CHAPTER 4

WHALING STATION LOCATION AND ORGANISATION

The historical documentary record contains limited information on the physical and operational aspects of shore whaling in Western Australia. With few written descriptions of the actual location or organisation of the stations, or the nature of life and labour at these camps, it was felt that the archaeological record could make significant contributions to our understanding of the industry. The following chapter focuses on the nature of the Western Australian shore whaling stations, exploring patterns of site selection, use and abandonment, and determining the organisation and nature of the different site elements which comprised the stations. It also examines evidence for changes in locations and organisation over time. Comprehensive histories of individual stations are provided in Appendix A.

SITE SELECTION

At the time of the original study on which this volume is based there were few archaeological reports available on other Australasian shore whaling sites. An initial model of what might be expected of the location and organisation of a shore stations was drawn from several historical studies of Australasian whaling, including Dakin (1938:33), Little (1969:114), Morton (1982) and Pearson (1985:3):

- sheltered bay or beach.

- tryworks near the shoreline, usually covered by an open sided shelter or partially enclosed shed.

- ramp or shelving beach on which to haul the blubber up to the tryworks, sometimes with one or more capstans, winches or shearlegs.

- additional buildings such as a cooperage, and storehouse(s) for gear and oil.

- huts for the men, a cookhouse and gardens for food.

- watchtower or natural elevated look–out within audible hailing or visual range for signaling.

In more elaborate establishments there might be one or more jetties, a boat shed, ramps for hauling up boats, oil storage sheds or other facilities.

In the 1840s Charles Enderby, a noted British whaleship owner, suggested several other criteria for those considering establishing a shore station in New Zealand:

a temperate to cool climate (to lessen leakage from the wooden casks); a reasonable distance from settlements from which plunderers might come; plentiful wood and water; good soil for gardens and pasturage for cattle; easy sailing distance from a supply base; a reasonably nearby source of recruits; and most important of all, a good harbour (Morton 1982:229).

Later archaeological studies have suggested various other factors and elements (Lawrence and Staniforth 1998; Prickett 2002; Nash 2003; Lawrence 2006), which will be discussed further below.

One of the most important factors in site location was presumably that a station was situated along the migration routes of the whales, preferably within bays known to be regularly frequented by the feeding or calving animals. Explorations of the Western Australian coast prior to permanent settlement, as well as the flurry of investigations by colonists searching for new harbours, rivers and fertile lands, saw whales reported in various bays on both coasts.

Great numbers of fish [whales] are annually seen off Rottnest Island, and some come into Gage's Roads: Geographe and Augusta Bays are very superior stations; King George's Sound, Two People Bay, Many [Doubtful] Island Bay (not laid down in the charts), are good harbours and full of fish; and by the report of Capt. Pace, Shark's Bay is also a good station and harbour (Anon 1836:21).

Over the next several years the success of these and other bays as safe anchorages and good locations for whaling was proved by the increasing activities of American and French whaling vessels. Ogle's (1839:244) promotional report on the state of the Western Australian colonies even acknowledged the extensive contributions of the Americans, reproducing their sailing directions and stating that ‘we are more indebted to them than to any others for our knowledge of the inlets and anchorages of the western seaboard’. The same situation clearly applied to the south coast as well (Garden 1977).

While the physical characteristics of what were judged to be desirable or at least suitable locations for shore whaling stations are discussed in a later section, the processes of selecting which locations to use, particularly in the first several seasons, can be considered here. Despite the inexperience of crews described earlier, presumably the headsmen or managers of prospective fisheries had some prior experience. Selection of a suitable location and the organisation of the station and the party would therefore have depended upon their breadth of knowledge and their ability to adapt this to the economic constraints and environmental conditions of the colonies. At least one of the colonists, Thomas Hunt (who became chief headsman of the Northern Fishing Company), had worked in the North American shore whaling industry being ‘for some time the superintendent of a fishery at Cape Cod’ (PG 3/9/1836). However, others 56may have drawn upon experience in the pelagic industry, or taken advice from visiting British or American pelagic whalers.

