3

Home and away: the policy context in Australia

The policies that shape early childhood education and care (ECEC) in Australia are formulated within overlapping national and international contexts. Globalisation, the development of international law and the spread of electronic communication technologies all play a role in the rapid diffusion of ideas and practices to the broader policy community surrounding ECEC internationally. In recent decades ECEC has grown as a component of the in-kind service provision of all Western welfare states (Meyers & Gornick 2003). Women’s rising labour force participation and government policies mandating ‘workfare’ rather than ‘welfare’ are important reasons for this. So, too, are ideas about the significance of the early years for the intellectual, social and emotional development of children. According to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), ‘… the education and care of young children is shifting from the private to the public domain, with much attention to the complementary roles of family and early childhood education and care institutions in young children’s early development and learning’ (OECD 2000, p. 9). This chapter provides an overview of the domestic (‘home’) and international (‘away’) contexts surrounding Australian child care and early education policy. The broad argument is that there is a lack of fit between the emerging international agenda around ECEC which is increasingly child-focused and the Australian Government’s adult-centred, instrumentalist approach to ECEC which sees it as a service linked primarily to supporting workforce participation. The chapter begins with an overview of international developments and moves on to discuss the domestic policy framework established by the Coalition government since 1996.

International policy context

The international policy context of Australian ECEC has several elements: the treaties and conventions to which Australia is a 58signatory; the observation and monitoring of domestic policy by international organisations (sometimes, but not always, in the context of treaties and conventions) and policy developments in comparable countries. While none of these elements impose direct obligations upon Australia, all of them contribute to the broad context within which Australian policy is shaped and framed.

Australia has ratified two United Nations (UN) conventions that have potential relevance to child care: the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) and the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CROC)1. CEDAW provides an international framework for defining discrimination against women ando sets out an agenda for national action to end such discrimination. Among other things, CEDAW calls upon parties to provide supportive services, including childcare facilities, to enable parents to combine their family obligations with paid work and full participation in public life. The inclusion of child care within the CEDAW framework establishes it as ‘an affirmative obligation of government rather than simply another policy option’ (Davis 2005, p. 177). The Sex Discrimination Act 1984 gives partial effect to Australia’s obligations under CEDAW, but the focus of the Act is on direct discrimination against women in employment and the provision of services. The Act has not been interpreted as having any direct relevance to child care but there is potential for lobby groups to use the convention to push for an expansion of services. Regrettably, the Australian Government has not signed up to the part of CEDAW which calls on member states to provide paid maternity leave (Baird, Brennan & Cutcher 2002).

The Convention on the Rights of the Child is also relevant to Australian childcare policy. This convention requires parties to ‘render appropriate assistance to parents and legal guardians in the performance of their childrearing responsibilities’; it refers specifically to child care as one of these forms of assistance. Countries that have signed CROC are required to submit periodic reports to the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child. The

59Committee has no coercive powers; it can only ‘observe’ and ‘recommend’ (NCYLC 2002). Nevertheless, the ongoing requirement for the government to report to the International Committee on CROC means that there is at least some international oversight of Australia’s compliance with the provisions of the convention. This provides opportunities for local groups to bring pressure to bear on the government. Since ratification of CROC in 1990, Australia has submitted two reports (Australian Government 1995 and 2003) to the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child. Paralleling these official reports, non-government organisations have produced two ‘shadow’ reports providing alternative accounts of Australia’s compliance with CROC. The Australian Government’s record on child care has been one of the issues of contention in both reports. In their most recent report, the non-government organisations argue that, contrary to the Australian Government’s claim, access to good quality care is very limited in many areas, particularly for children under three years of age, and it is prohibitively expensive for low-income households (DCI and NCYLC 2005).

The effect of international treaties in Australia is limited unless specific legislation is enacted to give effect to their provisions; as we have seen, this has occurred (at least partially) in relation to CEDAW, but not CROC. The Non-Government Report on the Implementation of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child in Australia (2005) notes in relation to CROC that ‘The Australian Government has shown little interest in developing a domestic human rights regime to implement its … obligations under international law, and has little economic or political incentive to do so in the present circumstances’ (DCI & NCYLC 2005, p. xii).

