2

Study area and methodology

Location

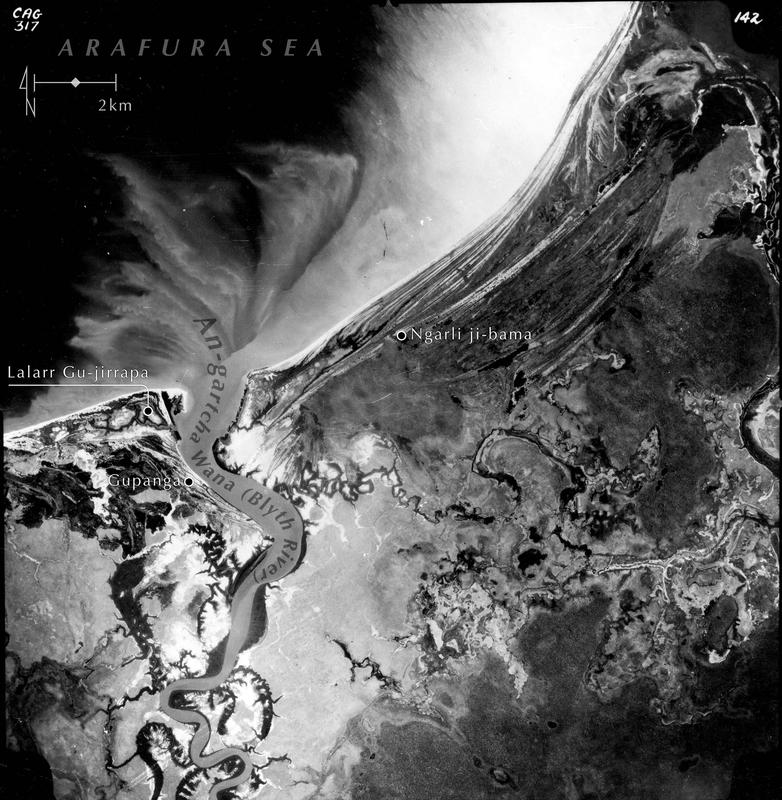

An-gartcha Wana is located on the coastal plains of northern Australia, 12 degrees south of the Equator in a subtropical savanna environment, in the “Top End” of the NT. The river rises in the Arnhem Land plateau to the south and flows into Boucaut Bay in the Arafura Sea. The study area is located 40 km east of the township of Maningrida in central Arnhem Land. It is bounded by the Arnhem Land escarpment to the south, the Arafura Sea to the north, the Liverpool River to the west and Cape Stewart to the east (Map 1.1, Figure 2.1; Meehan 1982a, 10–11).

Figure 2.1 Aerial view of An-gartcha Wana.

Climate and landscape change during the mid to late Holocene

As in other parts of the northern coastal plains, following the Last Glacial Maximum, down-cut river valleys of Arnhem Land were drowned during post-Pleistocene sea-level rise, which flooded the Torres Strait and cut off New Guinea from Australia c. 12,000 years ago (Williams et al. 2018). Although there are common elements, the environmental histories of each region in the Top End are governed by catchment size, tides, sediments and local features of the topography, which can differ considerably, affecting aspects of the cultural landscape (Brockwell 2001).

A warmer and wetter period occurred between about 9,000 to 6,000 years BP (Reeves et al. 2013; Rowe et al. 2019; Williams et al. 2015). During this time, processes of sedimentation following sea-level stabilisation in the mid Holocene formed vast mangrove swamps in the estuarine systems of the Top End, including An-gartcha Wana, from about 7,000 to 4,000 years BP, the “Big Swamp” Phase (Chappell 1988, 2001; Chappell & Woodroffe 1985; Hope et al. 1985; Woodroffe 1988; Woodroffe et al. 1985).

Northern Australia appears to have become drier during the mid to late Holocene, with studies drawing a possible link to the emergence of enhanced El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) conditions between c. 5,000–2,000 years BP (McGowan et al. 2012; Williams et al. 2015). The mid to late Holocene was punctuated by millennial-scale variability, associated with ENSO, which is evident in the marine, coral, speleothem and pollen records of the region (Reeves et al. 2013; Rowe et al. 2019; Stevenson et al. 2015).