On the west coast the initial decisions on which locations to use were circumscribed in part by the limited number of suitable bays. Although Bathers Beach and Carnac Island both proved in later years to be quite good stations, their selection for the 1837 season reflects their close proximity to the major settlement at Fremantle. In contrast, on the south coast, which contains a far greater number of apparently suitable locations, the first stations were established at Doubtful Island Bay, over 160 km from the nearest European settlement at Albany. Given the considerable cost and effort required to move people, plant and supplies such a distance, particularly in the early phase of the settlement, the owners must have perceived the location as particularly desirable, or been advised as such.

During the 1830s and 1840s there appears to have been a strong correlation between the use of particular bays by foreign pelagic whalers and their subsequent occupation, usually within several years, by colonial shore whalers. On the west coast Safety Bay, Koombana Bay (Bunbury) and Castle Rock were all known haunts of American whalers. On the south coast Frenchman's Bay, Two People Bay, Cheyne Beach, Cape Riche and Doubtful Island Bay are known to have been successfully used by American and French whaling vessels (Gibbs 2000). More distant areas such as the Dampier Archipelago and Recherché Archipelago were frequented by foreign whalers in the early settlement period, but were not occupied by the colonial whalers until the later phase of the industry.

The predictable result of this pattern of occupying 'proven' locations was a series of conflicts as the colonials established their shore camps and attempted to assert their territorial rights by demanding that the foreign whaleships depart those areas. Chapter Two has already described how the Americans were well aware of their role in the coastal exploration of the region and the government's inability to enforce any restrictions (CSR 85/82: 24/1/1840; Gibbs 2000). However, they generally yielded by departing or offering to join in partnership with the local group.

As suggested previously, during the 1840s the initial formation of whaling parties was often the result of local entrepreneurs in each area establishing their operations in the nearest suitable bays. Due to restriction on the expansion of settlement, until the 1850s west coast whaling activity did not move far north of Fremantle. By this period the west coast whaling industry was increasingly under the control of merchants and other persons with maritime interests, so that the extension of the coastal trade network to the new settlements (such as Port Gregory and Roebourne) also made it economical to transport their own whaling parties to these regions (Bain 1975).

Despite the initial use of the remote Doubtful Island Bay location in 1836–37, the re–emergence of whaling along the south coast during the 1840s saw the occupation of bays in and around King George Sound, within a 50 km radius of Albany. Although Albany remained the only major settlement throughout the study period, by the 1860s several small pastoral groups had moved to the eastern coastal areas. For instance, in 1863 the Dempster family established a pastoral station close to what would later become the town site of Esperance. The initial movement of whalers into the Cape Arid (‘East Coast’) region dates to the same period and there is historical evidence of trade agreements between whalers and settlers (Erikson 1978). As on the west coast, the expansion of the coastal trade network into the more distant areas possibly allowed the owners of the whaling parties to offset the costs of transporting and servicing their crews against their trade interests with these small settlements. It should also be considered that by the 1860s there were also more vessels available along both coasts, which must have resulted in a general reduction in the costs of hiring a schooner.

There are at least two instances where highly regarded locations were never used for whaling. The first of these was Shark Bay, glowingly described as a potential fishery by the French explorer Baudin in 1803 (Cornell 1974: 512). In September 1834 a colonial survey party aboard the schooner Monkey also reported ‘innumerable’ black whales and good anchorages on the east side of Dirk Hartog Island, suggesting its potential as a fishery (PG 3/9/1836). Despite this information and later American use of the area (e.g. PG 20/11/1857), Shark Bay was never occupied as a base for colonial whaling, being by–passed in the 1870s for the Dampier Archipelago, near the new Roebourne settlement.