In addition to its UN commitments, Australia has ratified two International Labor Organisation (ILO) Conventions that are relevant to the broad policy area of work and family: ILO Conventions 156 and 165. ILO Convention 156 (Workers with Family Responsibilities) promotes equality of opportunity for workers with responsibilities for family members. Countries that sign the Convention are required to take account of the needs of such workers in community planning and ‘to develop or promote community services, public or private, such as child care and family 60services and facilities’. ILO Convention 165 acts as a set of guidelines spelling out what parties should do in relation to the childcare and family services referred to in ILO 156 (Australian Government 2006). These responsibilities include ‘ensuring that services meet the needs and preferences of the community and ensuring that they comply with appropriate standards’ (ALRC 1994). The government claims that its responsibilities under ILO 156 are met, at least in part, through the Workplace Relations Act which ‘aims to help prevent and eliminate discrimination on a range of bases including family responsibilities’ (Australian Government 2006). While no child care initiatives have emerged directly from Australia’s ratification of ILO 156 it remains an important contextual element in Australian ECEC policy.

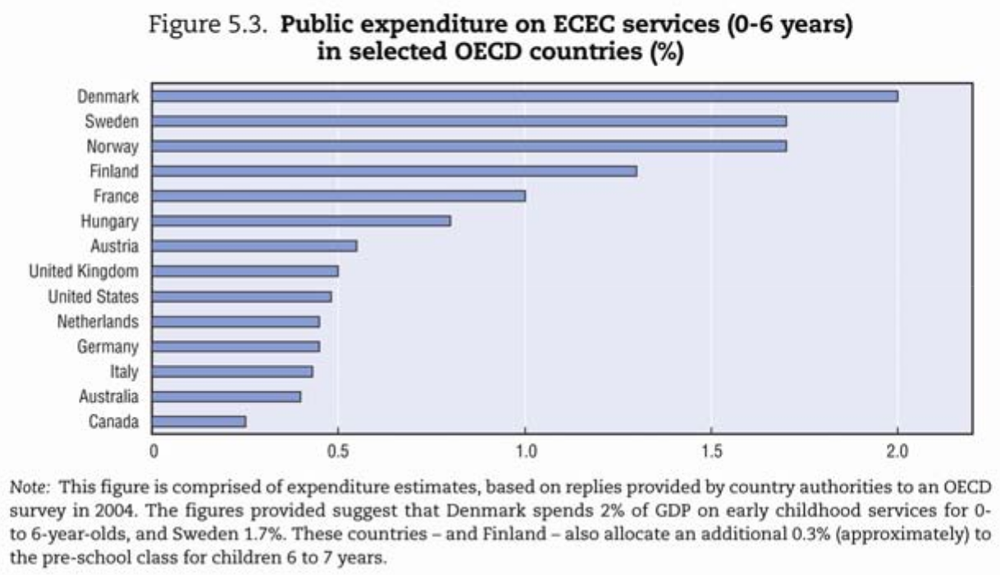

Australia is also linked into international benchmarking and comparison through membership of the OECD. In recent years, the OECD has taken a growing interest in social policy matters including work/family reconciliation and early childhood education and care. In a series of reports entitled Babies and Bosses, the social policy division of the OECD has analysed the ‘work/family reconciliation’ policies of eight countries including Australia (OECD 2001). In addition, the Education Directorate of the OECD has produced two major reviews of ECEC entitled Starting Strong (OECD 2000; OECD 2006). The 2006 report showed expenditure on early childhood education and care in Australia to be significantly lower than many comparable countries (Figure 3.1).

The other important element of the international context for early care and education is policy development in comparable countries. While this is not the place for a comprehensive review of international developments in ECEC, several trends are worth noting. Writing about recent developments in family policy in Europe, Mary Daly has identified ‘a move towards granting children autonomous rights’ in relation to ECEC. Several European countries including Finland, Germany and Sweden guarantee each child a place in child care (Daly 2004, p. 139). Such measures place children at the centre of policy making and establish a personal relationship between the child and the state. In practice, of course, such rights are exercised in an indirect fashion, because they are taken up by parents on behalf of children. Nevertheless, framing 61ECEC services as the right of the child, rather than the parent, represents a considerable step forward in terms of children’s rights. According to Daly, Europe is now witnessing the development of a ‘children’s social policy’ as a result of three trends: increasing recognition of children as agents, growing interest in the wellbeing of children in their own right, and concerns about social sustainability (Daly 2004, p. 139).

