3

What is the risk of being diagnosed with prostate cancer?

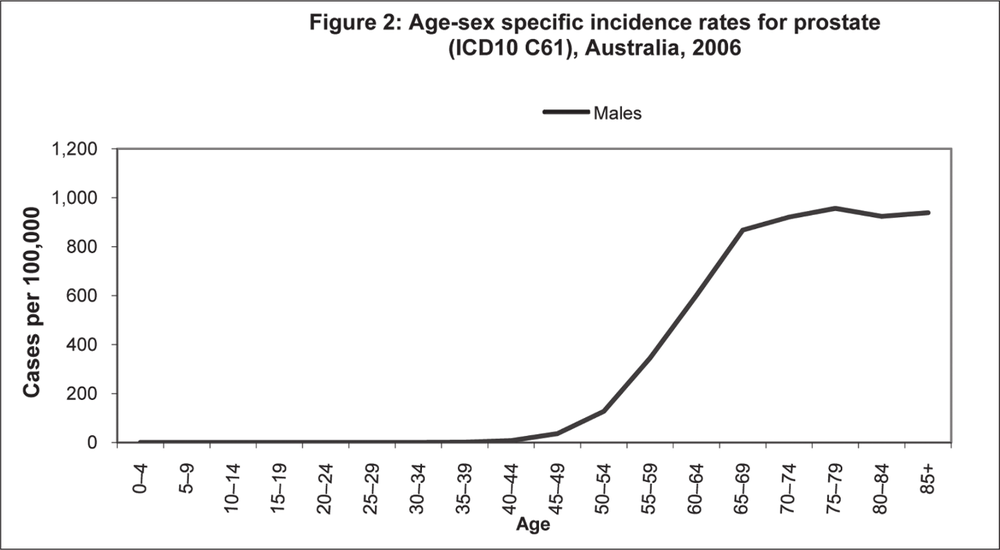

Just as the risk of dying from prostate cancer increases as men age, so does the risk of being diagnosed with prostate cancer (i.e. its incidence). This is clear in Figure 2 below, which shows that prostate cancer is very rare in men under 40 but rises steadily with age from around the age of 40 to around the age of 70 when the incidence curve flattens out.

Advancing age is the most important risk factor for death from nearly every disease. Except for certain illnesses of infancy and childhood, and road deaths (which peak in people in their 20s), nearly every cause of death is far more common in older than younger people. The same is very true for prostate cancer. In Table 2, we saw that the average age that men died from prostate cancer in Australian in 2007 was 79.8, quite easily the oldest average age from death from any of the major causes of cancer death shown. All the other causes of cancer death kill men on average some seven to eleven years earlier. Table 5 shows both the number of men diagnosed in 2005 in each age group, and the age-specific rate of prostate cancer diagnosis per 100,000 men in each age group. 40

Source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2010. ACIM (Australian Cancer Incidence and Mortality) Books. AIHW: Canberra

41Of the 17,444 cases of prostate cancer diagnosed in 2006, just 329 (1.9%) occurred in men aged less than 50. By contrast, 11,079 (63.5%) were in men aged 65 and over. Adjusted for the number of men in each age band, Table 5 shows that the likelihood of a man aged 75–79 (where the odds are highest) being diagnosed as having prostate cancer in one year is one in 232, some 227 times more likely than a man aged 40–44, where the disease is uncommon, and 4274 times more than a man aged 30–34, where the disease is extremely rare. The probabilities of any man aged less than 40 being diagnosed with prostate cancer are thus far lower than those of winning first prize in a lottery where 200,000 tickets are typically sold. These are astronomically low odds. The rate at which men aged 40–44 are being diagnosed with prostate cancer is one in 52,632 and from age 45–49, one in 6,250 – still a very low risk.

Table 5: Number and rate of prostate cancer diagnoses, different age groups, Australia 2005.

| Age-group and number of prostate cancer diagnoses | Rate per 100,000 men | Age-group and number of prostate cancer diagnoses | Rate per 100,000 men |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20–24: 1 | 0.1 (1 in 1 million) | 55–59: 2037 | 164.5 (1 in 608) |

| 25–29: 0 | 0 (–) | 60–64: 2572 | 274.5 (1 in 364) |

| 30–34: 1 | 0.1 (1 in 1 million) | 65–69: 3141 | 412.0 (1 in 243) |

| 35–39: 3 | 0.2 (1 in 500,000) | 70–74: 2672 | 427.0 (1 in 234) |

| 40–44: 29 | 1.9 (1 in 52,632) | 75–79: 2372 | 431.9 (1 in 232) |

| 45–49: 235 | 16.0 (1 in 6250) | 80–84: 1474 | 372.5 (1 in 268) |

| 50–54: 803 | 60.0 (1 in 1667) | 85+: 988 | 323.8 (1 in 309) |

Source: d01.aihw.gov.au/cognos/cgi-bin/ppdscgi.exe?DC=Q&E=/Cancer/australia_age_specific_1982_2005

42Yet in 2010, the Prostate Cancer Foundation of Australia ran TV advertising featuring several Australian male sporting and acting celebrities in their 30s saying to camera that every year prostate cancer kills men “just like me”. As we saw in Table 2, in 2007 there were no cases of men “just like them” in their 30s who died of prostate cancer in Australia. Many young men seeing these advertisements with the rapid cavalcade of highly recognisable men in their 30s and 40s, would assume that it was common for men of this age to die of prostate cancer. This is a highly misleading message.

