CHAPTER 7

LIFE AT CHEYNE BEACH

The excavations at the Cheyne Beach whaling station were intended to address a variety of questions regarding the living and working conditions of the whalers and other persons living in this type of industrial maritime frontier community. The almost complete absence of historical description of life on the stations creates a particularly powerful ambiguity which could be approached only through exploration of the archaeological record. The original hope was that excavation would provide insights into how the whalers lived; the ways and conditions in which they were housed, and the diet and material culture of the labour force. If possible, the question of status difference within the workforce and other elements of social organisation within the frontier community could also be examined. A parallel aim was to examine the economies of the station for insights into trade and supply systems into these remote areas, as well as evidence of engagement with and adaptation to the environment.

As described in Chapters 5 and 6, the scope of the investigation narrowed into an intensive excavation of a single archaeologically rich part of the site, with the intention that this provide detailed insights. Interpretation of this material record is therefore made with reference to the known historical context of the whaling station and the development of European settlement within the Albany region and the known history of the Cheyne Beach station. In particular, it will be argued below that the excavated components of the site and the material remains within relate to the occupation of John Thomas, his wife and family.

THE ALBANY SETTLEMENT

Chapter Two has already described some aspects of the history of Western Australia, including the migration boom and bust, the difficulties in adapting agriculture and pastoralism to local conditions and the social and economic troubles which arose from these situations. Although the situation stabilised during the 1840s with a slow re–commencement of immigration and industry (including whaling), the population remained small and short of capital. New agricultural and pastoral settlements spread along the lower west coast harbours and inland across the Darling Ranges, assisted in part by the improvement of land routes resulting from the 1850s introduction of convict labour. New outposts were also established to the north of the Swan River, opening frontiers for miners, pastoralists, pearlers and whalers. Even into the 1860s and 1870s the colony remained focused on primary production, rather than development of manufacturing industries.

European settlement and population growth along the south coast proceeded at an even slower. Considered part of the Swan River colony, the harbour town of Albany had been established several years earlier in 1826 as a military outpost and penal settlement. In March 1831 it was officially handed over to the new Western Australian administration and declared a free settlement, but for many years was to remain a marginal and often moribund frontier village. As well as sharing most of the woes of Perth's early crises, Albany's distance from the administrative centers on the west coast and consequent delays in communication further exacerbated problems. Contemporary writers observed that by sail from Fremantle it took a week or ten days just in rounding Capes Naturaliste and Leeuwin (Burton 1954:37). The overland route proved to be an equally long and arduous trek of twelve days or more and it was not until 1872 that a telegraph link was finally created between the two communities (Glover 1979; Garden 1977). Despite King George Sound being a superior harbour, it was in the interests of the Perth administration to keep Fremantle as the focus of trade.

Contemporary descriptions of the Albany settlement are disparaging.

The population of the Sound is approximately 200 or 250 persons. It is really surprising how they continue to live, as there appears to be scarcely any trade or means of support. The settlers are chiefly employed in hunting the kangaroo, for the sake of that animal's skin. The settlers depend chiefly, not upon agriculture, but upon the sale of kangaroo skins, whale oil, and the other sales and barterings effected during the occasional visits of the few American whalers that call at the Sound for wood and water (PG 10/2/1849).