Figure 3.1 Public expenditure on ECEC services (0–6 years) in selected OECD countries (%)

Source: OECD 2006, Figure 5.3

Australian policy context

Although the international context is an important element framing national care and education policies, domestic policy remains overwhelmingly important in most countries. This is certainly the case in Australia which is not part of any supra-national organisation (such as the European Union) capable of issuing ‘hard’ directives with which member states are required to comply. So, how does the Australian Government see its role and how has it framed the child care issue? In the lead up to the 1996 election, Liberal leader John Howard assiduously promoted the idea that Labor had neglected the single-income family, and spoke of his determination to swing the balance back in favour of ‘choice’. The 62year before his election as Prime Minister, Howard released a document outlining the ‘values, directions and policy priorities’ of a Coalition government. In a section entitled ‘Greater Choice and Security for Families’ it stated: ‘A Coalition government will move immediately to reduce the economic pressures on families (especially those with dependent children), to increase the opportunities open to them and to give them more genuine choices about how they live’ (Howard 1995, p. 36). Specific priorities included giving families ‘greater freedom to choose whether one parent cares full-time for their children at home or whether both are in the paid workforce’ and ‘address[ing] Labor’s current discrimination against parents who choose to remain at home to care for their children’ (1995, p. 36). The theme of providing support to families, especially two-parent families with a mother at home, had been a longstanding theme in Howard’s public career and ‘choice’ has been central to the government’s construction of a range of policy issues, including family taxation, child care and maternity leave. The reality of ‘choice’ under the Howard government has been scrutinised by numerous analysts (Apps 2002, 2004; Cass & Brennan 2003; Gittins 2004; Hill 2006). In relation to tax and welfare policies there is broad agreement that, far from increasing choice, the government has put in place strong workforce disincentives for women in low and middle-income families who are outside the social security system. (The situation is quite different from those in receipt of income support payments through Centrelink. Parents in this situation are compelled to seek part-time work regardless of their personal preferences or ‘choices’.)

Interestingly, there is no similarly agreed interpretation of childcare policy. Despite the fears of activists and childcare supporters, expenditure on child care has grown significantly under the Howard government. In the last year of the Keating Labor government approximately $555 million was allocated to childcare services; in 2005, the figure was $1.8 billion (FaCS 2006) There has been a corresponding increase in the number of places in federally supported child care and a significant expansion in the number of children with access to formal care. In 2002, 44.5% of 0–4 year olds used some type of formal child care, compared with 36.6% in 1996. And the proportion of children attending long day care has more 63than doubled in this period, from 13.2% in 1996 to 22.7% in 2002 (ABS 2002). Many criticisms may be levelled at the government’s childcare policy, but failure to expand the long day care sector is not one of them. The critical issue is the nature of that expansion: the reliance upon private, for-profit providers, and the impact of this upon standards and quality within the sector.

The demise of community based child care and the rise of ‘for-profit’ care

From the late 1970s until the early 1990s, Australia developed a unique approach to long day care services. This approach, deeply influenced by the advocacy of feminist organisations and trade unions, involved direct government subsidies to non-profit care, and combined this with community management at the local level. From the early 1990s onwards, however, as governments increasingly adopted neo-liberal strategies to accommodate globalisation and concerns about ‘big government’, the federal government’s policy orientation moved away from the establishment of new services, and towards a demand-side approach – providing assistance to families to help with their child care fees. Women’s groups and community childcare organisations strongly opposed this policy direction, arguing that the profit motive in child care was incompatible with high quality service provision. In the lead-up to the 1996 election, the Liberal Party made specific commitments to address ‘Labor’s child care failure’. These included retaining the operational subsidy for non-profit, community based centres, establishing a national planning framework to guide the development of new services, and extending of the accreditation system to family day care, out of school hours care and occasional care. Just days before the election, David Kemp, the Shadow Minister for Employment, Training and Family Services, wrote to the Australian Early Childhood Association assuring them of the Coalition’s ‘continuing support for the community-based long day care sector’. To drive home the point, he elaborated, ‘we regard the operational subsidy as one of the key supports of that sector. The Coalition has no plans whatever to change the operational subsidy’ (Parliament of Australia SCAC 1996).64