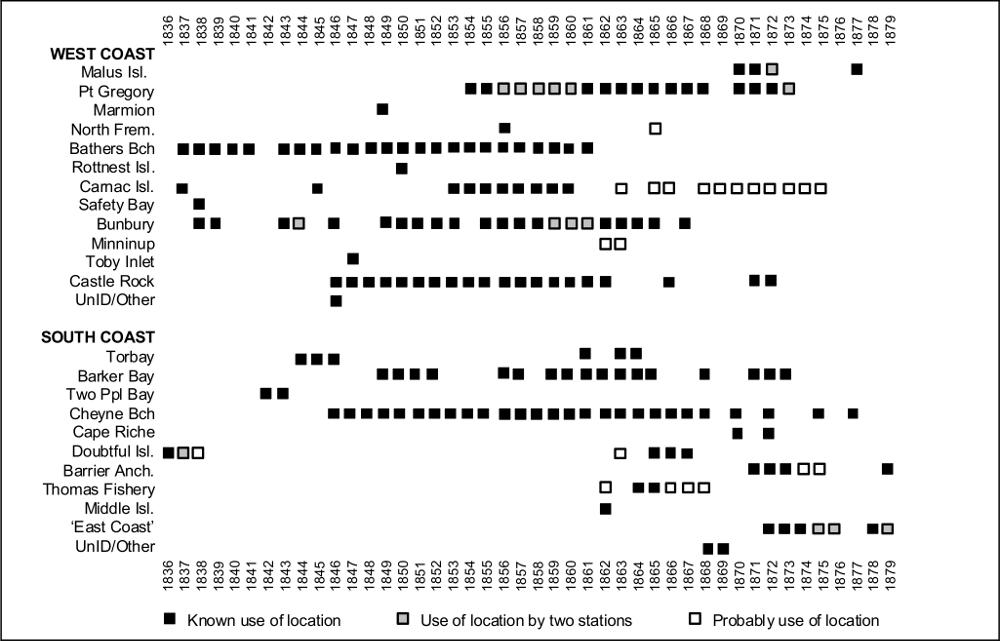

A similar situation occurred at Flinders Bay, on which the small settlement of Augusta was established in 1830. There are numerous reports of the successes of American and eastern Australian whalers in the bay (Inq 3/8/1842; Anon 1843; Hasluck 1955), yet colonial whalers did not come south of Cape Leeuwin or west of Torbay to use the location. Trade with Augusta was irregular and limited by the size of the population, while the rounding of the capes was acknowledged as a difficult passage. Transport would have been expensive for any west coast party, making it simpler to remain in Geographe Bay. For the Albany–based settlers, Flinders Bay was 300 km west of King George Sound and in the opposite direction to the spread of south coast settlement, making it impractical to use the area. Figure 4.5 illustrates the pattern of use and abandonment of west and south coast locations by the whaling parties.

While some factors associated with the initial occupation of locations such as proximity to settlements and proven use by foreign whalers have already been described, the reasons for abandonment often remain elusive. On the west coast it might be supposed that the limited number of bays encouraged the re–use of the same locations for extended periods. The historical record suggests that the several locations which were only used for a single season (Marmion, North Fremantle, Safety Bay, Toby Inlet) were selected because the more suitable 57positions in those areas were already occupied (Appendix A and B1). These sites lack many of the physical characteristics of the usual locations, especially a sheltered harbour, and may have proved too exposed and difficult to use as a base. It is also possible that sites closest to growing towns such as Fremantle and Bunbury may also have been forced to close in the 1860s because of objections to smell.

On the south coast the early abandonment of Torbay and Two People Bay was simply a result of the limited size of the local whaling industry. With the two parties operating between the mid–1840s and the mid–1860s occupying well–established bases at Cheyne Beach and Barker Bay, these other locations went unused. Their re–occupation came in the later period of whaling activity with the emergence of the split season and the move towards using two or more widely separated locations. The sites around King George Sound became the bases for the early season, with the new locations on the 'East Coast' around Cape Arid used in the later part of the year. Unfortunately, there is usually no specific documentary record of which late and early season locations were being used, particularly in the final phase of the industry.