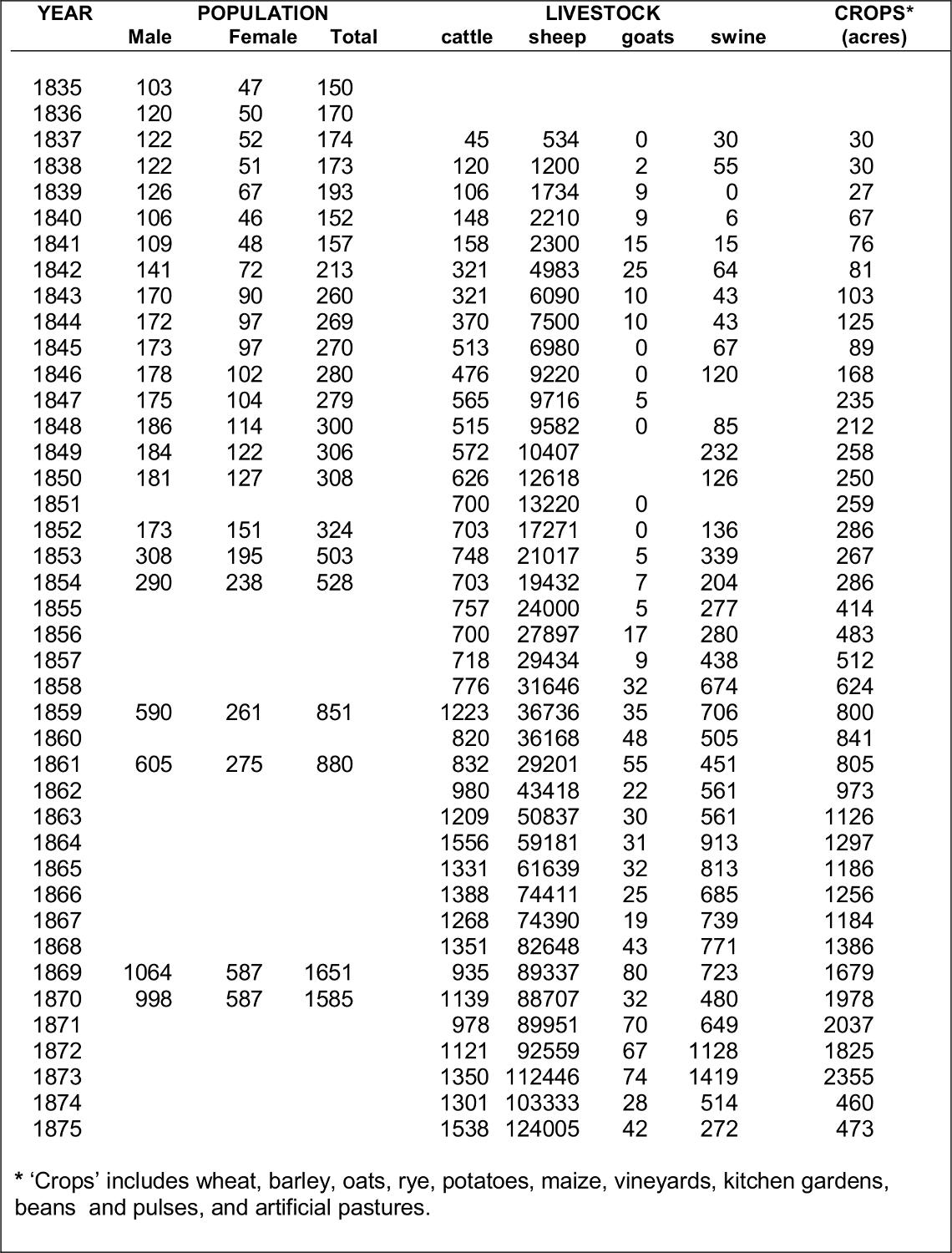

While possibly exaggerating, these comments do contain an element of truth. Blue Book statistics show the population remained under 300 persons for over 20 years and, despite some gaps in the colonial records, does not appear to have passed 1500 persons for another 15 years after this (Table 7.2). Between 1852 and 1880 Albany rose to prominence when it was selected over Fremantle as the Peninsular and Oriental (P&O) Steam Navigation Company's coaling depot. During this time it became the regular port–of–call for steamers, received the mails from England and was the main contact point between Western Australia and the rest of the world. The construction of a jetty and facilities, as well as the permanent employment of over 30 people at the P&O depot and offices (Bulbeck 1969), were also important stimulators to the local economy. However, aside from 103these monthly diversions, the tone of the settlement often remained depressed until later in the 19th century.

CHEYNE BEACH

The establishment of a whaling station at Cheyne Beach followed the familiar pattern of choosing an anchorage already frequented by American whalers. The 1846 season was a partnership between John Craigie, Solomon Cook and John Thomas. In the following year this association had dissolved, with the party run by Thomas as owner, manager and chief headsman. Cheyne Beach operated as a two boat fishery with a crew of 12 to 14 men under Thomas’s control until 1868 or 1869. Details of the industrial history are presented in Appendix A. From 1870 to 1877 the station was used by a variety of shore parties, although it is possible that for some of this time it was actually Thomas's party under different management. John Thomas was therefore associated with the Cheyne Beach whaling station for at least 22 years of the 31 year period during which the location was used, and can be seen as a major influence on the formation of the archaeological record of the site. Unfortunately, the historical record of Thomas and life at Cheyne Beach is scant and confused.

The Western Australian Dictionary of Biography suggests that John (or James) Thomas was born in 1818 and arrived in Western Australia with his parents in 1829 (Erikson 1988:3039). It also states that in early 1835 he was sentenced to seven years transportation to Tasmania for participating in the plundering of the schooner Cumberland after it was wrecked approximately 30 km south of Fremantle. Contemporary court records contradict this, reporting that John Thomas (junior) received only six months hard labour (CSO 37/86, 12/1/1835), with some suggestion that he did not actually leave Western Australia. This is unfortunate for our story, as a Tasmanian connection would have provided a convenient explanation for his whaling skills. However, Cheyne Beach whaler Capt. John Sale's (1936) memoirs also suggest that the John Thomas of Cheyne Beach was of Tasmanian origin. With several persons in Western Australia bearing the same name, we can only be sure we are following the career of the correct man from 1846 and his first involvement at Cheyne Beach.

In 1851 John Thomas attempted to purchase the Cheyne Beach station site, but was refused because it would have included the anchorage area. His second attempt to obtain this property came in April of 1855, when the Government negotiated with Thomas to purchase his Albany town lot which was required for the expansion of the neighbouring Convict Depot. Thomas offered to swap this land for 10 acres at Cheyne Beach, later reducing this to a request for only four acres. The government appears to have made a counter–deal, offering instead a remission of £10 on the (unstated) purchase price of this land (Surveyor General 1354:226, 30/4/1855). Thomas must have accepted these terms as soon afterwards he was also granted an eight year tillage lease for Bald Island (Surveyor General 1430:242, 5/9/1855). Curiously, a study of title and lease records for both the Kent and Plantagenet districts failed to provide any supporting evidence for either Thomas's ownership of the town lot, or for a subsequent purchase or lease of either the Cheyne Beach or Bald Island areas.

The few documents which mention John Thomas provide little real information about the man. The later memoirs of McKail (1927) and Sale (1936) appear to afford him a level of respect as the recognised leader of Albany's whaling community. In addition, he is known to have trained or employed key identities such as Thomas Sherratt, John Cowden, Nehemiah Fisher, Hugh McKenzie and Cuthbert McKenzie, all of whom would later form their own whaling parties and become key identities in the last phase of shore whaling.

Thomas is referred to in most accounts as 'Captain Thomas' (McKail 1927; Sale 1936; Erikson 1988:3039), while on a petition of 1855 he signed himself as "Whaling Master" (CSR 338/60: 3/7/1855). It is possible that outside of the whaling season Thomas was involved with the coastal trade, with an 1855 document referring to him as the owner of a schooner (CSR 338/23: 20/3/1855). In 1871 he was also listed as a boat owner (Erikson 1988) although the craft was unnamed. Sale (1936) claims that Thomas salvaged material from the Arpenture which wrecked opposite the Cheyne Beach whaling station in 1849 and employed a Mr. Metcalf (possibly the American deserter known to have worked at nearby Cape Riche (Erikson 1988:2151) to build a small vessel called the Mary Ann. The registration of this vessel has not yet been confirmed.