Despite this commitment, the Coalition government abolished operational subsidies for community based long day care centres in its first budget – the same budget that ushered in the family tax initiative to bolster the incomes of stay-at-home mothers. The message from this early budget was that the ‘choice’ for parents who wished to access non-profit child care was not as important as the ‘choice’ to withdraw from the workforce. The budget also contained cuts to childcare assistance, imposition of a means test on the childcare cash rebate and withdrawal of funding for 5500 new centre-based places scheduled to be built over the next few years. These measures paved the way for a radical restructuring of the long day care component of the Australian child care system. The federal government gave strong encouragement to the private sector, allowing it to establish centres wherever it chose (regardless of any planning principles) and extending subsidies to users of the services.

The generous terms on which federal subsidies were extended to the private sector rapidly brought new players in to the market. ABC Learning became incorporated as a public company in 1997 and listed on the stock exchange in 2001, signalling a new phase in the Australian childcare industry. It was followed by Child Care Centres Australia, FutureOne and Peppercorn. Other companies, including Hutchinson’s Child Care Services and Childs Family Kindergartens, listed on the stock exchange in 2004 and 2005 respectively. Prospective investors were advised that ‘[t]here are few other businesses where as much as 75 per cent of gross income is payable monthly in advance to the operator’ (Loane 1997, p. 252).

The corporatisation of Australian child care has yielded immense profits for some individuals and companies. ABC Learning recorded a $38.07 million half-year profit in early 2006 – more than double the $14.27 million for the same period in the previous year. It forecast a full-year profit of $88 million on its Australian and New Zealand centres alone, with additional earnings to be derived from its acquisition of the Learning Care Group (LCG) in the USA. LCG is the third largest child-care company in the USA, with 460 centres in 25 US states (Ambler 2006). In 2006, average earnings per centre (before interest and tax) for ABC Learning were projected to be $180 000 (Fraser 2006). ABC shares have grown in value twenty-fold since the company floated in 2001, 65taking its capitalisation to $2.5 billion (Wisenthal 2006). The shift to the private sector has undoubtedly resulted in a rapid expansion of long day care places. However, there are indications of downward pressure on standards and quality. As community child care has declined as a percentage of all federal services, pressures to reduce licensing standards and to abandon the existing system of accreditation in favour of industry self-regulation have intensified. When state regulations have been under review, private childcare lobby groups have intervened. Challenges by corporate providers were made to the Queensland regulations concerning staffing during lunchtime and during breaks (Horin 2003). Corporate providers are, of course, legally obliged to maximise profits for their shareholders. If regulations governing staff qualifications, group sizes, adult/child ratios and basic health, nutrition and safety requirements are seen as barriers to profit, then at least from a business perspective it may be quite appropriate to try to reduce such ‘costs’ (Teghtsoonian 1993).

Inadequacies of regulation and quality standards

There are a number of concerns about the role played by major corporations in child care; the major one is the relationship between profit-making and service quality. Private profit-making is not acceptable and is not permitted in the school education sector (indeed, when one major corporation tried to move into the area of school education, the Queensland Government moved quickly to forestall such a move.)

Recent research conducted by the Australia Institute (Rush 2006) suggests that, based on reports by staff, the poorest quality care is being provided in child care centres that are part of corporate chains. Independent private centres offer a level of care that is similar to community based, non-profit centres. On the critical issue of staff members’ own perceptions of their ability to form relationships with children, community-based and independent centres performed significantly better than the corporate chains, with about half the staff from the former two types of care agreeing that they always have time to develop individual relationships, compared to only a quarter at corporate centres (see also Chapter 8).66

There is evidence from the survey that corporate centres are cutting costs in order to improve profits. Less than half the staff in corporate care felt that children are supplied with adequate, nutritious food, compared with around three-quarters in the other two types of care. Forty per cent of community-based, non profit services operate with more than the minimum number of legally required staff, compared with fourteen per cent of the corporate chain centres (Rush 2006, p. 8).

