CHAPTER 2

HISTORY OF SHORE WHALING IN WESTERN AUSTRALIA

The factors that encouraged the British colonies in Australasia to pursue whaling were clearly embedded in social and economic circumstances of the 18th and 19th century (Pearson 1983). The massive changes in technology and demography that formed the industrial revolution had resulted in a vastly expanded market for whale oil, primarily as a lighting fuel in fluid and wax (candle) form, and as a high quality lubricant for machines and precision instruments. In addition, whale oil and waxes were required for a variety of other manufacturing processes such as wool and fiber cloth production, leather treatment and manufacture of toilet soaps and perfumes (Chamberlain 1988). The flexible baleen from the mouths of humpback and right whales had a variety of uses in the manufacture of clothing, furniture and a diversity of other items including springs and umbrella ribs (Cousteau and Paccalet 1986).

The dynamic expansion of whaling through the later part of the 18th century had initially seen French, British, American (and to a lesser extent Dutch and German) pelagic whaling fleets competing in the Atlantic. During the last quarter of the 18th century the British whalers were able to gain supremacy, in the first instance through the crippling of the American whaling fleet as part of the English offensive during the revolution of 1775. This was followed by the 1784 passing of an Act by the British Parliament that placed a massive £18 per tun duty on foreign oil entering England, effectively closing off American access to what was then the major market (Mawer 1999:44). Finally, American whalers and vessels were being encouraged to desert to British ports such as Milford Haven or the French port of Dunkirk.

As a result of this virtual monopoly the British whaling fleet was able to expand rapidly during the late 18th century, although the flourishing international market for sperm oil was such that the Americans were still able to find markets and rebuild their fleet. However, the increasingly over–fished Atlantic waters forced attention towards untried regions and in 1789 the British whaler Emilia became the first vessel to round Cape Horn and test the Pacific whaling grounds. As this ship returned with its full cargo of oil, news of the potential of the new grounds was hastily transmitted throughout the industry. This heralded a boom period of several decades, with British, French but particularly American whaling fleets rapidly spreading through the Pacific and Indian oceans (Churchward 1949; Colwell 1969; Mawer 1999).

The origins of whaling in Australasian waters and the development of a colonial industry has already been discussed in some detail by other writers (Morton 1982; Chamberlain 1988) and need only be summarised briefly here. Initial British efforts to penetrate the new whaling grounds were severely hampered by the existing trade monopolies on the Indian and Pacific Oceans, held by the East India Company and to a lesser extent the South Sea Company. These prevented access to the region and curtailed early plans to establish a new southern fishery based in the Australasian colonies. Various concessions and relaxations were made over time to allow whalers into these areas, although it was not until 1819 that all restrictions were lifted (Morton 1982: 121). By this time the American fleet was well established in the Pacific, while the British fleet was edging towards its decline.

Surrounded by the successes of the pelagic whaling fleets and the flourishing oil market, the administrators and major capitalists of the Australasian colonies quickly came to view whaling as a potential staple industry that would provide a lucrative product for export. By 1805 the first shore station had been established in the Derwent River in Tasmania, while a number of vessels based in or visiting Australia had begun operations in adjacent seas (Nash 2003). The possibility of a colonial whaling industry independent of and in competition with the British fishery produced a strong reaction in England. In an unsuccessful attempt to control or curtail this development, the British government in 1809 imposed severe duties on colonial oil imported to Britain. Colonial produce attracted duties of approximately 29 times higher for sperm oil and 16 times higher for black (right and humpback whale) oil as for that from English whalers (Morton 1982:121). These duties remained in place until 1823, when a change in policy abolished the excise.

The growth of Australasian whaling therefore really dates from the mid–1820s, encouraged by the removal of the tariffs on colonial oil, the withdrawal of the British whalers from the Pacific and the growing domestic market (Chamberlain 1988). Close proximity to the resource meant that operating costs were reduced compared to UK–based whalers, increasing the profit margin and assisting in the development of pelagic, bay and shore whaling ventures. Shore whaling parties from Sydney and Hobart soon spread along the coasts of eastern Australia and Tasmania and across the Tasman Sea to New Zealand.

The scale of the shore whaling industry in each area varied from two boat fisheries to as many as 11 boats or more at some New Zealand stations (Morton 1982:228). In some instances shore whaling comprised 'only one strand of a diverse land–based interest' for settlers and was combined with grazing, timber–getting and other maritime interests (Pearson 1985:5). Until as late as 1834 whale products provided the major export income for New South Wales, although by 1850 wool, timber and coal production had increased to the point where the 11fishery contributed only one percent of total earnings (Little 1969).

In virtually all regions the shore whaling industry appears to have peaked in the late 1830s, followed by a rapid decline during the 1840s. The closure of many Australasian shore stations in the late 1840s has not been clearly explained, although in part it has been linked with a decline in whale stocks and resulting fall in production (Pearson 1985; Campbell 1992). With agricultural, pastoral and other interests now well established, investors' capital could be directed towards more profitable ventures, including pelagic whaling. The economic depression during that decade created further financial difficulties for station owners, resulting in either abandonment or re–organisation on a more modest scale (Little 1969). Shore whaling continued in various parts of eastern Australia and New Zealand on a greatly reduced scale for several more decades, with a handful of stations and individuals operating sporadically even into the 20th century. By 1910 modern forms of shore whaling with powered chase boats, explosive harpoons and large–scale processing infrastructure had almost completely replaced the older, open boat forms of the industry.

PRE–SETTLEMENT (1616–1826)

Faced with a buoyant oil market and successes in other parts of Australasia, it is surprising that it took so long for the Western Australian colonists to engage in whaling. However, while not independent of developments in the rest of Australasia, the whaling industry that emerged was neither closely related to or the product of the pelagic or shore whalers of either Tasmania or New South Wales.

Since the early 17th century a succession of Dutch, French and English commercial and exploratory vessels had observed the western Australian coast, reporting scientific curiosities but finding little of potential commercial value. The exception was that in almost all cases comment was made on the number of whales seen. When British explorer George Vancouver arrived in King George Sound in September of 1791 in the midst of the whale season, he noted that 'The little trouble these animals took to avoid us, indicated their not being accustomed to… visitors' (Vancouver 1984: 353). Only five months later, in April of 1792, the whalers Asia and Alliance of Nantucket made an exploratory visit to Shark Bay, although being in the wrong season for either humpback or right whales the vessels quickly departed northward. In the three years since Emilia's successful voyage into the Pacific the spread of the American whaling fleet had been swift, often preceding government sponsored explorations. Between August and December of 1800 the British whalers Elligood and Kingston also cruised the western Australian coast, but with more success (Richards 1991).

In the opening years of the 19th century a new series of intensive French and British explorations of the Australian coasts began, all making frequent sightings of whales. French Captain Nicolas Baudin suggested in his published journals that if whaling vessels were to visit the west coast in the right period, they would ‘…obtain their cargo very promptly and successfully' (Cornell 1974:512). In particular Baudin was attracted to Shark Bay, which had been a focal point of their investigations and offered a protected anchorage for vessels, stating:

This place would be worth settling, if one considered it a suitable area for whaling; the only commercial activity on this coast presenting advantages that should not be overlooked. I am convinced that the Dutch had their reasons for not giving us a more accurate plan of it than the one on their charts (Cornell 1974:512).

In February of 1803, Baudin's vessels encountered the American sealing ship Union in the harbour now known as Two People Bay. The sealer was visiting the area on the strength of the information in Vancouver's published journal, hoping to obtain a full cargo of skins before proceeding to China. In the following year at least one other American sealer visited King George Sound (Fanning 1924), suggesting that private interests were effectively utilising the information about the Australian coast generated by the official expeditions, in addition to amassing intelligence through their own explorations and other sources. By 1818 when the French and British dispatched the Freycinet and King expeditions respectively there was clear evidence of increasing European activity along the south and west coasts, quite probably related to whaling and sealing (Marchant 1982). When Dumont d'Urville visited King George Sound in October 1826, sealing parties from the eastern Australian colonies were clearly well established on the offshore islands of the south coast (Lockyer 1826).

EARLY SETTLEMENT (1826–1842)

In December 1826 a small detachment of soldiers and convicts under the command of Major Edmund Lockyer arrived at King George Sound on the south coast to establish a military outpost known as Fredrickstown and later Albany. Its purpose was partially to forestall any remaining French colonial ambitions, but also to determine the suitability of the area for a new penal colony (Garden 1977). Lockyer was directed to investigate and report on the natural assets of the area, making his own observations about the immediate vicinity but also interviewing the several gangs of eastern Australian sealers already living and operating in and about King George Sound. The sealers claimed to have hunted on the islands of the southwest coast from as early as 1820 and had penetrated as far north as the Swan River. As well as describing rivers, islands and natural 12features, the sealers also recalled encounters with Aboriginal groups (HRA III (6):490, 2/4/1827).

Based on these interviews, Lockyer reported to Governor Darling his concern that unless sealing was regulated almost immediately, a valuable resource would be 'irreparably injured if nor destroyed altogether' (HRA III (6):471, 22/1/1827). He suggested the Government lay claim to the coastal islands, prohibit private sealing and farm the seal populations every three years, while placing restrictions upon activities during the breeding season. Lockyer extended this note of urgency to the large numbers of sperm whales in the adjacent waters, although he recorded that the sealers said these were as yet unexploited because 'the whale ships' (of unstated origin) would not approach too close for fear of the coast (HRA III (6):490, 2/4/1827). However, his reports were largely ignored, with Governor Darling stating in a letter to Earl Bathurst that he had 'in fact given no attention to the subject, being without means of carrying into effect any measures which might be deemed expedient to adopt' (HRA I (13):273, 3/5/1827).