This drier period in northern Australia led to the formation of chenier ridges, elongated deposits made up of sand and shell, on mudflats and saline tidal flats, which initiated chenier-building and coastal progradation (Clark & Guppy 1988; Mulrennan & Woodroffe 1998; O’Connor & Sullivan 1994; Woodroffe et al. 1985). In the Top End, siltation and coastal progradation reduced the extent of tidal influence and the mangroves retreated towards the coast and the edges of waterways, and saline mudflats were formed. As high-tide flooding became rarer, brackish and freshwater swamps formed in residual depressions on the landward edge of the coastal plains. This “Transition” Phase occurred between 5,000 and 2,000 years BP, depending on the river system (Chappell 1988, 2001; Clark & Guppy 1988; Hope et al. 1985), and coincides with the onset of ENSO.

Climate amelioration was brought about by more pervasive La Niña conditions post-2,000 years BP (Williams et al. 2015). Freshwater from monsoon rains ponded behind the cheniers, and freshwater wetlands became widespread after 2,000 years on the floodplains of the Top End. This is called the “Freshwater” Phase (Chappell 1988; Clark and Guppy 1988; Hope et al. 1985; Mulrennan and Woodroffe 1998; Woodroffe 1988).

Geomorphology on the floodplains of An-gartcha Wana

John Chappell and Rhys Jones (1999) undertook geomorphological fieldwork to obtain core samples in collaboration with the An-barra community, especially Betty Ngurrpangurrpa and Ranger Stewart Rankin. This work, along with the radiocarbon dates from the geomorphological research, has enabled the archaeological data to be linked to the background environmental data and chronology concerning the evolutionary sequence common to the floodplains of northern Australia in the mid to late Holocene.

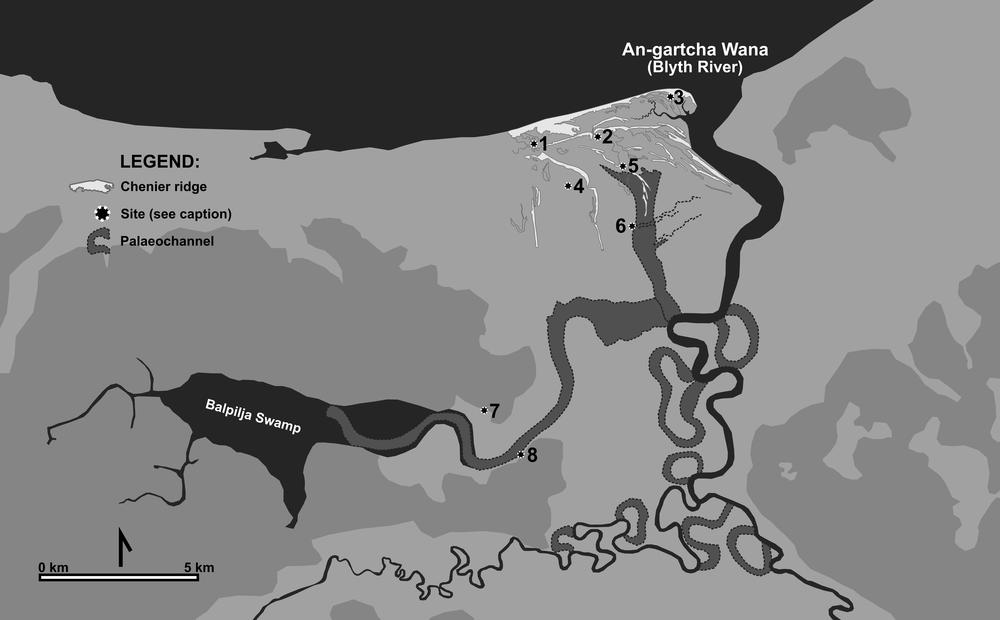

The following information is based on their field notes. Dating samples were taken from cores at eight locations from the coast to Balpilja Swamp. The geomorphological sites are, from the sea inland:

- Jinawunya

- Gulukula

- Lorrkon a-jirrapa

- An-mal Mandayerra

- Ngalpura Jinyu-nirripa 2

- Ngalpura Jinyu-nirripa 3

- Ji-bena

- Anamanba

Several of these sites have the same location as the archaeological sites described in the next chapter (Map 2.1). Due to coastal progradation in the late Holocene, the closer to the coast, the younger the dates (Tables 2.1 and 2.2). A limitation of these data is that we cannot establish from Jones and Chappell’s notes whether some of the geomorphological dating samples were on shell or charcoal. Nor did they record which radiocarbon laboratory did the dating. Therefore, three of the radiocarbon dates from two sample sites (Ngalpura Jinyu-nirripa 2 and 3) were calibrated with OxCal (Bronk Ramsey 2024) using both the Marine20 (Heaton et al. 2020) and the SHCal20 calibration curve (Hogg et al. 2020). The local marine ΔR has been determined via Ulm et al. (2023) using approximate site coordinates (decimal latitude/longitude).

Map 2.1 Geomorphological sample sites: 1. Jinawunya; 2. Gulukula; 3. Lorrkon a-jirrapa; 4. An-mal Mandayerra; 5. Ngalpura Jinyu-nirripa 2; 6. Ngalpura Jinyu-nirripa 3; 7. Ji-bena; 8. Anamanba (Billy Ó Foghlú).

| Site (no. Map 2.1) | Lab. Code | Age C14 | Local Marine ΔR | Cal. Curve | Age cal BP 2σ |

Cal. Curve | Age cal BP 2σ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Big Swamp Phase | |||||||

| Ngalpura Jinyu-nirripa 3 (6) | Blyth 1399 | 7890±210 | -141±36 | Marine 20 | 8922–7880 | SHCal 20 | 9291–8209 |

| Anamanba (8) | Blyth 1599 | 5656±202 | -141±36 | - | - | SHCal 20 | 6891–5940 |

| Ji-bena 1999 (7) | Blyth 1199 | 4980±170 | -141±36 | - | - | SHCal 20 | 6175–5312 |

| Ngalpura Jinyu-nirripa 3 (6) | Blyth 1299 | 3970±90 | -141±36 | Marine 20 | 4287–3681 | SHCal 20 | 4795–4090 |

| Transition/Chenier-Building Phase | |||||||

| An-mal Mandayerra (4) | Blyth 799 | 3840±220 | -140±36 | - | - | SHCal 20 | 4833–3639 |

| Ngalpura Jinyu-nirripa 2 (5) | Blyth 899 | 2510±210 | -141±36 | Marine 20 | 2728–1661 | SHCal 20 | 3058–2010 |

| Freshwater/Chenier-Building Phase | |||||||

| Lorrkon a-jirrapa 1999 (3) | Blyth 399 | 2040±80 | -141±36 | Marine 20 | 1839–1355 | - | - |

| Jinawunya 1999 (1) | ANU-11207 | 1530±60 | -140±36 | Marine 20 | 1264–887 | - | - |

| Gulukula 1999 (2) | Blyth 199 | 1420±60 | -140±36 | Marine 20 | 1150–750 | - | - |

| Calibrations performed via OxCal 4.4.4 [173] (Bronk Ramsey 2009, 2024) using Marine20 (Heaton et al. 2020) or SHCal 20 (Hogg et al. 2020). The local marine ΔR has been determined via Ulm et al. (2023) using approximate site coordinates (decimal lat/long). | |||||||

Table 2.1 An-gartcha Wana geomorphology dates.

| Site (no. Map 2.1) | Lab. Code | Substrate | Sample | Location | Depth (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Big Swamp Phase | |||||

| Ngalpura Jinyu-nirripa 3 (6) | Blyth 1399 | Blue, grey mangrove mud, sparse organics & broken shell | ? | End of ridge | 250 |

| Anamanba (8) | Blyth 1599 | Black swamp clay, over red-mottled clay, over light grey clay with organics | Charcoal | Eleocharis swamp at margin of Balpilja palaeochannel | 30–80 |

| Ji-bena 1999 (7) | Blyth 1199 | Dark grey mangrove mud with organics | Charcoal | Palaeochannel | 240 |

| Ngalpura Jinyu-nirripa 3 (6) | Blyth 1299 | Blue, grey mangrove mud, sparse organics & broken shell | ? | End of ridge | 180 |

| Transition/Chenier-Building Phase | |||||

| An-mal Mandayerra (4) | Blyth 799 | Clay with organics | Charcoal | Under ridge | 270 |

| Ngalpura Jinyu-nirripa 2 (5) | Blyth 899 | Yellow, mottled grey clay | ? | Under ridge | 150 |

| Freshwater/Chenier-Building Phase | |||||

| Lorrkon a-jirrapa 1999 (3) | Blyth 399 | Shelly sand | Shell | Chenier base | 240–250 |

| Jinawunya 1999 (1) | ANU-11207 | Grey mud | Dosinia juvenilis | Next to well | 40 |

| Gulukula 1999 (2) | Blyth 199 | Shelly sand | Shell | Chenier next to shell mound | 145 |

Table 2.2 An-gartcha Wana geomorphology phases.