Planning issues and gaps in service provision

One of the major issues in the provision of early childhood services is the lack of detailed, consultative planning. Macro level data are available from the Australian Bureau of Statistics, but local level planning is noticeably absent. Rudimentary data are available in respect of outside school hours care, family day care and in-home care, since existing services are asked to record the number of places requested. The Department of Family and Community Services and Indigenous Affairs does not measure unmet demand for long day care. Thus, the one service type in respect of which no planning occurs is long day care – the service which accounts for the largest share of the child care budget and the biggest number of child care places. In respect of long day care, the market literally rules. Private providers can establish services wherever they wish and, so long as those services become part of the Quality Improvement and Accreditation System, users of these services will be eligible for Child Care Benefit (CCB).

As might be expected from the substantial growth in services discussed above, there is evidence that demand for additional services is slowing down. ABS Child Care surveys conducted in 1993, 1996, 1999 and 2002 showed a steady decline in the number of children requiring additional (or some) formal care. In 1993, formal care was required for 279 000 children aged 0–4; in 2002, the corresponding number was 106 400. A similar drop was recorded for children aged 5–11 years. More than 210 000 children in this age group required formal care in 1993, compared with 68 000 in 2002 (ABS 2002, p.18). However, closer scrutiny of these figures shows that the pressure remains on particular forms of care and that the availability of services varies according to geographical location and the age of the child. The main pressure points and 67areas of under-provision continue to be the outer suburbs of large cities, rural and regional areas and services for children below the age of three (NACBCS 2004).

The cost of child care

One of the most politically sensitive issues in the current child care debate is the cost of care to parents. The Australian Government provides Child Care Benefit (CCB) to reduce the costs that parents face in using approved care.2 Up to 50 hours of CCB is payable if parent(s) meet a work test, and 24 hours CCB is available to other families. The amount of CCB depends upon various factors including family income, the ages of children in care and the number of hours of care required. At the extreme, a family with an income below $34 300 (including those on income support) may be eligible for up to $168.50 per week. The CCB tapers down to about $25 per week for the 10 per cent or so of families with combined incomes over $108 000. Thus, $168.50 is the maximum CCB available to a low-income family and $25 is the maximum for a high income family. However, these levels of subsidy are payable only in respect of children below school age who attend the service for 50 hours per week. In 2005, the median number of hours spent in formal care was 10 (down from 11 in 2002) and less than three per cent of children were in long day care for 50 or more hours per week. The proportion of children from low-income families who attend child care for 50 hours and thus attract the maximum subsidy is likely to be miniscule – particularly since families must pay the difference between CCB and the actual fee charged by the service.

Child Care Benefit is structured to give the highest dollar value to low income families, but families are required to meet the

68difference between CCB and the actual fee charged by the service, which, in some instances, can be considerable. Childcare fees vary from state to state and between private, for-profit care and community based care (see Table 3.1) but the average fee in private long day care in 2004 was $208, leaving a gap of $82 per week, on average, for families using full-time child care. Again, however, it must be emphasised that very few families are in fact using full time care. Fees and costs are not the same.