In 1829 a new British settlement was established at the Swan River on the west coast, based on the 1827 reports by a young naval officer named James Stirling. In contrast to earlier explorers who had disparaged the potential of a west coast colony, Stirling extolled the virtues of the region, arguing that its position in relation to the prevailing winds meant that military and naval forces stationed there could be easily dispatched to either the eastern Australian colonies or India (Statham–Drew 2003). He also suggested that the location was ideal for China traders to call in for refreshments before proceeding northwards. As the Chinese were generally not interested in European goods, Stirling proposed that the normally light outward cargoes of British vessels could be supplemented with articles to supply the Swan River Colony. Once there they could obtain refreshments and ship a new full cargo of local produce such as timber, trepang, sealskins and whale oil, which were of greater interest to the Asian merchants (HRA III (6): 585, 20/7/1828).

The motivations behind Stirling's enthusiasm for a new colony have been the subject of some discussion, with the point raised that his uncle happened to be a director of the East India Company which still controlled British trade in the Indian Ocean (Cameron 1975, 1981; Appleyard and Manford 1979). In summarising the main advantages of the proposed settlement, Stirling recognised the potential for a whale and seal fishery, although it was simply one of a large number of possible industries suggested as a means making the submission more attractive (HRA III (6): 577, 18/4/1827). His main thrust was that this was an extremely fertile region ideally suited for an agricultural settlement and that he should be given the role of Governor of the new colony.

Although the Colonial Office initially rejected his proposals, Stirling personally petitioned for support upon his return to England. A timely change in government administration placed several sympathisers for the scheme in senior positions, with further encouragement possibly provided by renewed French and American activity in the area (Cameron 1978).

The key was to be land apportionment based upon capital investment. For every £3 worth of equipment which could be used to improve land or was applicable to farm production, the settler would be entitled to a grant of 40 acres (16.2 hectares). Cash did not entitle a settler to land, although as a means of inducing settlers to provide their own labourers, any servants and their families brought over were given a value, resulting in an indenture system. Stirling was also allowed to head the settlement, being given the title of Lt. Governor.

Although there was initially an unprecedented enthusiasm for the new settlement, several factors soon emerged which immediately endangered the colony's existence. First was that the rush of arrivals completely overwhelming the planned processes of exploration, land division and apportionment. This situation was exacerbated by the realization that the fertile area had been grossly over–estimated, in reality being limited to narrow strips along the rivers. Many of the arrivals lacked suitable skills for colonising and had over–invested in agricultural equipment as a means of maximising their land grant. They had often chosen inadequate or inappropriate gear, sometimes based on poor or incorrect advice. Insufficient food supplies and the difficult conditions in the tent settlement at Fremantle caused many settlers to continue on to the eastern colonies or immediately return to England to spread their tales of woe. When news of this state of affairs filtered back to England emigration rapidly slowed and then halted, leaving the Swan River Colony with a black reputation for many years to come (Cameron 1978).

For the settlers who remained the first several years were marked by poor crop yields and high stock losses as they experimented with the unfamiliar seasons and conditions. Their early over–expenditure on capital purchases had left them with limited cash reserves, making it difficult to import further equipment or diversify their activities away from agricultural production.

Among the settlers were also persons originally from eastern Australia who had established small service and trading enterprises at the Swan River Colony. Their departure removed much of the liquid capital, leaving the settlement in a precarious economic position that would last for the better part of a decade (Statham 1981a).

Faced with a range of other difficulties, it is not surprising that Stirling's initial attitude towards fostering a whale fishery was relatively cautious. In a despatch to the Colonial Secretary in January 1830, only six months after settlement, he reported as follows.

The facilities which are offered for carrying on a whale fishery have not escaped the attention of some of the settlers even this early. I have had applications from several parties but judging the time not arrived I have not hastened by particular encouragement such establishments. It is believed 13that there is an abundance of fish to make such a fishery possible and the coast is visited between the months of May and November by a multitude of whales; it will be my object to foster these fisheries and boats and small vessels drawing their maintenance from these shores (cited in Heppingstone 1966:30).

Over the next several years there were numerous proposals, prospectuses and submissions to establish whaling parties, most requesting government support (e.g. CSR 10/62, 18/11/1830; SRP 18/27, 7/8/1832; SRP 6/95, 24/12/1830; PG 23/3/1833; PG 5/11/1834). In many instances Stirling offered various kinds of assistance including land grants or leases, while colonists recorded in their diaries and letters their hopes that eventually one of these ventures would be successful, as it would 'be a chief means of giving stability to the colony' (Moore 1884a:167). However, all of these schemes failed, mostly from being unable to raise the capital to purchase the necessary equipment.

In August 1833 the Perth Gazette noted large numbers of whales along the coast adjacent to Fremantle, bemoaning the lack of equipment to pursue and capture them (PG 17/8/1833). Despite this, in the same issue there was a report of a five–week old whale calf being caught by two men fishing between Carnac and Garden Islands. The blubber, which they flensed off at Carnac Island, was taken back to Fremantle and tryed out to give 45 gallons (170 L) of oil (PG 17/8/1833). The following week's issue also recorded that a whale had been thrown ashore at North Fremantle, with the finder trying out over 100 gallons (378 L) of oil (PG 24/8/1833).

By the end of 1833 the initial economic crisis in the Swan River colony had passed and in her analysis of the early economy of the settlement Statham (1980) has identified the years between 1834 and 1837 as a period of consolidation. The settlement became self–sufficient in basic foodstuffs, the first products of the pastoral industry were exported and immigration recommenced on a small scale. There was also limited development of the non–rural sector, mainly based upon military and public works contracts, although some small industries such as boat building were also established (Ewers 1971).

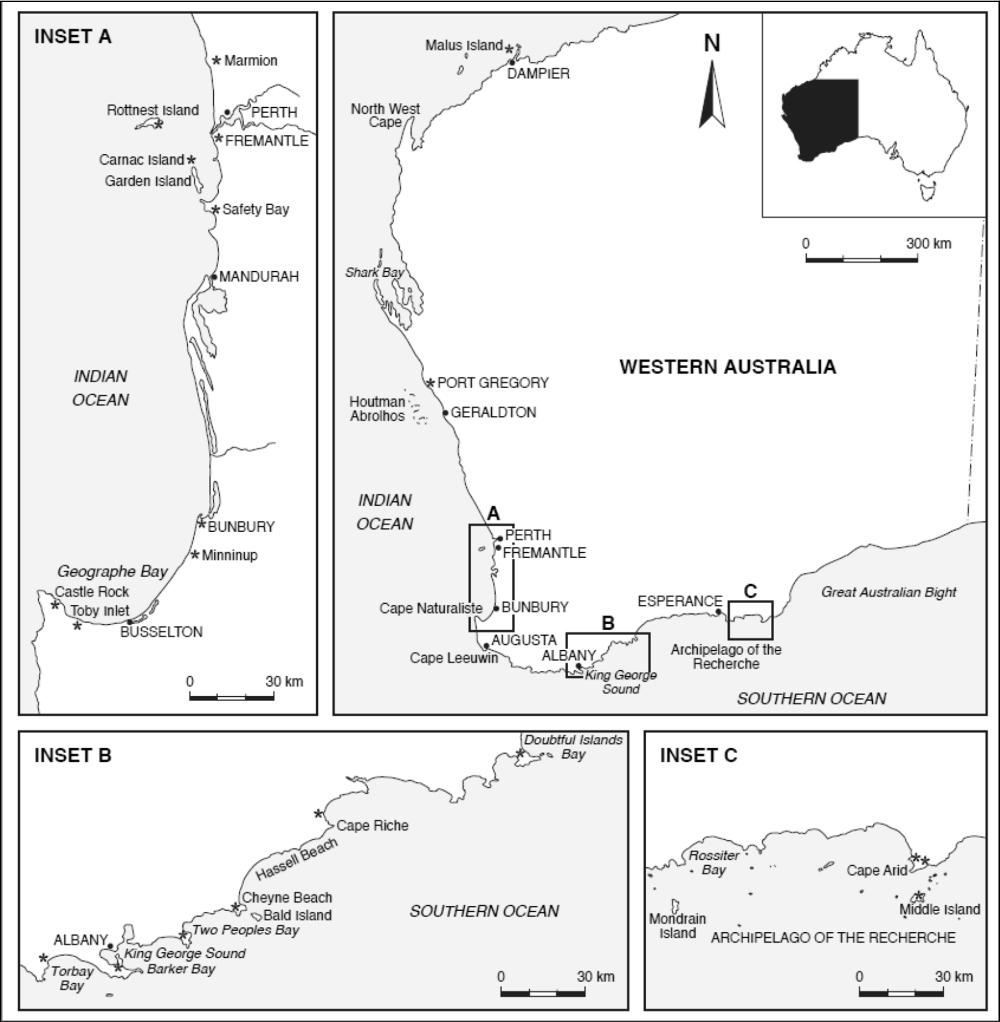

Figure 2.1 Main settlements and shore whaling stations. (Drawing – Wei Ming)

14While most local transactions were still undertaken through a barter system, a cash economy was finally starting to emerge and small reserves of liquid capital were accumulating (Statham 1981a). Many of the workers in the colony remained indentured as servants to the major settlers, although a labour market had begun to develop where free men could sell their services for relatively high wages, especially in contract seasonal labour.

In addition to the increased range of economic activity, official and private explorations once again began to range through the southwest, examining the potential for pastoral and agricultural settlement (Jarvis 1979). Administrative responsibility for the King George Sound outpost was transferred to Swan River and the southern settlement began a slow expansion as a free colony (Garden 1977). The general impression is one of growing confidence amongst settlers and government that the colony would finally prove to be viable.

