CHAPTER 5

EXCAVATION OF CHEYNE BEACH WHALING STATION

The historical evidence of shore whaling in Western Australia rarely extends to descriptions of industrial activity, with almost no information on domestic activities at these sites. There are no diaries or descriptive accounts of life on the maritime frontier. Consequently, questions about material culture, diet and the 'lifeways' of the inhabitants of the whaling stations can only be addressed through excavation and analysis of artefacts.

The historical research and results of the archaeological survey generated several broad categories of questions to be addressed by intensive investigation. The first concerned the nature of the industrial workforce and its social organisation and domestic conditions. As described previously, the documentary evidence shows that a Western Australian shore whaling party could be composed of between 12 and 30 men who would work together almost continuously for between four and six months during the coldest and wettest seasons of the year. The majority of the stations were situated at some distance from settlements, meaning that the owner or manager would be expected to provide at least housing and food during this period. As noted in Chapter Four surface surveys generally only identified a single chimney in the domestic area, presumably attached to a wooden structure. Whether these represented a single barrack or the sole surviving chimney of a wider complex is unclear. Similarly, the size or arrangement of building(s) remained uncertain.

The second area for investigation was the material culture of the whalers, both as an example of the lifeways on an industrial frontier and for what it might tell us of the early European settlement of Western Australian. In the first instance the artefacts allow a reconstruction of how the whalers lived and what they used in the context of these isolated camps or communities. In a wider sense it indicates the trade networks which provided consumer items to the small Western Australian settlements that then presumably filtered through to the whaling stations.

Finally, the underlying theme of adaptation could also be followed, with the whaling stations affording insights into how the European settlers of that period dealt with the environment and their remote situations. The focus for this investigation was be the dietary evidence and in particular the balance between domestic and native faunal components. Although the documentary evidence presented in Chapter Three indicates that food was a potentially sensitive issue between employers and workers, the nature of the diet, alcohol consumption and other aspects of domestic behaviour in these remote locations were unknown.

This chapter describes the excavation and analysis of the Cheyne Beach Whaling station. The first section traces the progress of the excavation itself and provides relevant topographic and stratigraphic information. The second section describes the artefacts recovered, using the framework of a functional typology. The final section discusses the evidence of the site and addresses aspects of the questions raised above.

SITE DESCRIPTION

The original intention of the project was to sample deposits from at least one site on each coast to provide a comparative dimension. However, it was eventually decided to focus efforts on a single site in return for a more detailed analysis of lifeways. Cheyne Beach presented several advantages which resulted in its selection. The 1987 National Trust survey (MacIlroy 1987) had already indicated interesting subsurface structural evidence in the form of a floor composed of whale vertebrae. The presence of a well–defined foundation meant that a more detailed analysis of artefact distributions and activity areas might therefore be possible. The second factor was that the Cheyne Beach station was known to have been occupied almost continuously between 1846 and 1877, the longest use of any Western Australian shore whaling station. This not only increased the chances of finding substantial refuse deposits, but also presented the possibility of investigating change over 30 years or more.

Environment

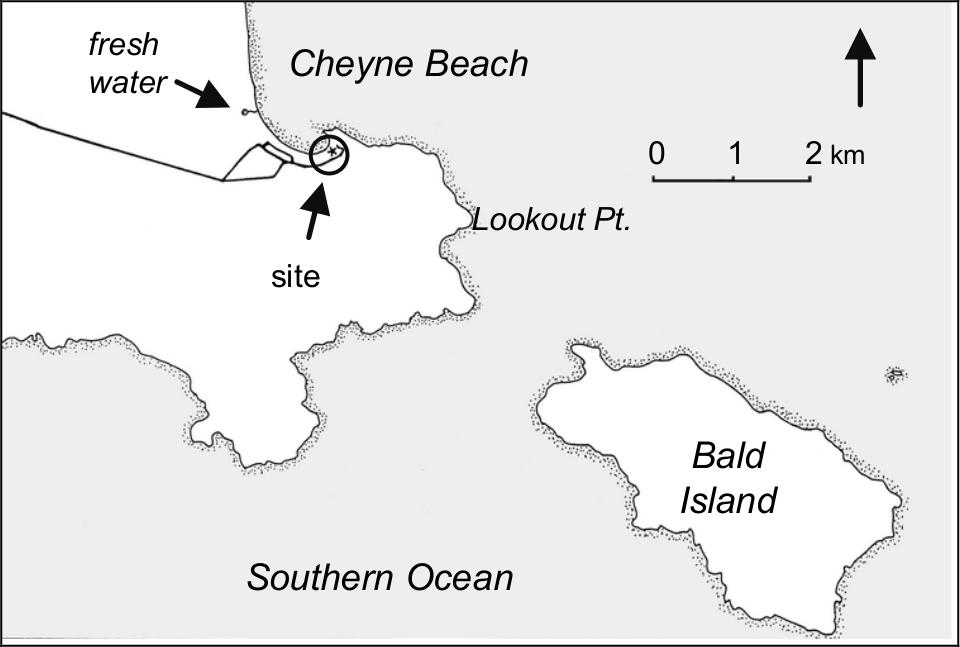

Cheyne Beach is located 50 kilometres northeast of Albany (Figure 2.1) and is the southern–most end of Hassell Beach, a long, sandy bay typical of the south coast (Figure 5.1).