Perhaps the most significant pieces of anecdotal information concern John Thomas' personal life. He was married to Fanny Davis and had three daughters, Mary Ann (born 1849), Fanny Sophia (born 1850), and Katherine Ellen (birth date unknown, but known to have been the youngest child) (Erikson 1988; McKail 1927). Sale (1936) notes that

Mr. Thomas continued to work at Cheyne Beach where he brought up his family of three, and all married at Albany to become Mrs. Geak, Mrs. John Cowden, and Mrs. George Broomhall.

This brief statement introduces two significant factors into the consideration of the occupation of Cheyne Beach. The first is that Thomas's wife and small children lived at the whaling station, possibly for a period of years. As will be argued below, the archaeological data provide strong support for the excavated structures and artefacts being associated with the household of this small family unit, rather than the seasonal labour force.

The second factor emerging from Sale's memoir is the possibility that John Thomas and family lived at Cheyne Beach throughout the year, rather than just 104during the whaling season. In an 1854 court action by Thomas he also describes himself as living ‘at Cheyne’s Beach, 30 miles from Albany, where I carry on a whaling station’ (PG 24 March 1854). In May of 1855 there is a report that Thomas and three others had been swept out to sea for several days on Thomas's schooner while en route to Cheyne Beach (CSR 338/23: 20/3/1855; Inq 4/4/1855; Inq 18/4/1855). Even allowing several weeks for pre–season preparation, this would be nearly two months earlier than might be expected if the station was only used for whaling purposes.

As described above, tracing Thomas's land ownership has proved difficult. Even prior to selling his town lot to the Government sometime after April 1855, there is no clear evidence for him living in Albany.

Having noted the historical evidence suggesting that the Cheyne Beach whaling station was not a purely male–inhabited seasonal camp, it then becomes necessary to consider a range of other factors. These include effects upon the social organisation of the camp, the nature of the site and buildings, as well as possible variations within other aspects of the material culture. Even greater differences might be expected if Thomas and his family did maintain a year–round occupation of Cheyne Beach throughout some or all of the 22 years or more of his involvement with the station. In this latter case, the possibility of a more permanent use of the site did not arise until late in the analysis, and therefore was not specifically tested. The implications of these various scenarios will be investigated as part of the interpretation of the archaeological evidence, provided below.

INTERPRETATION OF THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL EVIDENCE

Some years after the original research for this volume was completed a brief account was found of an 1889 visit to Cheyne Beach, just over a decade after the abandonment of the whaling station. The anonymous traveller records an overland trip from Albany to the ‘fishery reserve’, describing the bleached bones of whales scattered on the shores of the bay and the ‘ruins of a number of stone huts’.

The walls are composed of stones or whalebone cut into blocks and used as large bricks. Invariably these bone bricks have been used as flooring. The stone used for walls seems to be a soft sandstone nature, red and yellow. The fishing settlement must have looked very bright and picturesque in the days of its existence as a fishery (Albany Mail 18/12/1889).

The writer also notes the remains of flower gardens at the front of ‘the cottage’, a freshwater well situated behind the site, and that the station look–out had been posted on the high rock on the adjacent hill.

The description of Cheyne Beach correlates with some aspects of the archaeology, but also raises ambiguities. As described in Chapters 5 and 6, the surviving stonework associated with Structure One appears unlikely to have supported full height walls. The stones are roughly laid, unmortared and often comprise of only a row of large boulders, suggesting low retaining walls to allow the floors to be levelled rather than foundations. The single wooden post found in–situ in the southeast corner also suggests a wooden framed wall. Of course, the 1889 description does not eliminate the possibility that the station originally had a mixture of stone and wooden buildings. Insufficient of Structure Two was excavated to be certain of its construction. Whalebone flooring is certainly evident in the archaeological record for both buildings, while several fragments of whalebone trimmed into blocks or bricks were also found.

The overall size and nature of Structure One is comparable to the standard domestic cottage plan commonly seen throughout much of 19th and early 20th century Western Australia (Oldham 1968; White 1979). Iron and copper nails were found across the site, although it is impossible to determine if these might have come from walls or roofs. The 1870 census which includes the first attempt to document the building stock of the colony, provides little insight into the latter, noting that of the houses ‘of less than four rooms’ in the Albany/Plantagenet district, 68 were shingled, 69 were thatched, and four roofed in iron or slate (Knight 1870:40). The distribution of flat glass is suggestive of windows in the area of squares C7 and V6, roughly equally positioned along the western side of Structure One. There was no clear evidence for a beach side (front) door, other than a possible path surface, although only a few squares were excavated along the western wall.

Although there is no physical evidence of an internal division in Structure One, this is not particularly surprising given the apparent absence of post–holes or footings trenches for several of the external walls and the damage from the 1987 trenching. The almost complete lack of structural hardware and furnishings also makes interpretation of internal areas difficult and there is no clear evidence for internal walls. If the structure functioned as barracks for the men, their needs might have been best served by a single large room. If it was John Thomas’ residence an internal wall may have been a more appropriate, particularly as his three daughters may well have lived there until their late teens (Erikson 1988). The 2 x 3 m addition to the southeast corner may have formed an additional sleeping/storage area. Further evidence supporting Structure One as Thomas’ residence is provided below.

The limited excavation of Structure Two means little can be said, although it is possible that this was an external kitchen connected to the main cottage by the stone flagged pathway. The proximity of this structure to what appears to substantial amounts of dietary refuse, discarded into what were originally natural depressions 105around its edge, also supports this sort of usage.