Figure 4.1 Timelines of shore station occupation

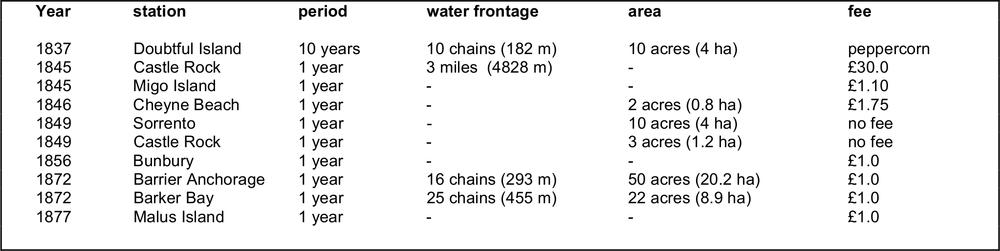

Table 4.2 Whaling Station Lease Fees

58Lease Agreements and the Occupation of Land

Aside from the physical and logistical considerations in selecting suitable locations for whaling stations, the occupation of particular sites and the development of infrastructure was constrained by the system of leases regulating the use of the coastal lands. With the Crown retaining ownership of foreshores and much of the hinterland, especially the harbour areas favoured by the whalers, it was necessary for the owners or managers of the stations to secure a lease for the land on which their station would be constructed. A number of lease requests, agreements, or at least fragments of information regarding land tenure were located during the course of this research, allowing some insight into how the system operated.

In general, leases were negotiated on an annual basis, usually some time before the commencement of the season. There were, however, instances during the early phase of the industry where the government was willing to allow quite lengthy leases of land for whaling purposes. For example, a section of Doubtful Island Bay was leased to John McKail for ten years (CSR 52/133:1836). Bathers Beach and Carnac were under either five or seven year leases, depending upon which reports are followed (SRG 11/5/1837; SRG 29/6/1837; PG 24/3/1838). This may reflect the early enthusiasm and anticipation of development into a major industry. There are also isolated cases of long leases being offered in later periods, such as the Barker Bay station being granted for a term of seven years (CSR 189/247: 12/9/1849).

The fees paid for the lease of the whaling stations were generally quite low (Table 4.2) and were sometimes waived completely in special circumstances. Correspondence for Barrier Anchorage, Barker Bay and Bunbury suggests that charges remained consistent from year to year, although there were some variations. For instance, in 1845 the government originally set the lease of the Migo Island anchorage at £5, although after several months of negotiation the license records a sum of only £1.10s being paid. It should be noted that the high fee (£30) charged for Castle Rock in 1845 included a substantial section of coast and hinterland.

Whaling station leases performed two functions. The first and ostensibly only reason was to get formal permission to erect the station buildings. In cases where large areas or adjacent islands were included in the arrangements, the stated aim was to run sheep or cattle for the use of the station. However, the second, ulterior reason for taking a lease was to exclude other whaling parties from using that beach, either for their camp or as a landing place for boats or whales. This was the probable concern of Viveash at Castle Rock in 1845, with his attempt to secure several miles of beach frontage possibly associated with a desire to force Hurford and Penney's rival party out of the area (CSR 140/107: 20/9/1845). In 1872 Hugh McKenzie's challenge of Thomas Sherratt's right to use the leases in this way resulted in the Commissioner for Crown Lands cancelling all licenses on the south coast (BL Acc. 346: 16/1/1873; Acc. 346: 12/2/1873). Leases do appear to have applied on the west coast for the several remaining years of the industry, with John Bateman obtaining a permit for the Malus Island station in 1877 (SDUR B10/1144C: 12/1/1877).

The leases set a number of conditions upon the users, the first being that the arrangement would be forfeit if either the fee was not paid or the land was not occupied for whaling purposes during the season (CSR 189/247: 12/9/1849). The latter provision was to ensure that land and stations, particularly those granted in long lease agreements, were not needlessly locked out of use. In the case of Bathers Beach it seems that the Fremantle Whaling Company was allowed to sub–lease to other operators, although there were peculiarities in their occupation of the land which may have permitted this situation (see below).

The other significant aspect of the lease agreement was that at the end or cancellation of the license, the government not only regained the land, but also ‘all houses, buildings, wells, fences and appurtenances’ which had been erected (CSR 52/133: 10/2/1837). It was this clause which was the final downfall of the Northern Whaling Company. After deciding to cease operations as a result of the unsuccessful 1837 season, the company attempted to recoup some of its losses by offering its seven year lease of Carnac Island and all improvements at the station back to the government ‘for a reasonable consideration’ (PG 24/3/1838). It was at this time that the lease was produced and the directors shown the clause indicating that upon the dissolution of the company the land and buildings reverted to the Crown anyway. The discovery of the same condition in the Fremantle Whaling Company's lease (PG 28/4/1838) may well explain why that group chose to continue, hoping for at least some future success in the fishery rather than instantly losing its considerable fixed assets by closing.