Balpilja Swamp was previously an ancient valley drowned during early Holocene sea-level rise. Chappell predicted that the formation beneath the swamp dates to the late Pleistocene. He estimated that the eastern part of Balpilja formed a palaeo- estuary some 6,000–7,000 years ago. Today, Balpilja is a freshwater swamp lying 8 km from the coast, indicating the extent of coastal progradation over the mid to late Holocene.

The Ngalpura Jinyu-nirripa chenier ridge lies approximately 3 km inland from the coast (Map 2.1). The core at Ngalpura Jinyu-nirripa 3 was taken from under the ridge at 2.5 m and is the oldest dated geomorphological site on the An-gartcha Wana floodplains. The blue, grey mangrove mud from the sample dates the Big Swamp Phase here from 9,291–7,880 cal BP (Blyth 1399).

At Anamanba, next to the archaeological site of the same name described in the following chapter, light grey clay with organics taken from an Eleocharis swamp next to Balpilja palaeochannel were dated to 6,891–5,940 cal BP (Blyth 1599). In the palaeochannel next to Ji-bena, where the archaeological site is also located, the Big Swamp Phase was dated to 6,175–5,312 cal BP (Blyth 1199). Mangrove mud from another sample taken at 180 cm from Ngalpura Jinyu-nirripa 3 shows that the Big Swamp Phase persisted at least until 4,795 cal BP (Blyth 1299) on the An-gartcha Wana floodplains (Table 2.2). During this period, the coast was further inland and the Balpilja palaeo-estuary was active until c. 6,000–7,000 years BP (Map 2.1).

During the following Transition Phase, the drier climate initiated chenier-building and coastal progradation was pronounced in the region. At An-mal Mandayerra, this phase was dated to 4,833–3,639 cal BP (Blyth 799) from a sample 2.7 m below the surface. This phase persisted until at least 3,058–1,661 cal BP (Blyth 899), based on a sample taken at 1.5 m at Ngalpura Jinyu-nirripa 2 (Map 2.1, Table 2.2). The radiocarbon chronology shows that the coastline advanced rapidly seaward at up to 50 m per century in the last 2,000 years (Chappell & Jones 1999, 93). The near-coastal cheniers are all less than 2,000 years old and track the advancing coastline. The sample from the base of Lorrkon a-jirrapa chenier 3 km inland, next to the archaeological site of the same name, dates to 1,839–1,355 cal BP (Blyth 399) (Map 2.1, Table 2.2). The Gulukula chenier, next to the shell mounds of the same name, lies approximately 1 km inland. A sample taken from 1.45 m dates from 1,150–750 cal BP (Blyth 199). The Jinawunya chenier, which is associated with the archaeological site, is closest to the coast and was dated 1,264–887 cal BP (ANU-11207). The coastline continued to prograde, as Betty noted from comparing aerial photographs of the Blyth River mouth in 1958 and 1968 (Meehan 1982a, 15).

With increasing rainfall and sedimentation in the last 2,000 years, large mangrove swamps behind the cheniers became freshwater wetlands. It was during this Freshwater Phase that Balpilja Swamp next to Ji-bena mound became freshwater (Table 2.2; Brockwell 2013; Chappell & Jones 1999; Thurtell et al. 1999). The geomorphological evidence and dates show that the evolution of the An-gartcha Wana landscape is recent and conforms with that of other river systems of the Top End. The alluvial and coastal systems are still actively changing (Thurtell et al. 1999, 8). The An-barra are keenly aware of their mobile landscape with dune build-up, storm erosion, shifting mangroves and river channels. These memories are preserved in their mythology, and they treat such changing areas with respect in the hopes they will remain stable (Meehan 1982a, 15–16).