Colonial attentions were also turning towards finding resources with export potential. The booming oil market and the successes of the other Australasian colonies clearly made whaling an attractive proposition in both official and private eyes. The Perth Gazette, generally considered the mouthpiece of the Government, ran a series of articles presenting whaling as an easily pursued and remunerative industry (PG 24/8/1833; PG 3/5/1834; PG 13/8/1836). Exploration parties reported sightings of large numbers of whales along the southwest coast and as far north as Shark Bay (PG 8/11/1834; PG 16/7/1836; PG 3/9/1836; SRG 29/12/36). A report on the potential for a fishery at the Swan River estimated that from 10–40 whales were sighted annually between the mainland, Rottnest Island and Garden Islands, and that if a look–out was kept at least five times that many would be seen (PG 16/7/1836).

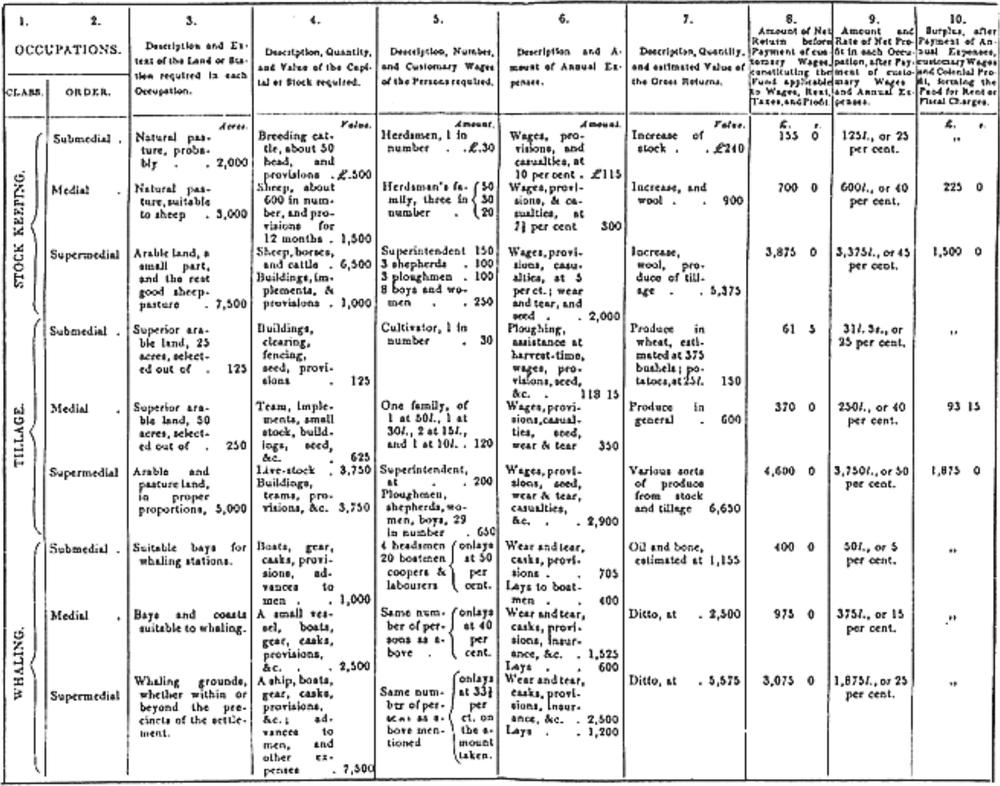

Despite being surrounded by this bounty, whaling still required specialised equipment that had to be made or imported and paid for. Although Blainey (1966:111) states that in eastern Australia a whaling station could be established 'for a mere £300', a situation which may have been true of Western Australia a decade later, in this initial phase there were neither local manufacturing industries nor an existing body of cheap or second–hand whalecraft which could be drawn upon. Governor Stirling estimated that capital of £1000 would be necessary to establish a four boat shore fishery, with a further £1105 for annual costs (1837a:260; Figure 2.4). Morton's (1982:225) research suggests that even this figure may have been optimistic and that £1500 to £2000 in capital would have been required.

Although the colonial economy was now stable, this did not mean that it was affluent. Promotional pamphlets distributed in England during this period described the prospects for a whale fishery at some length (Irwin 1835; Anon 1836), starting again the long and ultimately unsuccessful attempt to attract investors or new colonists with an ambition to go whaling.

Several further local efforts were made towards forming whaling companies, most of which either failed to become established (PG 7/5/1836; PG 3/9/1836; CSR 46/20), or had to be modified into less capital intensive activities such as sealing (PG 8/11/1836). The exception was in May 1836 when Thomas Booker Sherratt, an Albany merchant, informed the Colonial Secretary that he and William Lovett of Van Diemen’s Land were preparing a whaling party at King George Sound (PG 7/5/1836; Garden 1978:64). A later set of reminiscences state that Lovett arrived from Hobart Town in 1835 in the barque Jess 'with extensive whaling equipment' to join Sherratt and Mr. Dring of Perth in whaling and sealing about Albany (Keyser 1929). Sherratt’s ledger (Sherratt 1836) records the name of John W. Lovitt, presumably a member of the well known Tasmania maritime family who owned several whaling vessels during this period (Lawson 1949). If so, this is the only known instance of eastern Australian investment in a Western Australian whaling party. From Sherratt’s ledger it appears that the partnership provided Sherratt with equipment, experience and additional capital to overcome the prohibitive establishment costs.

Although nothing more is mentioned through the year, a late report confirmed that a fishery had been formed and even achieved a moderate success.

The whaling party… is on a small scale… 15 whales were struck during last season and 7 were taken, but whether from the insufficiency of means or the want of experience on the part of those employed remains to be determined, not more than 15 tons of oil and about 2 tons of whalebone were obtained. (PG 24/12/1836)

It would appear that this station was located in Doubtful Island Bay, 160km north–east of Albany (SDUR S3/271: 6/12/1836). From the perspective of later whaling operations, the catch by this first station was average, although the yield of oil was remarkably low. The export return of the 13 tuns of oil was reported as £520, with the total value of whalebone and sealskins cleared through the port listed as £630 (BB 1836).

By 1837 the economic environment of the Western Australian colonies had improved to the extent that the settlers had accumulated sufficient capital to make several major developments possible. The first of these was the establishment of the Bank of Western Australia, presenting many colonists with their first opportunity for making short–term loans with which to buy stock and equipment or attempt new ventures (Ogle 1839). The second was a growing import market that, together with the rise in exports, resulted in the expansion of businesses, fortunes and influence of merchants resident in the colony (Statham 1981a). The third was the establishment of two whaling companies at Fremantle, financed through a broad joint–stock investment involving a number of the major settlers and merchants in the Swan River colony.

15In contrast with most of the whaling parties subsequently formed, both of these companies were based on a relatively elaborate formal investment structure. The Fremantle Whaling Company, whose station was on Bathers Beach in Fremantle, had an initial capital of £400 from shares of £20 each (SRG 11/5/1837). It was later necessary to raise a further £300 with a release of £10 shares (PG 19/8/1837). The Northern Whaling Company based on Carnac Island (also referred to as the Carnac or Perth Whaling Company) operated with capital of £600, raised from shares of £10 each (SRG 4/5/1837). Further details of the companies and their main investors are provided in reports from the Swan River Guardian (SRG 4/5/1837; SRG 11/5/1837), while Statham (1980; 1981a) has discussed their financial structures in some detail. The history of the 1837 season has already been described on a number of occasions (Kimberley 1897; Battye 1912; Heppingstone 1966; Statham 1980; Statham–Drew 2003) and will only be briefly reviewed.

The establishment and operation of the two Fremantle whaling parties became closely associated with the various political factions and disputes within the colony. The Fremantle Company in particular benefited from two major public works performed on their grant using prison labour; the construction of a stone jetty and the quarrying of a tunnel through the adjacent hillside to simplify access from Bathers Beach. In addition, each group attempted to gain advantage through dealings with the several American whaling vessels that put into Fremantle during the year. Daniel Scott, a major investor in the Fremantle Company, was accused of using his position as Harbour Master to purchase whaling equipment from the American whaler Cambrian to the exclusion of the Northern Company (SRG 16/3/1837). On the other hand, the Northern Company convinced several crew members from the same vessel to join their party (PG 15/4/1837). When formed, both parties were comprised of three boats, totalling about 20 men per station.

The 1837 season was characterised by an obvious lack of skill in both of the whaling parties, severe damage or loss of equipment and a disastrously high loss of life, totalling seven dead and several other serious injuries by the end of the season. Although it is probable that the headsmen and boat steerers had some prior experience, most of the boat hands were inexperienced boys aged 21 years or less (PG 8/7/1837). The fishing did not proceed as successfully as predicted, with the two parties frequently competing but often forced to cooperate to achieve any result at all. By August it was decided to unite the two stations for the remainder of the season, with operations ceasing in mid–October (PG 19/8/1837; PG 14/10/1837).

Parallel developments were occurring on the south coast in 1837, with two whaling stations established at Doubtful Island Bay (Wolfe 2003). Information on these parties, remote from the settlement and the eyes of newspaper correspondents is sparse. Thomas Booker Sherratt continued his partnership with William Lovett (CSR 53/45: 14/4/1837), while George Cheyne, another Albany merchant, also decided to enter the industry (Garden 1977). During the early stages of the season, Sherratt wrote a series of letters complaining of the presence of American whaling vessels along the south coast (CSR 55/14: 5/5/1837). Although initially appealing to the captain of a visiting British man–of–war to drive the foreigners off the coast (CSR 53/43: 14/4/1837), Sherratt was quickly pacified by entering into a relationship with the master of the American whaler Charles Wright (CSR 55/29, 9/8/1837). The terms of this situation were partly reported in a letter to the Swan River Guardian:

we are to have all of the bone of the whales caught by us. For the first 30 tuns of oil, Captain Coffin to have [one quarter]. After 30 tuns one half. We are to have no other troubles with whales but catch them. Captain Coffin to cooper all our casks for £5. Captain C to have the oil after the last 30, at a fixed price. These are better terms than the first we offered to join upon. (SRG 29/6/1837).