Later whaling station licenses are less precise and generally do not mention the ownership and removal of the improvements at the completion of the season (CSR 189/247: 12/9/1849; BL Acc.346: 8/5/1872). This may indicate that the government's attitude had eased after the early incidents, letting the companies recover whatever capital they could from the sites. It is also probable that the later, smaller and less well–financed whaling parties would have seen the example of Carnac Island and the general lack of security of the leases as further reason not to over–develop the fixed assets of a station. There were instances where long–term occupation by a single party probably lent some level of security. On the south coast, Cheyne Beach was occupied by John Thomas for at least 22 years, while Thomas Sherratt appears to have used Barker Bay for as long as 24 years. On the west coast, Castle Rock was used by Robert Heppingstone and then his son–in–law George Layman for 14 years.

A variation on the leases was seen at Bunbury and Fremantle, the two 'urban' stations. In these cases not only was the land leased, but also the existing tryworks and barracks buildings, with different parties putting in tenders for their use during the season (CSR 338/204: 4/9/1855). 59

ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY

Environmental background

The wide geographical dispersal of the Western Australian shore whaling stations along both the west and south coast means that the sites are located in areas with markedly different geologies and climatic regimes, particularly during the winter months when whaling took place. The three major environmental zones were:

1. Dampier Archipelago (Pilbara Block) – a collection of islands up to 15 km long and 3 km wide clustered along the west and north sides of the Burrup Peninsula. The archipelago is a drowned landmass ‘characterised by rock platforms and storm boulder beaches interspersed with localised accumulations of sand and silt in the more protected embayments’ (Vinnicombe 1987:2). The area experiences large tidal variations and has warm and dry winters (Woods 1980).

2. Lower west coast - characterised by long, straight sandy beaches with few significant bays or interruptions (Woods 1980). Old limestone dunes have become islands and headlands in some areas, with southwest swells and waves creating crescent–shaped northward opening bays behind these hard points. This varies slightly in the area close to Cape Naturaliste, where the granite of the Leeuwin–Naturaliste Ridge outcrops on the coast, with several small, sandy bays forming in between. The Castle Rock station is situated in one such bay. Tidal range is very small and for the most part the areas behind the headlands are well protected. The region experiences a Dry Mediterranean climate with mild, wet winters.

3. South coast - characterised by large granite outcrops which form mountains, headlands and islands. The action of heavy southwest swells and easterly littoral currents upon these granite hard points has resulted in the formation of numerous crescent–shaped sandy bays opening towards the east (Woods 1980). Tidal variation is generally less than one meter. The climate west of Doubtful Island Bay is characterised as Moderate Mediterranean with wet winters. To the east of this the climate is classified as Dry Mediterranean. On the coastal fringe the cold winds, rain and squalls blowing in from the Southern Ocean during winter can make maritime work difficult.

Archaeological Survey

As noted in Chapter One, several 19th century whaling station sites had been identified during the 1970s and 1980s. The National Trust (W.A.) survey of whaling stations in particular drew on Ian Heppingstone’s historical research to identify 20 probable locations for whaling activity, with MacIlroy’s survey identifying seven sites with structural remains or artefacts (MacIlroy 1987:1). These studies provided a solid basis for the current study, commenced several years later.

Based on a more comprehensive historical analysis, several of the locations suggested in the 1987 study were eliminated as misinterpretations of the historical records (Ten Mile Well, Collie River and Augusta). A total of 21 locations, such as specific bays known to have been used as the site of one or more shore stations, were identified. In addition, further clues were generated as to probable site locations in bays which had previously been surveyed unsuccessfully.

Surveys were undertaken in several stages between 1990 and 1993, with the very limited funding available meaning that the more distant or inaccessible locations could not be visited. Initially the most accessible sites on the west coast between Port Gregory and Castle Rock were surveyed, followed by the south coast sites between Torbay and Cape Riche. Finally, the remote sites of Barrier Anchorage and Thomas Fishery were surveyed. Four locations (Malus Island, Carnac Island, Middle Island and Doubtful Island Bay) could not be visited. For these places it was necessary to speak to local informants and use other sources of information to assess the existence or condition of the sites.