Figure 5.1 Cheyne Beach

Cheyne Beach is protected from the worst of the weather and swells coming up from the Southern Ocean by a range of granite hills which extend south and east 70behind the bay. The granite headland which forms the southeastern point of Cheyne Beach, together with the small reef which extends from it, creates a sheltered harbour although the area is still susceptible to storm surges and cold weather fronts blowing across from the southwest.

Temperatures between June and November, the normal months of occupation of the whaling station, vary from 6°C to 21°C, with August being the coldest month (Beard 1981). Rainfall peaks between June and August, each month having more than 20 days of rain with the area receiving an annual total of about 750 mm. Conditions can fluctuate widely and rapidly throughout the course of a single day, with cold fronts from the south sweeping over the peninsula and replacing sunshine and warmth with rain and cold winds.

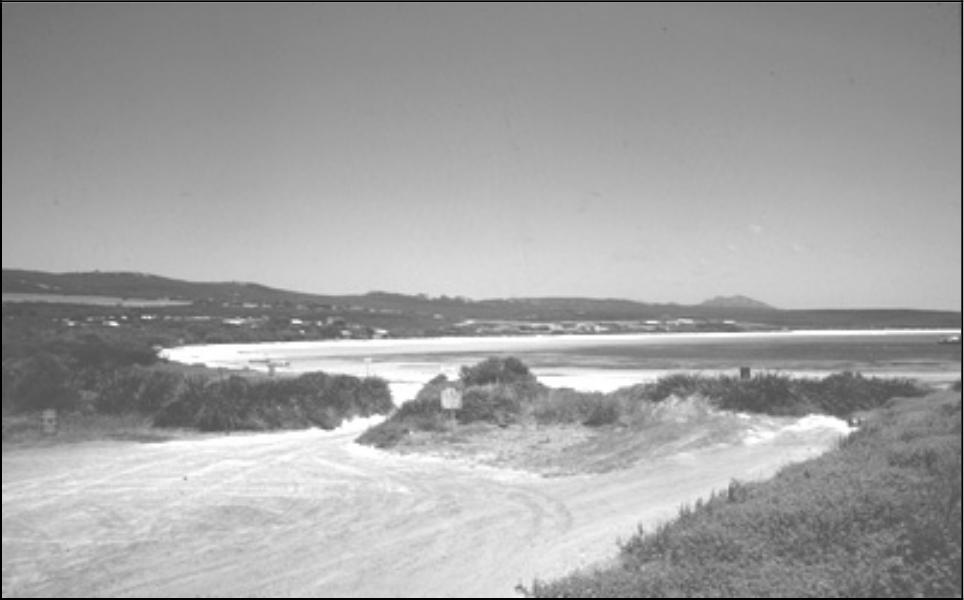

Figure 5.2 Cheyne Beach from south–west

Figure 5.3 Cheyne Beach site from look–out (looking south). Structure One in reeds to right (west) of cars. Squares P93, U93 and Z93 directly beneath the cars.

During the winter months there is abundant fresh water available, with run–off from the granite slopes collecting in the inter–dune swales such as those immediately behind the whaling station site. There is also a perennial freshwater spring and small lake situated behind the dunes approximately one kilometre northwest of the site. The spring water flows onto the adjacent beach and, as suggested in Chapter Four, may have been used by foreign whaleships prior to the colonial occupation of the bay.