There are no other details of the nature of the agreement, particularly whether any other equipment or assistance was provided. Cheyne had also formed an association with an American vessel, although details are similarly obscure. From indirect evidence, it appears that Cheyne's whaling crew actually embarked on the foreign vessel and joined with the American crew in bay whaling operations, receiving a share of the catch at a fixed rate (CSR 55/29: 9/8/1837).

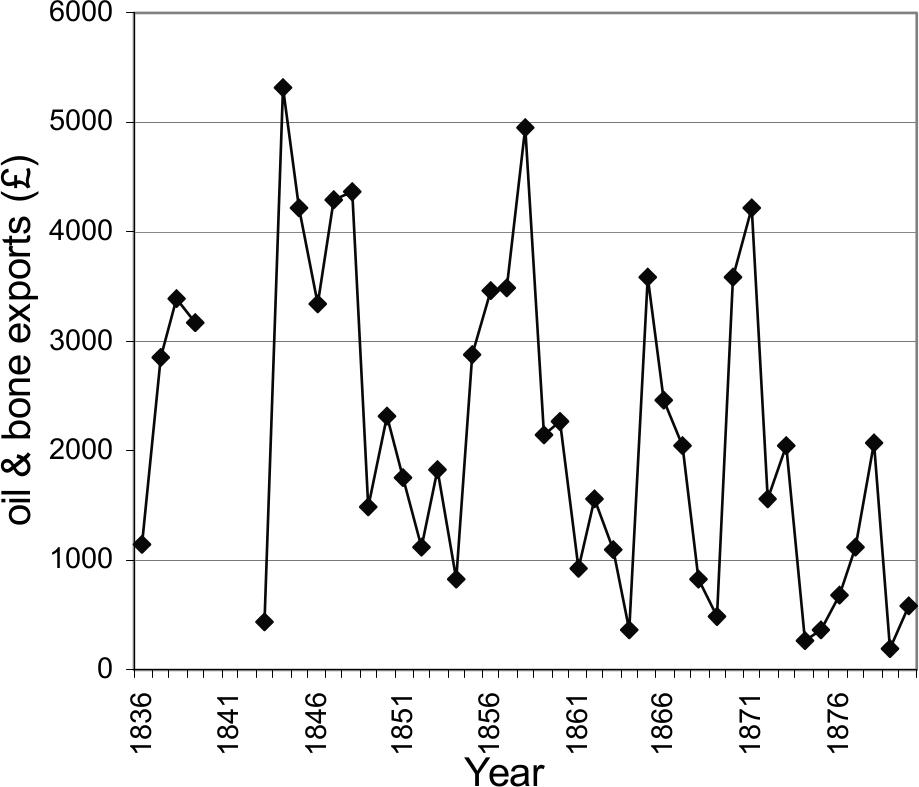

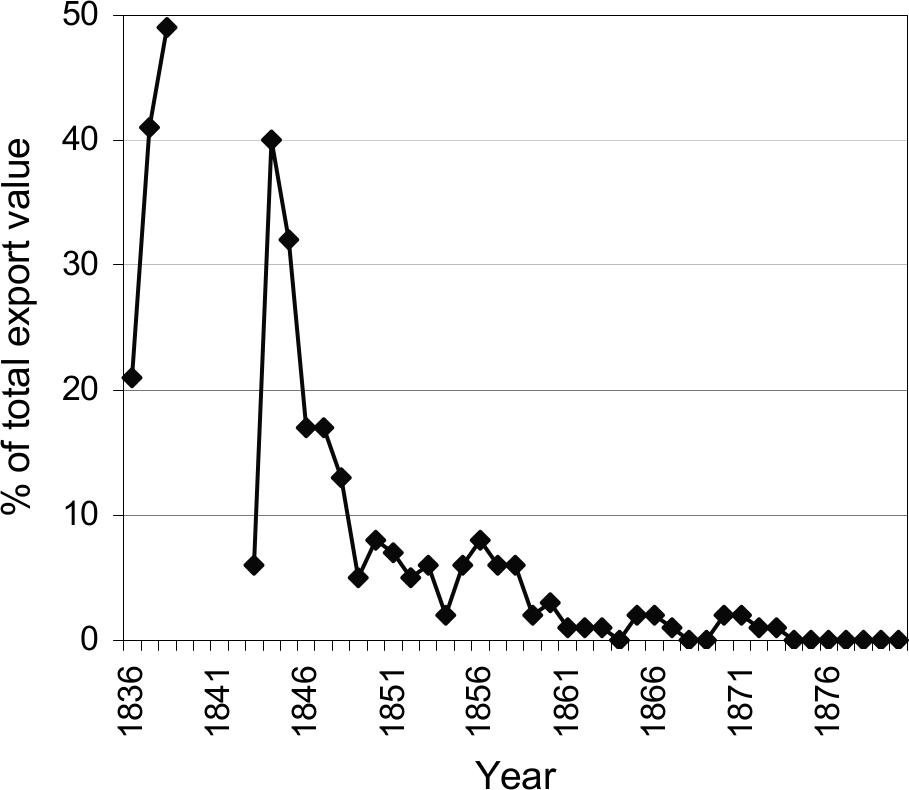

Although the total catch record and gross value of the 1837 season's production is not recorded, the combined result of the west coast stations saw the export of 71 tuns of oil worth £1420 and 4.5 tons of whale bone worth £360. From the south coast the export amounted to £900 worth of oil and £180 worth of bone (BB 1837). This was a far cry from the 250 to 300 tuns of oil per station confidently estimated earlier in the season (SRG 29/6/1837), and still lower than the estimated value of £4200 that had been suggested at a later point in the year (Stirling 1837a). However, in the context of the Western Australian economy the £2860 of whale products immediately formed the state's major export; exceeding the previous year's total export of £2700 and bringing the 1837 total to £6906 (Figure 2.2, Figure 2.3).

Aside from an increase in export earnings, the economic and social consequences of the foundation of the whaling industry were felt throughout the colony. The contracts and orders to supply the stations with food and equipment, as well as to construct buildings and other works, further helped to stimulate local economic growth and development. It is, however, significant that the principal investors in both the south and west coast parties were merchants or persons with strong maritime interests (SRG 4/5/1837; SRG 11/5/1837). By supplying capital with which to establish whaling operations, these individuals could expect returns not only from the sale of oil, but also from receiving preference in servicing the needs of the parties. The controlling influence and 16involvement of merchant groups was to remain a dominant factor throughout the history of the whaling industry in Western Australia.

Figure 2.2 Reported returns from whale products exported from Western Australia 1836–1880.

Figure 2.3 Whale products as a percentage of total value of exports from Western Australia 1836–1880.

An immediate consequence of whaling was the major drain on the colony’s labour market. As already described, the low population and indenture system still placed free labour at a premium, so that the loss of 40 or more men to exclusive employment in the whaling parties near Fremantle was sorely felt (Moore 1884:307). As one newspaper reporter commented;

you will meet with few labourers, no matter what description, but follow the hue and cry "in for spouting!" This sound is not most agreeable to those who are following different pursuits and require labourers. It is an idle infatuation, for nine-tenths are not fit to pull an oar (PG 22/4/1837).

Experienced boatmen were the most sought after and there were complaints about the scarcity of fish at the markets as a consequence of nearly all of the fishermen having been employed by the whaling parties (PG 15/7/1837). Although the labour shortage at the Swan River obviously caused some inconvenience, this should be seen from the perspective of the south coast situation, where the 24 or more men engaged in whaling represented at least 20% of the total male (not necessarily adult) population.

The social consequence of whaling that is the hardest to define but perhaps was the most significant at the time is the sense of excitement that the new industry obviously produced in the settlers. Life in the Western Australian colonies was difficult, often disappointing and despite occasional organised events which were not necessarily accessible to all classes, quite dull. As a result, the spectacle of whale hunting immediately became a favourite entertainment, with lengthy accounts of proceedings appearing in the colonial papers throughout 1837. In addition there was the psychological effect of seeing a colonial industry achieving 'instant' success, without the slow, difficult and often uncertain processes involved in agriculture or pastoralism. Amongst the settlers there was 'no talk now but of 'lays' and 'spouting', and other technical whaling terms' (Moore 1884:307). Another report stated that the whole of Western Australia had gone 'mad for whaling', it being 'the chief topic of discourse of all classes, sexes and ages' (PG 6/5/1837). Even though the season itself was only partially successful, the achievements of the whaling industry effectively raised the morale amongst the European population.

The arrival of foreign whaling vessels at both Albany and Fremantle during 1837 heralded the emergence of an external but highly significant influence upon the colonial whaling industry. American whaling ships had been present in the region for several years, mostly trading with the small and isolated outpost at Augusta (Molloy 1834), although there is little evidence that they had engaged in industrial activity prior to 1836. The 1837 season appears to have been aimed at testing the viability of the region, with the American captains intending to send for other ships should they prove successful (CSR 52/142: 24/3/1837).

The threat to the local whaling industry offered by these foreign whaling vessels, as they 'swarmed' about the coast (PG 15/4/1837) was immediately obvious to the settlers and calls for protection were soon made (CSR 53/43: 14/4/1837). The situation was defused temporarily during 1837 by the American captains entering into arrangements with or providing equipment to all of the south and west coast parties, as described above. However, the local authorities began their first tentative enquires of the Colonial Office and Admiralty in England 17to define the rights of American and French vessels to fish along the coasts (CO 18/198: 4/7/1837).