Climate and landscape today

Today, the coastal plains of northern Australia lie within the dry tropics. The climate is markedly seasonal with a long dry season, dominated by southeast trade winds, lasting roughly from May to November, and a shorter wet season from December to April, dominated by the northwest monsoon (Christian & Stewart 1953, 29). This cycle is reliable from year to year in the Top End, a feature that distinguishes it from regions further to the south where it can be unreliable (McDonald & McAlpine 1991, 19). Rainfall is high in the wet season with an average of 1,291 mm per annum at Maningrida, most of which occurs between December and March (Thurtell et al. 1999, 9). The average daytime temperatures remain stable throughout the year, ranging from 30.1°C in July to 33.4°C in November. More significant in terms of human comfort are the variations in night-time temperatures, averaging from 17.2°C in July to 25.1°C in December, and the relative humidity, which builds up from September and remains high throughout the wet season (Bureau of Meteorology 2024). The most stressful time of year is the late dry season, October through December, when both day and night-time temperatures are high, and the humidity builds up often without the relief of rain.

The hydrology of the coastal plains of northern Australia is regulated by its strongly monsoonal climate. The groundwater builds up in the wet season and maximum run-off occurs late in the season (Chappell & Woodroffe 1985, 90). Floodplain areas are inundated during the wet season making many places accessible only by watercraft. These areas dry out progressively through the dry season. By the late dry season most of the floodplains have dried out, except for low-lying areas which remain submerged for most or all the year.

The land owned by the An-barra has been described in detail by Meehan (1982a). In brief, after An-gartcha Wana leaves the escarpment, it flows across savanna plains through dry Eucalyptus tetradonta woodland. Within 40 km of its mouth, it joins the Cadell River and becomes tidal and brackish. The coast is a soft shore with sandy mudflats and little or no offshore reefs. This environment limits the diversity of shellfish species available. The land surrounding this area supports a mosaic of productive habitats, including freshwater wetlands, mangroves, monsoon rainforest and pandanus groves (Map 2.2; Meehan 1982a, 10–12).

Map 2.2 Environmental zones (Adam Black).

Within this rich environment of sea, estuary and freshwater wetlands, there are abundant seasonal food resources available to the An-barra, including shellfish, fish, crabs, stingrays, turtles, reptiles (including crocodiles), buffalo, wallaby, birds (especially geese), a great variety of fruits and vegetables, and small delicacies such as honey and mangrove worms. Most of these items were eaten by the An-barra while Rhys and Betty were living with them on their own land and have been previously described in detail (Jones 1980; Jones & Meehan 1989; Meehan 1982a, 1982b). Shellfish are particularly relevant to archaeology as shells are the most likely remains to survive in archaeological sites (see Appendix 2 for a list of shellfish species and their habitats). While Rhys and Betty lived with them in the 1970s, the An-barra also had access to European food, mainly tea, sugar and flour.

Methodology

Archaeological fieldwork

Most of the fieldwork for the An-barra Archaeological Project was undertaken by Betty Meehan and Rhys Jones between 1972 and 1980, as detailed in Betty’s book Shell Bed to Shell Midden (Meehan 1982a, 162–8). There are three main types of archaeological sites: shell middens, shell mounds and earth mounds (gun-gapula).

Shell middens

A shell midden has been defined as “an archaeological deposit consisting primarily of mollusc shells resulting from food procurement activities” (Bahn 1992, 453). Bourke (2012, 28) elaborates on middens in the Darwin region:

Shell middens…are deposits containing more than (an estimated) 50% by weight of shells, occurring somewhere in the open, near a beach or estuary or rocky shoreline, or an inland lake or river. These shells have been deposited by humans exploiting marine, estuarine and riverine resources. Middens may take the form of a thin layer of shell over, or just below (subsurface), the land surface, or a thick mound of shell… [They] are usually circular, but may also be elongated or irregular in shape, or doughnut-shaped (shell rings) around a central area containing little or no shell. Unstratified surface scatters of shell also occur.

Meehan (1982a, 166) describes shell middens as “one of the common features of An-barra territory, both inland and on the coast, and they occur in many forms ranging from thin scatters to dense layers of shell up to one metre thick”.