Archaeological remains with a high probability of being associated with the whaling industry were identified at 11 locations and will be discussed below. However, a number of the other locations without visible structural or artefact evidence, or where later development or use had obscured or obliterated evidence, still exhibited topographic and other features which were felt to be relevant to the organisation and operation of the stations.

In many instances the features which had made locations attractive in the 19th century, such as sheltered anchorages, sandy beaches, a water supply, etc, were also attractive to subsequent users. Post–whaling fishing camps, wool sheds, jetties, camping grounds, car parks, boat ramps or other features occupied, often overlay and obscured, if not destroyed, the original whaling station sites. In some respects this re–use became a marker of a potential site, although in many cases the rare surviving whaling stations features had survived through pure chance on the edges of these later disturbances. In several cases the potential for excavation was eliminated by bitumen sealed surfaces or heavy traffic.

Several sites (Port Gregory, Castle Rock, Barker Bay and Cheyne Beach) were test–excavated to determine their archaeological potential. It was intended to excavate one site on each coast and compare the results, but this proved logistically difficult. Cheyne Beach provided the best combination of structural and artefact deposits, and was chosen for detailed investigation (Chapter 5).

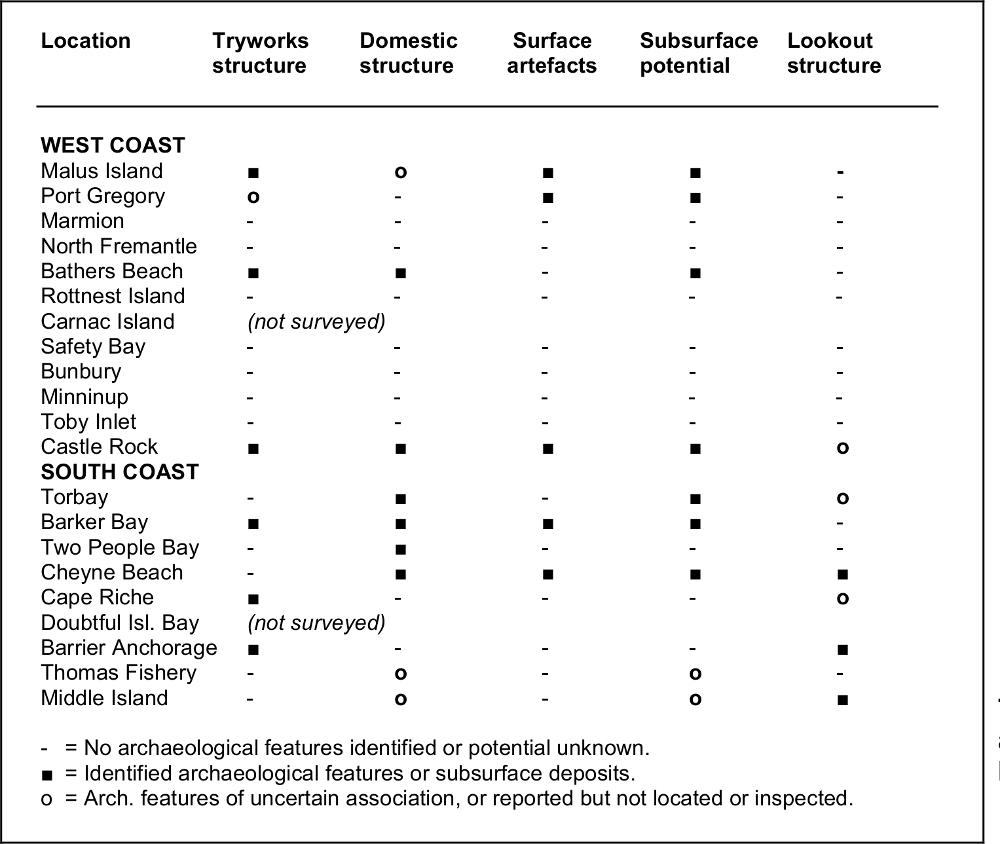

The results of the survey are presented in detail in Appendix A. This includes location and site plans and historical information specific to each station. While the archaeological data have been synthesized in the following discussion, Table 4.3 summarises which features were recorded at each site during the survey. The survey strongly suggests that the determining factors of station location and organisation were closely interrelated. Common characteristics exhibited by the sites are described, as are exceptions or variations from the norm. 60

Table 4.3 Summary of archaeological features located during survey.