Rather than the expansion that might have been expected from the partial success of the 1837 season, the years between 1838 and 1842 saw a rapid decline of the colonial whaling industry. While there had been four parties operating during 1837, the following season saw a reduction to three stations and one 'tonguing party' that salvaged blubber from the whale carcasses discarded by pelagic whaling vessels. This decreased to two parties in 1839, with the fall continuing over the next three years (Figure 3.7) until in 1842 there was only one unconfirmed report of a station in Two People Bay (CSR 112/145: 29/11/1842).

On first examination the failure to develop the whaling industry is difficult to understand, given that in 1838 and 1839 whale products still formed the major export item of the colony, surpassing even the 1837 returns (Figure 2.2). The potential for fishing was still readily visible in the number of whales passing along the coast, and accentuated by the continuing successes of the rapidly growing foreign fleet in the region. However, several factors can be seen as restricting growth during the period prior to 1843.

The first limiting factor was that while the 1837 whaling season had been successful in the broader context of the colony's economy, the individual parties did not return dividends to investors. Despite being formed with far less capital than that projected as required for a four boat fishery, both of the Fremantle parties, inexperienced and beset by problems during 1837, had failed to return their establishment costs. The Northern Company, which also appears to have suffered from poor management (PG 5/8/1837), was forced to discontinue operations and liquidate its assets (PG 17/2/1837; PG 3/3/1838), dissolving soon afterwards (PG 26/5/1838). The Fremantle Company had been more successful and had also attempted to diversify by sealing after the whaling season (SRG 7/12/1837; SRG 21/12/1837). This group was obviously still hopeful of achieving success at whaling, making improvements to the station and calling tenders for supplies in anticipation of the coming year (PG 21/4/1838; PG 12/5/1838). However, it is not surprising that while the settlers could see the potential benefits of a fishery, on an individual level they became reluctant to risk their own money in the pursuit.

Governor Stirling's (1837a) analysis of the future prospects of the whaling industry had revealed this problem, even before the close of the 1837 season (Stirling 1837a: 250, 258). His table (reproduced here as Figure 2.4) projecting the land, capital and labour which would be required for expansion envisaged three levels of operation, the least expensive or submedial level consisting of seasonal shore whaling by the settlers within each region. The medial category required a small vessel to engage in bay whaling, while the most expensive or supermedial category was comprised of fitting out a full sized vessel for pelagic whaling within the region. It is interesting that these levels correspond quite closely with Little's (1969) categories of whaling.

While Stirling portrayed the future of the local whaling industry as very positive, it was only at the point where the colonists engaged in bay or pelagic whaling that appreciable dividends could be expected. At least some of the colonists recognised from an early stage that without a further injection of capital and an expansion of operations there would not be significant profits from whaling, and even before the conclusion of the 1837 season there had been plans for creating a pelagic whaling industry.

As described earlier, the figures presented in Stirling's table, based on the 'present circumstances' of the colony (Stirling 1837a:260), proposed a minimal establishment of four boats, requiring an initial capital outlay of at least £1000 and annual expenses of £1105. However, even with reasonable success the expected clear profit, at least in the first year of operation, would be only about £50, or 5% of the total investment.

In these cases the amount of capital, in proportion to the number of persons, is small, and although the gross returns are great, the net profit remaining is less than any other vocation.

The initial meeting resolved that the capital would be £5000 in shares of £25 (to be paid in instalments), with the aim of purchasing and equipping a ship in England (PG 15/7/1837). One feature of its prospectus was reported to be a rule forbidding any foreigner from holding an interest in the company, an obvious reproach to the other Fremantle parties (SRG 27/7/1837). Despite grand intentions, by the opening of the 1838 season the company was unable to raise the desired capital and scaled down its plans to opening a small shore station (PG 5/5/1838; PG 21/4/1838).

It is clear that while the colony's economy was steadily growing, there were still only limited reserves of liquid capital with which to invest in an expanded venture. The formation of the original two Fremantle whaling companies, both of which were based on far less capital than the £1000 suggested in Stirling's (1837) submedial category, had required a broad joint-stock investment from a number of major settlers. There simply was not the cash to raise the £2500 required of Stirling's medial (bay whaling) level, or the £5000 proposed in the Western Australian Whaling Company's scheme, a situation which Stirling was forced to admit at the end of the 1838 season

It is now perceived that in a small community like this where wages are high and provisions dear, and where the proper description of vessel cannot at present be procured, the bay fishing labours under great disadvantages, and will not yield to those who undertake it a large profit (Stirling 1838).

Stirling and other agents began a more active campaign to promote the colonial fishery in the hope of attracting English investment. The main argument was 18that if British whaleships based themselves in the colony, the time and expense saved in not having to refit and undertake the lengthy voyage south would make them directly competitive with the American and French fleets (Stirling 1837a, 1838; PG 20/10/1838). This overture was in most respects a reiteration of the proposals generated by the eastern Australian colonies a decade or two earlier (Morton 1982; Chamberlain 1988), receiving new vigour when combined with growing colonial resentment against foreign whalers.

The theme of presenting the whaling potential of the Western Australian coast as a significant British resource being lost to foreign powers was to become a familiar part of colonial promotions (Buckton 1840; Anon 1843; Andrews n.d.). In later years, almost until the close of the industry in the 1870s, this would expand into a discussion of the failure of the British Southern Fishery to take advantage of the situation (Inq 20/7/1870; Knight 1870). Despite the obvious potential of such a move, by the 1830s the British whaling industry was in decline (Jackson 1978) and neither these nor similar proposals from New Zealand (Enderby 1847; Morton 1982) inspired renewed interest.

The reluctance of both colonial and British capitalists to invest in whaling might also be traced to the massive fluctuations in the oil market during this period. As a result of existing surplus and continuing competition between British and American suppliers, the price of black oil on the London market had dropped from above £45 per tun in 1837, down to only £20 per tun in 1838 (Chamberlain 1988:48). It was not until 1843 that prices returned to their former level, and this in part can be seen as a factor in the recovery, or at least re–establishment, of the Western Australian whaling industry after this date.

The continued inability of the colonists to engage effectively in the whale fishery, while watching the rising numbers and continuing successes of the foreign whaling vessels along their coasts, resulted in a growing frustration during the late 1830s and early 1840s. Several contemporary writers attempted to estimate the size of the foreign fleet in the region, the first being a report of May 1838 stating that up to that time 40 American whaling ships had touched on the coast for provisions (Buckton 1840).

Figure 2.4 ‘Table illustrative of the Combinations which take place in respect of Land, Capital, and Labour, in Colonial Pursuits’ (reproduced from Stirling 1837a).

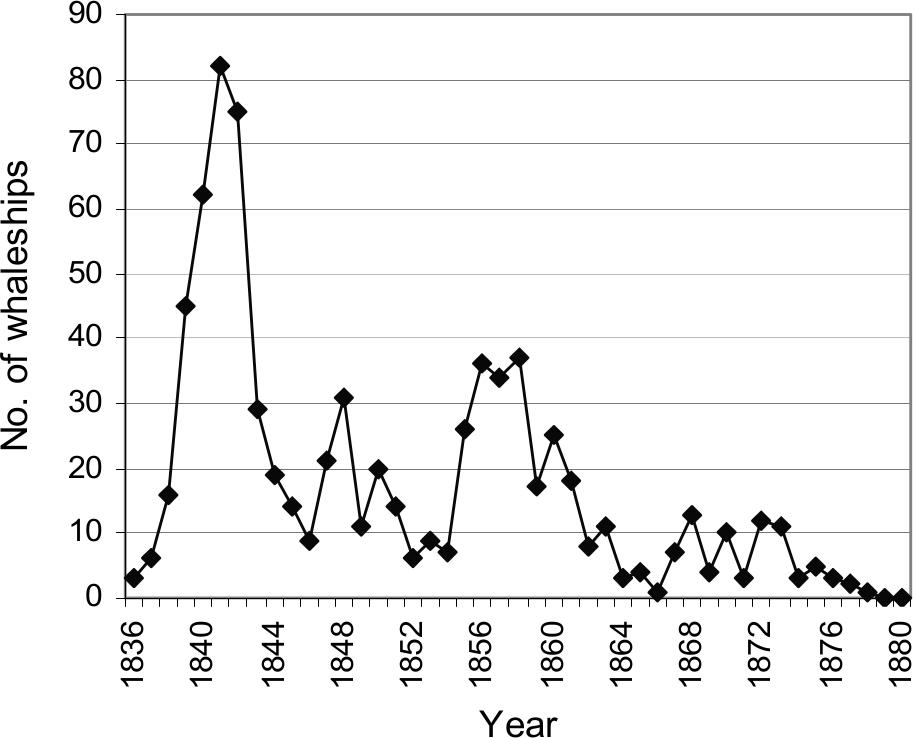

19In 1841 William Nairn Clarke, editor of the Inquirer, reckoned that 150 American whaling vessels appeared annually in Western Australian waters (Inq 1/9/1841). Another commentator suggested there were between 200 and 300 foreign vessels in the 1840 or 1841 season (Anon 1842). As a means of independently assessing the extent of this foreign activity and the probable impact upon the local whaling industry, a database of all whaleship sightings along the Western Australian coast was compiled. Although the large amount of foreign whaling in areas away from the settlements prevents a complete listing of vessels in the region, the trends revealed in Figure 2.5 show that the years between 1840 and 1842 certainly represented a peak of foreign activity. From this evidence, it is conceivable that Nairn Clarke's estimate of 150 ships (Inq 1/9/1841) may have closer to accurate than previously thought. The database of foreign whaling vessels, primarily consisting of American (U.S.) ships, is available (Gibbs 1995) with an analysis of the American whaling activity provided in another paper (Gibbs 2000).