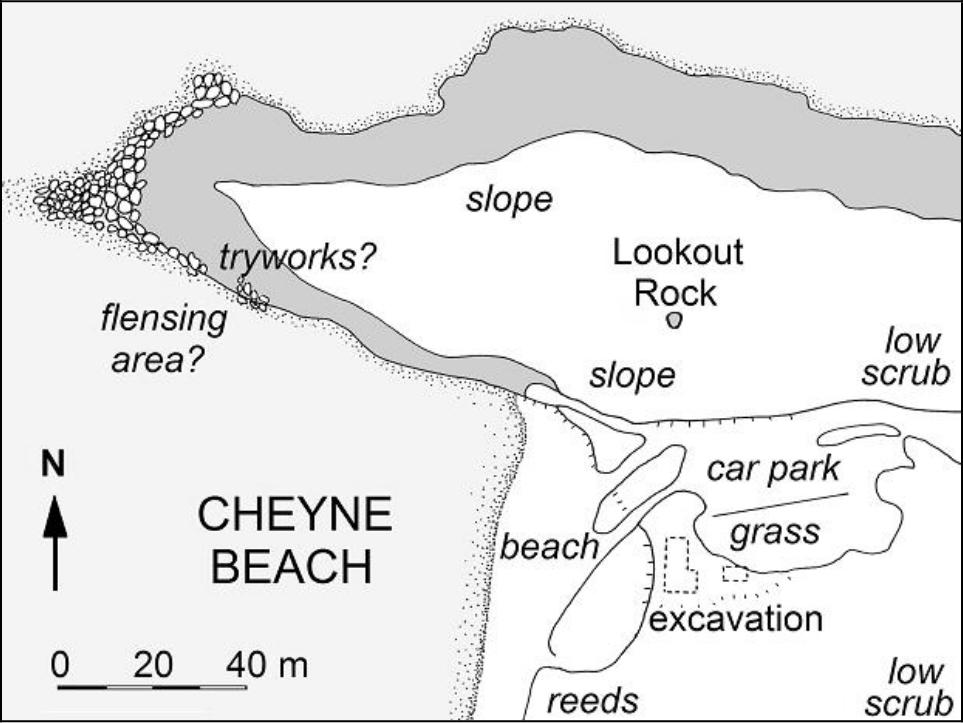

The site of the whaling station is located in the sheltered southeast corner of Cheyne Beach, adjacent to the granite headland. To the west of the station a white sandy beach extends for several meters above the high tide mark, before rising to a low, grassed area which is now used for boat–trailer parking. The eastern edge of this area is marked by the low sand dune, approximately 1.5 to two meters above high tide, on which the structural remains of the station were found. While the dune is heavily vegetated, in the vicinity of the site the natural cover has been reduced to an area of only 15 meters width. Beyond this the ground has also been cleared and levelled as a grassed picnic area, with a gravel car park along the northeast edge. To the southeast of the dune is a low and sometimes swampy area which, as will be discussed below, may have originally extended further north and west of the site and through what is now the picnic area and car park.

Figure 5.4 Cheyne Beach site from north–west Structure One in reeds on left. TP1 located right foreground.

Figure 5.5 Cheyne Beach site plan

The foredune on which the site rests is covered by an extremely dense growth of knotted club rush (Scirpus nodosus) and coast sword sedge (Lepidosperma gladiatum), which then gives way to peppermint scrub (Agonis flexuosa) and tea tree (Melaleuca pubescens), and eventually to sand plain species (Proteaceae, Leguminosae and Epacridaceae) (Storr 1965:191). In 71summary, while there are limited stands of low woodland to a height of several meters, most of the vegetation within several kilometres of the whaling station site is scrub–heath, with no timber suitable for construction purposes. Although there is now a single small farm and a small fishing settlement nearby, much of the area surrounding Cheyne Beach is a floral reserve with the original vegetation relatively untouched.

When the site was first surveyed in August 1989 the area which had been cleared of vegetation and shovel-trenched by the 1987 National Trust survey (MacIlroy 1987) was still visible. The outlines of the excavation could be roughly traced, as could the stone wall which forms the southeast corner of what is referred to below as Structure One. However, further survey through the dense sword–sedge to either side of this clearing proved almost impossible, as the only means of passing over the area was to literally wade through the vegetation while walking on a pad of reeds at least thirty centimetres or more above ground level. This also made it unfeasible to either see artefacts and features or even detect indicative variations in the surface level. As the reeds are also prime habitat for several poisonous snake species, great care had to be taken at all times.

The work permits from the Shire of Albany required any clearance of vegetation be strictly limited to those areas under excavation to try to reduce foredune erosion, with re–vegetation to follow. This prevented a more widespread clearance for the sake of survey or more extensive excavation. It also was not permitted to disturb the surface of the car park, situated adjacent to the site.

EXCAVATION METHOD

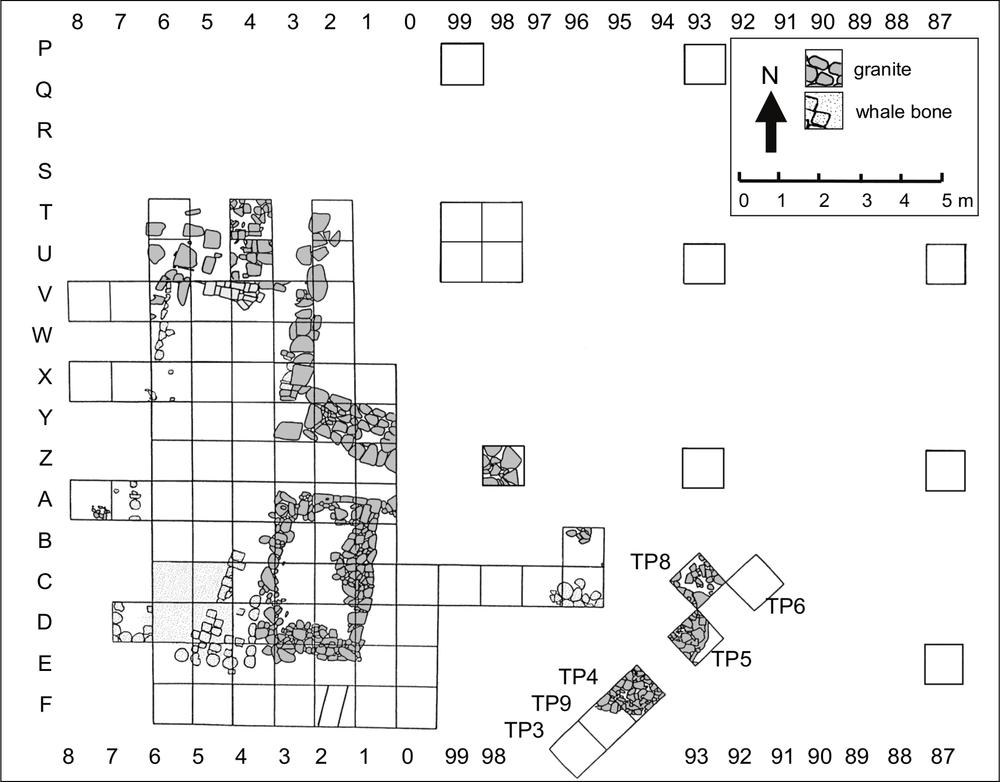

The site was divided into a grid of one meter squares based upon north–south and east–west baselines. These squares also formed the basic unit of excavation, although a combination of open areas, trenches and single test pits was used in different parts of the site. Excavations were undertaken over several seasons, in part dictated by limited funding, seasonal opportunities to attract volunteers and permit constraints on clearance.