The chance of having prostate cancer diagnosed depends not only on age but on the extent to which men voluntarily come forward to be tested to see if they have the disease. What we know is that the more we look for prostate cancer, the more we will find. So the lifetime odds of a man being diagnosed depend very strongly on the extent to which men come forward to be tested. If few come forward, far fewer will be diagnosed and so the probability of any man in the community getting a diagnosis will be lower.

As we saw before, if a man was to conscientiously get PSA tested every year from (say) age 50, we know from autopsy studies that about 12% of men in their 40s, and around 40% of men in their 70s [42] could be found to have the disease, if only we looked carefully enough for it. There is a huge reservoir of prostate cancer in the community that could be found if we test enough people, often enough. If those promoting testing are successful, many more men could be diagnosed with prostate cancer and thereafter have to live with this knowledge. Many would undergo traumatic surgical intervention which may profoundly affect their lives. But because the death rates from prostate cancer have barely changed in nearly 40 years, what would have been the point in all this early disease finding? 43

In 2009, the Urological Society of Australia called for all men in their 40s (and over) to get themselves tested. So far, no group of urologists or prostate screening advocates have called for men under 40 to be screened, but by the same “finding a needle in a haystack” reasoning behind the call to screen 40–50-year olds, it may not be inconceivable that someone will reduce the recommended testing age even lower.

By spreading concern and some anxiety to men in their 40s about the disease, a large number might get tested, to the obvious financial benefit of the diagnostic industries concerned. As we will see later in the book (see p81) such testing will result in a large number of men having their prostates surgically removed, and a significant proportion of these men having serious and lasting side effects of that surgery such as sexual impotence.

Why are we seeing increases in prostate cancer in Australia?

Today, after non-melanoma forms of skin cancer, prostate cancer is easily the most commonly diagnosed cancer in Australia. As can readily be seen in Table 6, since 1988 there have been a series of dramatic increases in the number of newly diagnosed cases of prostate cancer in Australia, most particularly between 1988 and 1994, and 2002–2004. The 41% leap in cases between 1992 and 1993 was unprecedented. On the surface, some people would be tempted to look at this data and assume there has been a growing epidemic of prostate cancer in Australia.

However, Australia’s experience mirrors that of many countries where the incidence of prostate cancer diagnosis rose after the introduction and promotion of the Prostate Specific Antigen (PSA) test in 1987–88. No-one knowledgeable about cancer would argue that these rapid rising numbers means that the “actual” incidence of prostate cancer is rising: it is not like the growth of obesity in recent decades. There is not actually more prostate cancer in the 44community. What the rises mean is simply that more men are being tested and because of this, more cancer is being found.

Table 6: New cases of prostate cancer, Australia 1982–2005 (percentage change from previous year)

| 1982: 3680 | 1995: 12369 (–5.4) |

| 1983: 3744 (+1.7) | 1996: 10304 (–16.7) |

| 1984: 3884 (+3.7) | 1997: 9993 (–3.0) |

| 1985: 4156 (+7) | 1998: 10087 (+1.1) |

| 1986: 4306 (+3.6) | 1999: 10581 (+4.9) |

| 1987: 4563 (+6) | 2000: 10835 (+2.4) |

| 1988: 4767 (+4.5) | 2001: 11389 (+5.1) |

| 1989: 5301 (+11.2) | 2002: 12177 (+6.9) |

| 1990: 6109 (+15.2) | 2003: 13774 (+12.9) |

| 1991: 6755 (+10.6) | 2004: 15898 (+15.4) |

Sources: d01.aihw.gov.au/cognos/cgi-bin/ppdscgi.exe?DC=Q&E=/Cancer/australia_age_specific_1982_2005 and www.aihw.gov.au/cancer/data/acim_books/index.cfm

What are Australian men told about prostate cancer in the media?

Prostate cancer has become a big health news story, being the third most reported cancer after breast cancer and melanoma [46]. Much of this reportage – although certainly not all – is accurate and important in raising awareness [47]. But overwhelmingly, it actively 45promotes screening. As we saw at the beginning of this book, even though nearly all expert bodies which have reviewed the evidence on the ability of screening to save lives have concluded that the risks outweigh the benefits and that the number of lives saved because of screening would be small, this is decidedly not the message that is being communicated to men in the media [48].