Table 3.1 Long day care centres, average weekly fees, 2004

| STATE | Private | Community-based | Family day care |

| $ | $ | $ | |

| NSW | 222 | 228 | 195 |

| VIC | 204 | 209 | 180 |

| QLD | 195 | 186 | 172 |

| SA | 199 | 197 | 186 |

| WA | 196 | 194 | 192 |

| TAS | 209 | 195 | 200 |

| NT | 188 | 180 | 181 |

| ACT | 229 | 225 | 217 |

| Australia | 208 | 211 | 185 |

Source: FaCS 2005, Tables 4.1.3, 5.1.3, 6.1.1

During the 2004 election campaign, the government announced an additional measure, the Child Care Tax Rebate (CCTR) to assist working parents with their child care costs. CCTR was presented as a 30 per cent rebate on out-of-pocket child care costs (that is, child care costs minus Child care Tax Benefit). After the election, the Treasurer announced that a cap of $4000 would be applied and that the CCTR would not be claimable until 2006. In other words, parents would have to wait for up to two years to claim this benefit. The administrative and record-keeping requirements of the CCTR are complex. The CCTR is based on completely different principles to CCB: it is designed to provide the highest benefits to those with high childcare costs – and, since high child care costs are strongly 69correlated with high incomes, it is clear which families will benefit the most (see Table 3.2). Further, the CCTR is only available to offset tax, so low-income families will miss out if the amount for which they are eligible is greater than their tax bill. Partnered women can transfer any unused portion of the rebate to their partners; single mothers have no such option. The CCTR has been criticised from many quarters; it seems plain that it is not intended to address the problem of childcare affordability for those most in need, rather it is a response to intense lobbying from those who represent families in the highest income bracket.

Table 3.2: Combined impact of CCB and CCTR at differing family income levels

| Family adjusted taxable income 0 $ | CCB received (per week) $ | Out of pocket amount $ | CCTR Received (per week equivalent) $ | Combined CCB and CCTR received (per week equivalent) $ | % of child care costs covered by CCB and CCTR |

| 30 000 | 144.00 | 56.00 | 16.80 | 160.80 | 80.4 |

| 50 000 | 112.00 | 88.00 | 26.40 | 138.40 | 69.2 |

| 70 000 | 73.54 | 126.46 | 37.94 | 111.48 | 55.7 |

| 100 000 | 24.15 | 175.85 | 52.76 | 76.91 | 38.5 |

Source: Parliamentary Library

Note that these are notional, rather than actual, benefits. Families <$30,000 who would receive $144 in CCB, only receive this if they had a child in care for 50 hours per week (only 6 per cent of children meet this criterion) and the family was able to meet the difference between CCB and the actual fee charged by the service. The average CCB paid per child in 2003–2004 across all income groups was $1,401 or $28 per week.

Conclusion

Australian childcare policy operates within a complex web of domestic and international policy contexts. At the international level, Australia has signed up to a number of treaties and conventions which encourage substantial attention to ECEC. An 70emerging trend in European childcare policy is to see the child (rather than the parent) as the focus of policy. Although Australian policy makers are well-attuned to such international initiatives, they have made little impact on the direction of policy in this country. Despite record expenditure and the highest ever number of children in federally supported services, the sector lacks vision and direction; there are major concerns about quality and affordability and widespread anxiety about the hundreds of millions of dollars now being directed to corporate childcare chains. Australia’s reputation as a nation with a system of high quality, non-profit care has been squandered.

71

References

Australian Bureau of Statistics 2002, ABS Child Care Survey 2002, cat. no. 4402.0, ABS, Canberra.

Australian Government 1995, Convention on the rights of the child, report CRC/C/8/Add.31.

Australian Government 2003, Convention on the Rights of the Child: Second and Third Periodic Reports due in 1998 and 2003, CRC/C/129/Add.4, viewed 3 October 2006, www.ohchr.org/english/bodies/crc/crcs40.htm.

Australian Government 2006, Work and Family, Legislation and Policy, viewed 3 October 2006, www.workplace.gov.au/workplace/Category/SchemesInitiatives/WorkFamily.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2005, Australia’s Welfare, AIHW, Canberra.

Australia Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2003, Australia’s Welfare 2003, cat. no. AUS 41 531.

Australian Law Reform Commission (ALRC) 1994, Child Care for Kids: review of legislation administered by Department of Human Services and Health, ALRC, Sydney.

Ambler, E 2006 ‘ABC Chalks up Interim Result’, Sydney Morning Herald, 28 February.

Apps, PF 2002, ‘Howard’s family tax policies and the First Child Tax Refund’ in The Drawing Board, viewed 3 October 2006, www.australianreview.net/digest/2001/11/apps.html.

Apps, PF 2004, ‘The high taxation of working families’, Australian Review of Public Affairs, vol. 5, pp. 1–24.72

Baird, M, Brennan, D & Cutcher, L 2002, ‘A Pregnant Pause in the Provision of Paid Maternity Leave in Australia’, Labour and Industry, vol. 12, no. 4.

Cass, B & Brennan, D 2003, ‘‘Taxing Women: The politics of gender in the tax/transfer system’, eJournal of Tax Research, vol. 1, no. 1, August, pp. 37–63.