Excavation proceeded with arbitrary spits of 5 cm unless natural stratigraphy was detected. Artefacts were plotted in situ where visible, with deposit also sieved through screens of 5 mm or smaller. Bulk samples which were later sieved through a 2 mm mesh confirmed that, other than small, undiagnostic bone fragments and the very occasional pin or small glass bead, most material had been recovered through the larger mesh. All artefacts were bagged for sorting and analysis upon return to the laboratory. Aside from representative samples, all loose structural materials including brick, stone and whalebone remained at the site.

The area being excavated expanded as the form of the main structure, not visible from the surface, was progressively revealed. The logical starting point for the first season in November 1989 was a re–excavation of the area uncovered in 1987, extending the pits slightly beyond and below the disturbed zone. The fragile nature of the whale vertebrae floor surfaces meant that particular care had to be taken. In some areas it was decided to excavate down to within several centimetres of the floor, probe to confirm the presence of the surface, but not uncover the surface. Those areas of whale bone are shown on Figure 5.4 as stippling.

Over the next two seasons the excavation area progressively extended to uncover the whole of Structure One, including the foundation of a fireplace at the northern end and low stone walling along the eastern edges. The whalebone surface did not extend across the whole floor area, although it did continue to edge some areas (described further below).

A stone flagged path was discovered leading from the eastern doorway, heading southeast. This proved to connect Structure One to a small second building, also with a whale vertebrae floor (Structure Two). There was insufficient time to excavate this building, although test pits established its dimensions.

In addition to the main building excavations, a line of small test pits was also extended westward towards the beach (not shown in Figure 5.5). Within a several meters of the western edge of Structure One it was clear that although some artefacts were present, the deposits had been substantially re–worked by storm action.

Test pits were also excavated to the east of Structure One and the remnant dune it sat on, through what was then a grassed picnic area. This had originally been avoided on the incorrect assumption that the vegetation clearance and levelling by machines would have removed any deposit, such as encountered at several other whaling station sites. A test–pit excavated in square U98 at the start of the 1989 season had revealed a high density of bone and artefacts within the first ten centimetres, after which the pit was backfilled and attention given to the main structural features. In the final weeks of 1991 and with a temporary surplus of volunteers, the square was finally fully excavated. The continued high density of bone to a depth of twenty centimetres and the presence of a possible posthole led to the opening of several adjoining squares to determine if the latter was evidence of a wooden structure or fence line. While no further postholes or structural features were found, a similar density of material was encountered in squares T98, T99 and U99. It is possible that the excavation of a wider area to the south may reveal other postholes.

It was decided to sample more widely in this grassed area, with squares opened at Z93 and U93. These pits revealed from 20 cm to 30 cm of relatively undisturbed ash and bone deposit which strongly suggested that this was the sought–after refuse area for the whaling station. With time running out and an already appreciable volume of material for analysis, an attempt was made to determine how far the deposit extended. This resulted in the excavation of squares P99, P93, U87, Z87 and E87, all of which also contained what was obviously domestic refuse and dietary remains to depths of between 30 cm 72and 70 cm. The area further north of this was the car park and could not be disturbed. At this point, having excavated a total of 105 meter squares, it was decided that more than sufficient material had been recovered to address the questions.

STRATIGRAPHY

Although there were common elements in the stratigraphic sequences across the site (summarised below), the excavated areas can be divided into five main zones. A longer description is available in Gibbs 1996, while only samples of the stratigraphic sections are provided here for illustration.

Structure One

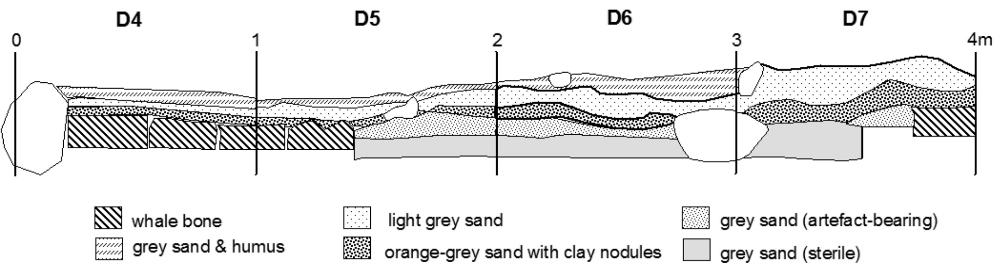

In broad terms, the stratigraphy within the walls of the larger of the two structures can be divided into five major units. The upper layer was composed of organic–rich brown sand (10YR 4/3) with heavy root penetration and modern artefacts. Immediately beneath this was a lighter grey/white sand layer in which the first 19th century artefacts appeared, increasing in density with depth (Figure 5.6)

The occupation surface of the building (if not the floor surface) was probably indicated by a 5 cm to 10 cm layer of orange–tinged sand (7.5 YR 6/8, but varying), mixed with small nodules of clay which could possibly be deteriorated brick, occasional fragments of charcoal and shell, and some artefacts. The thickness and consistency of this layer varied over the total area. The lack of compaction suggests that this was not the floor itself, although the upper surface was roughly level with the top of the whalebone vertebrae seen around the edges of the wall, and particularly in the southern portion of the hut. Further discussion of floor surfaces is provided below.

