CHAPTER 6

ARTEFACTS FROM CHEYNE BEACH

When the analysis of the Cheyne Beach artefacts was done in the late 1980s/early 1990s there had been almost no historical archaeological research carried out in Western Australia and no regional comparative assemblages or analyses were available. Similarly, much of what was then available from elsewhere in Australasia at the time was descriptive rather than quantitative analysis and of that most was unpublished or locked in inaccessible grey literature reports. There was little or no uniformity in the structure or presentation of data, nor a clear means of drawing these sometimes idiosyncratic results into a comparative framework.

Consequently, the artefact analysis and presentation of data for Cheyne Beach was a very deliberate exploration of how a comparative framework might be established. In the absence of a clear model for dealing with historical period assemblages, the approach was based on the author’s previous experience with pre–historic assemblages. Jim Allen’s 1969 analysis of the Port Essington assemblage faced similar issues and evolved a similar response (Allen 2008), but a copy of his work was unavailable until late in the Cheyne Beach analysis process.

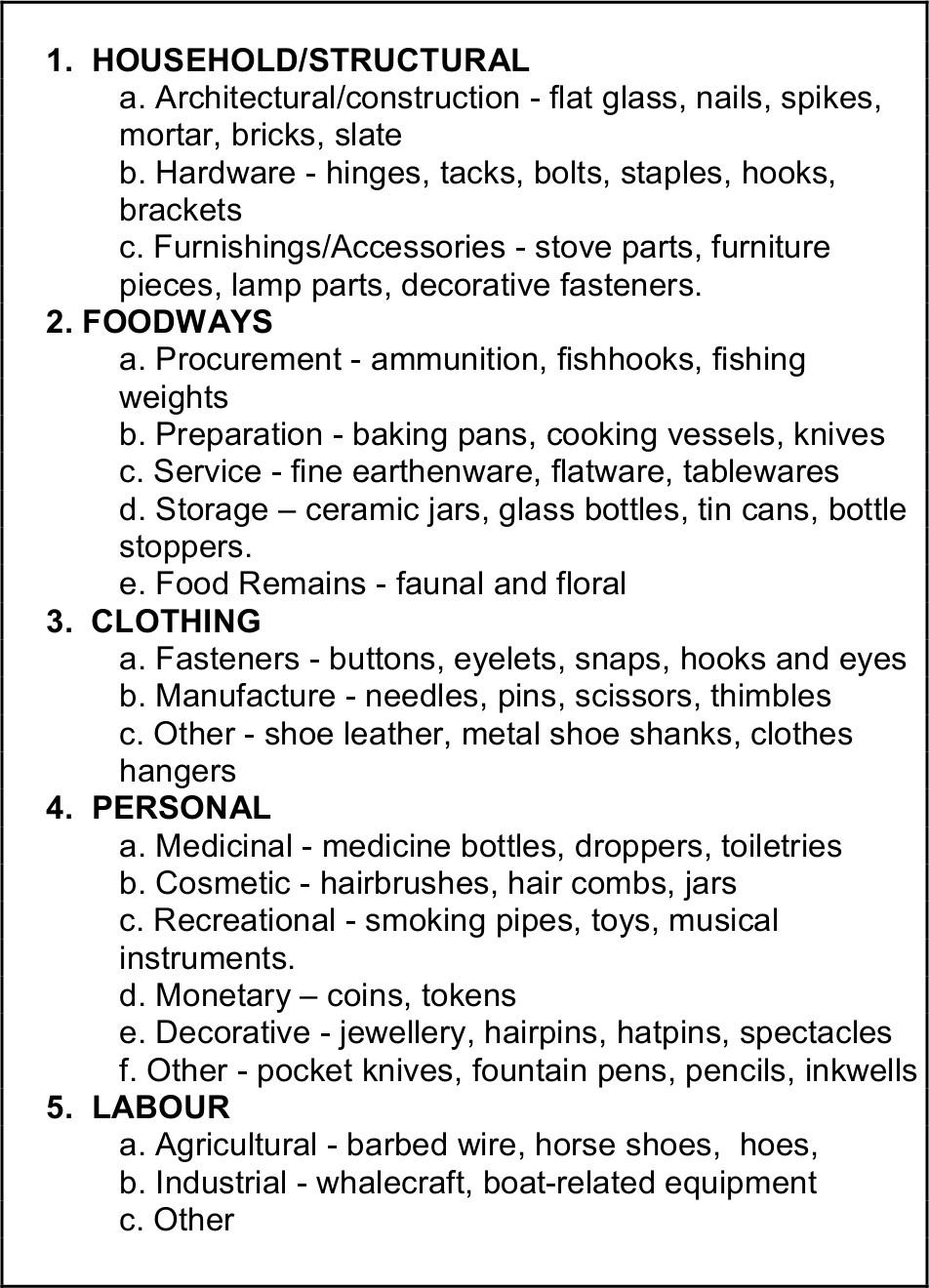

Table 6.1 Functional Categories (after Orser 1988:233).

The primary analysis of the Cheyne Beach artefacts was on the basis of functional classes, broadly following Orser’s categories (Orser 1988:233; see Table 6.1). Diagnostic artefacts were also identified for further analysis, while intrusive modern material was removed at this point. The following discussion is based upon the functional categories applied.