There is no doubt that the station would have included the same variety of industrial and domestic structures common to other whaling stations, and the 1889 description certainly makes it clear that there were several buildings on the site. The only other historical reference to another structure is a rare anecdotal account of life at the station which incidentally describes one of the whalers walking to ‘the cookhouse’ to ask the station cook for cups of tea and cakes for the men (McKail 1927). Presumably the men slept in a separate barracks or several cottages. Elements of this description might fit with Structures One and Two as barracks and cookhouse, although as will be argued below the artefact evidence suggests these were associated with the Thomas family.

Where the living structures and cookhouse for the whalers were situated is uncertain. However, based on the topography of the site and especially the low–lying swampy ground to the south of Structure One, it is very likely that these were to the north and northwest of the excavated areas. If Structure One was the home of the Thomas family, there may have been some separation between the areas. Regardless, this would place the workers’ buildings within the area of the current car park; although there is a possibility they may have been in the fore dune area immediately west of Structure One.

Excavation within the car park was not permitted and it is probable that any structural remains would have been graded away, although deeper deposits may exist below the fill such as seen in pits P98 and P93. A test pit (TP1) dug approximately 30 m north of Structure Two along the northern edge of the car park on a small sandy ridge at the base of the slope contained artefacts (sheathing nails, transfer print ceramics, bone fragments) comparable to the excavated areas to a depth of 10 cm. This ridge stands more than a meter higher than the adjacent car park level and provides further support for extensive grading and destruction of deposits. Several small test pits in the dunes north of Structure One, as well as close inspection of vehicle access tracks cut through to the beach, failed to recover evidence of further structures or significant artefact deposits.

In the late 19th–early 20th century a wool store was constructed at Cheyne Beach by the Hassell family, allowing wool from hinterland farms to be gathered close to the harbour awaiting shipment (C. Westerberg pers. comm. 1992). Although no historical evidence survives on the nature of the building, which was situated in the area of the current car park, a wool store of similar age which survives at Cape Riche, the next closest harbour, is constructed of stone. It is therefore possible that the stone from the buildings of the Cheyne Beach whaling station were salvaged for foundations or walls of the wool store.

There is even less evidence for the location of industrial buildings such as tryworks, whalecraft and oil storage, or boat sheds. As described in Chapter 4 there is a flat area on the southwest edge of the point, immediately above a granite sheet leading down to a deep scour channel. Although close to the end of the point, the ridge of the headland still provides some shelter from the worst of the weather. An eroding surface on this flat area shows a layer of ash, rusted iron flakes and some 19th century artefacts. Excavation was not possible, although this may be a reasonable position for a tryworks. Once barrelled the oil could have been rolled to a storage area closer to the beach. The beach area to the front and north of Structure One continues to be ideal for small boat launching and anchorage.

Domestic Life

Tablewares

In the first instance it is the nature, diversity and context of the Cheyne Beach tablewares, mainly in the form of ceramic fragments, that indicate Structure One and the associated refuse deposits are unlikely to have been associated with the all–male seasonal labour force. Despite the complexities of consumer behaviour making simple correlations between ceramic values and status problematic (Klein 1991; Crook 2005; Wurst 2006), tablewares are arguably still the main archaeological markers of economic level and social affiliation available to us. The simplest understanding is that households with high income and upper social status will have more and better ceramics than low socio–economic households. It might be expected that the isolated situation and the heavy usage likely to result from feeding a dozen or more men would necessitate the use of cheaper and sturdier creamware tablewares, or metal tablewares. However, the ceramics recovered are of the expensive transfer–printed earthenwares, generating a high CC index value, with attention apparently paid to creating near–matching sets of shell–edged and willow pattern. There is also the use of handled tea cups with matching saucers and other service forms such as tureens, unlikely to be of concern to a male industrial labour force in a frontier situation, although as discussed in Chapter 8 this may be another assumption that should be challenged.

The second level of interpretation is the symbolic nature of the ceramic assemblage, suggesting that selection and purchase is gender based (i.e. women have greater control of the domestic domain into which ceramics fall) and that changes in the nature of ceramics can be linked to changes in domestic modes and rituals. If we follow Yentsch (1991) in perceiving ceramic selection as a female domain, we might envisage Fanny Thomas having insisted upon maintaining the symbols of status and the significance of domestic ritual despite distance, isolation and other prevailing social conditions. Given the limited precision in dating the use of the ceramics, it is possible that some these were slightly out–of–style and cheaply purchased items (Lawrence 2006:111). Non–ceramic tablewares such as 106the goblet base, tumblers and decanter provide further support for maintenance of desired domestic patterns. This is discussed further in the concluding chapter.

The historical record gives no specific indication of the socio–economic level of John Thomas and family. However, Thomas’ ownership of the whaling station, property and a vessel, plus the eventual marriage of his daughters to middle echelon public servants, the Albany Harbour Master and Post Master (Erikson 1988), are suggestive of the equivalent of at least middle class status or higher within the settlement. Remaining conscious of and performing current fashion would have been of some importance in maintaining that status.

Finally, the tablewares can be used to inform on access to markets, with an implication that more remote communities will have limited access to consumer goods and a reduced choice, which will potentially also be of lower quality. It is also assumed that the time lag between factory production and local purchase will be significantly greater for more isolated households. Cheyne Beach is a decidedly 'frontier' situation, at the site of an isolated outpost of an isolated settlement of the British Empire at the extreme far end of the trade network. The role of the ceramics in understanding the trade systems in operation during the early settlement period will be discussed further below.

Beyond the tablewares, the preparation and storage categories are under–represented. As stated earlier, no preparation wares such as pots or pans or associated implements such as knives were recovered. Given between 20 and 30 years of occupation of the site, more cutlery and non–flatware tableware items might have been expected. Although it is possible that a separate kitchen was located elsewhere on the site, the large quantities of faunal material still suggests that Structure Two was a food preparation area, or that one was nearby. It is possible that the under–representation of these other wares is a function of the excavation strategy, and that further sampling to the south of Structure Two, adjacent to TP3, might yield relevant items.