Figure 2.5 Foreign Whaleships reported in Western Australian Waters 1835–1880.

It was not possible to determine the number of whales killed or the quantity of oil removed from the coast by foreign whalers (although see Bannister et al. 1981). Despite the lack of statistical data, the constant stream of reports in the colonial press clearly suggests that the ocean about Western Australian, also known as the New Holland Ground, was a highly productive area. The pelagic whalers would hunt the sperm whales offshore during the appropriate season, then retire to the coast to bay–whale while 'wintering' (Gibbs 2000). One frequently cited example was that two American and one French ship stationed at Two People Bay had taken catches worth nearly £27,000, almost wholly from the W.A. coast, in a period of less than two years (PG 1/12/1838; Buckton 1840). Other reports gave similarly impressive figures (Inq 3/8/1842; CO 18/20:41 3/12/1838; CO 18/26:281, 30/6/1840).

It was usually while they were wintering along the coast that the foreign vessels came into conflict with local whaling parties (Gibbs 2000). In the direct competition of chasing the same whale, the colonials stood little chance against the experienced and well–equipped American boats. Vessels anchored in adjacent bays could also compete indirectly, either by catching the whales before they passed through to the bays where the colonial parties were resident, or by galleying (frightening) the whales through chasing them, making them wary of other boats (CSR 189/254: 13/8/1849). This situation was exacerbated by the colonial strategy of establishing shore stations in locations previously used by the foreign vessels (see Chapter 4).

Repeated calls were made by the colony for the British government to provide some form of protection for the fishery. These were usually combined with attempts to generate interest amongst British investors. In 1837 Stirling sent a detailed dispatch to England, requesting action to restrict foreign whaling (CO 18/18:198, 4/7/1837), although it was to be several years before a response was received. Meanwhile, tensions rose and rumours circulated, with one eagerly received report being that Lord Glenelg had intimated that a man–of–war would be sent to patrol the Western Australian coasts in the following season (PG 8/12/1839).

Colonial Office correspondence (CO 18/23–30) reveals the lengthy discussions between various individuals and committees in England, weighing the situation and possible responses or actions. However, the uncertainty as to the rights of the American whalers, as well as the difficulties which might arise from any attempt to remove them, resulted in guarded responses such as that from the Board of Trade.

By the Law of Nations the inhabitants of every country have the exclusive rights of fishing within three miles of low water mark, upon the coast and harbours thereof, unless the subjects of other states have, by treaty or immemorial usage acquired the right to fish therein… I can not, however, undertake to advise that Great Britain has any just right to exclude foreigners from fishing on such parts of the coast of Western Australia as are not in British occupation. (CO 18/29: 54, 25/1/1841)

There also appears to have been a body of opinion, revealed in margin notes and memoranda, that it was not necessarily beneficial to the Western Australian colony to have the foreigners driven away (CO 18/25: 54, 15/2/1841; CO 18/29: 24, 29/1/1841). As the colonists were unable to engage in the fishery themselves, it was felt that the Americans were not depriving them of any advantage. Instead, the Americans resorting there and providing 'a large… and reliable market for various commodities produced there' was promoting the international interests of the settlements.

The belated response of the Queen's Advocate followed these opinions, stating that the American 20whalers should be informed that Great Britain denied their right to fish within three miles of the shore of bays and harbours occupied 'bona–fide' by British subjects (CO 18/25:54, 15/2/1841). However, force would not be resorted to, except if especially directed by the Secretary of State should 'some aggravated case warranted remonstrance' (HRA I (21): 268–69, 9/3/1841; PG 30/1/41). New Zealand, which was also complaining of foreign whaling encroachments, received a similar response to their requests for assistance (HRA I (21): 270, 26/2/1841).

Despite their obvious inability to enforce any directives, the colonial authorities attempted to apply the three–mile limit on the settled bays of the colony, including the bays in which local whalers had established themselves. In 1843 the Government Magistrate of Albany posted a notice stating that foreign ships interfering with bay whaling establishments risked seizure of their vessels (CSR 119/99, 22/6/1843). On the west coast foreign vessels were also advised of the three mile limit and told that as Geographe Bay was considered a settled bay they were not to fish beyond a line drawn due east from the head of Cape Naturaliste to the opposite coast (Heppingstone 1969). While the American whalers generally abided by these conditions, they were well aware of their role in the coastal exploration of the region and responded accordingly.

I hereby acknowledge receipt of a copy of a letter from the Colonial Government in which they say we have no right to whale in this bay, but at the same time do not intend to interfere with us so long as there are no English whalers at the same place. This act of courtesy I consider our due for having found and proved the best anchorages on this coast such as Doubtful Island, Cape Riche and Two People Bay, Geographe, Leschenault and Safety Bay all of which have been proven by Yankee enterprise. (CSR 85/82, 24/1/1840)

Although the American whalers normally avoided confrontations, possibly for the sake of continuing trade relations, there are numerous references to foreign ships fishing adjacent to settled areas and even in close proximity of Fremantle. Whitecar’s comments during a visit to King George Sound in 1856 may well sum up the American attitude.

It is the law of the English Coast, that no fishing should be carried on within three miles of the coast of colonies. This law is a dead letter in the Indian Ocean, excepting where their fisheries exist; and I am sure that, had whales made their presence in this bay whilst we were present, our boats would have been down among them. (Whitecar 1860: 219)

This situation lasted until at least 1860, when it finally became possible to pass and enforce legislation preventing foreign whaling.

Beyond the cautious and sometimes strained relationship with the colonial whalers, the trade activities of the foreign whalers became a major factor in the early survival of most of the coastal settlements outside Fremantle. Despite Churchward's (1949; 1979) claims to the contrary, the commercial interaction was clearly two–way, with the American whaleships forming both a significant export market and an important source of imported goods. For the foreign whalers the small settlements provided a valuable opportunity for obtaining wood, water and food supplies without having to return to Batavia, Sydney or New Zealand. As suggested by the Colonial Office, for the colonists the pelagic whalers became consumers for produce that would not otherwise have had a market.

The initial appearance of American whalers at the main ports had been heralded with high expectations of developing a profitable commerce in supplying them with produce (PG 18/2/1837). Unfortunately, greed and poor judgment on the part of the colonial merchants and administration appears to have impeded the opportunity for developing the market to its full potential. Complaints from the American captains with regard to the prices of produce and the port fees at the major harbours emerged in early 1839 (PG 23/2/1839). These were not taken seriously until 1842 when, after several unheeded warnings about the slack attitude towards providing reasonable services, the Americans stopped calling at Fremantle and Albany (PG 5/3/42). It was not until 1846 and the repeal of the harbour fees that American ships returned to those ports (Inq 29/4/1846).

In contrast to the main settlements healthy commerce continued at the more isolated harbours, particularly Augusta, with the increasing demands for produce amounting to thousands of pounds of income (e.g. Inq 3/8/1842; Inq 26/4/1843). In an admirable feat of entrepreneurship, in 1842 George Cheyne established a private anchorage and supply base for the whalers at his Cape Riche property, 90 kilometres east of Albany (PG 18/11/1843). It was reputed to afford a high standard of service and not only could vessels be provisioned there without having to pay port fees, but the captains also did not have the worries of desertion or drunkenness that usually attended visits to the larger settlements.

In addition to the sale of provisions, the inhabitants of the smaller ports (and to a lesser extent Fremantle) were also able to purchase from the Americans a range of commodities that were often in short supply by normal means. This included smuggling of spirits and other items to avoid payment of duty and taxes; a relatively easy process given the vast and largely unpoliced coastline. Both sides were also willing to engage in barter; a situation that gave the Americans increased purchasing power and allowed the colonists to preserve their limited supply of currency. In the early years of the settlement this helped fill the gap created by irregular supply from England and uncertain distribution through the coastal trade.

21Whaling vessels, particularly those which made repeated visits to the same ports, also provided an important social outlet for the remote settlements, with this contact obviously valued by the whalers as well (Shann 1926; Hasluck 1955; Gatchell 1844; Jennings 1983). Detailed examination of relationships with foreign whalers is provided in Gibbs (2000).

CONSOLIDATION (1843–1869)

The years between 1843 and 1869 represent the main period of shore whaling in Western Australia. Whereas the preceding phase might be seen as one of experimentation, it was during this phase that the patterns of station organisation and operation by which the industry can be characterised were established. Although there is no clear dividing event, two main stages can be distinguished. From the re–commencement of whaling in 1843 until the mid–1850s was a time of expansion, with new operators entering the industry and new locations and modes of organisation being tested. This gave way to a period of stability that saw little change within the industry, lasting until a decline in activity in the late 1860s. While the broad historical development of the industry is documented here, specific aspects of the organisation and operation of the whaling in Western Australia are examined in Chapters 3 and 4.

Re–establishment of the colonial whaling industry occurred amidst a variety of forces that both encouraged and limited its potential scope. The first several years of the 1840s had seen Western Australia experience buoyant economic activity which included an increase in immigration. However, this changed during 1843 when a dramatic drop in new settler arrivals, increased government expenditure and falling livestock and grain prices combined to throw the colony back into an economic recession. An unfavourable balance of trade also developed, once again reducing liquidity as capital was lost through high import payments (Statham 1981a). It is probable that part of this decline can be attributed to the recently lost trade with the American whaleships.

The Governor appealed to the settlers for help in redressing this situation, urging them to reduce their imports while exporting as much colonial produce as possible (Inq 8/5/1844; Statham 1981a). It was in this period of searching for potential export items that attention was once again drawn to whaling. The recovery of international oil prices to the pre–1838 high of £45 per tun (Chamberlain 1988), combined with the still obvious potential for a successful fishery along the coast, provided further incentive for local merchants. One south and one west coast party had started operation by mid–1843, and in the following year that number had doubled (Figure 3.7). By late 1844 the export earnings of the new whaling ventures and other industries fostered under the Governor's campaign had successfully reduced the effects of the recession (Statham 1981a).