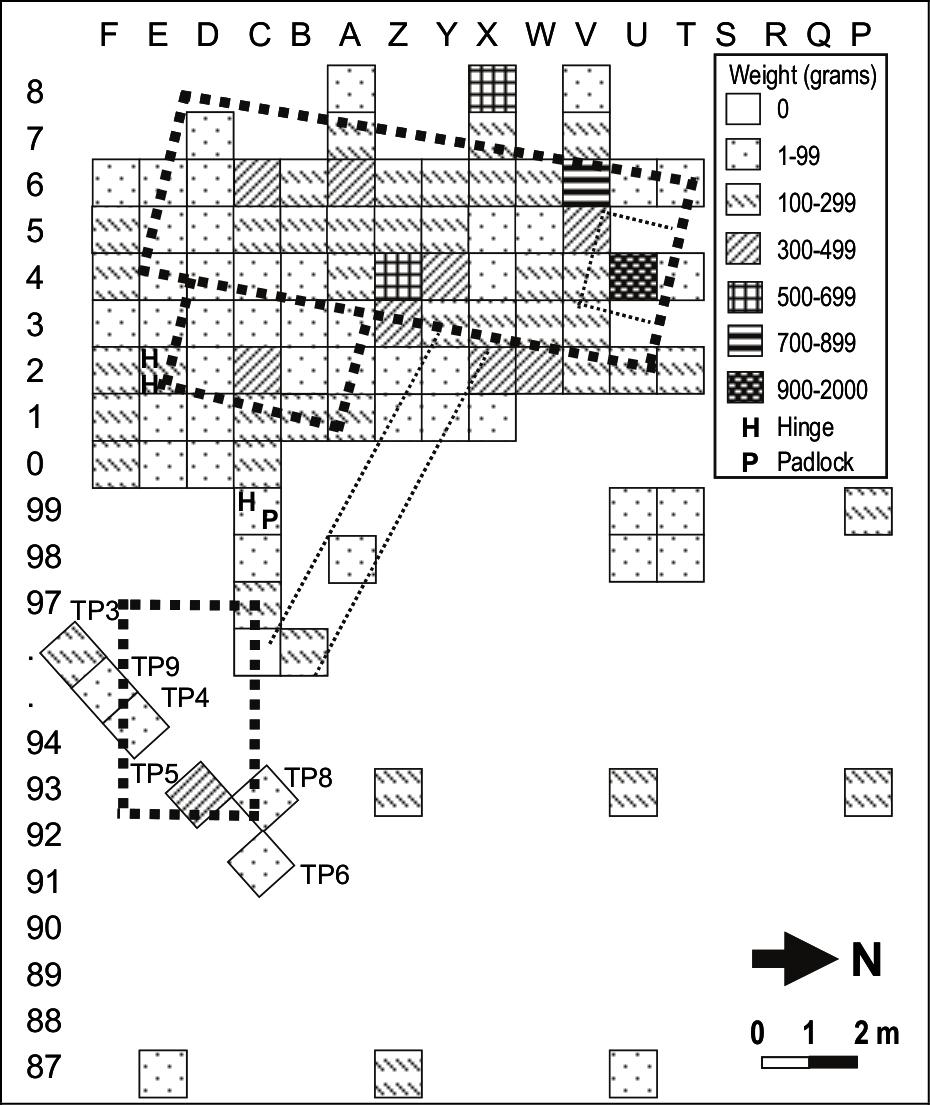

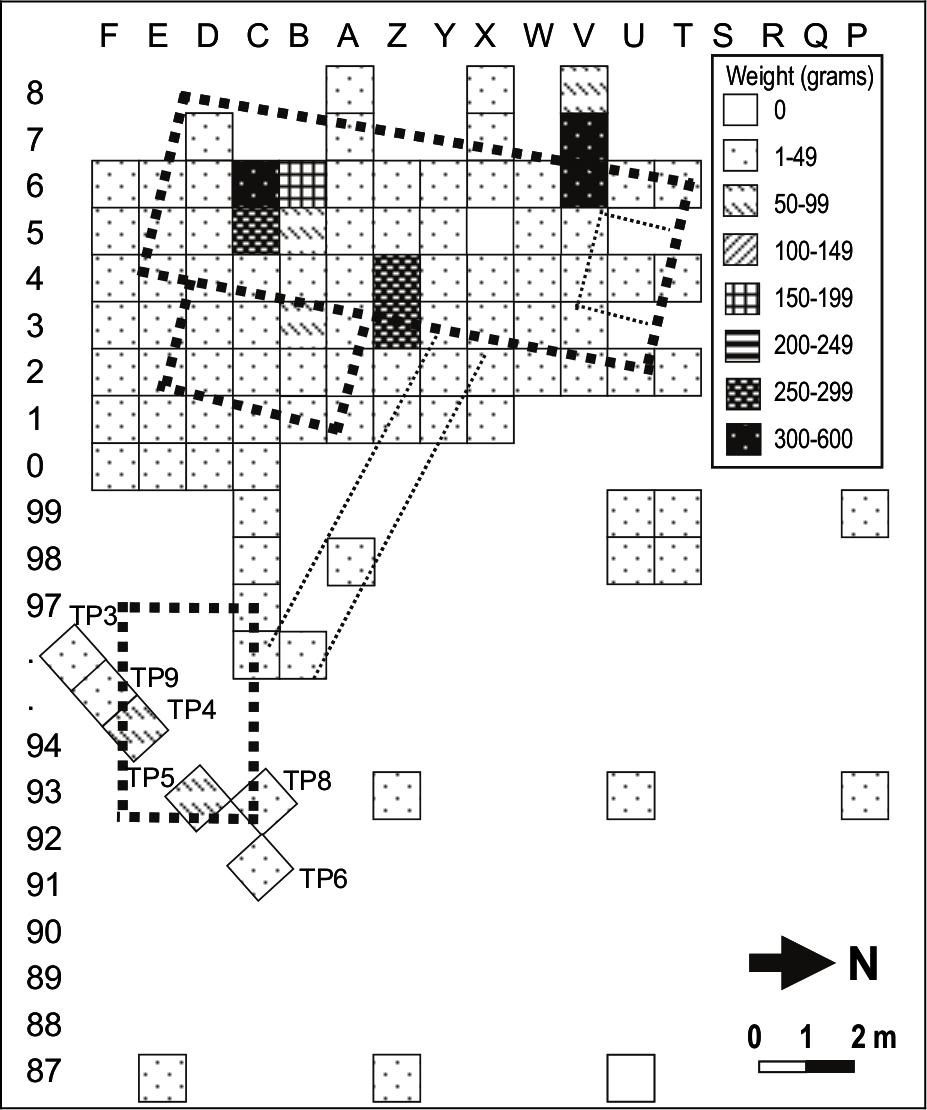

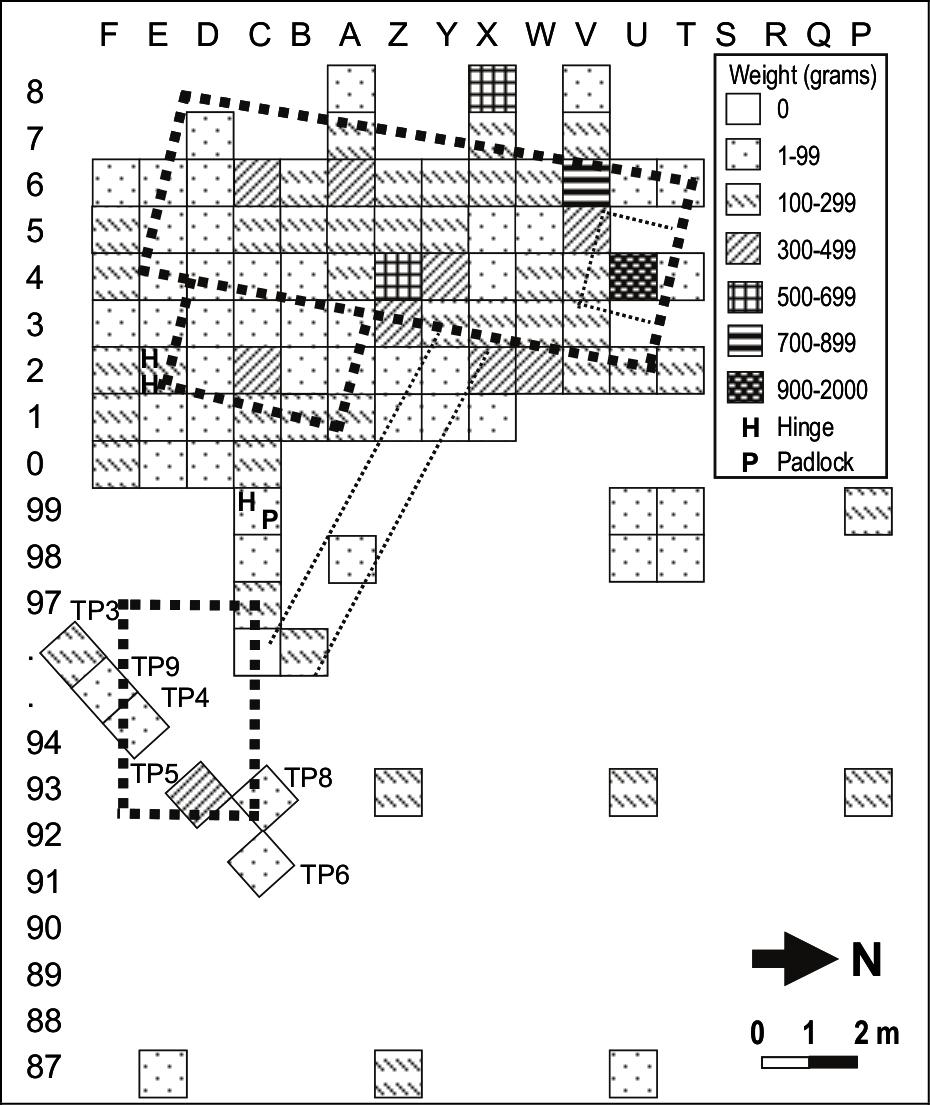

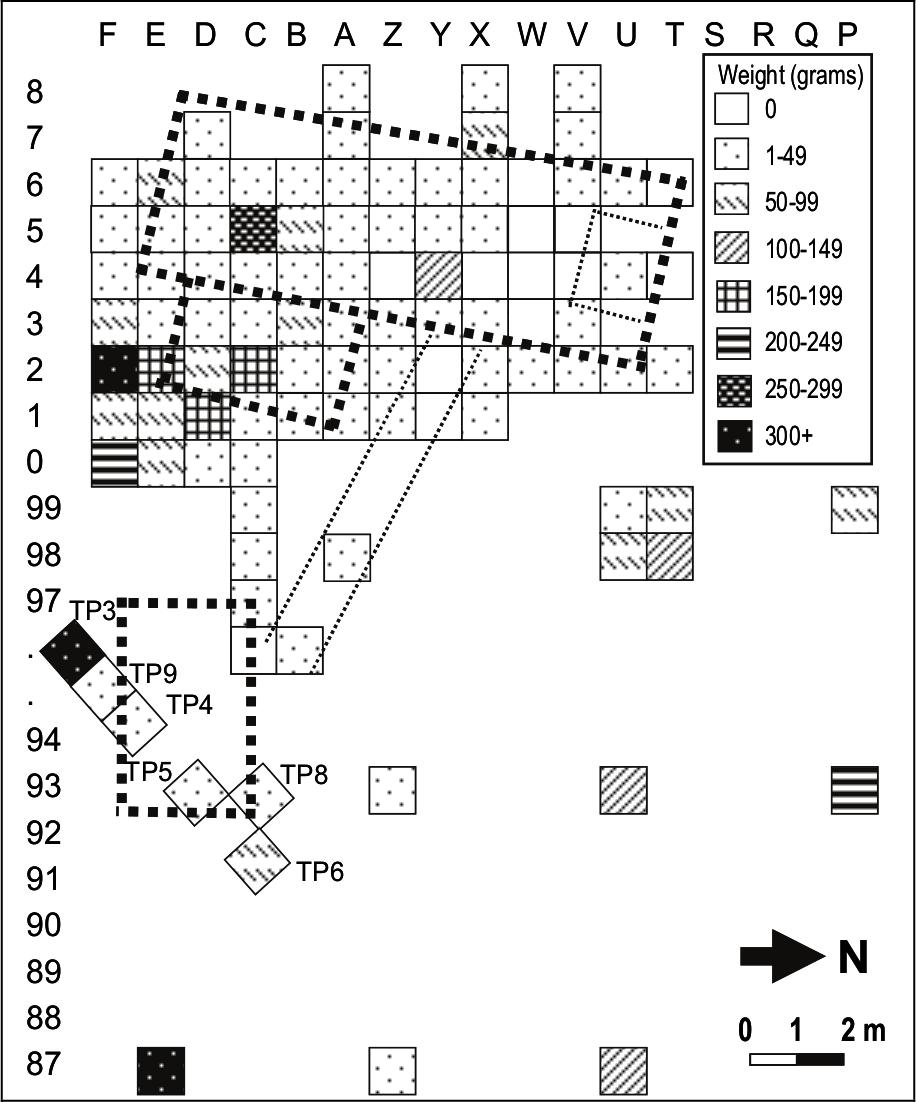

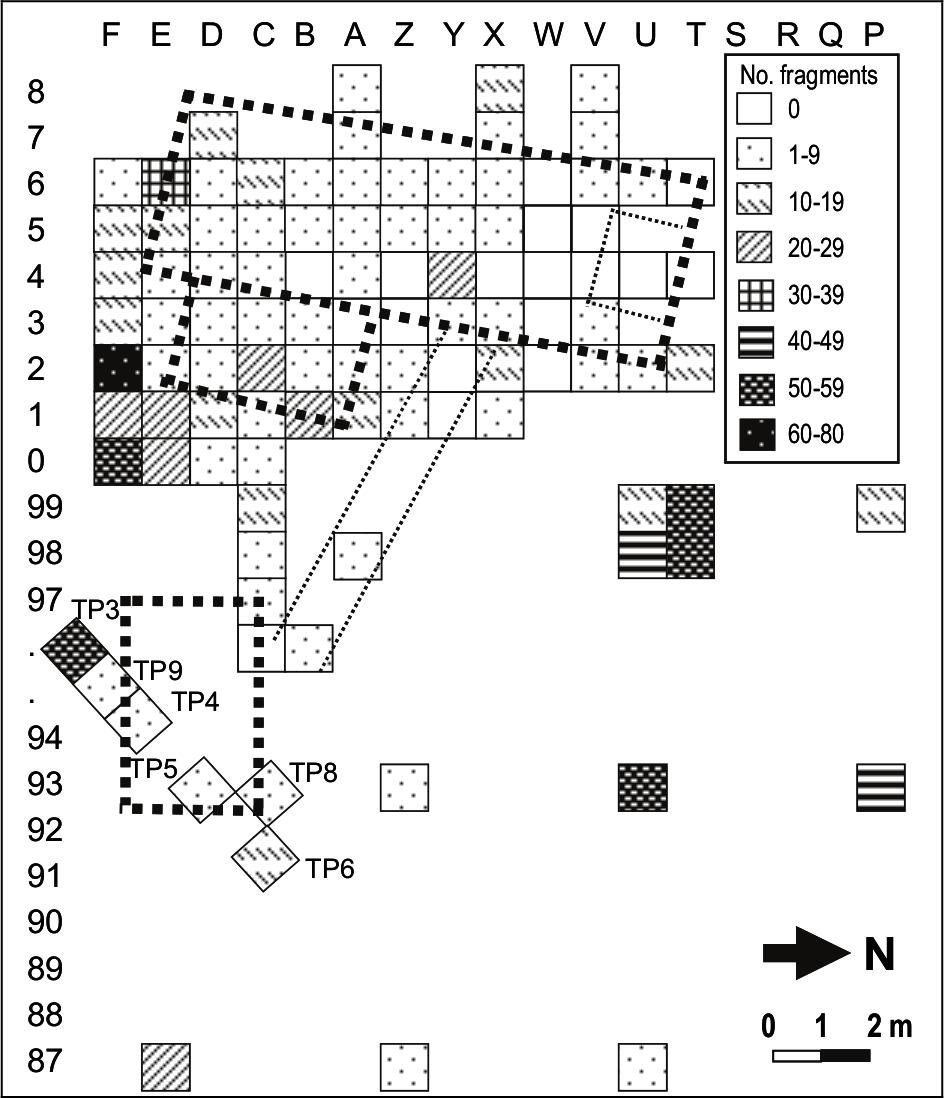

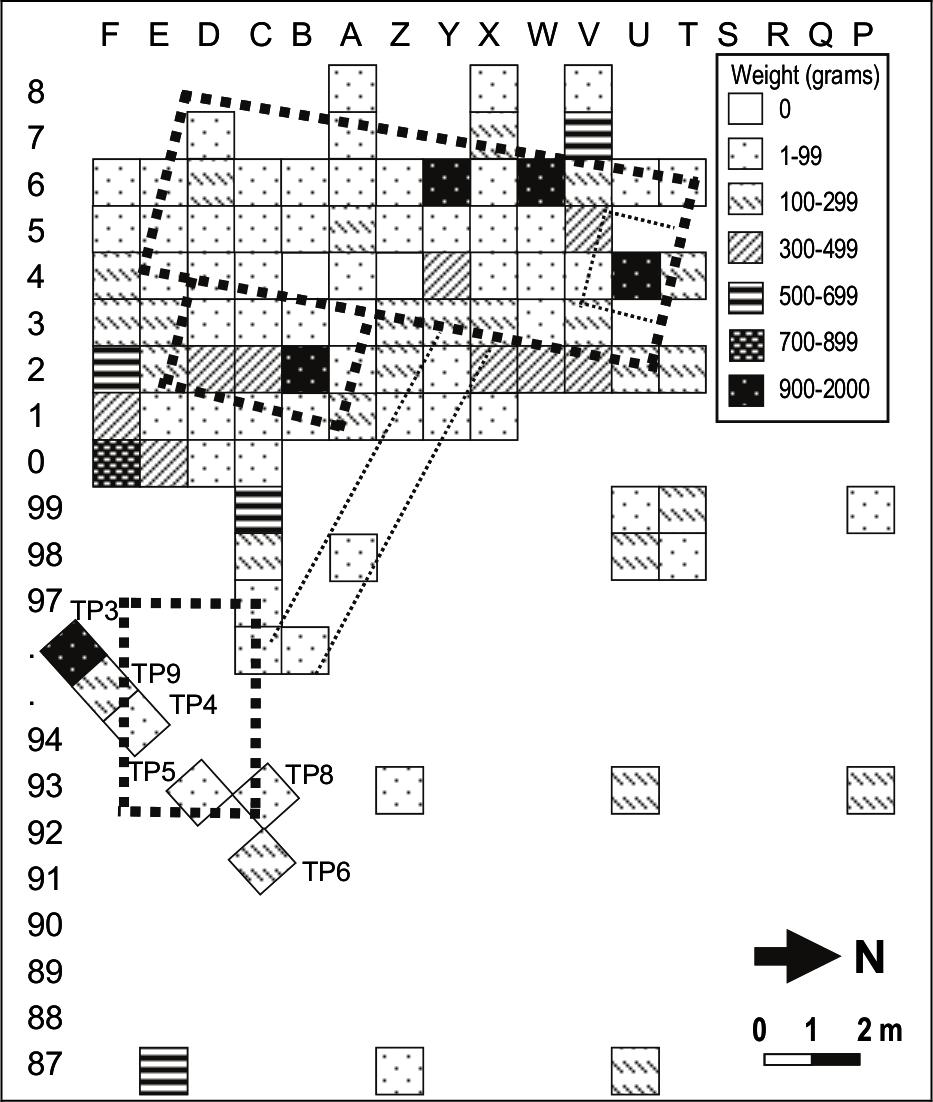

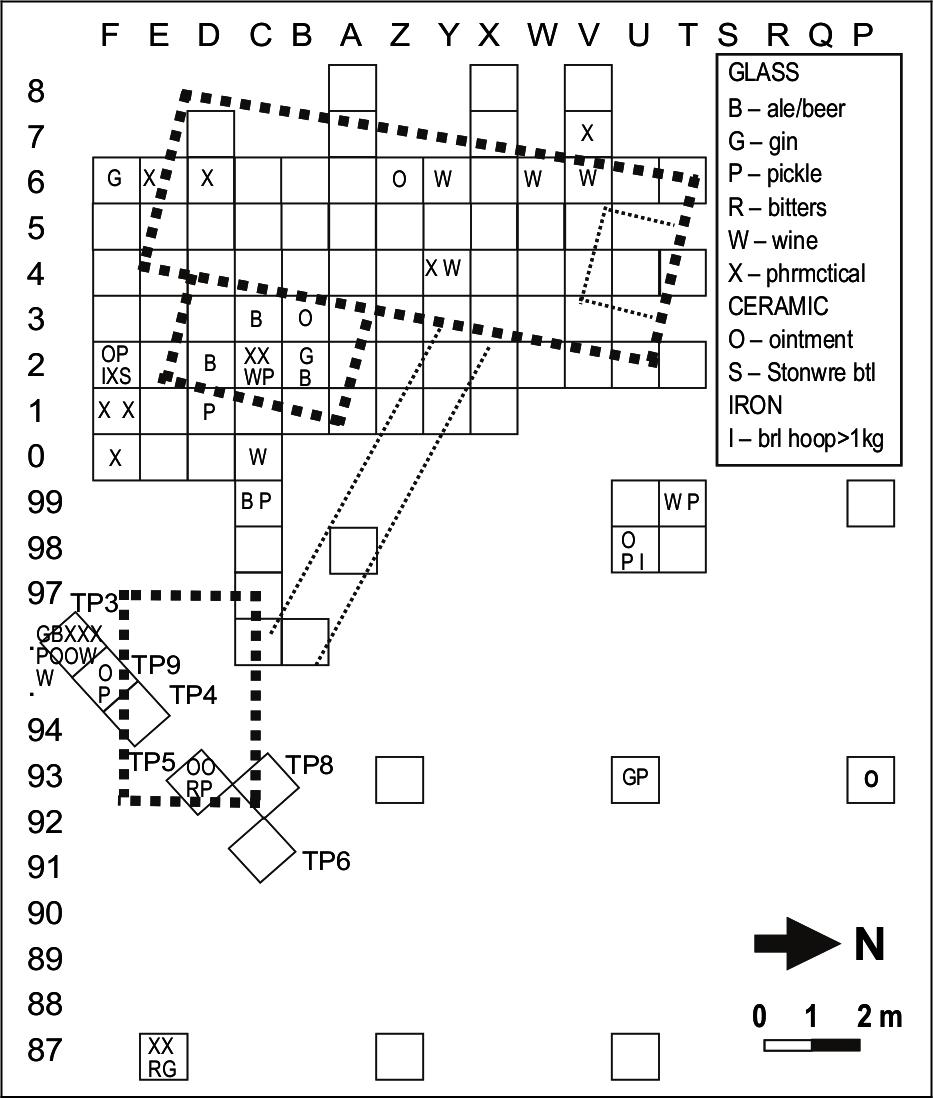

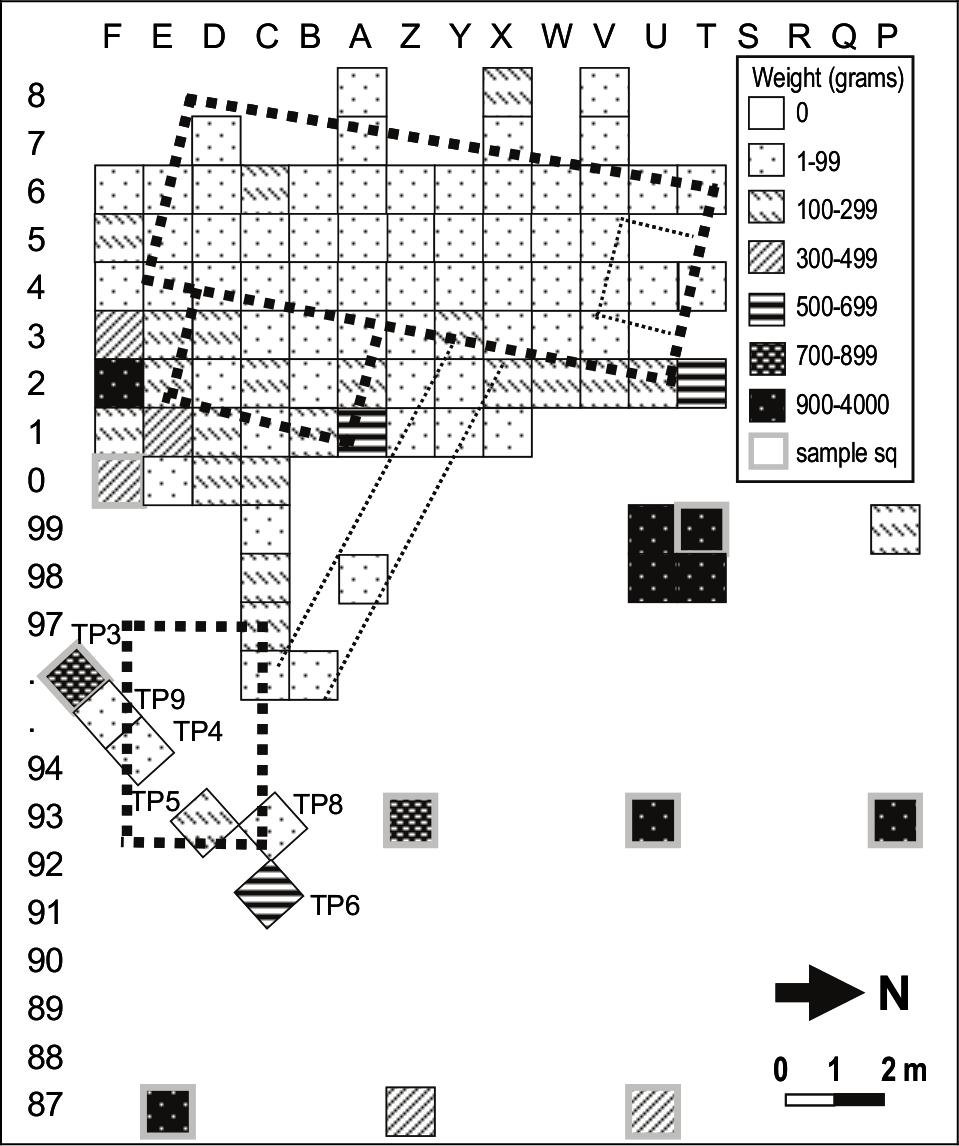

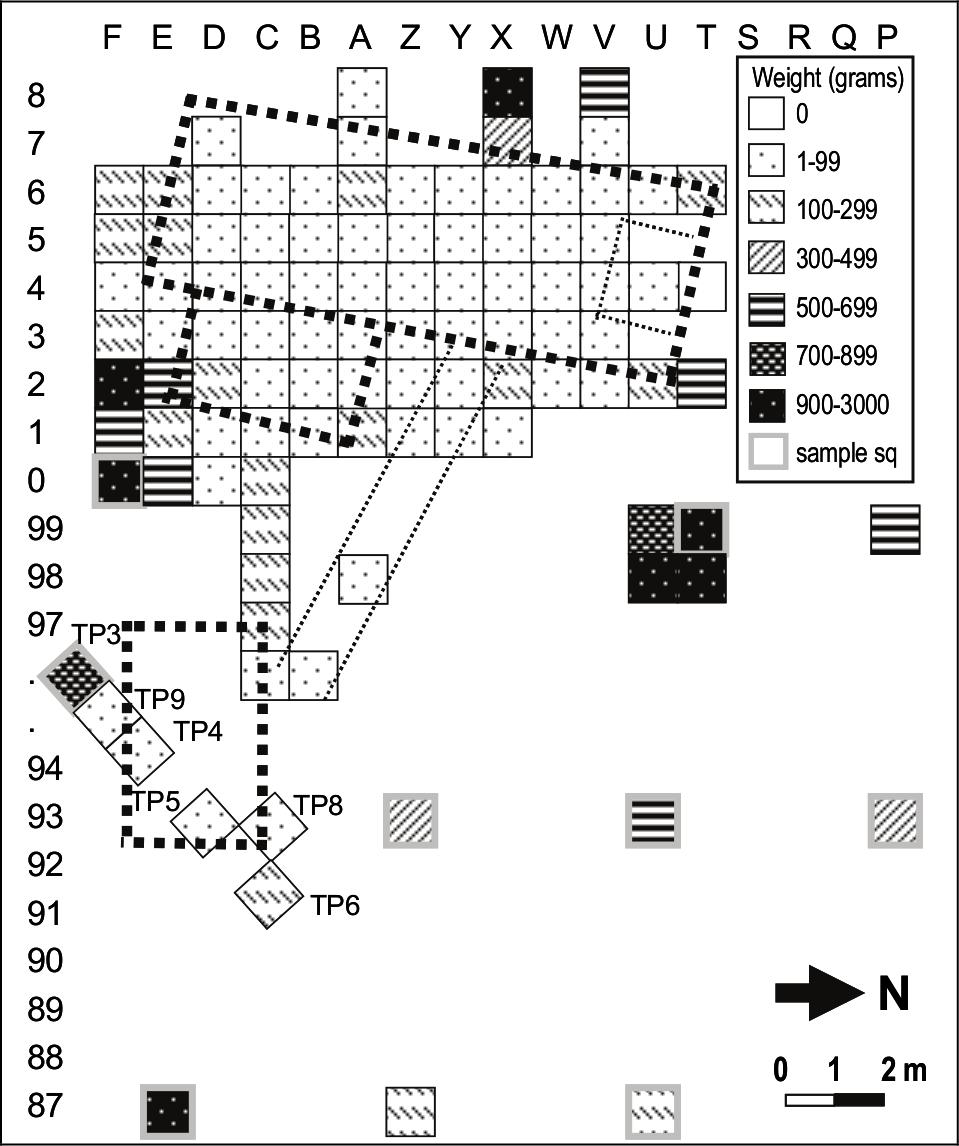

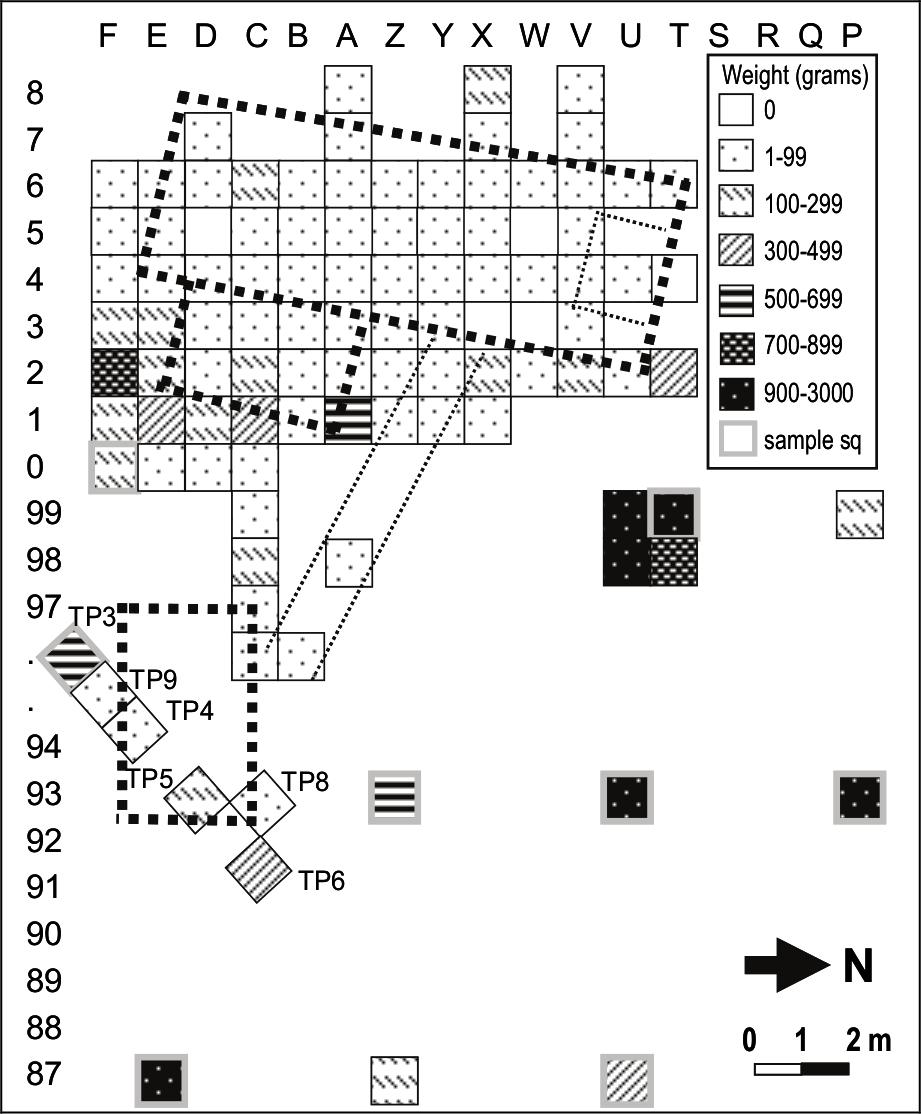

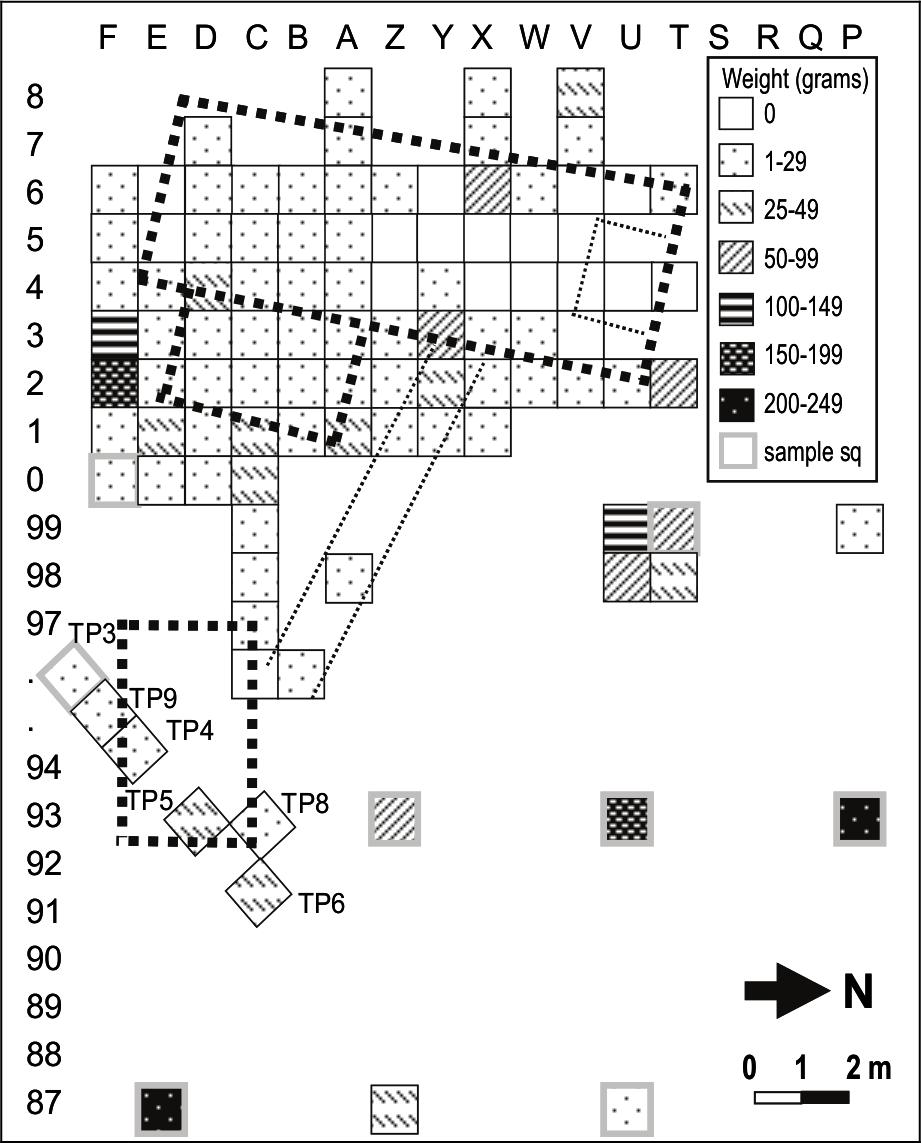

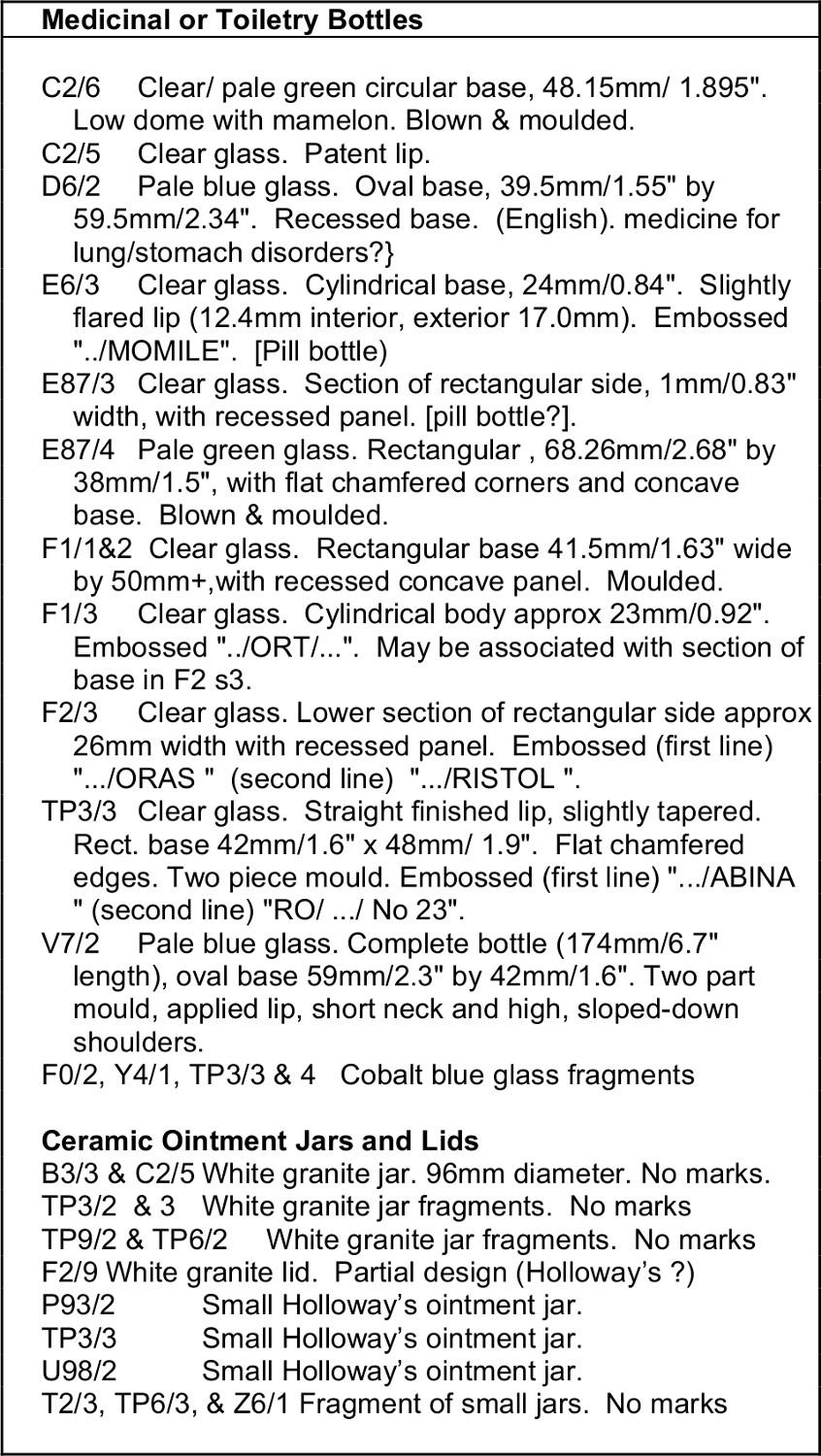

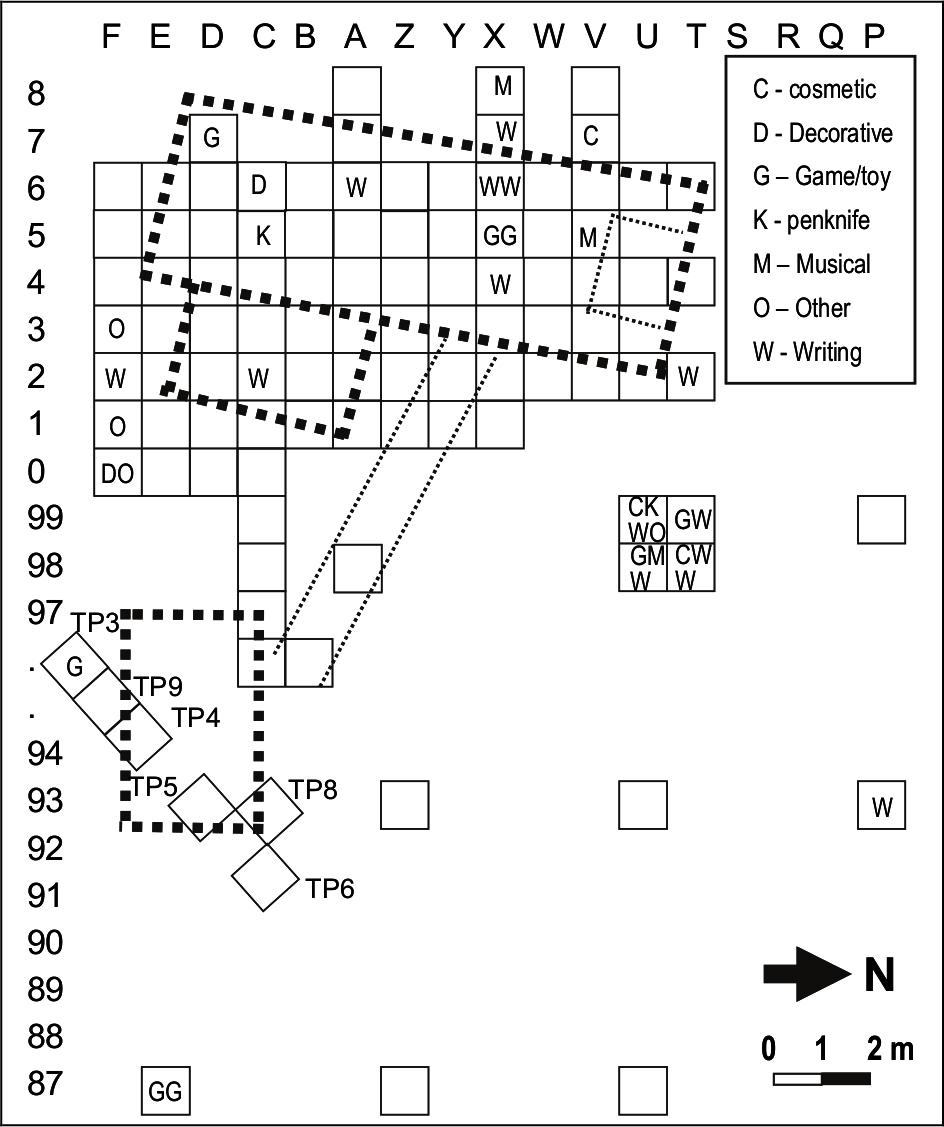

Another concern of the original study was the spatial distribution of artefacts. Although not necessarily advocating the sort of ‘pattern recognition’ proposed by South (1977), the potential for a nuanced examination of activity areas and discard behaviours seems reasonable. In this respect a deliberate effort was made to explore the distributions of different functional classes of artefact, using a variety of measures (number of elements, weight, etc). The total weight of artefacts in each square (excluding building materials), is shown in Figure 6.1. Larger structural materials (bricks, stone, whalebone) have been excluded.

Figure 6.1 Total Artefact Distributions.

HOUSEHOLD/STRUCTURAL

Architectural/Construction related artefacts

Bricks

Only four brick fragments were sufficiently complete to take measurements of their ends, but not of their lengths. Munsell colours were also recorded (Table 6.2). Even 79allowing for the irregularity of the surfaces measured, there is wide variation in width and thickness. These measurements show a squarer end than for the 19th century standard sizes in either the UK (4.5" x 2.5") or the USA (4" x 2.25") (Pearson 1988; Gurke 1987). All of the bricks are hand–molded, with varying textures. The third fragment is the largest found, having a length of 12 cm, and showing part of a frog. All of the samples are low–fired, with deteriorated or uneven sides, making it difficult to be confident that these measurements reflect the original sizes. Smaller fragments found in the floor layer provided a similar range of colours to those noted above, including a deeper red (2.5YR 5/6), although much of the variation is probably the product of their position within the kiln or clamp when the bricks were fired.

| width | thickness | code | colour |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. 7.9cm/3.1" | 6.9cm/2.7" | 5YR 7/4 | pink |

| 2. 8.6cm/3.3" | 6.8cm/2.7" | 5YR 7/2 | pinkish grey |

| 3. 8.2cm/3.35" | 7.2cm/2.8" | 10YR 7/4 | very pale brown |

| 4. 8.3cm/3.25" | 7.9cm/3.1" | 5YR 6/6 | reddish yellow, |

| to | 10YR 8/3 | very pale brown |

Table 6.2 Brick end measurements and Munsell colours.

Although there is clay in the general vicinity of Cheyne Beach, it is probable that the bricks were transported from Albany where brick kilns had been in operation since the mid 1830s (see Gardos 2004: 63, 258). A small quantity of a very light clay/lime mortar was recovered from around the hearth, but little from elsewhere which might indicate mortared stone or brick walls.

Nails and Fastenings

Initial sorting of the metal fastenings suggested that five centimetres (or two inches) constituted the upper range for iron nails, above which were appreciably larger bolts, spikes and other fastenings. This provided the basis for the major divisions in both the iron and copper fastenings (Table 6.3). Each of these groups was initially further subdivided into subcategories such as nails, screws, bolts and other, but the degree of rust and corrosion affecting the majority of the artefacts made these divisions impractical.

| Material | Length | weight (kg) | % total |

|---|---|---|---|

| iron | less than 5cm (2 inches) | 12.788 | 65.35 |

| iron | greater than 5cm | 5.940 | 30.36 |

| copper | less than 5cm | 0.679 | 3.47 |

| copper | greater than 5cm | 0.159 | 0.82 |

Table 6.3 Metal Fastenings

Iron nails were by far the most numerous fastening, although these were invariably in poor condition and heavily fragmented as a result of the salty, alkaline environment of the site. However, all of those examined show the rose–head and flat shank tapering to a wedge which is characteristic of wrought or forged nails (Varman 1980). Although no attempt was made to count individual specimens, an average weight of 3.4 g obtained from identifiable complete specimens from squares A2, C2, T98, V6 and X2 produces a minimum number estimate of 3761 nails. The larger iron fastenings and spikes varied greatly in form and their functions are uncertain.