Personal

While many of the individual artefacts within the Personal category could easily be used by the male workers at the station, collectively the assemblage lends weight to the picture of a family maintaining particular social and domestic standards. The harmonica, clay tobacco pipes, and penknife are most likely to fall within the domain of John Thomas, rather than the female members of the family. Similarly, there are items which are closely associated with the female members of the household, including the pearl shell hairpin, the small comb and decorative carved bone piece. The sewing activities represented by the many pins, thimbles and glass beads are part of a female domestic and leisure realm. The dice, gaming board pieces, and marbles can be linked with the toy tea set to create an image of the family’s, and especially the children, amusements. Conversely, the fragments of slate writing tablets and pencils indicate that their schooling, probably through Fanny Thomas, remained important (c.f. Davies 2005).

Clothing

Despite a variety of metal, bone, glass and shell buttons and the several metal buckles recovered from Cheyne Beach, most are of plain types not described or discussed by collectors and have limited diagnostic value (e.g. Epstein and Safro 1991; Whittemore 1992). It seems that most of the bone buttons and the one–piece and two–piece stamped brass and composite buttons are cheap, mass produced items (Cameron 1985).

Many of the fastenings are associated with utilitarian work clothing, including pants, trousers or overalls of canvas or leather (Cameron 1985:20; Birmingham 1992). This is consistent with what might be expected from John Thomas’ roles as whaler and sailor. Although there are no specific descriptions of the forms of clothing used by the whalers, one could suppose that it would have been similar to that used by fishermen. During the mid–19th century this would have comprised canvas trousers, possibly with woollen leg warmers, an oiled smock or knitted wool guernsey, oiled leather boots, and an oiled or tarred hat (Levitt 1986; de Marly 1986). In heavy weather a mackintosh might be worn, although the traditional heavy oilskins remained the most commonly used protection (Levitt 1986). There could of course be variations, such as oiled bib–and–brace overalls or dungarees, sometimes with all–in–one boots (Williams–Mitchell 1982). The freezing winds and sudden squalls of the southern coast would require boatmen to wear warm and waterproof gear. Many of the above clothing items would require buttons, presumably of the common types recovered from the excavations.

The two possible naval buttons are interesting but may have come to the site through a variety of processes. Rather than speculate on Thomas’ maritime connections or the possibility of a visiting naval vessel, the most parsimonious explanation is simply that they came as slops or clothing traded from a passing ship.

A proportion of the buttons can potentially be ascribed to the presence of women (and children) at the site, although care needs to be taken. It is possible that some of the smaller shell and glass buttons may have been clearly associated with women's clothing, although the most diagnostic items in this case are the metal hooks and eyes which were used to fasten items such as bodices (Sichel 1978).

Although alcohol bottles were found across the site, they are in remarkable low numbers, given that many almost certainly post–date the whaling period (Table 7.1). It has already been suggested that the shortage of storage items probably reflects the use of casks as bulk containers, in addition to which glass bottles may also have been considered a scarce resource to be curated and recycled. Alternatively, Thomas and his wife may 107have been temperate drinkers. The presence of a woman and several children might also have moderated the drinking behaviour of the other men at the station.

| Container type | Minimum no. |

|---|---|

| ALCOHOL | |

| Bitters (brown) | 1 |

| Gin (square black) | 5 |

| Beer/ale (cylinder black) | 5 |

| Wine (circular green) | 11 |

| CONDIMENTS | |

| Pickles | 9 |

| Sauce and herbs | 2 |

| MEDICINAL | |

| Medicine/toiletry | 15 |

| Ointment | 10 |

Table 7.1 Summary of Glass and Ceramic Containers

The assortment of patent medicine containers is similar to many urban and rural 19th century sites with limited access to medical care or more potent medications (e.g. Davies 2001). Albany was at least 50 km distant from Cheyne Beach by boat and it is possible that at times there was no qualified medical practitioner available at the settlement to assist in any case. Consequently, it is likely that all but the most severe ailments would have been treated at the station.

The interpretation that the deposits from which the patent medicine bottles were recovered are associated with the Thomas family, including Fanny Thomas and several young children, suggests a range of possible ailments and medical concerns beyond what might be expected in a male industrial workforce. However, the fragmentation of the bottles makes it difficult to identify specific treatments.

Diet

While it was felt that diet may have been the area in which adaptation to local conditions and resources would be most evident, this proved to not be the case. The Cheyne Beach faunal assemblage shows that, despite the whaling station's isolation, the diet of the inhabitants of Structure One was dominated by introduced species.

In particular, sheep bones greatly outnumber those of pig or cattle. While this may have been a function of personal taste or preference, historical data on stock numbers in the Albany/Plantagenet region suggests it may simply have been a matter of availability. The summary of Blue Book and census data presented in Table 7.2 shows that throughout the study period sheep were by far the most numerous and successful of the livestock and therefore the cheapest of the available domestic meats. Although focused on the 1830s period, Gardos’ documentary analysis and excavations at the Old Farm Strawberry Hill in Albany recovered a similar pattern of utilisation of sheep as the major source of meat (Gardos 2004:52–54).

Blue Books indicate that in 1845 a sheep cost 8s. while a cow cost £10, although Cameron (1981) states that prices could vary wildly as settlers either tried to conserve their stock for breeding, or sold them to solve liquidity problems. Accounts of Albany during the 1840s and 1850s repeatedly describe the shortage of meat in the settlement (Burton 1954; Hassell n.d. a.). One memoir (Hassell n.d. a.) recalls that in the late 1850s beef was only available once a month and that even then this consisted only of the surplus from what was required by the regular P&O steamer. Most other times only mutton was available.