Figure 5.5 Plan of Excavated Features at Cheyne Beach.73

Figure 5.6 Stratigraphic Profile - Squares D4–D7 (east to west across floor of Structure One).

Beneath the under–floor layer was a dark grey sand unit (7.5YR 3/0) with a sharply decreasing density of artefacts, which in turn overlay a sterile unit of lighter grey sand (2.5YR 3/0). The break between these two layers was not always clear, and was often indicated simply by the absence of cultural material. There were minor variations to this sequence, including some modern disturbance and intrusive pits.

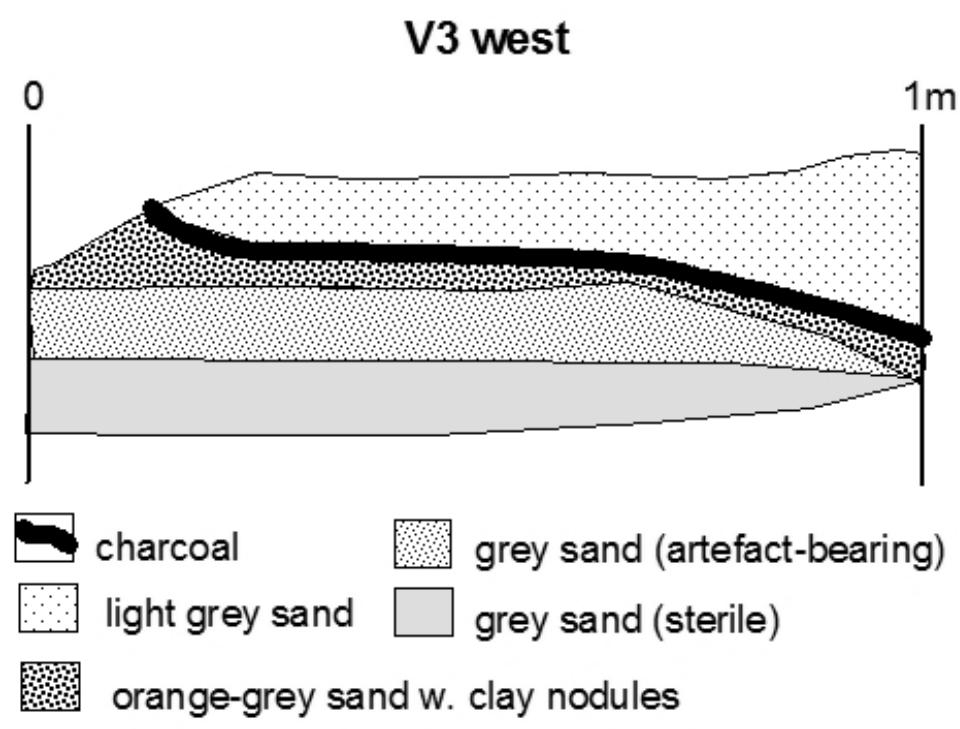

Figure 5.7 Stratigraphic Profile – Square V3 (west face) adjacent to fireplace in Structure One.

Rabbit warrens penetrated the sections in C6 (west) and A6 (west and north), but were confined to the sterile lower layer. Directly above the probable floor level around the east side of the fireplace was a 2 cm layer of ash and charcoal (Figure 5.5). As the usual lighter grey/white sand continued above this layer it was potentially an early deposit, although it may represent either a cleaning out of the fireplace, or even a small campfire after the removal of the floorboards and the end of the use of the building as a whaling station. The remains of a whole smashed (19th century) bottle just above the floor level in square B2 was presumably from a similar post–occupation event.

During the 1987 National Trust survey (MacIlroy 1987) a continuous shovel pit had been dug around the stone–walled section in the southeast corner of the structure. This roughly fell within the boundaries of squares A1 to A4, B1, B4, C1, C4, D1, D4 to D6 and E1 to E6, with the latter two areas including a two by two meter section of whale bone floor surface. Although this trench was partially backfilled, a 10–15 cm overburden of spoil remained mounded over squares A5, A6, B5, B6, C5, C6 and D6. This contained some artefact material which was removed as overburden but also sieved and retained for analysis.

Western and Southern edge (ext. Structure One)

The stratigraphy in the test pits along the western and southern edges of the grid but external to Structure One ((A8, X7–8, V7–8) roughly corresponds to the upper layers seen within Structure 1, with an organic rich surface with heavy root penetration giving way to light grey (possibly wind–deposited) sands. A darker grey unit containing a low density of artefacts underlay this, giving way to grey–white sterile sands. There were several areas with variations to the stratigraphic sequence or higher density deposits. For instance, on the western side of Structure One, Square A8 included a surface of orange–tinged sand (5Y 4/1) mixed with clay/brick fragments and small stones. This layer, sloping gently downward to the west, may have indicated a pathway from a door (in the unexcavated square B7, running to the beach.