The relatively few copper alloy nails are of maritime origin; that is, they are types normally associated with boat or ship construction rather than structural uses in buildings. The most common of the smaller class are sheathing tacks, used to fasten wood or copper sheathing to ships’ bottoms (Figure 6.2). These are characterised by flat, round heads and square shanks tapering to a point, and are up to 1.5 inches (38 mm) long (McCarthy 1983). In addition to clearly identifiable sheathing nails, there are various other nails and tacks in the size class, usually with square shanks and ranging upwards from 0.5 inch (12.7 mm) in length.

Figure 6.2 Small Copper fastenings.

Figure 6.3 Larger Copper fastenings.

The larger copper fastenings are relatively consistent in shape, having square shanks (tapering down to rectangular), and wedge–shape ends, often with a wider or flattened area at the extremity (Figure 6.3). Although most are broken in some way, generally with the head missing, they are consistent with ‘boat spikes’ (or simply ‘spikes’), used for securing large timbers and decking (McCarthy 1983:12).

80Both the sheathing tacks and the spikes are types normally associated with larger vessels (McCarthy 1983), rather than the small and lightly built whaleboats which did not require sheathing. While it is possible that these items were simply kept on–hand for mid–season repairs, this seems an unlikely explanation. Two other possible explanations arise, the first being that these fastenings represent salvage from the 95 ton brig Arpenture which was wrecked within two kilometres of the station in 1849. The other possibility is that John Thomas undertook ship construction or repair which required these fastenings, such as on his schooner Mary Ann. In either circumstance, it is possible that at least some of these nails ended up being used for repairs to the station buildings.

Window Glass

A total of 3.36 kg of flat clear glass, presumed to be window glass, was recovered from across the site. The thickness of these fragments varies from 1.30 mm to 2.12 mm, with a mean (taken from 100 fragments in C6 and V6) of 1.78 mm. These measurements are well within the range for 'Crown glass', a manufacturing method (involving blowing and spinning the glass) which was common until c.1870 (Boow 1991:101). The Crown method produced glass with a maximum thickness of 2.8 mm (1/9th inch), compared to other contemporary and later techniques which had minimum thicknesses of 3 mm (1/8th inch).

Because Crown glass was lighter and attracted lower excise duties, it was the type most commonly exported from England (Boow 1991). It was normally cut into panes of approximately 16 inches (400 mm), although Boow (1991:101) suggests that glass with a thickness of less than 2 mm, such as that seen at Cheyne Beach, was used in smaller panes. By calculating an average weight of 0.35 g per square centimetre from a sample of flat glass taken from squares C6 and TP3, it is possible to estimate that the total area of glass recovered would be 9586 cm2, just less than one square meter. The window glass was concentrated within and immediately adjacent to Structure One (see further discussion below), whilst the small fraction closely associated with Structure Two (100.5 g/ 35 cm2) indicates a presence only slightly denser than the general background scatter (Figure 6.3).

Other structural

The whale vertebrae used for flooring have been described previously. Although several small fragments of slate were found in and around Structure One, these have been interpreted as writing slates, rather than as roofing or a decorative structural material.

Hardware

Architectural hardware was limited to several probable hinges and a padlock. An example from E2 (spit 5) appears to be a complete, if very rusted, two–piece hinge. The other two hinge parts are of the ‘hook and eye’ type (Cuffley 1984). The eye, a 26 cm piece of flat iron with a curled end (which would be fixed to the door) was located in E2 (spit 5), while a matching hook which would be bolted through the door-frame and on which the eye would hang, came from C99 (spit 5), four meters northeast. The latter was in an undisturbed context, although the two items in E2 were in an area disturbed in 1987 and may originally have come from a closer point.