Another important indication of the state of food supply comes from a memorial of July 1855, signed by most of the adult European male residents of Albany and the surrounding region (including John Thomas), pleading with the government to lift the heavy harbour fees which were discouraging ships from visiting.

We are deserted by the steamers and apparently by all other vessels, our stock of flour is exhausted, and many parties are now suffering great privation in consequence, and the prospects of the place are alarming (CSR 118/60: 3/7/1855).

This situation contradicts some of the historical claims that Albany's income was largely derived from supplying whaleships with fresh produce and meat. It may indicate distortions in the economy and agricultural practices of the region (e.g. a focus on livestock rather than agricultural production) which might have resulted in the dire shortage of certain essential foodstuffs. However, Garden (1977) also describes at some length the apparently lethargic attitude of many of the early Albany residents towards performing public works or even towards producing sufficient food.

Given the high representation of all skeletal elements of sheep at Cheyne Beach, it appears probable that animals were brought in live and slaughtered as necessary. Keeping meat on the hoof would have negated many of the difficulties of storage, even with the cold winter climate of the southern coast during the whaling season. A further advantage of sheep over cattle was ease of transport, as it is considerably easier to convey a live sheep, particularly in small boats. A small flock could also have been kept at the station for immediate needs.

It is possible that the tillage lease of Bald Island allowed John Thomas to run his sheep there without the need for pens or shepherds, a practice which continued during the late 19th and early 20th centuries (WA 17/5/1950; C. Westerberg pers. comm.). It would also have protected the flock from Aboriginal hunters.

With the evidence for exploitation of larger native fauna limited to a single macropod tooth, quokka appears to be the only regularly hunted terrestrial animal. Given their small size and limited meat content, 108Quokka must have provided occasional variety, rather than a staple dietary item. While there may have been a mainland quokka population in the immediate vicinity of Cheyne Beach during the early settlement period, it appears likely that the animals consumed at the whaling station were taken from Bald Island. A possible scenario is that the whalers snared or chased down the small marsupials while visiting the island to round up sheep. If this was the case, their exploitation should be seen as harvesting of a captive resource, rather than hunting.

Another possible scenario for the quokka and seal remains is that sealers were still resident on Bald Island during the early occupation of the whaling station and that these animals formed part of a trade relationship between the two groups. William Nairn–Clarke’s report on sealing activity along the south coast during the early 1840s stated that Bald Island was frequently occupied by sealers on account of the "wallabees" on it.

One of the sealers, named 'Gemble' or familiarly 'Bob Gemble', originally from Van Diemen’s Land, used to reside there with his black gins and his children for months together, and for aught that I know may still be there, or somewhere in the Archipelago, to this day. This man seals on his own account and his wives perform the part of a boat's crew (Nairn–Clarke 1842).

There is no documentary evidence to confirm that Gemble or other sealers were still present on Bald Island during the mid–1840s, contemporary with the Cheyne Beach whalers. It is probable that after Thomas was granted the lease of the island in 1855 these groups, if they were still active in the region, would have been prevented from camping there.

The relatively small proportion (by weight) of bird bones suggests that these also provided variety rather than a major component of the diet. While chicken is present in small quantities, the majority of the bone is from native species which might also have been collected on occasional forays to Bald Island. It is probable that the quantity of bird bone has been affected by post–depositional attrition, such as scavenging, described below.

Firearm artefacts in the form of percussion caps might be associated with foodways, especially the possibility of hunting. However, as percussion caps were detonated at the site of firing it seems incongruous that so many discharged examples were located in and around the station buildings. As hunting from the back door of the station appears implausible (except for possibly shooting at birds), the caps might be associated with post–whaling occupation of the buildings by fishing and hunting parties. Other evidence of this sort of casual use includes the high concentration of nails around the fireplace which is suggestive of the burning of old structural timbers or shingles, as well as smashed ‘black’ beer bottle in same area.

Dolphins, seals and sharks would have been regularly encountered during the course of whaling activities and may well have been slaughtered on an opportunistic basis, using the harpoons, lances and other implements normally carried in the whaleboats. The possibility of supply from sealers has also been mentioned above. The fish, crab and shellfish species recovered from the excavations reflect collection from the beach and reef within the immediate vicinity of the station. Despite the large quantities of fishbone recovered, no evidence was found of fishhooks or other procurement items, suggesting netting or lines were stored elsewhere.

One of the major unknowns in the diet of the whaling station is the consumption of whale meat. Whale meat, blubber, brain and some internal organs are certainly edible and are still valued foods for several cultures (Cousteau and Paccelet 1988). As described in Chapter Two, Aboriginal groups considered whale meat and blubber preferred foods and spent the whaling season close to the shore stations. However, whale meat is reputed to have a strong taste which does not necessarily appeal to the Western European palate. While pelagic whalers were known to eat whale meat on occasion and Mawer (1999:171) reproduces several recipes, it was neither a preferred or regular part of the diet (Shoemaker 2005). The same is likely to have been true for Cheyne Beach.

Archaeologically it is difficult to detect consumption of whale meat, blubber, or other body parts. Because of the size of the animals, meat could easily be carved off without cutting bone which would ultimately end up in a archaeological context. In the case of Cheyne Beach, whale bones were scattered over many areas of the site, particularly in close proximity to the buildings, although this is almost certainly from its structural use rather than as dietary discard.

Although the Cheyne Beach site offers good preservation, other taphonomic factors need to be considered, in particular the potential impact of dogs, dingoes and other scavengers. Walters' (1984) study of bone attrition from around a modern campsite is especially relevant given the midden–style disposal pattern not unlike that proposed for Cheyne Beach. Walters recorded the number of butchered bones of several taxa (including kangaroo, sheep, goanna and chicken) disposed of over a six month period and the levels of recovery of each type at the end of that period. In summary, the small animal bones suffered drastic reductions in number, with only 1–2% later recovered from the site, while the larger animal bones provided a recovery of between 9–14%. Dogs were identified as the primary scavengers, although rats, crows and goannas also contributed.