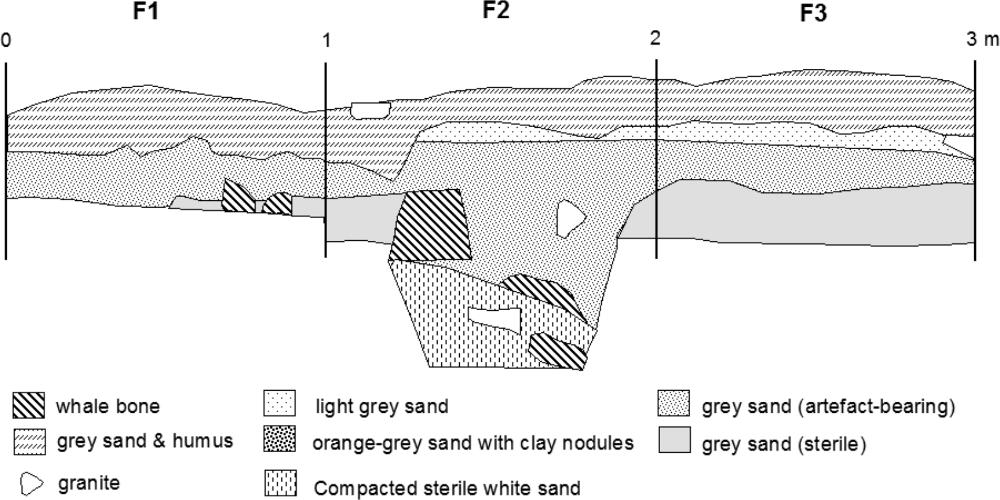

The trench in square F2 is approximately 65 cm wide, roughly aligned with the east wall of Structure One. Unfortunately the 1987 shovel trench passed through the adjacent E squares, obscuring the possible relationship with the structure. It was clearly contemporary with the occupation of the station, cutting through the sterile grey sand unit and with the upper two thirds filled with occupation debris which the artefacts suggest was from one episode. The lower third, (to 55 cm depth or 85 cm below current surface), was filled with compacted white sand (Figure 5.11).

The trench visible in the wall of square D0 and along the southern edge of C0 is 75 cm wide and less well defined than the F2 feature. The trench was excavated to a depth of 20 cm, (50 cm below the current surface) but no artefacts were recovered. The 1987 shovel trench also obscured the relationship between this features and the adjacent structure.74

Figure 5.8 Stratigraphic Profile - Squares D4–D7 (across floor of Structure One)

Structure Two

The interior of Structure Two was encountered in two squares, TP5 and C96. The latter square provided less than 5 cm of vegetable matting and organic–rich grey sands over a whalebone floor surface. While TP5 intersected a stone wall, it was still possible to examine a small area of internal deposit in the western corner of the square. This contained the dark grey topsoil, underlain by a gritty orange sand/clay mix seen in both the interior and exterior portions of the square, which was probably a mortar associated with the rubble. At the base of this unit was a layer of charcoal and ash which contained artefacts, including a nearly complete clay tobacco pipe, supporting the working hypothesis that this was originally the hearth. Excavation did not continue below this level.

Midden Area

As noted, the area east of Structure One and north of Structure Two was originally avoided as it was thought that to have been disturbed. However, while some intrusions are evident, it would appear that this area retains a high level of stratigraphic integrity.

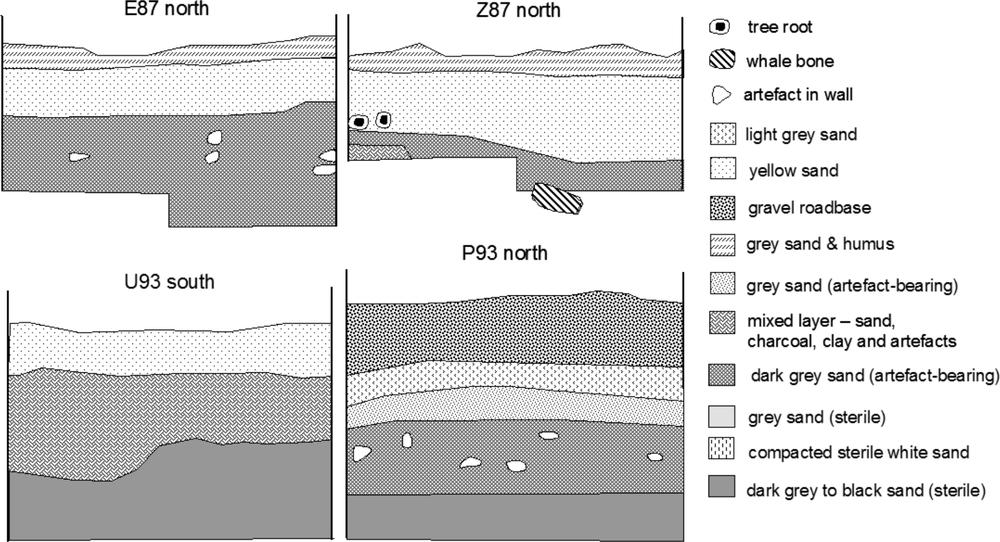

A simple three unit stratigraphy extended from the eastern wall of Structure One to at least T98 and U98. The upper layer of between 5 cm and 10 cm was the organic–rich light–grey sand which covers the rest of the site, heavily penetrated by roots and containing modern artefacts reflecting the use of the area by recreational fishermen and campers. Immediately below this another 10 cm band, were the grey sediments containing a dense layer of 19th century material, with the density of bone increasing to the east. Another break then occurred with a change to a sterile light–grey sand layer (Figure 5.7).