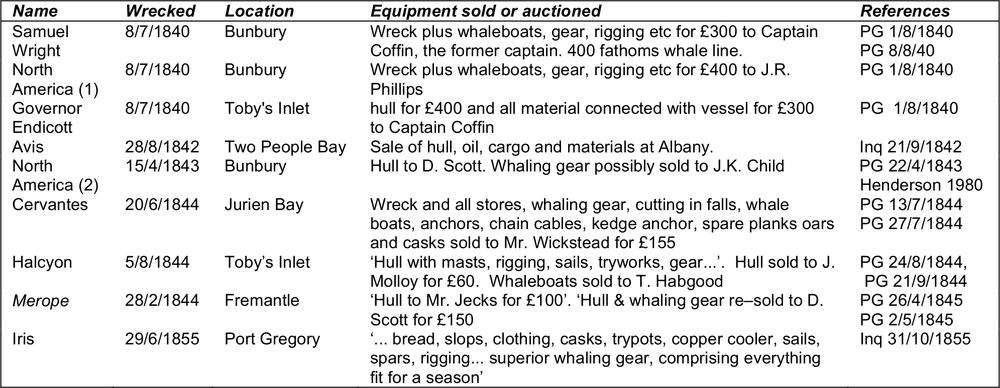

The relative ease with which the settlers were able to re–commence shore whaling despite the surrounding economic difficulties might be traced to the unexpected increase in availability of cheap whaling equipment in the colony. During the first half of the 1840s over half a dozen American and French whaling vessels were wrecked along the south and west coasts of Western Australia. Rather than attempt to repair and refloat their vessels, the captains chose to dispose of the hulls and all of the whalecraft on board (Table 2.1).

These pelagic whaleships carried enough whalecraft for their three to four year cruise, which was sufficient to completely equip two or more shore stations. Most notable was the fact that the prices received at auction for these cargoes was usually under £400, significantly less than the costs of purchasing and importing equipment from England, and without the prolonged delays in transport. In particular, if the vessel was at the end of its voyage and had a full cargo of oil, the master would quickly dispose of all of the whalecraft as a means of maximising profits from the cruise (Whitecar 1860). The body of cheap whalecraft now amassed in the colony, together with further development of associated manufacturing and service industries, markedly reduced the establishment costs that had bedevilled the local industry.

The labour market had also been slowly growing and there was now a body of men with prior whaling experience, including a fluctuating population of deserters from foreign vessels. There rapidly evolved a situation where a relatively small amount of capital, maybe even the £300 mentioned by Blainey (1966:111), was sufficient for a colonist to form a small whaling party. In addition to the cargoes from the wrecks, visiting American whalers were often willing to sell surplus equipment to local fisheries and merchants. The whaling parties that emerged during this phase of re–establishment were more modest than those seen prior to 1843. Whereas the Fremantle and Northern whaling companies were large stations that had expended much of their capital and effort in developing fixed assets, the new parties appear to have opted for a smaller and simpler scale of operation (Chapters 4 and 5).

Although there is little historical evidence on the nature of the stations, they were generally only two or three boat fisheries, with facilities limited to basic processing plant and huts for between 13 and 21 hands. It is possible that this reflected the nature of the leases, which were annual and saw all improvements revert to the government at the end of the term.

It was this clause which had sealed the fate of the Northern Company, only emerging when the company had tried to save itself by attempting to sell the Carnac Island station back to the government 'for a reasonable consideration' (PG 24/3/38). However, as the industry stabilised the continuing associations of particular parties with particular station sites created a security of tenure that allowed them to develop their facilities with only a limited risk of removal or resumption. 22

Table 2.1 Whalecraft sold from wrecked American whaleships 1840–1855.

The simpler operation and decreased overheads of the whaling stations also saw the emergence of less elaborate financial structures. Ownership of most of the stations can be traced to a single investor, or small partnerships of several local merchants and landowners. The Fremantle Whaling Company still existed, although the directors increasingly chose to lease the station to individuals in return for a fixed rent or a percentage of the catch, rather than engage in organising a whaling party themselves (PG 3/5/1848).

While various arrangements were still being made between American and colonial whalers (CSR 131/59: 31/7/1844), no evidence has been found to show that either foreign or eastern Australian interests were financing any of the Western Australian parties. Except in the broadest market–related terms, the continuing development of the colonial whaling industry apparently remained independent of the interests of other Australasian whalers. It is, however, worth reiterating that other Australasian whalers had also been adversely affected by the economic difficulties of the 1840s. Combined with diminishing whale stocks and reduced returns, a similar pattern of closure or simplified operations obtained and is often taken to mark the 'end' of shore whaling (Dakin 1938; Morton 1982; Campbell 1992; Nash 2003).

The 1840s and early 1850s saw the formation of a succession of small whaling parties on both the south and west coasts of Western Australia. Many of these groups were short–lived, surviving no more than one or two seasons before being sold or disbanded (Chapter 3). It is difficult to determine the cause of this high turnover, although it is probable that inexperience still played a large part in local difficulties.

The total annual number of whaling operations across both coasts remained at half a dozen parties or less, usually with a higher concentration on the west coast. Although analysis of historical sources suggests that all whaling parties have been accounted for, the poor communications of the period, particularly between the south and west coasts, allows the possibility that there may have been other small or short–lived stations which have not been identified.

Several new locations were tested, including some of those used in the first years of the whaling industry (see Figures 4.1 and 4.2). Possibly as a result of the limited number of suitable bays, the west coast fisheries were generally situated in or adjacent to the harbours in which settlements were or soon would be located. This created an association between whaling and hinterland development, although not necessarily with the direct links to pastoralism seen in Eastern Australia (Little 1969).

In contrast, the greater range of suitable locations along the south coast saw shore parties rapidly spread beyond King George Sound, even though settlement was to remain focused around Albany. The process of selecting suitable locations and the histories of individual stations are discussed in detail in Chapter 4.

Two brief sorties into bay whaling occurred during the 1840s. The first began in 1841, with the purchase of the barque Napoleon by Daniel Scott and a Liverpool syndicate (Heppingstone 1973; Inq 21/7/41; PG 16/7/41). Although there were several brief periods of whaling along the Western Australian coast, the ship's log shows that most of the time she was engaged northwards between the Timor Sea and the Sulu Sea (BL 239A/1). In late 1844 she was loaded with cargo and set sail for England, but did not return to Western Australia.

The second episode was with the English barque Merope, which had been driven ashore at Woodman's Point during a gale and then was also sold with all of her whalecraft to Captain Scott (PG 1/3/1845, Inq 5/4/1845, PG 3/5/1845). Once re–floated, Merope remained a more consistent presence along the Western Australian coast. In late April of 1846 Merope under Captain Harding sailed for the sperm whaling grounds (PG 25/4/46) but at a later date also bay whaled at Augusta and assisted the Castle Rock shore station. After being given English registry Merope was then sent to England with a cargo (CO 18/47:25, 17/2/1848) and is not thought to have returned to Western Australia. In both the cases of Merope and Napoleon it is hard to determine if whaling was ever the 23primary purpose of the vessels, and if it was, why they failed to pursue it more vigorously.

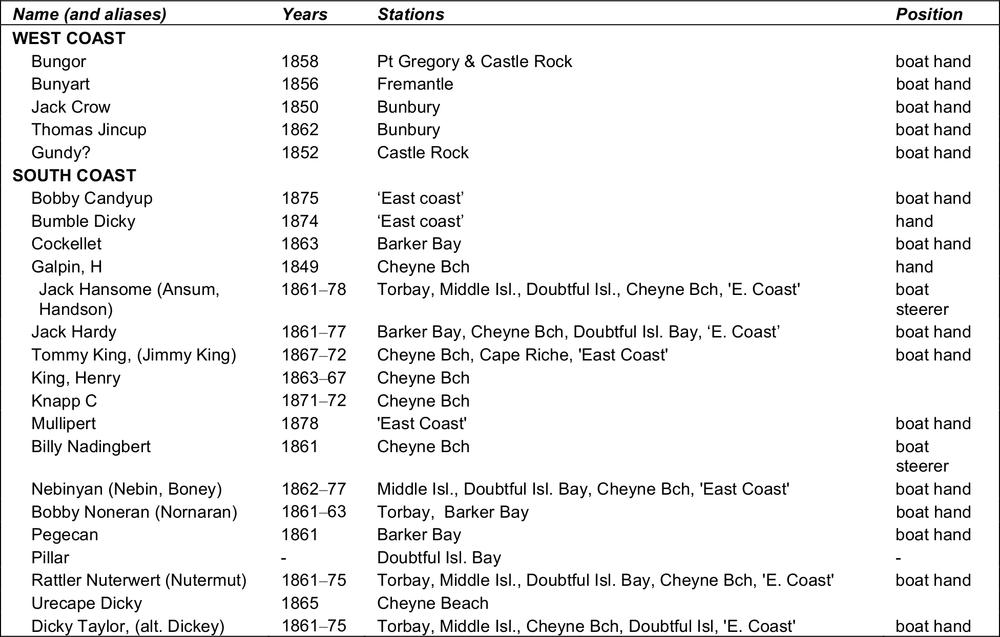

Between 1843 and 1846 various stations reported disruptions or desertions by whaling hands, sometimes impeding operations and resulting in the loss of whales. Although the offenders in at least two of these incidents were sentenced to imprisonment with hard labour (Inq 3/9/1845), there were calls for a revision to the law of engagement to provide better regulation of whalers' conduct (Inq 10/9/1846). The potential of continued disturbances to damage the success of the fishery was obviously considered serious enough to result in the passing of an act to allow articles of agreement to be drawn between whalers and their employers (Statutes of Western Australia, 10th Victoria, No.16, 1847). The contracts worked in favour of the station owners, allowing them to punish breaches of contract with a range of penalties from fines to imprisonment. It is not known if anyone was prosecuted under these regulations, although analysis of known whalers and their positions within the parties provides an important insight into both the nature of the parties and the men who worked in the whaling industry.