While there is no specific evidence that domesticated dogs were kept at Cheyne Beach their presence is not unlikely, while dingoes were still being reported in the immediate area as late as the mid–1960s (Storr 1965). With a substantial midden of animal bones plus whale carcasses beached in the shallows, the site must have presented a very attractive focus for 109scavengers. Piper's (1990) consideration of taphonomic factors on historic sites suggests that removal and reduction of bones by canines, pigs and other animals can be identified by the presence of gnawing marks. No such evidence was detected on any of the Cheyne Beach bones, although scavenged bones may have been removed beyond the site periphery (cf. Walters 1984).

If we follow Walters' (1984) study, it is probable that a high proportion of the smaller bone content of the midden, including quokka, fish and bird bones, has been removed or destroyed.

The larger bones (primarily sheep and pig) would also have been reduced in number, although the sheer mass of material discarded in the midden would guarantee a higher level of survival. A further influence on scavenging activity may well have been the (potential) seasonal occupation and abandonment of all or part of the site, influencing scavenger access to the midden.

Table 7.2 Albany District Population, Agricultural and Stock returns (Blue Books 1835–1875 & Census reports).

110The non–faunal faunal component of the whaler's diet would have included flour, potatoes and other vegetables. Considering the number of men to be fed, the largest proportion of this would have to have been brought into the site, probably from Albany. However, it is probable, particularly given the presence of Fanny Thomas and children, that there would also have been a small cottage garden to grow at least some fresh produce. The 1889 description of the station describes the ground near the fishery being 'covered in clovers and grasses, doubtless the result of the whalers' cultivation' (Albany Mail 18/12/1889). Cheyne Beach farmer Charles Westerberg related that a son of one of the Cheyne Beach whalers whom he had met at the site had indicated that the ‘vegetable patch’ had been in the low area to the southeast of the site. No landscape or floral evidence was found in this area, nor were there any agricultural implements located during the excavation. No large seeds were recovered from the excavations. Palynological study might be possible, although the alkaline conditions of the site are not conducive to preservation.

The glass bottles included at least 11 which contained pickles, sauces and other condiments including vinegar. Condiments such as pickles and sauces were common methods of flavouring food. On the frontier they could also make stored or unfamiliar foods more palatable. Heavy fragmentation means the real count is likely to be much higher, with the same problems of curation and recycling as for the other glass vessels.

The analysis of the faunal material provides the most significant insight into the relationship between the inhabitants of Cheyne Beach and the surrounding environment. In many respects the diet at Cheyne Beach was maritime or marine in nature, with little evidence of intrusion into the hinterland behind the station for the purpose of hunting. Even the sheep and quokka would appear to have been captive populations on Bald Island, accessible only by boat and waiting to be harvested when necessary. With an eight year lease of the island, Thomas could have simply left his stock for long periods of time. Similarly, the more obvious marine resources are all readily accessible along or very near the shores of Cheyne Beach itself. The emphasis on these resources may well indicate both a reluctance and limited need to move beyond the immediate coastal zone. The whalers lived the season in almost constant readiness for the hunt, which would have been interrupted by excursions away from the coast. It is worth noting that the Cheyne Beach crew registrations always included a cook, which is also reported in anecdotal accounts (McKail 1927).

As there is strong evidence that Structures One and Two and the adjacent midden deposits are associated with the Thomas family, the question arises whether their diet was the same as the workers. Undoubtedly they suffered similar constraints of supply and availability, although their diet is unlikely to have been identical to that of the whalers. Similarly, Fanny Thomas is likely to have prepared the food for herself and her family in her own kitchen, separate to the cook. Consequently, while the Cheyne Beach faunal material provides an insight into supply and diet preference on the maritime frontier, it does not allow us to make any statements regarding the diet of the whaling workforce itself.

There are few historical indications of the foods consumed by whalers at other Western Australian stations and there are few comparable analyses of non whaling sites. The Carnac station equipment lists various items, including 100 bushels of wheat, 10 lbs of pepper, 10 gallons of vinegar, 1.5 cwt (168 lbs) of sugar, one bag of rice, two casks of beef, two casks of salt pork, one ton of salt and one chest of tea (see Table 3.2). Furthermore, there was fishing equipment including a seine, 24 fishing lines and 20 shark hooks, clearly indicating the intention to exploit marine resources. Seymour's diary from Castle Rock frequently mentions the slaughter of cattle ('bullocs') for the station (Seymour n.d.). This diary also suggests that headsmen were given preferred meat cuts.

Thomas Sherratt’s 1835–36 accounts ledger includes purchases associated with his 1836 Doubtful Island Bay whaling operation. Although it is difficult to be certain that these large quantities of food were solely for the whalers and not for his other stores and enterprises, the ledger includes nearly purchases of 2500 lbs weight of flour, over 250 lbs (and possibly as much as 550 lbs) of sugar, 160 lbs of biscuit, 672 lbs of beef and 418 lbs of pork (including 2 casks of beef and 1 of pork), 48 lbs of tea, almost 50 gallons of spirits, 17 gallons of rum, 4 pounds of pepper, as well as 4 dozen hooks and 8 fishing lines (Sherratt 1836). The remoteness of Doubtful Island Bay compared to Carnac and even Castle Rock’s proximity to other settlements presumably meant that supplies for almost the whole season were required.

Curiously, sheep are not mentioned in any of these sources. Does this indicate that whalers expected beef rather than mutton, and that if excavations had been elsewhere a different faunal assemblage would have been obtained? Lawrence’s work with the extensive documentary records for James Kelly’s Tasmanian whaling operations, including crew agreements, indicate that whalers could be supplied mutton or beef depending on availability (Lawrence 2006:106). Presumably at Cheyne Beach mutton was more available.