The squares to the east and north of this area proved to have a markedly different stratigraphic profile. Square U93, four meters east of the earlier squares, contained a 30 cm layer of archaeological deposit beneath the upper grassed layer. The artefact–bearing unit was composed of faunal material intermixed with charcoal, a limited amount of metal and other materials. Only small quantities of the bone are actually burnt, suggesting that the ash may have been a secondary deposit, perhaps emptied from a hearth, rather than the result of a fire in situ. A dark grey, almost black sterile layer underlay this, damp with the feel (and smell) of a peaty swamp. The same basic sequence is repeated throughout the seven squares between P99 and E87. It would appear that the artefacts seen throughout this area were originally discarded into a natural depression behind the foredune, similar to that seen to the southeast (Figures 5.8–5.10).

Squares P99 and P93 fell along the southern edge of the gravelled car park area, with the top 20 cm and 30 cm respectively of each pit being dolerite roadbase fill. Immediately below this was the grey artefact–bearing sand with a density of bone comparable to the other pits, followed by the very dark grey or black 'swampy' unit which, while mostly sterile, had some artefact penetration to a depth of 10 cm. It is not known how much of the original upper deposit had been removed by grading or preparation of the car park, although comparison with the adjacent squares suggests it may have been more than half of the artefact–bearing unit (Figure 5.7).

Squares TP3 and TP9 formed a two by one meter trench from the southeast corner of Structure Two (Figure 5.11). Beneath the humic layer was a 10 cm to 30 cm artefact–bearing unit of grey sand with high clay content, unlike that seen in F0, but similar to TP6 on the northeast side of the Structure Two. As for the pits to the north of Structure Two, it would appear that artefacts were discarded into a natural depression which has also subsequently filled with sand and sediment, but remains lower than the level of the building. 75

Figure 5.9 Stratigraphic Profiles – E87 north, Z87 north, U93 south, P93 north

Figure 5.9 Section E87 (south wall).

Summary of Stratigraphic Units

With minor variations, the stratigraphic sequence is vegetation above organic sands, underlain by loose grey sands which postdate the occupation of the site. An artefact bearing layer sits below this, which in the case of the structures included a floor–level indicator of orange clay mixed with sand and/or whalebone. Artefact density decreased below this to a sterile layer which varied from white beach sands to black peaty sands.

The squares excavated on the east side of the site contained the greatest depth of cultural deposit, with some layering evident within the artefact–bearing unit. However, it has not proved possible to make an inter–pit correlation of these finer divisions, either on a purely stratigraphic basis, or through the use of diagnostic artefacts.

Figure 5.10 Section Z93 (west wall).

Even within the individual pits the manufactured artefacts mixed in with the primarily faunal deposits do not provide an indication of either the ages of particular units, or the rate of deposition in general. Artefact mobility through the often loose beach sands, slippage down dune slopes, and reworking by storm action are other factors at work in various parts of the site which make stratigraphic relationships and dating difficult. Possible temporal indicators in the artefact assemblage are discussed in a later section.

BUILDINGS AND STRUCTURES

Structure One is comprised of two components: the main or western section which has an internal measurement of approximately 9.5 m by 3.5 m (approximately 31 feet by 7612 feet) and the eastern section which is 2.5 m by 3.0 m (approximately 8 feet by 10 feet). This provides a total floor area of approximately 41 m2. A plan of the excavated features is shown in Figure 5.2.

The construction of the walls of Structure One is still uncertain, although it appears probable that they were wooden. The large, unmortared stones along the edges are more suggestive of retaining walls to allow the floor to be built up level, rather than being the lowest course of a whole wall. The several fragments of whalebone floor which survive in this section are level with the tops of these boulders, providing further support for this interpretation. The walls around the southeastern section of Structure One use smaller field stones in several layers rising up to half a meter in height. However, this still seems to be a retaining wall rather than the base for a more substantial wall. The difference in style suggests this may have been an extension to the original cottage.

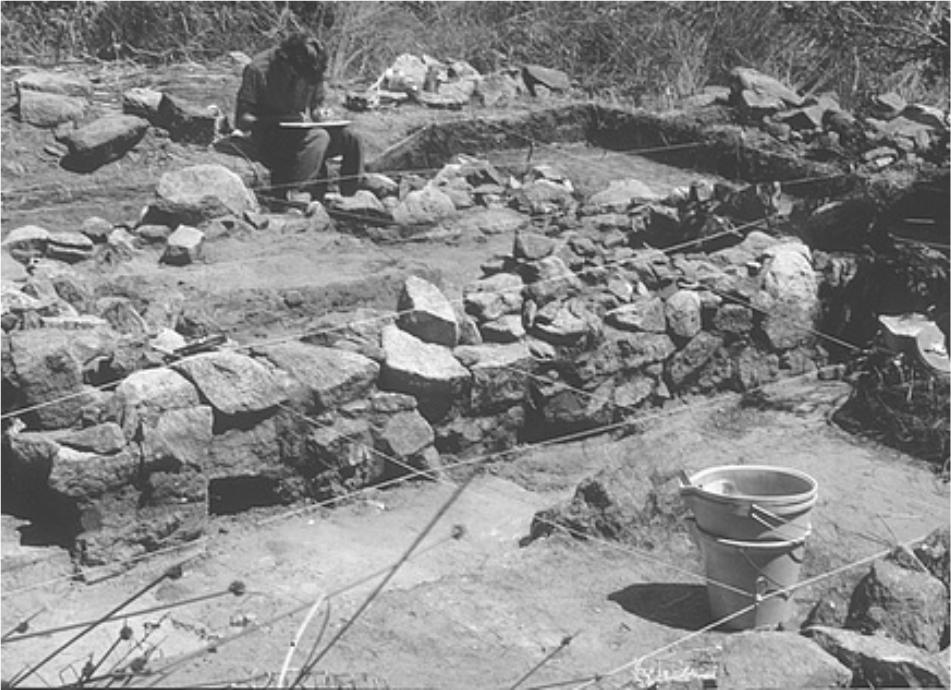

Figure 5.11 View looking north–west over Structure One (Fireplace to rear and stone pathway in foreground).