In a study one of us (SC) published in 2007 on the accuracy of media reports about prostate cancer in 388 Australian newspaper and 42 television items, one in ten statements reported to the public were found to be inaccurate [47]. Examples of these included:

Prostate cancer, which kills more men in this country than any other form of the disease

Prostate cancer is … the biggest cause of cancer death in males … treat men for their commonest lethal cancer [wrong! Lung cancer kills far more]

Prostate cancer is the second biggest killer of Australian men [wrong! Heart disease, lung cancer, stroke and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease kill more men].

As we finished writing this book in August 2010, the Prostate Cancer Foundation of Australia’s website [49] states, “Each year in Australia, close to 3,300 men die of prostate cancer – equal to the number of women who die from breast cancer annually.” In fact, there has never been a year in which “close to 3,300” men died of prostate cancer in Australia. The highest number that has ever occurred in one year was in 2005, when 2950 men died from the disease. In 2008, the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) published a projection for the number of prostate cancer deaths in Australia of 3366 in 2010 [50]. In the same report, it projected the figure of 3124 deaths from the disease in 2007. But in fact, as we saw in Table 1, 2938 men died from the disease in 2007 (the latest year for which 46data is available) – some 6% less than projected. The “3,330 each year” figure is therefore nearly 13% higher than the highest number ever recorded.

The Foundation’s chief executive, Andrew Giles, was reported in The Sydney Morning Herald in July 2010 as claiming that prostate cancer would soon become the No. 1 killer of Australian men:

By about 2015 the number of men this disease is killing is going to exceed the number of men who die of lung cancer, because that tumour is coming down thanks to all the work we do in tobacco control. So prostate cancer will be the number one killer of men. [51]

So how credible is this claim? In December 2008, AIHW estimated that in 2010 there would be 4687 deaths from lung cancer and 3366 deaths from prostate cancer [50]. In fact, in 2007 – the latest available year, there were 4715 lung cancer deaths and 2938 deaths from prostate cancer. Far from going down, lung cancer deaths averaged 4675 across the seven years (2001–07). In the three years between 2007 and 2010, the AIHW estimated that deaths from prostate cancer would grow by 428, or an average of 143 deaths a year. If this continued until 2015, this would mean that in the seven years (2007–2015), an extra 1000 deaths per year might occur, giving a rough total of 3939. If total lung cancer deaths continue to plateau as they have between 2006 and 2010, this would mean that Mr Giles’ prediction would fall some 746 deaths short – about a 25% overestimate.

In 2007, Professor John Shine, head of Sydney’s Garvan Institute, sent a fundraising letter to thousands of potential donors. It stated, “every single hour at least one man dies of prostate cancer”. Author (SC) wrote to the Garvan pointing out that this statement was massively incorrect. If prostate cancer killed one man an hour there 47would be 8760 deaths from the disease each year in Australia. With 2952 deaths in 2006, they overstated the true figure by 5808 – nearly 300% – explained later as an error arising from an extrapolation from UK data, unadjusted from that nation’s far greater population.

On 5 June 2007, Dr Andrew Rochford from Channel 7’s What’s Good for You stated that “prostate cancer is second only to heart disease” in killing Australian men. Prostate cancer is not “second only to heart disease” as a cause of death either. Prostate cancer was in fact the sixth leading cause of death in men, a very long way behind ischemic heart disease which kills 13,152 men a year; stroke (4826); lung cancer (4733); other heart disease (3290); and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (2986). Further, ischemic heart disease causes much more disability in the community than prostate cancer. Ischemic heart disease causes the loss of 151,107 DALYs (Disability Adjusted Life Years), compared with 36,546 lost to prostate cancer, putting it in ninth place by that criterion.

In August 2010, the Prostate Cancer Foundation issued press releases to publicise a conference it was hosting in Queensland. One report stated “the National Cancer Institute in the USA has in the last month reversed previous opposition to PSA tests and thrown out previous contrary studies”. We wrote to the NCI to ask whether this statement was accurate. They replied saying “Please note that as a Federal research agency, the NCI does not set screening guidelines”. They also referred us to the website of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) which they said

is the Federal agency responsible for setting screening guidelines. You may wish to explore the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) “Screening for Prostate Cancer: Recommendation Statement.”

48The USPSTF, which is sponsored by the AHRQ, is an independent panel of experts in primary care and prevention that rigorously evaluates clinical research in order to assess the merits of preventive measures, including screening tests. The link provided (www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsprca.htm) states unequivocally:

The USPSTF concludes that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of prostate cancer screening in men younger than age 75 years.

The USPSTF recommends against screening for prostate cancer in men age 75 years or older.

In other words, the idea that the NCI was ever “opposed” to prostate screening is misleading, as is the idea that the NCI has now “reversed” such opposition.

These examples are a small taste of some of the misinformation that is circulating about prostate cancer.