A large padlock was recovered from C99 (spit 3), approximately 10 cm above the hinge. Rust and deterioration meant that further details could not be discerned. The association with either Structure One or Two is unclear, although C99 is only two meters from the latter building's presumed doorway.

Furnishings/Accessories

The only furnishing items were 13 hooded brass tacks, of the type normally associated with leather or fabric upholstery for chairs. These were clustered in several areas, with five in squares Y3, Y4, X4 and Y6, three in T99 and U98, and four in B5 and C6 which are quite close to a final example in D3. Several curved and ribbed fragments of glass from squares T99 (spit1), TP4 (spit 2) and F1 (spit 3) have been tentatively identified as belonging to the bowls of oil lamps.

Artefact Distributions in the Structural Category

The distribution of flat glass in Structure One appears to indicate windows in the vicinity of C7 and V7 on the front or eastern /beach side (Figure 6.4). It is highly likely that a large quantity of window glass remains in the adjacent unexcavated squares. The wider distribution across the site and midden areas could relate to various discard and post-occupation activities smashing and scattering material across the area. Removal and burning of window frames in a later fire could account for the concentration of melted flat glass, vessel glass and iron fastenings in squares Z3 and Z4. Despite rubble limiting the area available for excavation in TP5 (the interior of Structure Two), the density of flat glass is slightly greater than that for surrounding squares. This suggests that there may have been a window somewhere in the building, although it is not possible to determine the location.

The distribution of metal fastenings (by weight) and some hardware items is shown in Figure 6.5. No clear pattern emerges and the nails of both material types may have come from roof, walls or even the floor. The higher densities in U98, U99, T98 and T99 are due, at least in part, to the presence of several larger iron bolts. The concentration within the fireplace (U4), Z3, Z4 and C2, probably represents post–occupation campfires using structural timbers.81

Figure 6.4 Distribution of flat glass.

Figure 6.5 Distribution of nails and metal fastenings.

FOODWAYS

Artefacts associated with foodways easily comprise the bulk of the assemblage recovered from Cheyne Beach, including a diverse range of materials and functions.

Procurement

Ammunition

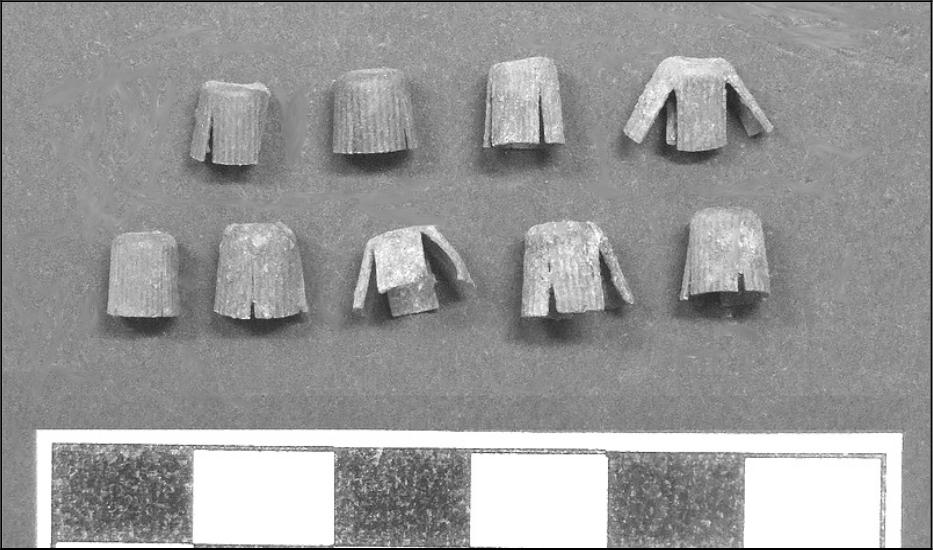

The only artefacts which could be associated with food procurement are various forms of ammunition. Of these, the only firmly identified 19th century items were the 58 copper percussion caps which were found both within the huts and the refuse areas. Percussion caps were a priming charge which replaced the highly erratic flint–lock mechanism. The capsule was placed externally on a piston (or nipple) which would be hit by the hammer, while the actual ammunition, usually a lead ball, was still muzzle–loaded into the barrel (Müller 1980). From the 1850s onwards cartridge–firing rifles began to replace the percussion–locks (Durdick et al. 1981), although sales catalogues show percussion–caps were still available as late as the turn of the century (Sears 1906).

When plotted against known sizes for percussion caps, the Cheyne Beach artefacts, all fall within the range associated with use in a rifle (cf. Hunt 1993:96). There are also two smooth–sided 'top–hat' caps, although both are too badly damaged to measure for the purpose of determining what form of gun they were used in. None of the caps of type showed evidence of head stamps or maker's marks.

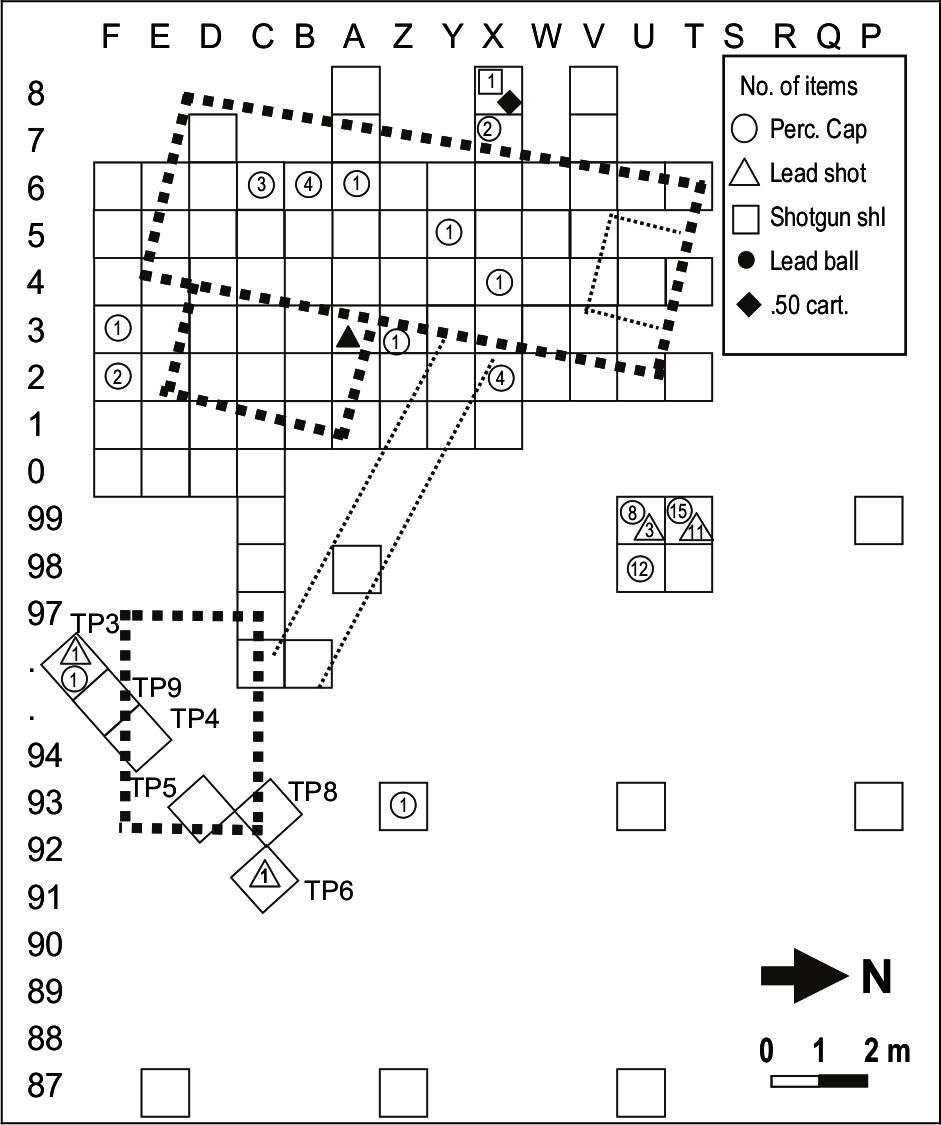

Figure 6.6 Percussion caps.

A slightly deformed lead ball of approximately 0.49 inch (12.5 mm) diameter was recovered from TP3 (spit 3) and may represent a musket ball for use in a 0.50 inch calibre weapon (Scott and Fox 1987). Other ammunition which may be contemporary with the whaling station includes a 0.50 calibre cartridge inches in length, which was recovered from X8 (spit 4). The base of the round is very similar to the "UMC typed–primed" illustrated in Scott and Fox (1987:65), and also shows a centre firing–pin mark. The bases of two shotgun shells (from X8 spit 3 and B4 spit 5) were badly corroded, making it impossible to determine details. Seventeen pieces of lead shot between 0.12–0.19 inch (3–4.8 mm) diameter were also found, mostly in T99 (spit 2) and U99 (spit 2), although there is no certainty that these are not modern pellets which have filtered down through the sandy matrix.

From the upper levels of the excavation were seven modern .22 calibre shells, including one 'short–round' and one unfired example. There was also a single .303 shell 82stamped "1941" on its base. No parts from either 19th century or modern firearms were recovered.

Figure 6.7 Distribution of ammunition artefacts.

The relationship between ammunition, presumably used for hunting purposes, and the faunal assemblage recovered at the site will be discussed later. The lack of fishing gear and agricultural or gardening equipment for tending a cottage garden is noticeable.

Preparation

No baking pans, cooking vessels, or implements such as large knives or utensils which might be associated with food preparation were recovered.

Service

Ceramics

The ceramic assemblage was used in two principal ways during this study. In the first instance it was used as a social and economic indicator, providing a view of the lifestyle at Cheyne Beach and in a broader sense examining the links between the settlement and the wider trade network. The second use, discussed later, was as a marker of discard behaviours across the site.

The ceramics are highly fragmented, with 1568 sherds weighing a total of 4.92 kg. All sherds sorted on the basis of fabric and decoration and where possible conjoined. Due to an absence of sufficient diagnostic elements, minimum numbers were determined on the basis of decoration and the profile of the rim sherds. Because of the high level of dispersion across the site, as shown by conjoins over distances of 11 m or more, unless sufficient of the vessel survived to demonstrate two or more parent vessels, rims with the same pattern and profile were assigned to the same individual. In some cases distinctive patterns, colours or forms allowed a fragment to be identified as an individual vessel despite the absence of a surviving rim.

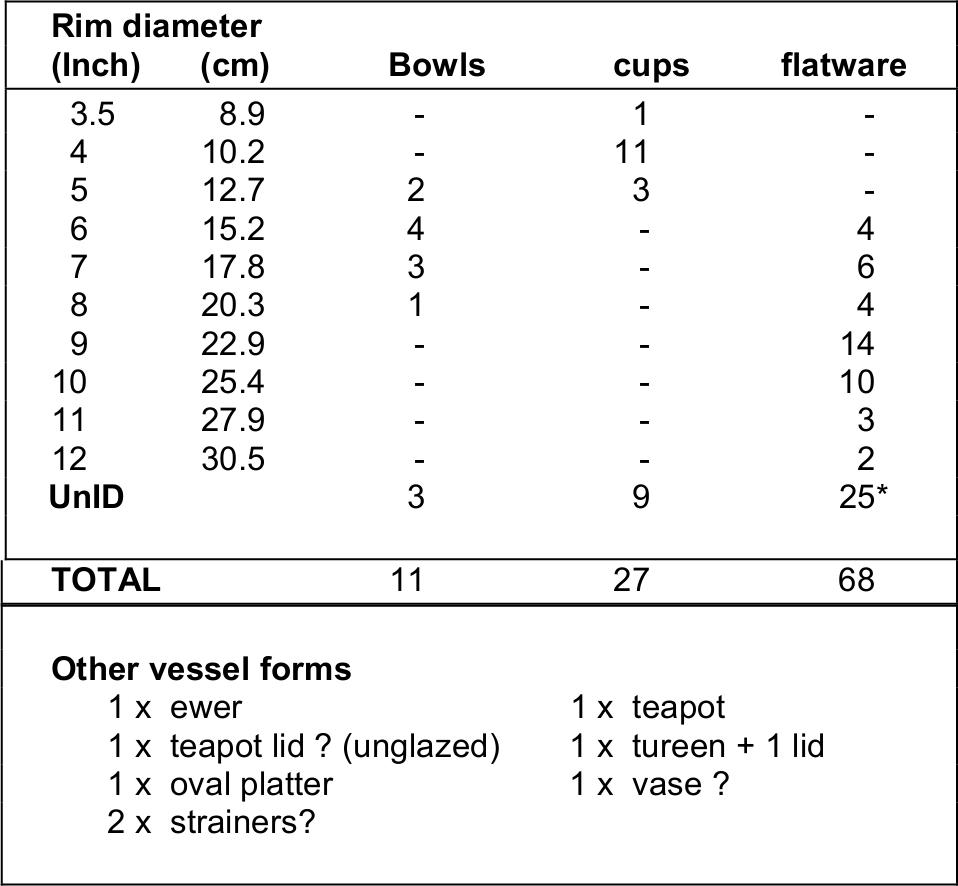

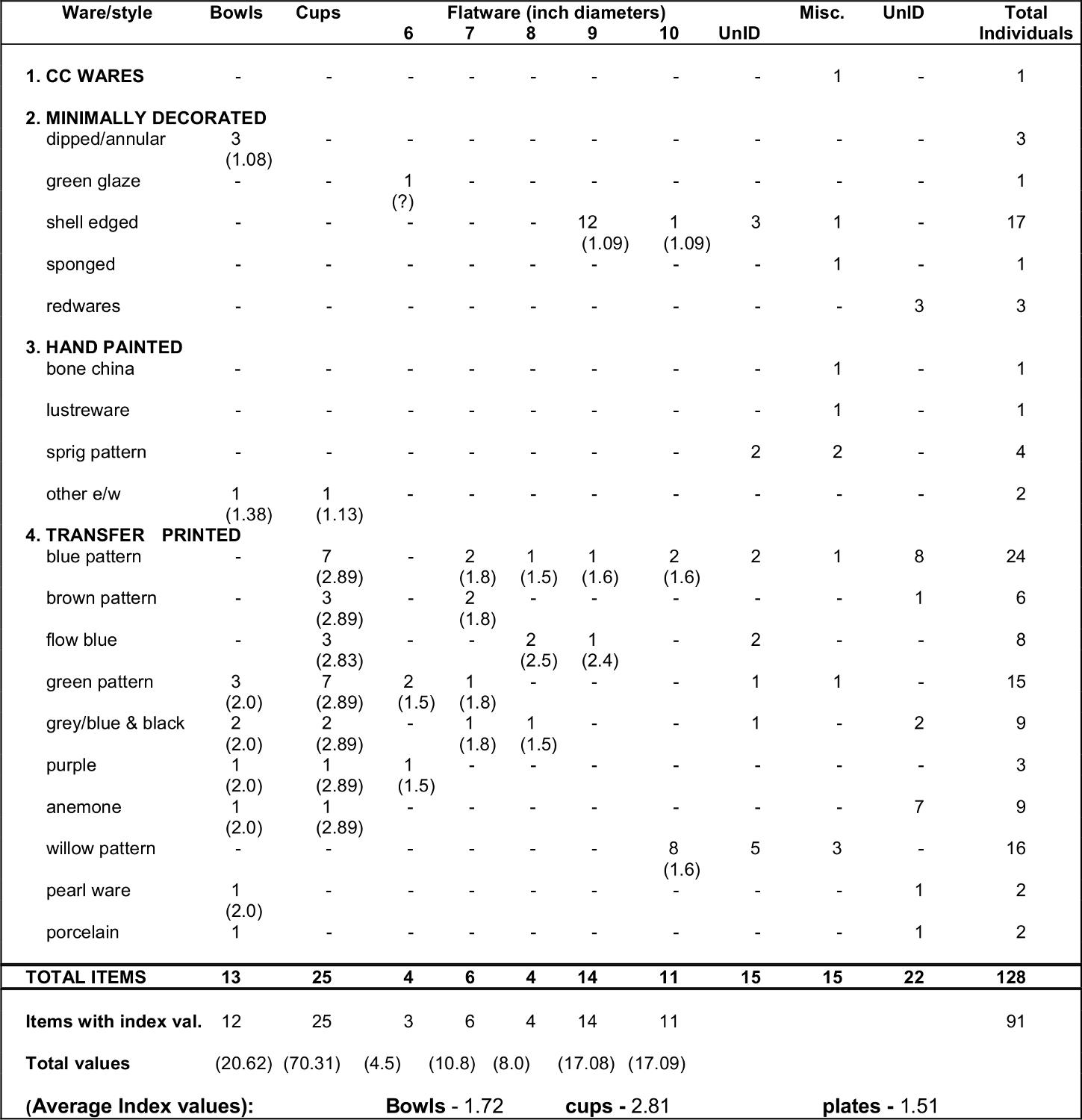

A minimum of 128 tableware items were identified. Tables 6.4 summarises the identifiable forms with reference to diameters of bowls, cups and flatware. It is presumed that many of the fragments which were too small to measure accurately were from flatwares, so that as many as 25 or more further individuals might be added to the 41 items already in this category. An associated difficulty with the fragmentation is determining how many of the smaller flatware items, particularly in the 6 and 7 inch categories, were saucers rather than plates. Although the flatwares have been grouped together, the fact that saucers were frequently purchased with cups, rather than as separate items, may have a bearing upon the calculation of the CC index value, described below.

Table 6.4 Summary of ceramic forms.