Import Patterns and Local Manufacture

The bulk of consumer items arriving in Western Australia arrived through the normal process of local merchants being supplied from Britain. In terms of Cheyne Beach's position on the formal trade network, it should be considered that between 1852 and 1880 Albany's position as the P. & O. coaling port put it into regular direct contact with the trade route from Britain. 111This presumes that the steamers would carry at least some cargo for the colony, other than the mail. If so, despite Albany's marginal status as a settlement, at times its access to the centers of production (in Britain) would have been comparable or possibly even better than that of the larger colonies of the west coast. Many of the Western Australian colonists maintained their links with relatives and friends in Britain, ordering specific items (sometimes requesting the ‘latest fashions’) directly through them or having standing annual orders via agents, to be sent out each year (e.g. Shann 1926; Hasluck 1955). New fashions in clothing, ceramics or other items could therefore have arrived from London within months of their debut. Consequently, the time–lag on the maritime would potentially be a matter of months, rather than years (c.f. Klein 1991).

The mean dates for the Cheyne Beach ceramics (particularly the shell–edged wares) are suggestive of a lag time, that is, they tend to date to the first half of the period of occupation. This may be a function of curation rather than a product of the trade networks, or purchase of cheaper, out–of–date ceramic styles and patterns. Apart from several slightly mismatched transfer prints, there is no evidence for Cheyne Beach or the colonies being a dumping ground for inferior goods or ‘seconds’.

By the late 1860s the combined imports from other British colonies (Victoria, New South Wales, South Australia, Mauritius and Singapore) were rapidly approaching levels equal to those from Britain (Knight 1870). It is not possible to determine if this included colonial manufactured items, although the majority was most likely to have been re–exported items from Britain which would have added further delay to their arrival.

An unknown quantity of material also entered through the 'grey market' of American whalers. The whalers were willing (and preferred) to engage in barter with smaller settlements in return for meat, fresh produce and other supplies, including oil (Gibbs 2000). However, it is not possible to identify this component of the trade and supply within the archaeological record. In one respect the isolation of Cheyne Beach, particularly if it was occupied year–round, would have made it a possible contact point for American ships wishing to shelter or water in the bay. However, the antipathy between colonial and foreign whalers, and Thomas's previous objections to an American presence in the area (CSR 189/254: 23/8/1849, and see Appendix A) suggest that direct contacts may have been limited. Despite this, it is possible that Thomas might still have received American materials indirectly through George Cheyne's private supply depot at nearby Cape Riche, or through any of the other Albany merchants.

With the exception of several small and probably home–made artefacts in the 'personal' class, the Cheyne Beach assemblage provides no evidence for colonial production of consumer items. The Blue Books, census reports and other documentary sources suggest that besides primary producers there were only a limited number of manufacturers, mostly associated with garments (including a number of tailors and shoemakers) or various forms of carpentry. In 1870 there was only one nail maker listed and several gunsmiths, and the latter probably did not manufacture new firearms (Knight 1870). Although there were numbers of brickmakers, no potters or potteries are reported. In Albany in 1870 most of the male population registered was involved in pastoral and agricultural pursuits.

Aboriginal Contact

In many respects it is not surprising that the evidence for an Aboriginal presence at the site is extremely limited. First, the historical evidence suggests that the Aboriginal workers at the station were well integrated with their non–Aboriginal colleagues. They were presumably housed in the same barracks, or if not, were housed nearby. They were supplied with food, had access to steel knives and other manufactured items, and so had no need for recourse to flaked glass or stone. It is possible that, as at other stations, Cheyne Beach was regularly visited by large groups of Aboriginal people intent on feasting on the whale carcasses. Their camp, which has not been located but was probably at some point away from the main station, may contain flaked stone or glass tools or other evidence.

CONCLUSIONS

There is strong evidence to suggest that while the structures and artefact deposits excavated at Cheyne Beach were part of the whaling station, they were associated with the household of the manager, his wife and their three daughters, rather than with either the domestic or industrial activities of the whalers proper. For this reason the main questions based on investigating the operation and lifeways of a whaling station, focused on the nature of the industrial workforce, remain unresolved. However, the Cheyne Beach assemblage provides in many instances a range of far more interesting insights into the wider themes surrounding colonial adaptation, subsistence and supply on the maritime frontier.

The faunal evidence suggests a conservative diet based on mutton and less frequently beef and pork. The sheep were probably brought to the station live and may have been allowed to run free on Bald Island until needed. The pigs may also have been brought live, although the limited quantities and cuts of cattle bones would suggest the beef was probably a salted meat (i.e. brought in pre–butchered). There is little evidence for adaptation of diet or practices to take advantage of the native terrestrial fauna, although a variety of marine fauna was exploited. The emphasis on marine resources rather than terrestrial hunting may be interpreted as an attempt to minimise absences by those who procured the fauna from the immediate coast.

112Despite a relatively isolated position at the end of the trade network, the consumer items, particularly the ceramics, are of an expensive kind, suggesting attention to status and domestic rituals was being maintained. The occupants of the buildings were still clearly dependent upon imports from Britain for most manufactured consumer goods, with little or no evidence for local industry beyond building materials and small personal and recreational items.

Although it is possible that women and children were present on other whaling stations, Cheyne Beach is probably the exceptional case resulting from the continuous association with the same manager/owner for over two decades. The only comparable situation of extended occupation, at Castle Rock, has no historical evidence of a family being present (Seymour n.d.). It can be expected that other parts of the site contain archaeological evidence of the industrial processes and the domestic arrangements for the crews. However, it is possible that the presence of women and children may have subtly influenced many of the behaviour patterns of the men, particularly in areas such as the consumption of alcohol.