remarkable, especially in Australia, was how few of the issue questions were about position issues. It is true that the distinction between valence issues and position issues can be overdrawn: respondents may think one party better than another on an issue precisely because the policy of one party is radically different from the policy of the other. Nonetheless, the very limited attempt by the polling organisations to determine respondents’ issue positions signifies the collapse of the Gallup model, confirming at the national level what was evident already in New South Wales, the most populous Australian state (Goot 2012b, 281). It suggests a change in the view that respondents know enough about the alternatives to have positions on most issues, a decline in the view that the parties themselves have readily distinguishable policy positions, or a shift in the view that media audiences care.

However flawed Gallup’s reasoning about the ability of the polls to convey the electorate’s policy preferences, the reluctance of pollsters to embrace this argument moves the justification for polling in a democracy away from its roots in American progressivism. And it does so at precisely the time when the other and more recent justification for the polls – that they constitute an independent measure of party support against which to assess the integrity of electoral outcomes – has come to be viewed, in many quarters, with increasing scepticism.

Acknowledgement

Research for this chapter was funded by the Australian Research Council’s Discovery Project 150102968. For his perspicacious comments on earlier drafts and for his persistence I am grateful to Shaun Wilson.

References

Achen, Christopher H. and Bartels, Larry M. (2016). Democracy for realists: why elections do not produce responsive government. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

APOP (1943a). Australian Gallup polls, ‘Australia speaks’ – Nos 132–40. Published July 1943.

APOP (1943b). Australian Gallup polls, ‘Australia speaks’ – Nos 141–52. Published August–September, 1943.

B&T (2015). Newspapers: our breakdown of the latest ABCs. B&T Magazine, 13 November. http://www.bandt.com.au/media/newspapers-our-breakdown-of-the-latest-abcs.

Cowley, Philip and Dennis Kavanagh (2016). The British general election of 2015. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Gallup, George and Saul Forbes Rae (1940). The pulse of democracy: the public-opinion poll and how it works. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Goot, Murray (in press). National polls, marginal seats, and campaign effects. In Double dissolution: the 2016 federal election, Anika Gauga, Ariadne Vromen, Peter Chen and Jennifer Curtin, eds. Canberra: ANU E-Press.

Goot, Murray (2017). What the polls polled: towards a political economy of British election polls. In Political communication in Britain: polling, campaigning and media in the 2015 general election. Dominic Wring, Roger Mortimore and Simon Atkinson, eds. 77–111. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Goot, Murray (2015). How the pollsters called the horse-race: changing technologies, cost pressures, and the concentration on the two-party preferred. In Abbott’s gambit: the 2013 election. Carol Johnson and John Wanna (with Hsu-Lee), eds. 123–42. Canberra: ANU E-Press.

Goot, Murray (2014). The rise of the robo: media polls in a digital age. In Australian Scholarly Publishing’s essays 2014: politics, 18–32. North Melbourne: Australian Scholarly Publishing.

Goot, Murray (2012a). To the second decimal point: how the polls vied to predict the national vote, monitor the marginals and second-guess the Senate. In Julia 2010: the caretaker election. Marian Simms and John Wanna, eds. 85–110. Canberra: ANU E-Press.

Goot, Murray (2012b). The polls and voter attitudes. In From Carr to Keneally: Labor in office in NSW, 1995–2011. David Clune and Rodney Smith, eds. 270–81. Sydney: Allen & Unwin.

Goot, Murray (2002). Turning points: for whom the polls told. In 2001: the centenary election. John Warhurst and Marian Simms, eds. 63–92. St Lucia: University of Queensland Press.

Irvine, Jessica (2017). High anxiety: Trump is officially scary. Sydney Morning Herald, 6 February.

Madigan, Lee (2014). The hard sell: the tricks of political advertising. Carlton: Melbourne University Press.

Muir, Kathie (2008). Worth fighting for: inside the Our Rights at Work campaign. Sydney: UNSW Press.

Stokes, Donald E. (1966/1963). Spatial models of party competition. In Elections and the political order. Angus Campbell, Philip E. Converse, Warren E. Miller and Donald E. Stokes, eds. 161–79. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Sturgis, Patrick, Nick Baker, Mario Callegaro, Stephen Fisher, Jane Green, Will Jennings, et al. (2016). Report of the inquiry into the 2015 British general election opinion polls. London: Market Research Society and British Polling Council.