Shell mounds

Meehan (1982a, 167) describes shell mounds in An-barra country as “[l]arge discrete mounds of shells measuring anything up to 5 m in height to 30 m in diameter [that] are dramatic features of the Blyth River landscape. The mounds do not occur on the coast but inland at least 1 km on a series of fossil dunes. They are found on both sides of the river in Anbarra, Gulala and Matai territory.”

Earth mounds

Brockwell (2006, 47) defines earth mounds as “sites that are composed mostly of soil and sand. Depending on their location, they may also contain stone artefacts and faunal remains, including shell.”

Field trips to Maningrida in the 2000s

In the 2000s, Betty and Sally travelled to Maningrida twice. The aim of the first trip, from 4–7 August 2003 and funded by AIATSIS, was to introduce Sally to members of the An-barra Aboriginal community. Sally had already met Betty Ngurrpangurrpa when she came to Canberra for the launch of the book and CD, People of the Rivermouth (Gurrmanamana et al. 2002), but it was important that other members of that community were able to meet and talk with her as well. We stayed in the Maningrida Progress Association’s motel. Many An-barra people now reside more or less permanently in Maningrida, so Sally was able to meet many of them there. Many of these people were children when Betty and Rhys carried out work at the An-gartcha Wana during the 1970s. Most of them now have their own households and many children. While at Maningrida, we were also able to visit the graves of recently deceased An-barra people, most significantly those of Frank Gurrmanamana and his daughter Nancy Djinbor, both of whom died in 2003.

Eventually, we were able to hire a four-wheel drive vehicle so that we could visit Gupanga and Ji-bena where Sally visited the sites Betty and Rhys excavated in 1978 and 1979. Two sites, adjacent to Gupanga on the western bank of the An-gartcha Wana, Muyu a-jirrapa linear midden and Muyu a-jirrapa mound, unfortunately no longer exist. They have been eroded away by the wet season flooding of An-gartcha Wana. However, Sally was able to inspect the surrounding environment to get some idea of the physical context of these important sites. Ji-bena mound is situated some 8 km from the coast on the banks of the freshwater Balpilja Swamp and remains in good condition. While at Ji-bena, we were also able to visit the grave of Nancy Bandeiyama with whom Betty had worked since 1958.

More recently, we visited Maningrida from 10–14 August 2015, this time accompanied by ANU doctoral student Bethune Carmichael who was conducting fieldwork with rangers from the Djelk Indigenous Protected Area. Betty Ngurrpangurrpa and her husband, Dominic Mason, again guided us on their land. We visited the Gulukula shell mounds and the coastal site of Jinawunya (Figure 2.2). Betty Ngurrpangurrpa was interviewed by Bethune Carmichael (2015) for his video, Places in Peril – Archaeology in the Anthropocene, in which she described the destruction of the coastal midden at Jinawunya by wave action. With Betty’s and Dominic’s permission, we took a shell sample to date this site (see Chronology next chapter). We also collected from the beach a selection of shellfish species that are eaten by the An-barra today and in the recent past. These species also occur in the archaeological assemblages. They will be used for stable isotope analysis to examine potential changes in sea surface temperature in the late Holocene, a study being undertaken by Dr Mirani Litster and Dr Ian Moffat (Flinders University). Our discussions with Betty Ngurrpangurrpa indicated that she and other members of her community are pleased that we are working on these sites and look forward to receiving the results.

Figure 2.2 Maningrida visit 2015 (Bethune Carmichael).

Darwin

In Darwin, also in 2015, we were able to talk to various people about our work and obtain relevant comparative material. We met with Dr Patricia Bourke from the Centre for Indigenous Natural and Cultural Resource Management at Charles Darwin University. She has carried out extensive archaeological work on shell mounds in the Darwin region (Bourke 2012) and the results of her project are relevant to our research at An-gartcha Wana. We also held discussions with Dr Christine Tarbett-Buckley (former Head of Collections at the MAGNT) about the possibility of placing archaeological material from our project with that institution when our analysis was complete. Betty had been negotiating with Dr Tarbett-Buckley for some time about donating a collection of An-barra material culture that she and Rhys accumulated during their fieldwork in the 1970s, which was eventually donated to MAGNT in 2015. It seemed appropriate that the archaeological material should be housed in the same place. In 2018, Betty and Sally repatriated the An-barra archaeological collection to MAGNT.