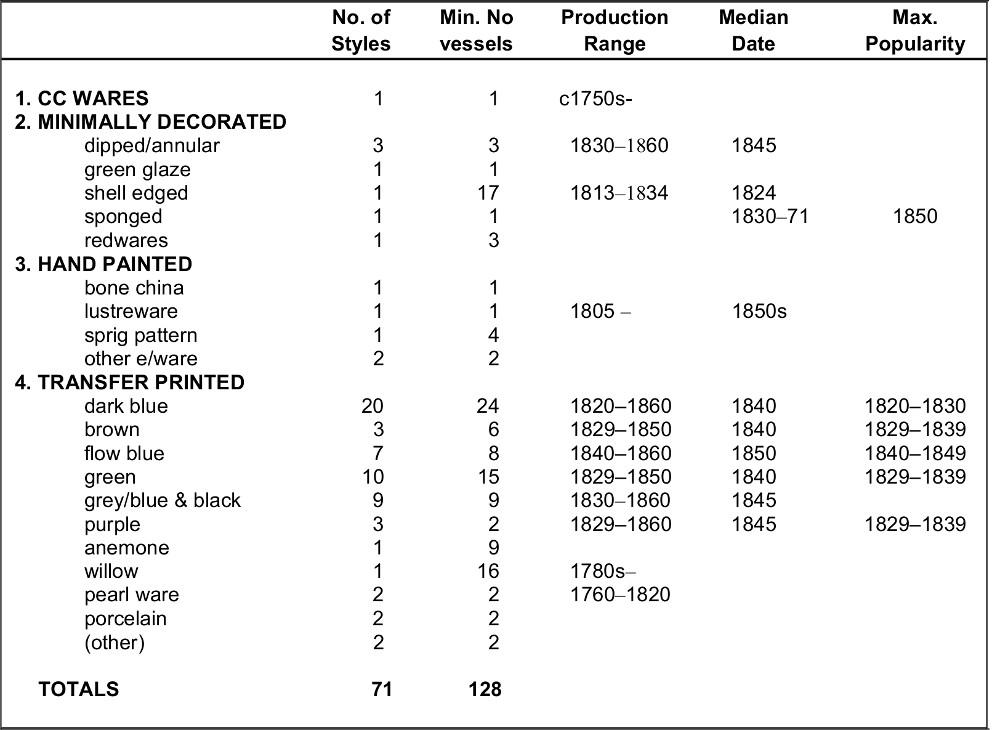

At the time of the original analysis, Miller's (1980; 1991) 'CC Index Values' were still a relatively recent addition to historical archaeology and seen as an effective means of applying a standard measure to ceramic variability within and between sites. Subsequent writers have identified the difficulties with correlating vessel cost with wealth and status, and the importance of context in recognising nuances such as out-of–date purchases, heirloom pieces and other factors associated with the agency of the users (e.g. Brooks 2005; Crook 2005; Wurst 2006:192; VanderVeen 2007). Despite this, Miller’s indices provide at least some notion of where purchases sat on the economic scale. Miller (1980:11) generated his index from English wholesale potters' prices, dividing the cost of 'CC ware' (the cheapest form of refined earthenware, sometimes referred to as 'creamware') into the cost of other forms of ceramic. 'CC 83ware' as the basic unit has a value of 1.00, with the relative cost of other forms varying over time.

Based on this research Miller (1980; 1991) suggested that decoration rather than fabric was the major cost determinant, defining four major categories, from 1 (low) to 4 (high).:

1. Undecorated (CC) earthenwares.

2. Minimal decoration, including shell–edged, sponge decorated, banded, dipped,

3. Painted wares with motifs such as flowers, Chinese landscapes or geometric patterns,

4. Transfer printed incl. willow pattern.

White–bodied wares (slightly more expensive than transfer printing) appeared in the late 19th century, post-dating the site (Majewski and O'Brien 1987).

Following Miller's formula, the index values of the Cheyne Beach ceramics have been calculated by comparing the assemblage against the values for 1858 (Table 6.6), the midpoint of John Thomas's occupation (1846–1869). This 24 year period is slightly longer than the 20 year maximum recommended by Miller (1991). The averaged index values for each class are 1.72 for bowls, 2.81 for cups and 1.51 for flatware/plates. Although the average index value of the flatware might decrease if some of the smaller transfer–printed flatware were placed among the 'cup and saucer' group, this has probably been offset by not including the large number of transfer–printed flatware fragments which were too small for their diameter to be measured. Several teacup handles were recovered which, if they could be associated with particular cup rims, could raise the value for teacups (e.g. Figure 6.8).

Table 6.5 Ceramic decoration, vessel MNI and date ranges (after Stelle 2001)

Although the CC index measures would really only be effective in reference to other Australian sites, a general comparison with U.S. sites (Spencer–Wood and Heberling 1987; Miller 1980) shows Cheyne Beach falling within the medium to high socio–economic range. A further consideration is the uncertainty as to whether the discounting factor used in Miller's (1991) revised index is reflecting a phenomenon only associated with the American market, or whether similar fluctuations in price extended to the Australian market as well (c.f. Crook 2005: 20).

Figure 6.8 Purple transfer print cup and saucer.

There may be as many as 71 patterns or decorative designs in the collection although, despite conjoining, the high level of fragmentation makes comparison difficult. Because of this limitation, a comprehensive identification and dating of specific printed and painted patterns did not prove possible.

84While many of the transfer printed patterns are probably variations of the same scenes, there are also matched or near–matched items within the collection. In particular, there is a minimum of 13–16 shell–edged plates in the 9–10 inch diameter (supper–plate) range. Despite minor variations, they are all of a sufficiently similar style that they could have been used as a set. In the same way, there are also 8–13 of the more expensive willow pattern plates in the 10 inch (table plate) category. There are matches between cups and smaller flatwares (saucers), although not between these and the larger tablewares, which is not surprising since large sets did not appear until the late 19th century.

In addition to cups, bowls and flatware, fragments of several other ceramic forms were recovered (Table 6.4). These included a willow pattern tureen and lid, a transfer printed oval platter, two 12 inch painted plates (possibly platters), a sponged ewer or jug, a willow pattern teapot and an unglazed earthenware lid of the right size to have come from another teapot. Several small fragments with perforated surfaces, some of earthenware and the others of porcelain, may be from strainers although there is insufficient of either to make a positive identification. A final item in the tableware category is a bone china vase, hand painted over a lustre finish.

Table 6.6 Summary of styles, forms and known CC Index Values (in brackets) c. 1858 (after Miller 1980, 1991).

85Although fabric is not necessarily a significant indicator, it is worth noting that there are only three items of porcelain tableware. These include two transfer-printed porcelain vessels (possibly from a cup and another unidentified piece) and the possible strainer mentioned above. The (possible) bone china vase described earlier is the only other vitreous item.

There is little doubt that the Cheyne Beach ceramics originated in England, although there are only four partial maker's marks in the whole assemblage. The first is a brown printed mark on the base of a green transfer printed cup (or small bowl) from square TP9 (spit 3). The legend "COPELAND GARRETT" dates this piece to 1833-47. The second (P99 spit 3) has the words "PEARL ST[ONE]" on the visible portion of the outer oval, with the last three letters of a name, possibly "…NUS" in the middle. This is interesting as this does not correlate with any of the marks incorporating the word 'pearl' listed by Miller (1980:19). Only the far right portion of the third mark, a purple registration diamond on the base of a cup from U98 (spit 2), survives, although the fact that the day of the month is visible means that it comes from the period 1842–67 (cf. Majewski and O'Brien 1987).

The final partial mark (P93 spit 2) has a central crown with ‘[M]EAKIN’ ‘[ENGL]AND’ suggesting the J&G Meakin Staffordshire pottery which dates from 1851 onwards (Godden 1964). However, the use of the name 'England' on the mark could date the fragment to the 1880s or later (Majewski and O'Brien 1987). Unfortunately there is insufficient of the base to determine anything further about the form of the original item. The fragment lies immediately below the laterite road base which covers the area of P93, making its original provenience suspicious. A later date may well indicate association with the Hassell wool store, built somewhere in the vicinity of the car park area in the late 19th or early 20th century.

Table 6.4 lists the broad date ranges for the appearance and disappearance of some of the major ceramic styles represented in the assemblage. Overall, the dates reflect the known occupation of the site, although the midpoints tend to the earlier half. In particular, the even scallops and impressed buds seen on the Cheyne Beach shell edged wares are types generally dated 1813–34, with a median date of 1824. Does this suggest considerable curation, a time lag in supply as a result of the remote situation, or some other mechanism? Dating may also be better resolved with intensive analysis and identification of designs and patterns.

Cutlery

The handles of three cutlery items were recovered, all from exterior squares, although the first two were within close proximity of the buildings. Corrosion has seriously affected the first two pieces (which may be of pewter). The third spoon (U99) is less corroded and may be of electroplated copper alloy. It also shows a common 'tipped' ('Hanoverian') pattern at its head (cf. Sears 1906:109, Smith 1993:193).

| Square | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

| W2/3 | Teaspoon | Impressed "[I]N GE NT IN" |

| TP6/3 | Dinner Spoon | Impressed crown - letters unreadable |

| U99/3 | Dinner Spoon Impressed "*** “. |

Table 6.7 Markings on Cutlery.

Glass Tableware

There are a number of fragments from drinking glasses, tumblers and glass tableware (Table 6.8). It is probable that other small fragments from items in this class have also been have recovered but not identified.

| Square | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| F1/3 | Stemmed drinking glass. | Jones 1989:53 |

| TP3/3 | Tumbler - pressed panels. | Jones 1989:143 |

| TP3/3 | UnID. Press moulded floral panels. | |

| TP3/4 | Decanter. Flanged lip and double neck rings. | |

| Jones 1989:153 | ||

Table 6.8 Glass Tableware.

Storage

Glass Bottles

The most commonly recovered artefacts associated with storage were glass bottles. A total of 20.642 kg of bottle glass was recovered, although a small proportion is associated with medicinal purposes (see below), rather than food and alcohol. Analysis was hampered by the high level of fragmentation and dispersion across the site, with only one near–complete bottle (of a medicinal type) recovered (Figure 6.24). This made reconstruction of bottle forms and examination of diagnostic technological markers extremely difficult. An additional complication was heavy mineralisation of much of the clear and green glass, with a 0.5 mm or thicker crust resulting from the saline environment in which the artefacts were deposited.

Black glass comprised 5.6 kilograms, or 27.16% of the total vessel glass assemblage. Two basic bottle forms were determined; the first being the flat–sided containers associated with case gin, versus the usual cylindrical types. While the flat black glass was separated for analysis where possible, the fragmentation and mixture of the two groups made separate weighing of the two types unreliable.

None of the fragments of flat black glass showed signs of the embossing or ribbing often seen on this form of container and which might have provided further information on distillers or types. Only a single square base was recovered. While a minimum number count using these or other characteristics was not possible, the clustering of flat black glass fragments in different parts of the site (B2, E87, F5&F6, TP3&TP9, U93) suggests that at least five individual bottles are represented. An 86isolated applied lip of deep brown–black glass was also recovered from TP6 and may be from a 'bitters' type square bottle, although the body itself was not recovered.

The other black glass bottle form recovered from the site is the circular form with conical push–ups most normally identified on Australasian sites as 'beer' or 'ale' bottles (e.g. Coutts 1984; Boow 1991). Nine black glass applied lips were also found, rounded in form, with the string–rim collars which assisted a wire to hold the cork in the bottle. While most of the lips do not indicate the original body form (and may in fact be from the case gin bottles), three show evidence of a bulged neck which is consistent with the shouldered type of beer bottle. Other fragments in the collection also indicate the three–piece molding normally seen with this bottle type.

Although an attempt was made to separate 'clear' bottle glass from the various shades of green found at Cheyne Beach, mineralisation and crusting made this discrimination impractical. Most of the glass would appear to be from wine bottles, with a minimum of 11 individuals suggested by the number of complete or partial bases. Seven of these bases have low domes, with at least three having a small mamelon (a small, regular type of pontil scar (Jones 1989), although the presence of these might be obscured by the fragmentary or heat–affected nature of the other bottles. Three bases or fragments have higher 'champagne' kicks. A single base from Y4 (spit 2) has a low dome with an impressed "M" in its centre, suggesting a later origin from the Melbourne Bottle Works, c.1900-1915 (Boow 1991). Bottle glass clearly post-dating the whaling period was excluded from the analysis and distribution shown in Figure 6.13.

Nine whole or partial lips from green bottles were recovered. Eight were applied string-rims, including one example which was 'cracked-off' (Jones 1989). One also has a stopper-finish (or cork-seat) in its neck. A single glass stopper was also found in D0 (spit 3). The bases and necks of the green bottles are consistent with forms associated with wine. The large number of thin, flat scraps of lead recovered from around the site may represent the remains of the lead capsules used to seal some forms of bottle. Unfortunately, these are largely undiagnostic, pre–dating the period when capsule seals were stamped with various details.

In addition to the probable wine bottles, a light–green lip with glass stopper intact and in place was also found. This closely resembles the 'club–sauce' finish illustrated in Jones (1989:88). No other fragments of this container could be identified.

Unfortunately, the minimum number counts for both the black beer and light green/clear wine bottles based on diagnostic elements undoubtedly under–represents the actual number of bottles. Small quantities of black and green glass appear in most squares across the site, often at some distance from the nearest diagnostic piece. However, no attempt has been made to correct this imbalance by using presence/absence of fragments in more distant squares (such as across the midden area), although this has been done for the more distinctive bottle types such as in the medicinal class (see below).

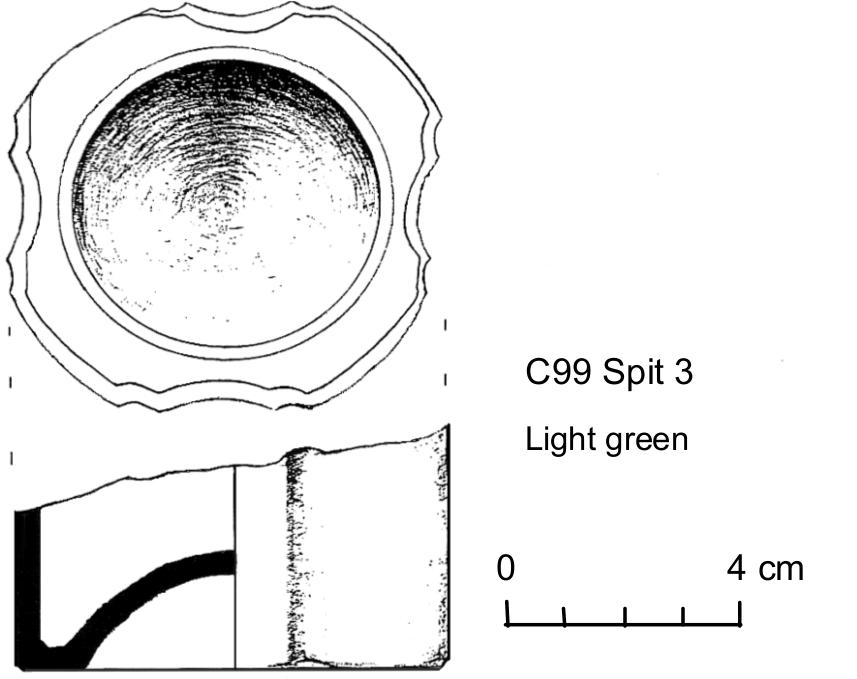

A second major group of clear/light–green glass fragments results from pickle, chutney or vinegar bottles, which are characterised by an octagonal or roughly square cross-section and chamfered corners, and a wide neck (Roycroft and Roycroft 1976). The sides show some variation with concave and recessed panels and moldings. One almost complete base was reconstructed (C99 spit 3) with two other fragments in other areas (TP3 spit 4 and F0 spit 2). However, the total distribution across the site suggests there may be as many as nine individuals represented.

Figure 6.9 Pickle bottle base (C99 Spit 3).

Although no single pickle/chutney bottle can be sufficiently reconstructed to provide a more precise identification, the general class can be seen as associated with food flavouring and a means of making the diet more palatable. It is possible that a small bottle base recovered from T99 (spit 1) may be from a herb bottle.

Stoneware

A single base of salt glazed stoneware bottle of 4 inches (10 cm) diameter was recovered from F2 (spits 4 and 5). There are no distinguishing marks on the recovered portion of base. Bottles of this type are typically associated with stout or ginger beer (Roycroft and Roycroft 1976).

Cask Iron

The wooden cask was the most common form of bulk container for transport and storage used during the 19th century (Staniforth 1987). At Cheyne Beach casks would have performed a variety of functions, ranging from the storage of domestic items (foods, liquids and other commodities), to the industrial function of holding the oil produced by whaling activity.

A total of 5.69 kg of curved iron strapping was recovered, varying in width from 31 mm to 52 mm, and fragmented across the site in no readily detectable pattern. 87The highest concentration was in the area of T99, U99 and U98, with the latter containing 1.76 kg, with a further concentration in F2 (see Figure 6.10). No single fragment was large enough to determine an approximate diameter which might have indicated the type or volume of cask in use, although the bent hoop shown in Figure 6.10 may have originally had a diameter of c.70cm (Staniforth 1987). No evidence of wooden staves was detected.

Figure 6.10 Barrel hoop in situ (F2 Spit 5).

Proximity to the domestic buildings and location away from the beach would suggest that the hoops found were from casks holding domestic items. It is probable that there is an area elsewhere on the site that would have been used for cooperage and may contain further concentrations of iron. During the test excavations at Barker Bay it was noted that fragments of barrel iron increased with proximity to the tryworks.

Distribution of ceramic tableware and glass vessels

Figures 6.11–6.12 illustrate the distribution of ceramics across the site by weight and by number of fragments. The reason for this dual presentation is that there still seems to be some level of uncertainty as to the most appropriate way of analysing and representing artefacts, particularly ceramics in circumstances of fragmentation. In this case there appears to be a close correlation between the measures, although there are several areas in the site where the higher number of fragments versus weight suggests greater fragmentation. These squares are not necessarily close to doors or obvious areas where trampling damage might occur, although more distant squares such as U87 and E87 which are presumably further from regular traffic do have larger pieces.

Most conjoined sherds came from within a radius of several meters of each other (Gibbs 2006, Appendix C.5). However, several examples record greater dispersion, including across distances of 11 m (U99 spit 3 to F2 spit 5) and 16 m (E4 spit 2 and U93 spit 3).

Figure 6.13 shows that glass appears in all squares, although there are several concentrations such as TP3, which contains 2.15 kg, or 9.6% of the total weight of the vessel glass recovered. Four squares within Structure One also show particularly high concentrations of glass. The fragments from B1 and V4 can be reconstructed into three almost complete bottles, two situated in the first square and one in the latter. The completeness of these vessels and their positions within the main structure, resting on the original floor surface in a corner of a room and on the base of the fireplace respectively, suggest they may post–date the whaling station occupation. The concentrations in squares W6 andY6 are also green glass but melted in situ, suggesting they may also originate from a similar early and presumably casual post–whaling occupation. The base impressed with a Melbourne Bottle Works mark (Y4 spit 2) dated to just after the turn of the century can also be dismissed as a later discard, possibly even post–dating the demolition of the building.

If the several concentrations of glass within Structure One are dismissed as post–dating the occupation of the site, then at least one black and five green bottle bases, representing about one quarter of the alcohol bottles, must be eliminated from the minimum number count. Add to this the possibility that other glass in the assemblage may have a similar later origin, and there remain a surprisingly limited number of bottles to represent the 30 years of seasonal occupation by over a dozen men.