Daly, M 2004, ‘Changing Conceptions of Family and Gender Relations in European Welfare States and the Third Way’, in J Lewis and R Surender (eds), Welfare state change: towards a third way?, Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp. 135–56.

Davis, Martha F 2005, ‘Child care as a human right: A new perspective on an old debate’, Journal of Women, Politics and Policy, vol. 27, Nos. 1/2, pp. 173–9.

DCI and NCYLC (Defence for Children International and National Children’s and Youth Legal Centre) 2005, The Non-Government Report on the Implementation of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child in Australia, http://www.dci-au.org.

Family and Community Services (FaCS) 2006, Unpublished data provided to the author.

Ferguson, A 2003, ‘The Industries Set for Success’, Business Review Weekly, 25 July, p.50.

Fraser, A 2006, ‘ABC marks up centres in campus bid’, The Australian, March 16.

Gittins, R 2004, ‘Female economists have home truths for Howard’, Sydney Morning Herald, May 22.

Hill, E 2006, ‘Howard’s Choice: The ideology and politics of work and family policy 1996–2006’, Australian Review of Public Affairs, Digest, viewed 17 April 2007, www.australianreview.net/digest/2006/02/hill.html.73

Horin, A 2003, ‘When Making Money is Child’s Play’, Sydney Morning Herald, October 4.

Howard, J 1995, The Australia I Believe In: The values, directions and policy priorities of a coalition government, Liberal Party of Australia, Canberra.

Lewis, J & Giullari, S 2005, ‘The Adult Worker Model Family, Gender Equality and Care: The Search for New Policy Principles and the Possibilities and Problems of a Capabilities Approach’, Economy and Society, vol. 34, no. 1, 76–104.

Loane, S 1996, Who Cares? Reed Books, Kew, Victoria.

Meyers, M & Gornick, J 2003, ‘Public or Private Responsibility? Early Childhood Education and Care, Inequality and the Welfare State’, Journal of Comparative Family Studies, vol. 34, no. 3, Summer, pp. 379–411.

Murray, S 1997, ‘Minimum Australian Child Care Standards: A Comparison with International Benchmarks’, Australian Journal of Social Issues, vol. 32, no. 2, 149–58.

National Association of Community-Based Children’s Centre (NACBCS) 2004, Children: Too Precious for Profit, viewed 17 April 2007, www.ccinc.org.au/childrenfirst/political_policy.htm.

National Children’s and Youth Law Centre (NCYLC) 2002, What’s Up CROC?Australia’s Implementaion of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CROC), viewed 3 October 2006, www.ncylc.org.au/croc/allaboutcroc2.html.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 2000, Starting strong – early childhood education and care, OECD, Paris.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 2001, Babies and bosses: reconciling work and family life, vol. 1, Australia, Denmark and the Netherlands, OECD, Paris.74

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 2006, Starting strong II – early childhood education and care, OECD, Paris.

Parliament of Australia Senate Community Affairs Committee (SCAC) 1996, Child Care Legislation Amendment Bill Report, viewed 17 April 2007, www.aph.gov.au/Senate/committee/clac_ctte/completed_inquiries/1996-99/childcare/report/index.htm.

Rush, E 2006, Child care quality in Australia, discussion paper no. 84, The Australia Institute, Canberra.

Teghtsoonian, K 1993, ‘Neo-conservative Ideology and Opposition to Federal Regulation of Child Care Services in the United States and Canada’, Canadian Journal of Political Science, no. 26, pp. 97–121.

Walsh, K 2006, ‘Kelly’s plea to PM: fix child care shambles’, Sun-Herald, January 15.

Wisenthal, S 2006, ‘ABC Learning Centres grow like topsy’, Australian Financial Review, March 13.

1 The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights is also, arguably, relevant to child care as a human right (see Davis 2005) but its provisions are beyond the scope of this discussion.

2 ‘Approved care’ refers to services approved by the Australian Government to receive CCB on behalf of families. Such services can include long day care, family day care, in homecare, outside school hours care and occasional care services. Families can also claim the minimum rate of CCB if their child attends ‘registered care’. This can be care provided by grandparents, relatives and friends – so long as they have registered with the Family Assistance Office.