Figure 5.12 Walls in South–east corner of Structure One.

Unfortunately, no further indicators of a timber structure such as postholes or footings for wooden slabs were identified. The stump of a single wooden post was found at the edge of the whalebone floor at the juncture of squares E4 and E5 and may be a structural timber.

The hearth at the northern end of the cottage appears to have been primarily constructed out of stone, although the large quantity of orange clay spread over the upper layer suggests that low fired brick might also have been used. The flagstones across the front of the hearth would suggest a width of as much as 1.5 m. Although the excavations did not extend to the north side of the hearth, the ground surface shows a spill of stone rubble from the chimney extending for several meters. The ground level slopes slightly downward to the north, and it is apparent that the level of the chimney base had been built up slightly to compensate for this.

Figure 5.13 Fireplace in Structure One (looking north).

Other than being used in the fireplace, it is uncertain what role bricks played in the construction of either Structure One or Two. No whole bricks were found on the site, although badly deteriorated fragments of varying size were recovered. In particular, the layer which is presumed to have marked the floor surface (or immediate underfloor surface) of the cottage often appeared to contain clay and small brick fragments. The nature of the bricks recovered from Cheyne Beach is discussed in the analysis of structural artefacts.

Interpretation of Structure Two is based on a far more limited sample. It is argued that squares C96 and C97 intersected the northwest corner of the building, encountering a surface of whale vertebrae, but once again with no evidence of a surrounding stone wall. The stone pathway also terminates on the northern edge of B96, presumably indicating the position of the doorway. Test pits 3, 4 and 8 intersected stone rubble with ash, interpreted as a hearth at the east end of the building. The probable dimensions of the floor of Structure Two are approximately 3.5 m by 2.5 m, giving an area of about nine square meters.

Perhaps the most interesting feature of both buildings was the use of whale vertebrae as a flooring material. The initial excavations over the southern end of Structure One showed that whole vertebrae had been trimmed and laid with their circular surfaces upwards along what was probably the edge of the wall. This wall edging continued to the northern end of the cottage, although in the northern half of the building the vertebrae had been cut in half. Several traces of bone were also found along the 77northeast wall. Also in the southeastern corner the floor had apparently been carefully paved with vertebrae cut in half and with the rectangular cut surface laid upwards (Plate 5.4 vertebrae floor). This extended only for several meters along the southeast corner, and had been heavily disturbed by the 1987 shovel pit. No whale bones were found in the southeastern section.

Figure 5.14 Whale Vertebrae floor in Structure One (looking north). Note wooden post in right foreground.

Figure 5.15 Whale Vertebrae Flooring in southwest corner of Structure One (looking west over Square D7).

There are two possible interpretations for the whale bone surface. The first is that it may have been intended as a floor, although if so this project was then abandoned after only the southern section had been completed. The second is that the edging was to assist in supporting a wooden floor, either directly, or as bearers for joists. As described previously, the top of the whale vertebrae are contiguous with the compacted nodule clay and sand level which covers the rest of the interior. It should be noted that even with its clay component, this loose matrix would have provided a poor floor surface, suggesting some form of covering. The single 24cm wide section of jarrah board (located in the northeast corner) which may represent a surviving floorboard rests directly upon this layer. However, the roughly north to south orientation (i.e. along the length of the building), may lend weight to the idea that it originally rested on joists running east to west across the floor. However, if the whale bone edging was simply used as bearers, there would be no need for the almost continuous, carefully cut line which extends the length of the west side, or the more extensive coverage along the southern end, features which are suggestive of a decorative function.

Although only a small section at the western end of Structure Two was excavated, it appears that a similar whale bone surface continues across its floor, rather than just along the edge. Although some pieces had been trimmed, the vertebrae were placed with the articular surface upwards. No whale bones were detected in the limited excavation at the eastern end of the building, although it is possible that this did not penetrate beneath the rubble of the hearth. A single trimmed 'brick' of whale bone (15 cm x 8 cm x 6 cm), possibly from a vertebra, was also recovered from square U98. A hole, presumably for a spike, passes unevenly through the brick, although it’s possible function remains undetermined.

While the issue of the function of the whale bones in Structure One remains unresolved, it should be noted that whale vertebrae have been used for structural purposes at other early whaling station sites, both in Western Australia and elsewhere. Local informants at Busselton reported that the buildings at Castle Rock had whale bone floor surfaces which were destroyed when the site was graded in the 1970s. Several sections of this bone now survive in the Busselton Museum. During his excavation of the Thistle Island whaling station in South Australia, McCarthy (1993) encountered four whale vertebrae deliberately sunk into the floor of one of the former cottages, which he interpreted as being associated with supporting a timber floor. In the sites of houses at the 17th century Dutch whaling stations at Smeerenburg (Greenland), whale vertebrae and ribs have also been found supporting floors and the bases of hearths (Hacquebord 1981).

Artefacts associated with architecture, construction, fittings and furnishing are described in the 'household/structural' artefact category, discussed in the following chapter.