From the mid–1840s the Blue Books (government statistical reports) provide a regular annual record of oil and bone returns from each region, together with the estimated value of the catch and export returns from oil and bone during that year. Although not complete, these figures reveal that the industry as a whole was achieving reasonable catch success (Figure 3.22) and until the early 1850s producing a moderate export income (Figure 2.2). Unfortunately, the peak in oil prices after this time (Chamberlain 1988) was not met with a corresponding increase in colonial production or export returns. In the context of the rest of the colonial economy, wool and sandalwood had significantly overtaken whale products as the major export income earners. The contribution of whale products fell below eight percent by 1849, and by 1861 it had dropped below two percent (Butlin et al. 1987: 122).

The presence of, and occasional direct competition with, American whalers continued to be a factor in the fortunes of the local shore stations, with several incidents and complaints reported during 1844 (PG 11/5/1844; Inq 16/10/1844). Undoubtedly, the intensive fishing which had taken place since 1837 had also considerably reduced the coastal whale stocks of the region, seriously decreasing the opportunities for the colonial stations. The repeal of port fees (Inq 29/4/46) saw a slow return by foreign vessels to the major ports, although by this time Western Australia had lost the opportunity of becoming a major supply base for the American fleet. Figure 2.3 shows that after the peak of the early 1840s the number of American vessels in the region declined rapidly, hastened in the late 1840s by the loss of ships and men to the Californian gold rush (Gibbs 2000).

An important aspect of the Western Australian whaling industry that becomes evident during the 1840s is the complete separation of both management and activity between the west and south coasts. Although officially part of the same colony, the settlements at Albany and the Swan River were for many years divided by a sea voyage that lasted a week or more. While joined in the broader administrative and economic sense, they were in most respects separate colonies, pursuing their own patterns of development.

With regard to the whaling industry, no evidence has been found to suggest interaction between merchants, investors, or even workers in the south coast parties with their counterparts along the west coast. This separation also extended to physical boundaries, with the difficulties of rounding Cape Leeuwin and Cape Naturaliste creating a formidable natural barrier against movement between the two regions. Such a voyage was well beyond the capabilities of the small colonial whaling parties, resulting in south coast shore whaling activities only extending east of Torbay, while the west coast parties did not pass south beyond Cape Naturaliste.

This dichotomy in the colonial whaling activity, which lasted until the close of operations in the late 1870s, meant that Western Australia effectively had two whaling industries. This presents possibilities for comparison between the two regions, some of which will be explored in later sections. However, the remainder of this narrative will continue to follow broad developments and influences within the colony as a whole, and treat the whaling activity on both coasts as a single entity.

June 1850 marked a major turning point in the social and economic development of the Western Australian colonies, being the point when that the first shipload of convicts arrived from England. Although many sectors of the Western Australian community retained the anti–transportation stance that had predominated since colonisation, a concerted campaign by the powerful pastoralist body known as the York Agricultural Society forced the change in policy.

By the mid–1840s, the further development of the agricultural, timber and pastoral industries had once again created a shortage of free labourers in the colony. As a result, these men were able to demand extremely high wages and conditions for their seasonal or contract employment, causing discontent among the employers. It was the pastoralists, wealthy, well organised and politically connected in both the colony and England, who led the push for convict labour. Their ostensible motive was that the introduction of convicts would have wide reaching benefits for the colony through the completion of public works, the introduction of Imperial expenditure to support the system, increased land values and the lowering of food and other prices. However, their actual purpose was clearly to break the labour situation by introducing a flood of cheap and controllable workers (Statham 1981b).

The arrival of the convicts, their guards and the Imperial funding that sustained the system certainly did produce some of the effects predicted by the York Agricultural Society, although an economic boom period did not result (Statham 1981a; Gibbs 2001). With respect to the whaling industry, it can be supposed that the change in the labour market did have a flow–on effect in 24making men available for employment. Convicts themselves were not allowed to be engaged on boats for the obvious reason of the escape opportunities so offered, although some stations did try to obtain permission to use ticket–of–leave men (convicts allowed to seek employment from free settlers) in their parties.

The second important change in the early 1850s was the spread of European settlement beyond the original boundaries of the southwest. The colonial administration had previously been loath to stretch its limited resources and consequently had restricted any expansion of settlement above the Swan River. However, the discovery of minerals in the lower Murchison region in the late 1840s, together with pressure from the York Agricultural Society to open new pastoral runs, resulted in the 1850 decision to establish new outposts at Port Gregory and Champion Bay (Geraldton), some 450 km north of Fremantle (Bain 1975). By 1854 one of the major settlers at Port Gregory, Captain Henry Sanford, had established his own whaling party. Two years later he had gone into partnership with Fremantle whaler Joshua Harwood, while John Bateman had also sent crews into the area.

By the mid–1850s the whaling industry on both coasts had entered a period of stability. Out of the many owners and operators seen during the preceding phase a number had survived and were now joined by several new figures to become a consistent presence until at least the end of the 1860s. On the west coast there were Bateman, Harwood and Heppingstone, with the latter's son–in–law George Layman inheriting the Castle Rock operation after his death in 1858. On the south coast there were Thomas, Sherratt and McKenzie. Many of these men were the second generation to be involved in whaling in Western Australia, had worked their way through the local industry and were now taking an active part in the operation of their own parties, usually as headsmen.

Although most of the whaling parties remained closely associated with particular stations, there was an increasing trend towards using more than one station during a season, following the whale migrations. On the west coast this had come into practice with the occupation of Port Gregory, with both Bateman's and Harwood's groups starting in the north before moving southward to Fremantle or Bunbury to catch the later season. As this system developed, it appears that parties were sometimes maintained at both a northern and southern location, with the former group later returning to strengthen the Fremantle operation, or passing directly southward to a new position.

Similar developments were to occur on the south coast, although at a slightly later date. Albany had remained a small and depressed village, servicing American whaleships and the occasional P&O Company steamer, with shore whaling still forming an important component of the local income. There had been some hinterland development, but it was not until the 1860s and 1870s that small pastoral communities began to develop along the coast to the east of Albany at Bremer Bay, Esperance and later at Eucla (Garden 1977:135). After a slump in the 1850s, the south coast whaling industry had managed to revive to three small parties operating in and around King George Sound. There are a few reports from this time which suggest that the whaling parties had begun to split their seasons, spending the later half at stations around Cape Arid and Middle Island, about 550km east from Albany (Inq 12/11/1862; Sale n.d.). Although there was trade between the whalers and the few European settlers of these remote areas (Erikson 1978), it is hard to demonstrate a direct association between the opening of the pastoral frontier and the eastward movement of the whalers.

Despite this increased effort, the individual stations on both coasts were no longer making the sorts of catches seen in the 1840s. The estimated value of the annual yield fluctuated between £1000 and £4000 per season (Figure 3.25). Export earnings also averaged close to several thousand pounds per year (Figure 2.1), which was now a negligible component of the total colonial economy (Figure 2.2). A rise in local consumption of oil resulting from increases in population and public amenities must also have reduced the availability of oil for export. Another major influence was the discovery of petroleum in Pennsylvania in 1859, although it was to be another decade before the sale of kerosene would begin to have a serious impact upon the local and international whaling community (Whipple 1979).

In 1858 an incident occurred near Fremantle where it was claimed that the boats of the American whaler Lapwing had deliberately 'galleyed' or frightened a whale as one of the local whaling parties attempted to harpoon it. Joshua Harwood, the owner of the shore station, attempted to sue Captain Cumiskey for £600 damages and is reported in contemporary papers as settling out of court for £300 (Inq 23/2/1859; Inq 6/4/1859). However, Heppingstone (1969) suggests that this amount was awarded by a jury, followed by a successful appeal which resulted in the judge ruling that Americans were friendly aliens with acknowledged rights to fish in British waters (Inq 23/2/1859; BL Acc. 991).

The case of Harwood vs. Cumiskey appears to have stirred up many of the old resentments regarding foreign whaling in the region. On the advice of English legal authorities (Heppingstone 1966), the Legislative Council passed an Act in December 1860 entitled ‘An Ordinance to prohibit Aliens and Foreigners taking whales and other fish in the Waters of Western Australia’ (Statutes of Western Australia 24th Victoria, No. 12., 1860). The preamble states that the act was formed to prevent aliens and foreigners in foreign ships and vessels from taking whales on the coast of Western Australia to the prejudice of British subjects and in breach of sovereign rights. Foreigners caught taking whales, or persons aiding such actions, would be liable to fines between £5 and £20, a strangely ineffectual sort of penalty given that each whale yielded many times that value.

Although clearly establishing the legal means of preventing or at least rapidly resolving further situations of conflict, it is hard to determine what real effects the act had on whaling in the area. A fraction of the American vessels seen in previous years now visited the region and 25in the following year these were still being regularly reported at the outports (PG 1/3/1861). The advent of the American Civil War in the same year effected a further reduction in the number of vessels soon after (Figure 2.3). Between 1861 and 1865 Confederate attacks on Yankee whaleships and re–deployment or sinking of vessels as a defensive measure reduced the size of the American whaling fleet by nearly 50 per cent (Whipple 1979:156). When hostilities ceased there was a return by American whalers to the New Holland Grounds off the Western Australian coast, but with numbers tailing off during the 1870s and 1880s.