Figure 6.14 shows the locations of diagnostic elements used in the estimation of minimum numbers of glass and ceramic vessels. As noted above in the case of the alcohol bottles this was determined from bases, while individual pickle and medicinal bottles were sufficiently distinctive that body fragments could be used. While it is possible a more extensive deposit of glass remains unexcavated, alternative explanations include the use of bulk containers (such as the various types of cask) to transport and store liquids and other foodstuffs, or recycling bottles as a scarce resource.

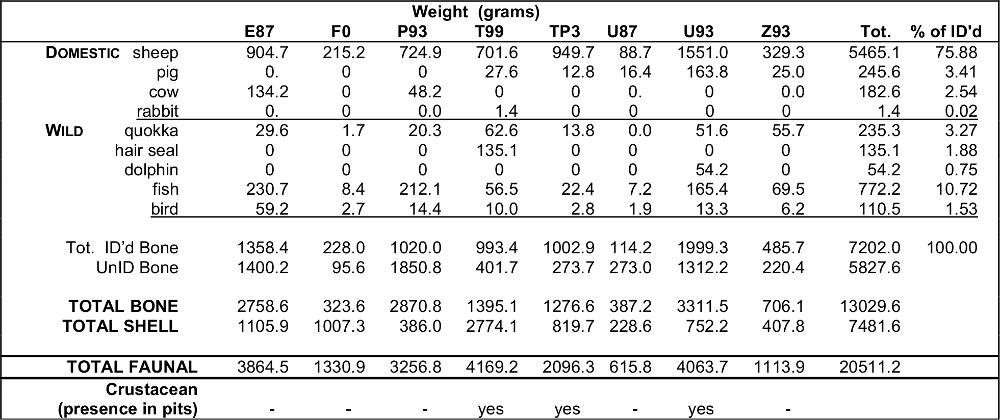

Faunal Remains

The isolation, probable seasonality and industrial nature of the Cheyne Beach whaling station make diet and food supply an area of considerable interest. Of particular importance with regard to questions about adaptation and the relationship between the European settlers and the Australian environment is the use of domesticated versus native fauna in the diet. A version of this analysis is also available in a separate paper (Gibbs 2005).

The aims of the analysis were essentially the same as those expressed by Coutts and Aplin (Coutts 1984:391).

a. Identify the principal taxa,

b. Determine the relative abundance of the taxa and where possible their contribution to the diet,

c. Define some aspects of the butchering, culinary and disposal processes.

Soil conditions at the site were highly alkaline soil conditions (8.0 or higher) resulting in 28.64 kg of bone and 18.41 kg of shell being recovered. Although general sorting, classification and distribution analysis was applied to material from across the site, only the eight pits with the highest density of faunal material were subjected 88to more intensive scrutiny. These squares (E87, F0, P93, TP3, T98, U87, U93, and Z93) contained 45.5% (13.03 kg) of the total bone and 40.6% (7.48 kg) of the total shell (Figures 6.17–6.19).

Figure 6.11 Distribution of ceramic vessels by weight.

Figure 6.12 Distribution of Ceramic fragments.

The enormous body of literature on quantification in archaeological faunal analysis presents varying thoughts on appropriate measures (Reitz and Scarry 1985; Brewer 1992; Lyman 1994). In the analysis of the Cheyne Beach fauna weight has been used to determine the distribution of the several classes of bone and shell across the site. MNI (minimum number of individuals) has been calculated for those parts of the assemblage which are the focus of the analysis. A NISP count was not made, and no attempt was made to determine meat weights.

Figure 6.13 Vessel glass by weight.

Figure 6.14 Vessels.89

| Wt (kg) | % Total | % ID'd bone | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BONE Domestic |

|||

| Sheep, Pig, | 13.621 | 47.56 | 76.38 |

| (med–sized mammal) | |||

| Cow | 0.385 | 1.34 | 2.16 |

| Rabbit | 0.006 | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| Wild | |||

| Quokka | 0.878 | 3.07 | 4.92 |

| Seal | 0.391 | 1.36 | 2.19 |

| Dolphin | 0.054 | 0.19 | 0.30 |

| Fish | 2.265 | 7.91 | 12.70 |

| Bird | 0.235 | 0.82 | 1.32 |

| Total ID’d Bone | (17.835) | (100.00) | (100.00) |

| UnID | |||

| mammal bone frags | 6.483 | 22.64 | |

| bone fragments | 4.321 | 15.09 | |

| Total Bone Weight | 28.639 | 100.00 | |

| SHELL | |||

| abalone | 1.301 | 7.07 | |

| periwinkles | 10.544 | 57.27 | |

| helmet | 0.838 | 4.55 | |

| limpet | 1.006 | 5.46 | |

| olive | 0.235 | 1.28 | |

| thaid | 0.869 | 4.72 | |

| turbo | 0.329 | 1.79 | |

| other | 0.203 | 1.10 | |

| Undiagnostic | 3.086 | 16.76 | |

| Total Shell Weight | 18.411 | 100.00 | |

| Crustacean (present but not weighed) | |||

Table 6.9 Summary of faunal weights.

The initial sorting for bone was based upon the most easily recognised categories of 'fish', 'bird', 'reptile', 'small mammal', 'medium mammal' and 'large mammal' classes, as well as 'unidentified mammal bone fragment' and 'unidentified/undiagnostic bone fragments'. Sea mammals (dolphin, seal) were separated immediately where identified. The detailed identifications undertaken for the eight selected squares were based on comparative collections at the University of Western Australia and from relevant literature including Schmid (1972) and Merrilees and Porter (1979). All shells were identified to species level using Wells and Bryce (1985). A summary of the total weights of bone and shell is provided in Table 6.9. For the purposes of this discussion the vertebral faunal material has been divided into 'introduced' and 'native'.

Introduced Species

Analysis of the eight selected squares shows that the assemblage is dominated by sheep (Ovis aries), providing 5.46 kg of the bone by weight, or 76% of the identified total for these pits. An MNI count suggests the presence of at least 12 animals. For historical reasons (see below) there is a limited chance that the sheep bone includes the osteologically similar bones of goats (Capra hircus). All body parts are present, although under–representation of some elements such as phalanges may indicate discard of non–edible portions in an early stage of butchering away from the site.

The other domesticate identified within the 'medium–sized mammal' bone class is pig (Sus scrofa), although this only comprised 0.24 kg or 3.4% of the total identified bone weight within the eight selected squares. The available body elements do not allow a count of more than one individual, except the teeth, which clearly show at least one juvenile and one (possibly two) adults. That some of the bones come from spatially separated squares may suggest a greater number of individuals, although the majority of the pig bones come from a single square (U93). No other pig teeth were identified elsewhere in the site, although further scrutiny of the 'medium–sized mammal' bone class for the remainder of the assemblage may still produce other bones.

Short sections of butchered cattle (Bos taurus) bones comprise only a minor contribution to the assemblage, providing 0.18 kg or 3.4% of the identified bone weight from the eight squares analysed. The only other Bos body element clearly identified from the remainder of the site is another section of rib (0.17 kg) from U98, bringing the total weight to 0.385 kg, or only 1.3% of the total identified bone weight for the site. No limbs, cranial elements or other body parts, usually readily identified because of their size relative to other domesticates, have been recovered. The limited number and nature of recovered body elements suggests the possibility of salted meats (English 1990).

A small number of rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) bones were recovered, with teeth identified in TP3 (spit 3), B2 (spits 2 and 3), D3 (spit 3), U93 (spit 2) and W2 (spit 2). The presence of open rabbit burrows as well as stratigraphic discontinuities indicating burrowing makes it uncertain if the bones are dietary or later intrusions. Rabbits were successfully released and bred on Mistaken Island (frequently referred to as Rabbit Island) near Albany by George Cheyne as early as the mid–1830s (Garden 1977). A mainland release occurred in the Albany area in 1866, with burrow sightings of at Cheyne Beach from at least 1890 (Stodart and Parer 1988).

A small quantity of bird bone was recovered from the sample squares, although most of this was hard to identify further (see below). While no domesticates were identified from the eight analysed pits, chicken bones were noted in several other squares elsewhere in the site (e.g. B6 spit 1, U98 spit 1).

Native Species

The native terrestrial fauna almost exclusively comprises of the remains of quokka (Setonix brachyurus), a type of small wallaby. Quokka provides 0.24 kg or 3.3% of the total identified bone in the selected squares, with an MNI of two based on right mandibles recovered from E87 (spit 3) and U93 (spit 2). For the site as a whole, quokka contributed 0.88 kg, comprising 3% of the total bone. A total of nine right mandibles were recovered from across the site indicating a minimum of nine individuals, 90although wide spatial separation may mean that at least 11 individuals are represented. A more comprehensive examination of other body elements could provide a higher figure.

Figure 6.15 Quokka jaws (Setonix brachyurus).

Quokka were once available in scrublands throughout coastal southwest Western Australia, but their range has now been restricted to relict populations on Rottnest Island, Bald Island (4km SE of Cheyne Beach) and several small mainland sites including the Waychinicup Valley (8 km SW) (Storr 1965).

A single tooth from a larger macropod (P93 spit 4), could not be identified to species level. A portion of a Macropus sp. mandible, also insufficient to make an identification, was recovered with other 19th century artefacts from the surface of TP1, which was located at some distance north of the site and in a context which suggest the material may have been re–deposited.

Several species of large macropod, including brush wallabies (Macropus irma) and grey kangaroos (M. fuliginosus), are available in the general area, but are uncommon in the sand plains immediately behind Cheyne Beach (Storr 1965).

Skeletal evidence from the midden deposits indicates that both dolphins and seals were at least occasionally slaughtered for dietary purposes. Fragments of a lower right mandible of a dolphin were recovered from U93 (spit 4). Although the jaw is incomplete, the number of tooth sockets and the tooth size of 3 mm or less in diameter suggests that it may be from a common dolphin (Delphinus delphis) (Baker 1990). Fragments of four large tympanic bullae, part of the auditory structure of mammals, were also recovered (F2 spit 5, U98 spit 2, and two from T99 spit2). Although a firm identification has not been made, these probably originate from hair seals (Neophoca cinerea), which are commonly seen on Bald Island as well as occasionally coming ashore on the mainland around Cheyne Beach (Storr 1965; Westerberg pers. comm. 1990).

Whale bones and fragments (as opposed to the whalebone or baleen strips described in Chapter Three) were recovered in varying quantities from most squares across the site, with the exception of the eastern and northern pits on the edge of the midden. This material is almost certainly present as a result of structural uses, such as the whale bone floors in both buildings, rather than as a result of dietary uses (discussed below).

Highly fragmented bird bones account for a very small proportion of the Cheyne Beach faunal assemblage, with a weight of approximately 0.24 kg, or only 1.3% of the total identified bone weight on the site. In the eight sample squares this rises only slightly to 1.5% from 0.11 kg of bone. The lack of diagnostic elements within the sample squares makes for some difficulty in discussion, and identification of native species will have to await a specialist study of the faunal assemblage. Biological surveys have identified a variety of potentially edible species in the area (Smith 1977), although the most likely candidates are the several nesting and burrowing species on Bald Island. These include brown quail (Synoicus ypsilophora), little penguin (Eudyptula minor), and great–winged petrel (Pterodroma macroptera). The remains of fleshy–footed shearwater (Puffinus carneipes), commonly referred to in Western Australia as the muttonbird, have also been found on Bald Island, but no burrows have been identified.

The skeletal evidence suggests that the most commonly consumed native fauna at Cheyne Beach was fish. The 0.77 kg of bone recovered from the eight sample squares provided 10.7% of the identified total for those pits, while for the site as a whole the 2.26 kg of fish bones recovered represented 12.7% of the total identified bone. Identification of fish species within the sample squares was made on the basis of diagnostic cranial material. A number of otoliths were recovered and have been identified as whiting, most probably King George whiting (Sillaginodes punctatus). All the otiliths suggest quite large specimens.

Despite the limited identifications made from the faunal assemblage, it is clear that fishing provided a significant staple component of the diet. Cheyne Beach is now a popular and well regarded fishing spot, with the reefs and granite ledges near the site yielding a wide variety of highly edible species on a year–round basis.

Several shark teeth were found in the deposit, including one in square E87 (spit 2) and two in C0 (spit 1). Historical evidence and observations of modern whaling operations show that sharks were strongly attracted to whaling stations, often feeding off the carcasses as they were being brought into shore and while anchored in the shallows.

Whenever whales were cut in Frenchman's Bay, we boys used to have some exciting times killing the sharks that were after the blubber; for the purpose we used the cutting–in spade (McKail 1927). 91

Table 6.10 Summary of faunal weights in sample squares.

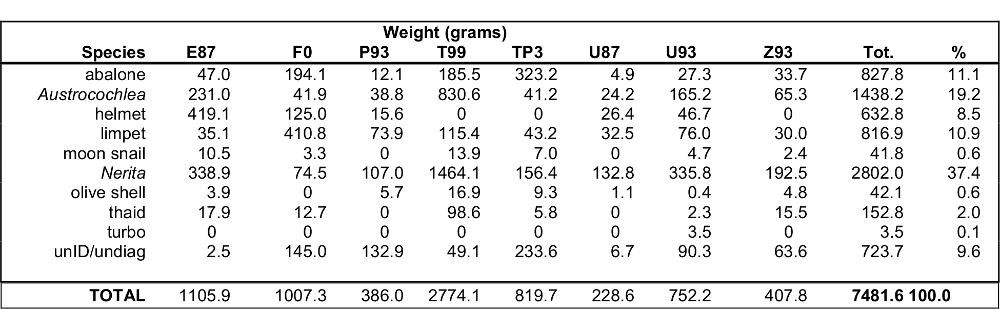

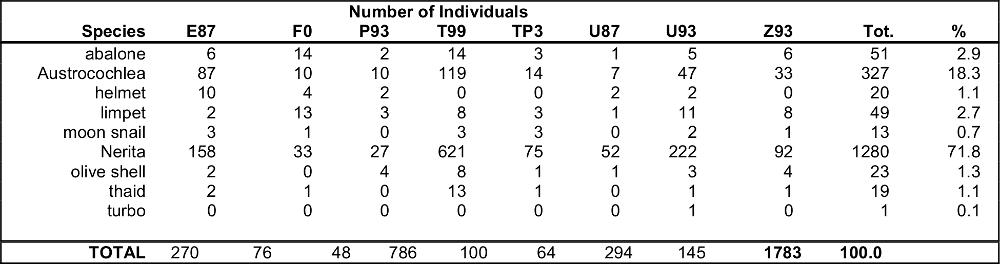

Table 6.11 Total weight of shells recovered from Cheyne Beach, including known environments.

Table 6.12 Shell weights (grams) in sample squares.

Table 6.13 Minimum numbers of shells in sample squares.

92The equipment list for Carnac includes 24 fishing lines and 20 shark hooks (see Figure 3.2), supporting the probable use of shark as a dietary item.

Figure 6.16 Shark teeth.

Small quantities of crab shell were recovered from 11 squares spread from the eastern edge of Structure One and through the midden area (square C1, C5, E1, T99, U2, U93, U98, U99, X8, Z3, TP3). This evidence was limited to the tips of claws (dactyls), which are insufficient to make any identification to family or species level.

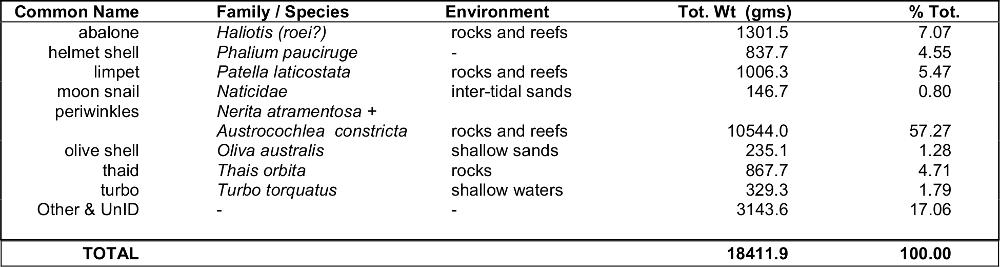

Shellfish

The small reef and granite shelves of the headland adjacent to the whaling station appear to have provided several varieties of shellfish. Table 6.11 provides a summary of the main species (by weight) recovered.

During the general sorting Nerita atramentosa and Austrocochlea constricta were grouped and weighed together, being of similar size, form, and environment, and generally being commonly identified as 'periwinkles'. For Tables 6.12–6.13 these two species have been counted and weighed separately. In addition to the species listed, single specimens or low numbers of several other shell species with possibly dietary use were also recovered, including tritons (Charonia lampas), tun shells (Tonna variegata), and Camapanile symbolicum, which apparently has no common name.

While it was not possible to undertake a minimum numbers count for the whole site, Tables 6.12 and 6.13 present a comparison of shell weights and numbers for the sample pits. Although no attempt has been made to calculate meat weights, Nerita, even without the Austrocochlea component, clearly comprises the bulk of the shell, followed by abalone and limpet.

Butchery and Disposal

Analysis of butchery marks and skeletal element representation was undertaken primarily to determine whether domestic species had been kept live on or near the site or brought in pre–prepared, probably as salted meats. Native terrestrial and marine fauna remains were not examined for butchery.

Figure 6.17 Distribution of animal bone.

Figure 6.18 Distribution of shell.

As noted previously, virtually all body elements of sheep are represented, which is suggestive of butchery on–site, probably as a function of keeping meat 'on the 93hoof' (a detailed breakdown of elements is available in Gibbs 1995: Appendix C). Most of the bones are broken, with only two unbroken long bones in the whole sample, although some of this may be a result of post–depositional factors. Visible cut marks are only present on 19% of the sheep bones and 4% of the pig bones recovered. Although a detailed analysis of butchery patterns such as that undertaken by Ritchie (1986) would be useful, this current study was constrained to making only preliminary comments on the most notable or frequent cuts.

a. Crania: There was a considerable quantity of cranial material, mostly visible as whole or partial mandibles and maxillae, with many more free teeth. The craniofacial portions of the skulls were normally highly fragmented, although one example clearly shows the top of the calvarium neatly sawn off, presumably for the purpose of cleanly removing the brain. Mrs. Beeton's Cookbook (1861) contains several recipes for sheep's head and sheep's brains (en matelote) which might require this.

b. Vertebrae: All of the five epistrophei (axis vertebrae) recovered had been cut at various angles as a means of removing the head. Most of the other vertebrae had been cut longitudinally as a result of splitting the carcass in half.

c. Scapula and Humerus: The scapulae have frequently been cut across or near the articular surface, with some corresponding cuts across the end of the humerus. This might be a by–product of the removal of the neck as a separate cut. The scapula and humerus would normally be included in the forequarter cut (McVicar 1993).

d. Radius. Cuts at the distal and proximal ends of the radius were probably to acquire the fore shank cut and to separate the extremities, although in the sample collection it was noted that these breaks were usually along the shafts, rather than in close proximity to the epiphyses. Metacarpals and phalanges were recovered in low numbers.

e. Ribs: Ribs appear to have suffered most from post–depositional breakage, which includes their removal from the archaeological context. Those fragments with visible cut marks suggest that at least in some cases divisions were made both towards the proximal (head/articulated) end and towards the distal end, possibly to provide more manageable portions. The distal portions themselves were probably included in the breast cut.

f. Pelvis and Femur: Cuts through the pelvic bone tend to be close to or through the acetabulum, although some of the bones from the sample squares showed divisions slightly lower (through the ischium) and much more rarely higher, through the ilium (hip bone). Most of these fragments were also broken, although these cuts would indicate removal of the chump. There does not appear to be particular evidence of further cutting into chops. The proximal joints of the femurs bear corresponding marks, while divisions through the distal joints suggest division into a leg cut.

g. Tibiae and rear extremities: There was an almost equal number of breaks at the proximal and distal ends of the tibiae, separating the hind shank cut and removing the rear extremities. Several metatarsals were also recovered.