Excavations and laboratory analysis

The sampling and excavation methods employed by Betty and Rhys at each site are detailed in the following chapter under the site descriptions. Sometimes, the deposit was sieved on site; other times, a solid sample was taken. In the latter case, this sample was weighed and sieved at ANU through 1.5 mm mesh and its contents analysed.

As field bucket weights for the deposit from excavations were not recorded, the weight of deposit has been estimated at 1,500 kg per cubic metre (Jones & Johnson 1985, 183). On this basis, we were able to calculate the minimum number of individuals (MNI) of shells per kg of deposit, so that results from each spit could be compared over time. In other cases, where the size and weight of a sample is unknown, just the MNI of the shellfish species is listed.

Most of the assemblages consisted of shell, both marine and estuarine. In the field, shellfish were originally identified by the An-barra themselves (Appendix 2). For her PhD analysis, Betty had shellfish identified by Dr Philip Colman and Dr Winston Ponder of the Australian Museum (Meehan 1982a, ix). Rhys and Freda Stewart (Department of Prehistory, Research School of Pacific Studies, ANU) did some initial MNI analysis of shell assemblages, and these counts were published by Meehan (1982a, 166–8). Later identifications were undertaken at ANU by Sally and Dr Ella Ussher. They used the shellfish reference collection in ANH, Betty’s own identified specimens from An-gartcha Wana, and identifications by Dr Richard Willan.

Identification was not attempted on shell fragments less than 3 mm. Unidentified fragments were bagged, weighed and labelled “Unidentified Shell”. MNI, NISP (number of identified specimens) and weight were calculated for identified specimens. MNI was estimated mostly by the spire in gastropods, e.g. Telescopium and Terebralia, and the umbo or hinge in bivalves, e.g. Geloina, Marcia and Tegillarca (Bourke 2012; Claassen 1998). The molluscan taxa were mostly identified to genus level, but in some cases to species level, e.g. Dosinia juvenilis.

Other faunal material (mainly turtle and fish) and stone artefacts were present in some sites. Fish and turtle were identified by Sally Brockwell to species level where possible using the comparative faunal collections in ANH and MAGNT. Humanly introduced stone was classified according to raw materials (mainly chert and quartzite) and degrees of modification. All data were recorded on laboratory forms and entered onto an Access database, designed specifically for this kind of analysis, and processed in Excel.

The results of the analysis are detailed in the following chapter. All these assemblages are stored at MAGNT and are available for future, more detailed analysis, such as species richness, representativeness, taxonomic evenness, taxonomic heterogeneity and more comprehensive MNI analysis (Faulkner et al. 2021; Harris et al. 2015; Ortiz-Burgos 2016).

Presentation of results

The latter part of the project consisted of writing up results for publication and producing a community report. The extensive field journals of Betty and Rhys and their many publications on the area (e.g. Fullagar et al. 1999; Jones 1980, 1983, 1985b; Jones & Bowler 1980; Jones & Meehan 1989; Meehan 1982a, 1982b, 1983, 1988a, 1988b, 1991, 1995; Meehan & Jones 1980, 1986, 2005; Meehan et al. 1979, 1999) were used to establish the background of the research. Throughout the project, Betty has provided information regarding the social context. She has also provided most of the photographs used in the publication.

Initial outcomes from the An-barra Archaeological Project were presented in several ways. Betty published preliminary findings in 1995 (Meehan 1995). Betty and Sally gave a paper on the archaeology of the Ji-bena mound and the geomorphology of An-gartcha Wana at the Australian Archaeological Association (AAA) conference in Jindabyne in 2003. A research report detailing the findings of the archaeological analysis was published in the AIATSIS journal Australian Aboriginal Studies (Brockwell et al. 2005). Sally presented a paper on the dating of the archaeological sites at the AAA conference in Beechworth in 2006, along with Dr Patricia Bourke (CDU), and at AAA in Adelaide in 2009. The results of these studies were published in two papers on the Holocene settlement of the NT coastal plains (Brockwell et al. 2011, 2013). Sally also published a paper on the An-barra archaeological sites and ethnographic analogy (Brockwell 2013). Chapter 5 contains a plain language report for the An-barra community in English and Gu-jingarliya.