Figure 6.19 Distribution of mammal bone.

Figure 6.20 Distribution of fish bone.

From the evidence of the eight sample squares, it appears likely that the sheep were slaughtered and butchered at the site, rather than brought in as prepared and salted meats. The meat cuts suggested by the bone 94breakages are similar to those which might be expected for a European diet (McVicar 1993), although as noted the position of the divisions are sometimes away from the joints, presumably reflecting the fact that this was not done by a professional butcher. While no attempt was made to determine the ages of the sheep represented in the deposit, many of the bones had un–fused epiphyses, suggesting that both lambs and older animals were consumed.

In contrast, there is limited quantity and variety of bones from pig; mostly upper body and cranial elements, with the exception of a single fragment of pelvis. Cattle bones are even more limited, and comprise predominantly of short sections of rib, possibly indicating these were cut to fit into a barrel, which was the normal means for transporting prepared and salted meats (English 1990).

Less than 20 of the bones and fragments were burnt or charred, and even this may well have been post–depositional burns rather than a product of cooking. Given the close proximity of the midden to the cottage and kitchen, disposal of hot ashes onto the bones, or even a periodic deliberate fire to reduce the smell or volume of rubbish, may have been possible. Potential scavengers impact is discussed below.

Artefact Discard in the Foodways Category

Discard patterns for bone and shell are represented in Figures 6.17 and 6.18. While both classes have similar distributions across the site, a greater proportion of bone is present in the midden pits (P93, U93 and Z93), while shell is focused slightly closer to the buildings. Figures 6.19 and 6.20 compare the distributions of mammal bone and fish bone, with the latter increasing in density towards the middle and far edge of the midden. Two concentrations of fish bone within Structure One, at X6 and Y3, correlate with the concentrations of glass which are thought to result from an early post–occupational use of the building.

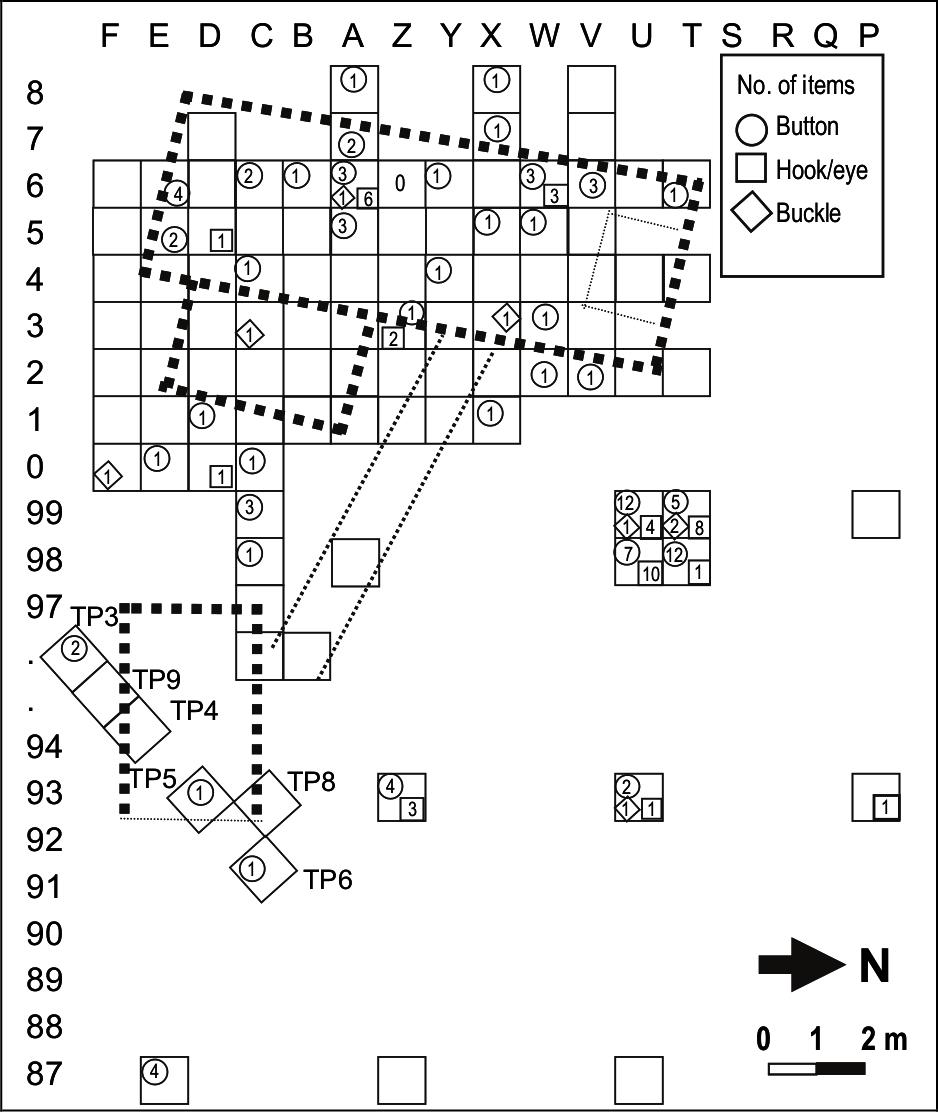

CLOTHING

Fasteners

Buttons

The clothing worn by the occupants of Cheyne Beach is best represented by the variety of fasteners found, including buckles, buttons, hooks and eyelets. Buttons are the most numerous form of fastening, with 99 whole and broken examples. These were classified into 30 types on the basis of material and stylistic characteristics, described in Appendix C.5 and summarised in Table 6.14. Only a small number of the metal buttons exhibit more diagnostic characteristics, such as manufacturer's names (Table 6.15), although it has not proved possible to date these.

| Material | Description | No. of types | Tot |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bone | 4 hole / 1 piece | 4 | 15 |

| Glass | 2 hole / 1 piece | 1 | 1 |

| 4 hole / 1 piece | 2 | 12 | |

| Shell | 2 hole / 1 piece | 2 | 4 |

| 3 hole / 1 piece | 1 | 1 | |

| 4 hole / 1 piece | 5 | 15 | |

| Metal | 2 hole / 1 piece | 3 | 9 |

| 4 hole / 1 piece | 3 | 12 | |

| 2 hole / 2 piece | 2 | 7 | |

| sew-through / 3 piece | 1 | 1 | |

| soldered loop / 3 piece | 3 | 9 | |

| too rusted to determine | - | 9 | |

| Composite | shanked/metal w. fabric cover | 1 | 2 |

| soldered loop/metal w. | |||

| glass insert | 1 | 1 | |

| sew-through/metal and UnID | 1 | 1 | |

| Total | 30 | 99 |

Table 6.14 Summary of button types

Two of the more interesting items are two two–piece metal buttons with wire loops from squares U98 spit 2 and E1 spit 5. The former appears to be a British naval button, 8 mm in diameter, slightly raised with an anchor and cable within a circular 'rope' rim, but without the crown which characterises naval buttons after 1832. This example most resembles an 'unauthorised' button, in particular a surgeon's button from the 1827–1832 period illustrated in Lewis (1945:136). The second button is of similar size and motif, but is flatter and without the rope rim.

| Square | Description | No. |

|---|---|---|

| T99 s1 | Braces/suspenders buckle. Triple tang. | 1 |

| Brass. Impressed | ||

| "REGISTERED 25 AUGUST 1856" | ||

| A6 s.2 | Braces adjuster? Brass. | 1 |

| X3 s.2 | Serrated buckle. Brass. Leaf/fleur design?. | 1 |

| C3 s.2 | Single tang roller buckle. Iron? | 1 |

| U93 s.4 | Double tang, roller (external) buckle. Iron?. | 1 |

| F0 s.4 | Double tang, roller (external) buckle. Iron?. | 1 |

| T99 s.1 | Double tang roller (external) | |

| buckle. Brass. | ||

| U99 s.2 | Button Hook?. Brass. Light leaf pattern. | 2 |

| Impressed "C. ROWLEY PATENT" on rev. |

Table 6.15 Buckles.

Buckles and Clothing Hardware

In total 19 hooks and 27 eyelets were recovered, with some variation in size evident. The five clothing buckles from Cheyne Beach are similar to the more common iron and brass examples in Cameron's (1985) types A, C and D, which include both tanged and serrated edge varieties. In addition, there were two brass braces–adjusters, and a probable braces fitting through which a metal button would be hooked. 95

Figure 6.21 Buckles.

Figure 6.22 Thimbles.

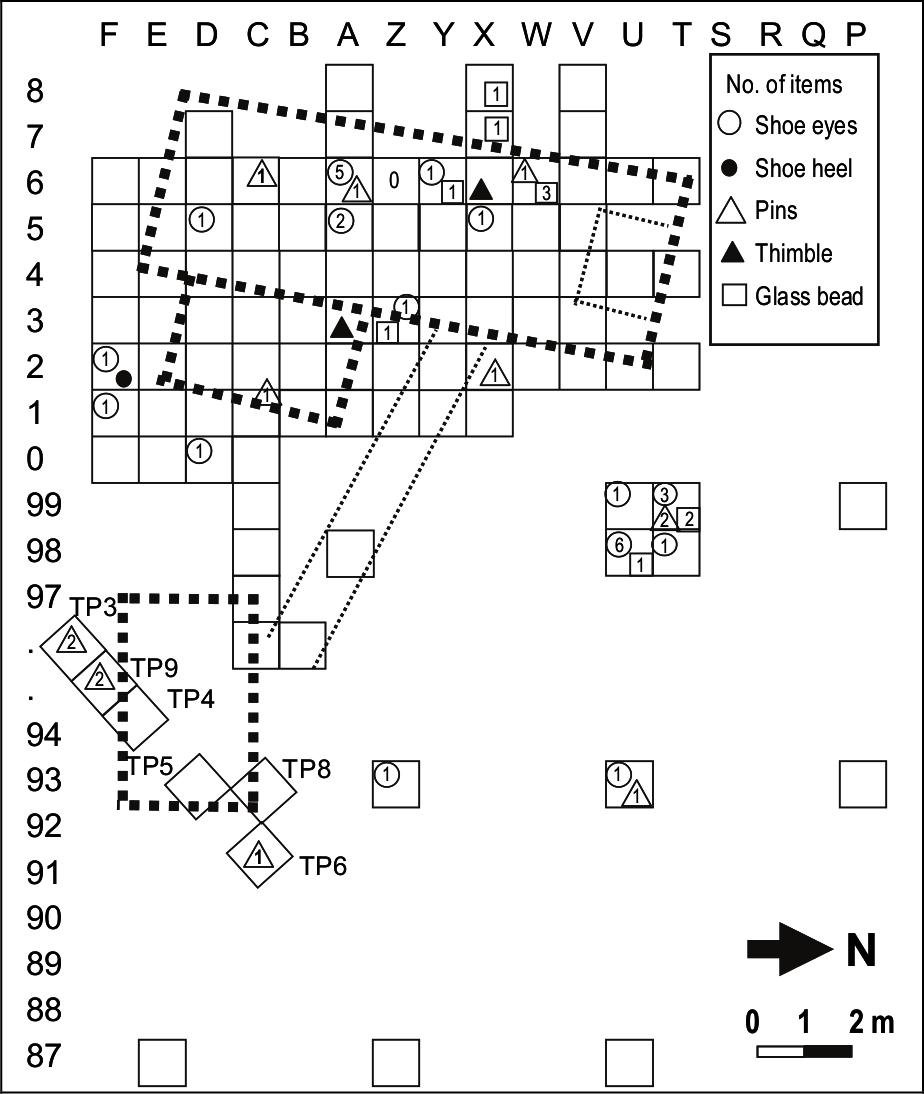

Manufacture

Thimbles and pins represent the only items clearly associated with clothing manufacture or repair. Two brass thimbles were recovered from within Structure One (squares A3 and A6 – see Figure 6.24). The 13 dressmaking pins were found both within and outside of the structures. These range in length from 31 mm to 34 mm and one 64 mm example, with several forms of round, tapered and flat head (c.f. McGowan 1985).

Other

Glass beading

Nine small glass beads were recovered from the site, in diameters of approximately 2 mm, 3.5 mm, 4 mm and 5 mm. These are the smallest cultural items recovered from Cheyne Beach, with a high probability that an unknown number passed directly through the standard 3 mm and 6 mm sieves used during the excavation. Four colours are represented, blue/green (4), amethyst (3), white (1) and amber (1), with various shades within each group. Beads of this type might also be attached to clothing and other items of apparel.

A badly deteriorated fragment of boot heel was excavated from F2 (spit 5). This consists of four layers of leather, of approximately 4 mm thickness each, held together with 18 small iron tacks. Several other small scraps of leather, probably parts of the same fragment, were also found in close proximity, although there is no evidence of the body of the shoe, other than two eyelets from F1 and F2.

Figure 6.23 Distribution of clothing items I.

Figure 6.24 Distribution of clothing items II.

96Whalebone strips

Several short strips of a semi–flexible dark brown material, 5 mm wide, were recovered from F0 (spit 3) and F1 (spit 4). Although not of the thickness or width of whalebone stays examined in museum collections, the flexibility itself suggests this material. While collection of whalebone was one of the functions of the station, the provenience of these pieces makes them more likely to have been from an item of clothing.

Artefact Distributions in the Clothing Class

Figures 6.23 and 5.24 describe the locations of the majority of clothing related artefacts. A scatter of small items is seen throughout the interior of Structure One, particularly around square A6, although the main concentration is in the four squares (T98, T99, U98, U99) located some distance from the doorway.

PERSONAL

Medicinal and Toiletries

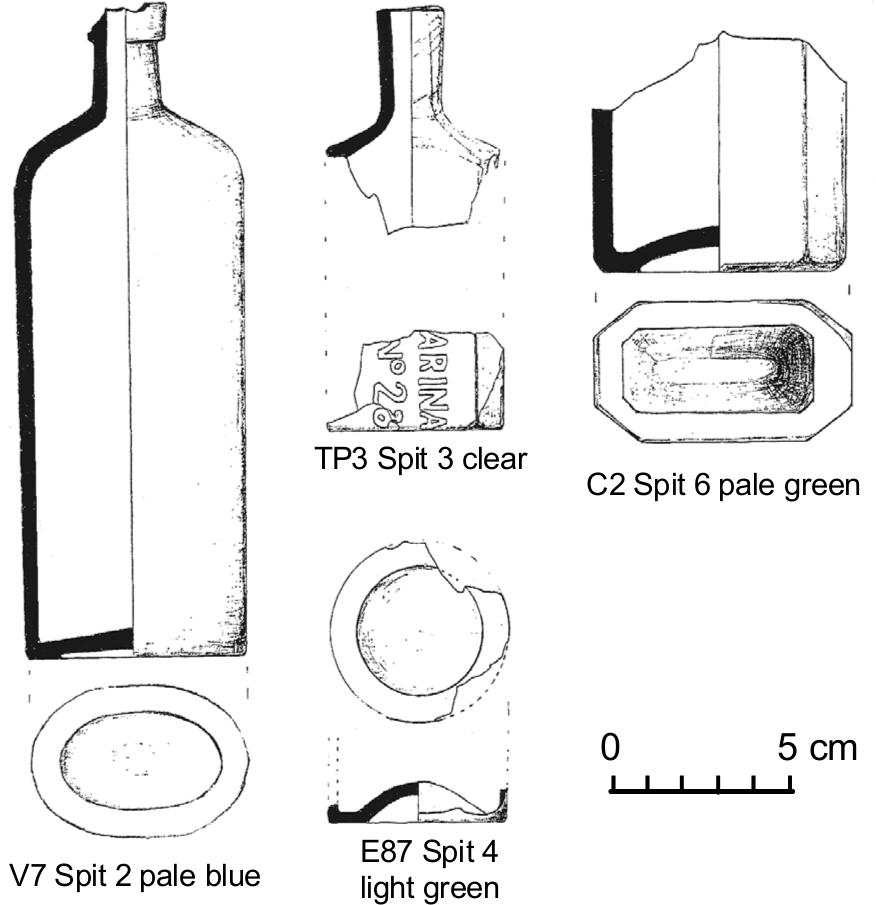

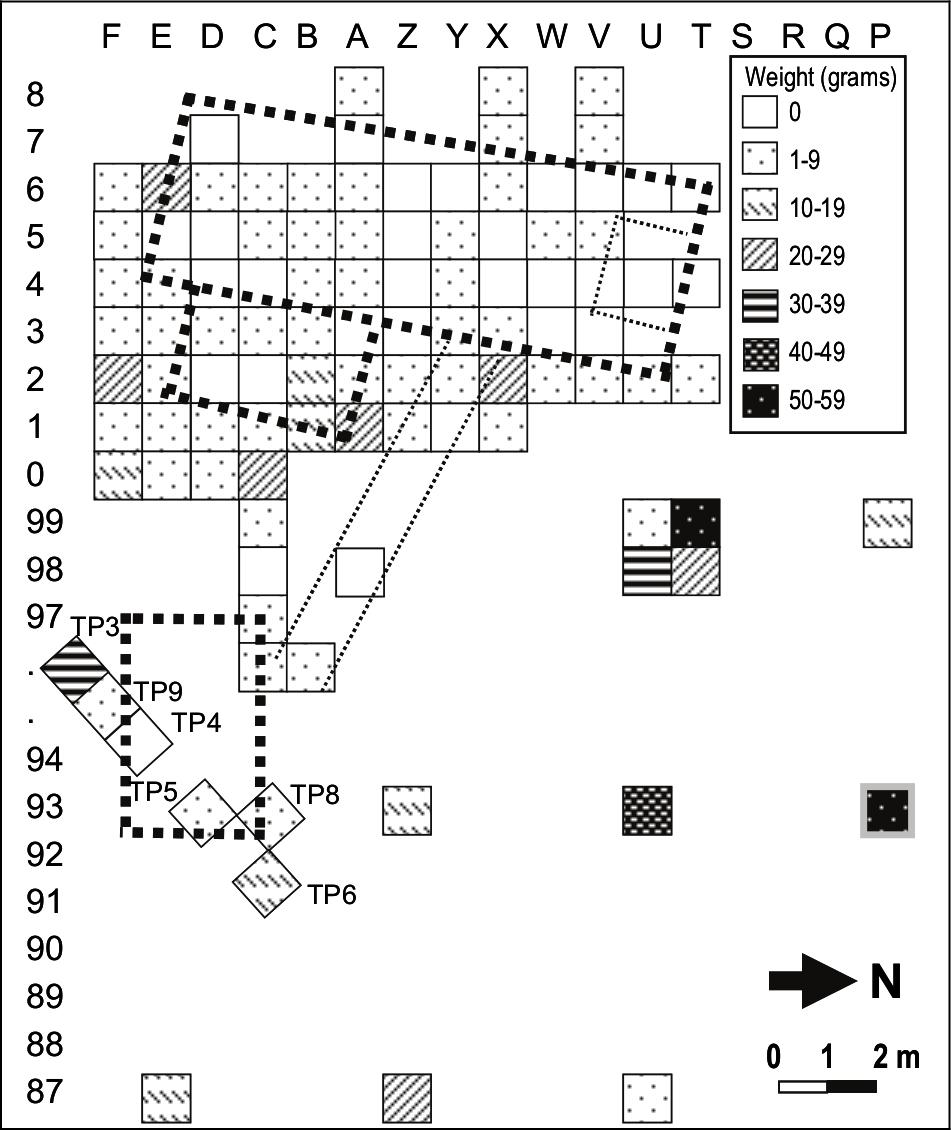

The most common evidence for the use of medicines by the inhabitants of Cheyne Beach is provided by the remains of small glass bottles, described in Table 6.16.

In most instances individual bottles are represented only by a few fragments. All conform to the general shapes associated with patent medicine bottles for this period, although the several pieces which exhibit embossed lettering do not have sufficient to allow identification. As shown in Table 6.16, the fragments have been grouped to provide a minimum number of 13 probable medicinal or toiletry bottles.

Figure 6.25 Medicinal bottles.

Table 6.16 Medicinal and toiletry containers.

Figure 6.26 Combs.

Also within the medical category are pieces of white granite earthenware which originate from ointment pots or lids. The fragments of three small ointment jars and one larger–size lid would all appear to be from the ubiquitous Holloway’s Ointment. Although it was not possible to determine precise dates, the Strand address partially visible on the three smaller jars (representing two different designs), dates them before 1867 (Roycroft 97and Roycroft 1977:25). The distribution of fragments suggests a minimum of 10 ceramic ointment containers

A fragment of the rim of a chamber pot, recovered from U87 (spit 3), might also be included in this category. The rim suggests a diameter of 10"/25.4 cm and is of a plain cream glazed earthenware with a flat upper rim embossed with a feather design.

Cosmetic

Combs

Fragments of several combs were recovered from the site, all made of an unidentified black material. Suggestions have included an early celluloid (although this would date from the 1870s onwards), or possible gutta percha. These include a fine–tooth comb with 19 mm long teeth from U98 (spit 2), and small piece from the back of another fine–tooth comb (with no remaining teeth) from X8 (spit 4) (Figure 6.26). Eight 22 mm long teeth from a larger comb were recovered from T98, T99, U98 and U99, with a further single tooth of similar size and type found in U7 spit 2, 8 m west.

Recreational

Toys and Gaming pieces

A number of small items suggestive of gaming activities were excavated from within Structure One, with particularly notable items being a small bone die and a Chinese coin, both found in Y5 (spit 3). The die is badly deteriorated, although the irregular dimensions (11.0 mm x 10.1 mm x 10.4 mm) and uneven placements of the dots on the faces strongly suggest that this was home–made. An artefact found in U98 (spit 2) looks as if it were in the process of being squared, possibly for use as a die and appears to be either ivory or a fragment of a large tooth, possibly whale or seal (Figure 6.27).

Figure 6.27 gaming pieces.

The Chinese coin is copper, measures 24.8 mm (0.983") in diameter, but is damaged, with the normally square central hole being roughly cut and dented out of shape (Figure 6.28). The two characters on the reverse can be read as "Boo–ciowan", indicating that it was minted by the Board of Revenue in Beijing (Krause and Mishler 1988). The right and left hand characters on the obverse are "T'ung–pao", or 'universal value', meaning that the coin was legal tender throughout China (Ritchie 1987). The deformed central hole and wear along the face obscures the top and bottom characters which contain the name of the emperor at the time it was struck. This is, unfortunately, the crucial element for dating purposes. However, it is possible that it is a coin from the Ch'ien Lung period with the emperor Kao Tsung (1735–1796), and may be of a type known as ‘coin of celestial benefit’ (Cresswell 1979:44). It is unlikely that this piece performed a monetary function, possibly being kept as a gaming token or lucky piece.

Figure 6.28 Chinese coin – face and obverse.

A 6 mm thick fragment of rectangular bone with six regularly spaced and deeply drilled holes may also be associated with game purposes (Figure 6.27). This piece, found in D7 spit 2, bears resemblance to a peg–board used for cribbage, although this is by no means a certain identification. Two bone pegs of 22 mm (13/16ths") in length, but each split in half down their length, were excavated from E87 spits 3 and 4. These may be associated with gaming purposes, or may have some other as–yet unidentified function not associated with recreational purposes.

Figure 6.29 Harmonica.

Marbles were a highly popular game during the 1860s and 70s, and consequently have been found on a variety of 19th century Australasian sites As noted by (Birmingham 1992). The first of the two examples found at Cheyne Beach (T99 spit 1) is a 'stoney' of brown clay 98with swirls of orange and red/maroon, and a diameter of 14.8 mm (0.58"). The other is white with faint grey swirls, possibly earthenware, of 19 mm (0.78") diameter, and may be an 'alley' (TP3 spit 1). The final artefact within the 'toy' category appears to be a fragment of a small porcelain saucer from a child's tea set (C99 spit 2). Unfortunately, no further pieces from this set have been identified.

Musical Instruments

Several fragments of the sound–board of a harmonica were excavated from U98 spit 2 (Figure 6.29). The reeds are brass, while the base plate is possibly a lead alloy, similar to an example excavated at the mid–1860s site of Omata Stockade in New Zealand (Prickett 1981). Small fragments of wood with iron clasps were closely associated with these, and would appear to be the remains of the body. Single brass reeds from another harmonica or similar wind instrument were also found in squares V5 (spit 3) and X8 (spit 4).

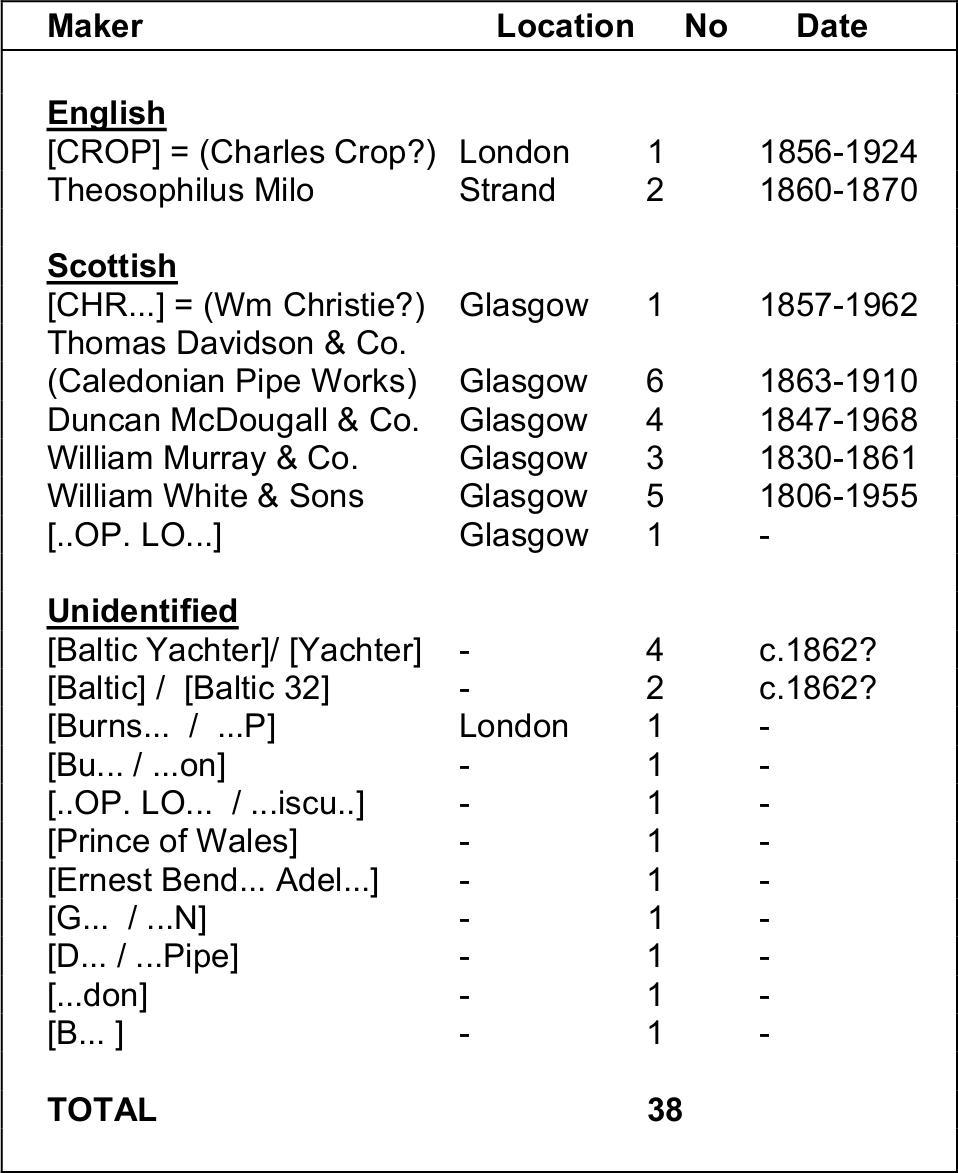

Clay Tobacco Pipes

Fragments of clay tobacco pipes were found throughout the site, with Table 6.17 summarising the key attributes identified during the study. A minimum number count was attempted using several different attributes, including stem/bowl joins, lips (mouthpieces), and bowl rims. The stem/bowl junction provided a count of at least 36 individuals, although there are at least 38 stems with makers' marks. A comprehensive analysis using combinations of attributes would undoubtedly increase the minimum number.

| Attribute | No. |

|---|---|

| Bowl/stem joints (min. no. count) | 36 |

| Number of stems with makers marks | 38 |

| Min. no. of decorated bowls | 18 |

| No. of decorated stems | 2 |

| No. of feet/spurs | 10 |

| Lips | 22 |

| Sharpened stems (mended?) | 3 |

| Teeth marked (clenched) stems | 6 |

| Glazed fragments | 12 |

| Total number of fragments | 411 |

| Total weight | 628.6 grams |

Table 6.17 Attributes of Clay Tobacco Pipes.

Fragments from as many as 18 bowls, or just under half of the minimum number of pipes recovered, show evidence of decoration, not including plain makers' marks. The decorations include anchors, ships, line, leaf and geometric designs, although in most cases the size of the fragments made a more specific identification impossible. Only two stems were decorated, although six had manufacturer's names within rope borders.

Figure 6.31 Distribution of clay pipes by weight.

Table 6.18 Clay tobacco pipe marks (Oswald 1975).

The assemblage contains other features which clearly indicate modes of use. Breakage of the fragile stem lip, either being bitten through or snapped, appears to have been a common occurrence. Three stems have been sharpened, presumably for fitting to a new (possibly wooden) mouthpiece (Figure 6.30), although none of 99these replacement pieces was recovered and there is no clear sign of bindings on the stems. Six of the stem fragments have teeth marks where the broken stem has been clenched, often quite close to the bowl.

Figure 6.30 Clay pipes showing sharpening for refitting (top row) and teeth clench marks (bottom row).

Monetary

The only coin located during the excavation was the Chinese coin which has already been described above. Despite the absence of other 19th century coinage, rumours of buried money at Cheyne Beach were heard from several persons visiting the site during the excavation. This story appears to have been current since at least the 1950s, with a newspaper of that time reporting the popular belief that money (with which to pay the whalers) had been buried somewhere on the site for safe keeping (W.A. 17/5/1950).

In itself this discovery is quite interesting, both for the high value of the find, and the fact that if it really was made up of half crowns, the cache would have contained at least 168 coins. In some ways it is difficult to understand how such a significant sum could have been lost, particularly given its worth in the mid 19th century. No further information could be found on the fate of these coins.

Decorative - jewellery, hairpins, hatpins

Only two artefacts clearly fall within this category. The first is a carved piece of pearl shell (F0 spit 2) with a flower design which looks as if it were the head of a hairpin or hatpin. The other appears to be a finely carved piece of bone (C6 spit 3), possibly with a leaf design, although its original function has not been identified.

Figure 6.32 Pearl and bone decorative personal artefacts.

Other

Writing Materials

The most numerous artefacts associated with writing are the ten pieces of slate pencil, the majority of which seem to have been snapped during use. Seven of the ten have a utilised end, either sharpened or flattened through wear along one or more sides, with the longest segment (3.8 mm long) pointed at both ends. Most of the fragments are 3 cm or less in length. Four of the fragments of flat slate have chamfered or straight edges, such as would fit into the wooden edging of a slate writing board (Davies 2005). No markings were found on these pieces.

There are also two copper/brass artefacts which may come from writing implements. The first (from U99 spit 1) appears to be the base of a 'stub' style pen nib (Sears 1906) with the tines broken off. The second piece (X1 spit 2) may be the seat by which a nib is fitted onto the pen shaft, although if so, in this case it would have been a small nib. A single small piece of square pencil lead was recovered from U98 (spit 2).

Figure 6.33 Distribution of personal artefacts.

Penknives

The first example, from C5 (spit 2), is a badly corroded folding pen–knife, with the body length suggesting a blade size of approximately 5 cm. Strips of bone facing from both sides of the case were recovered from spits 2 and 3. A similar fragment of bone facing from a larger pocket–knife was found in U99 (spit 3), although there was no evidence of the knife itself.

100Miscellaneous

There are several further items which may well fall under the 'personal' category. The first is a threaded brass lock fitting with an opening for a small key (U99 spit 3). The second is a small flat brass hook (F0 spit 2). One or both of these may be associated with small personal storage boxes. No identification has yet been made for either the 9 cm long flat brass hook (F3 spit 5) or a small brass embossed fitting (F1 spit 3).

LABOUR

Whalecraft and Boating equipment

It was hoped that some indication of the industrial nature of the site might be located in the deposit. Ideally and perhaps a bit fancifully this would have been some specialised whalecraft item such as a harpoon or lance. However, this was not to be the case. The most relevant artefacts are boat–related hardware such as the copper sheathing tacks (described earlier) and a ring–bolt (17 cm/6.5" shaft with a 11.5 cm/4.5" ring) which was excavated from F2. A small sheet of copper, 14 cm by 25 cm with a number of nail holes through it, may also be associated with boat sheathing. The ring bolt is of a type normally fastened into mast or deck and used to fasten ropes or lashings (McCarthy 1983). Both the nails and the ring–bolt are associated with vessels larger than a whaleboat.

Despite some barrel hoop iron being excavated, its proximity to the house makes it likely that it was associated with food storage rather than the oil production of the station. However, as the re–assembly of oil storage casks in either 'barrel' (36 gallons/164 litres) or 'hogshead' (54 gallons/245 litres) size was vital to the functioning of the station, it is likely that a concentration of discarded hoop iron exists elsewhere on the site.

In the broadest terms, whale bones might also be construed as being indicative of the nature of the industry at the site, although as already discussed above it is best considered as a structural material. A single horseshoe found in A1 (spit 3) has been included in this category, although whether horses played some active role in the operation of the station or were simply present for transport purposes is unknown.

ABORIGINAL ARTEFACTS

Only one item has been identified as a probable Aboriginal artefact (X7 spit 3). This is simply a flake with a bulb of percussion, but no retouch. The fine–grained white material on which is based has not been firmly identified, although it is possibly chert. All the glass analysed was inspected for evidence of Aboriginal utilisation. Although some pieces had random flakes detached, there was no clear evidence of deliberate modification such as retouch or flaking from the bases of bottles (cf. Allen 1969; Allen and Jones 1980).

ARTEFACT DISTRIBUTION

The distribution and density of artefacts and the stratigraphic information from the excavations provides insight into the original topography of the site, the nature of the whaling era structures and activities, and the pattern of discard by the inhabitants. The different functional classes clearly have different distributions across the site.

The stratigraphic record from the excavated pits indicates that Structures One and Two were constructed on a low dune which sloped away to the south and east. Overall, the immediate doorway area outside Structure One and along the stone pathway contains relatively low densities of artefacts. However, this rises sharply after about four meters, with high densities of all classes of materials within squares T98, T99, U98 and U99, and to a lesser extent in T2. The four T and U squares are on the edge of the original dune and are therefore relatively shallow in depth. A similar pattern appears outside of Structure Two with low densities in B97 and C98, increasing in Z93 and C99. It is probable that in addition to being the area into which sweepings were pushed, the T and U squares also indicate the 'toss zone', that is the area into which larger items could be casually tossed from the doorway, beyond which a more deliberate discard effort would be required. This is akin to the 'Schlepp effect' in artefact discard distributions described by Schiffer (1977:20).

The north–eastern squares suggest a large, possibly seasonally damp inter–dune depression up to a meter deep. There is no reason to believe that the dense deposit of faunal material, discarded to the 'front' (north) of the probable kitchen (Structure Two), is not a continuous deposit throughout the area and for some distance beyond. The decreasing artefact densities in squares P99 and U87 may suggest an outer boundary to the discard zone, although in the former instance an unknown quantity of the upper part of the deposit may have been removed or disturbed. Despite a distance of nearly 12 m from either doorway, the artefact densities in U93 remain quite high, particularly in the bone and shell classes. It is probable that the disposal of material into the midden area required a more deliberate process, that is, the refuse would have had to be carried away from the building to be discarded into the depression. This distance presumably reduced smell and kept insects, rodent and larger scavengers away from the immediate doorways. There are some differences in the distributions of mammal and fish bones, with the latter increasing slightly at a distance from the buildings. Minimal amounts of bone were recovered from within the buildings. Shell appears to be focused slightly closer to the buildings.