Location - Bays and Headlands

The main landscape feature in the location of shore whaling stations is a bay or sheltered section of coast. Along the Western Australian coast these have been formed by the action of swells and currents upon geological hard points, namely granite outcrops on the south coast and limestone on the west (excepting Castle Rock). Immediately behind these hard points or headlands are usually the sheltered sandy coves which were favoured as sites for the whaling stations and are still used as anchorages for small vessels.

Three main possibilities can be advanced for the use of bays for whaling.

1. Humpbacks and right whales are known to visit and sometimes spend lengthy periods in bays and sheltered areas during the course of their migration.

2. The curve of the bay may have allowed the whalers to trap the whales against the shoreline.

3. Bays provide some shelter from the swells, currents and winds of the open sea, both for the whaleboats during the process of hunting and for the station complex during processing of the catch.

The first factor is the most difficult to verify, given that by the time systematic scientific research was undertaken on whales in coastal Australian waters, they were mere relics of the original populations. However, scientific, historical and anecdotal evidence suggests that migrating humpback, right and other whale species do appear to favour particular bays and areas. The use (and non–use) of bays by whales is therefore a potentially significant factor in the use, success and abandonment of particular stations.

The situation of the whaling station at the projecting peak or headland allowed the boats to radiate outwards to intercept whales entering or swimming past the bay. Careful placement of two or three whaleboats would allow the whalers to trap the animals in the curve of the shoreline. However, the initial hunting range of a station using only whaleboats might be roughly defined through the observational limits of the look–out, with or without optical aids. This would naturally include the adjacent ocean, to whatever distance it was felt practical or possible to send the boats in pursuit. Use of a larger vessel such as a schooner as a launching platform and for cutting–in could extend this range considerably.

The final factor takes into consideration that shore whaling in Western Australia was pursued during winter, a season when (with the possible exception of Malus Island) extremely heavy swells, gale force winds and other difficult environmental conditions are the norm, particularly on the south coast. The inner areas of the bays could be expected to afford some protection for the small whaleboats and their crews. With the whaling station on the lee side of the headland the carcass could be drawn into sheltered waters for flensing, the boats could be beached out of the surge of the waves, and the buildings of the camp would not be subjected to the worst of the winds and rains.

Look–outs

A look–outpoint for a shore–based whaling station required two main attributes. The first was that it 61command a wide view of the bay, adjacent seas and if possible neighbouring bays. The second was that the look–out had to be visible from the whaling station, or at least the person stationed there would have had to be able to signal without major difficulty. The normal position for the look–out was atop the headland or high dune which sheltered the station, usually at a distance of no more than several hundred meters. There is some evidence that the Bunbury station used a series of look–outs on high dunes between Casuarina Point and Minninup, 19 km southward, to signal the approach of whales (Lally n.d.; Mitchell 1927).

Another option was to place the look–out on the peak of a nearby island, which appears to have been the case at Torbay (Migo Island), Middle Island (Goose Island) and possibly the small island in Barrier Anchorage. Although there is no specific information to suggest that the Cape Riche party used Cheyne Island as a look–out, Gorman's memoirs (AA 22/8/1929) show that the whalers visited it on occasion. An early survey of the area noted the existence of a 'whaler's look–out' on the southern slope (Gregory 1850), although as this was nearly 20 years before the first recorded use of the bay by colonial whalers, it is possible that it originated from the foreign whalers who had frequented the area during the 1840s. The Bathers Beach (Fremantle) station was even reported as receiving signals from Rottnest, 18 km westward, when whales were sighted near the island (Inq 21/8/1861).

There is limited historical or archaeological evidence of whether particular station lookouts had shelter structures, although some protection would not be unreasonable given their winter usage. The Bunbury station appears to have had a wooden watchtower on Lighthouse Hill, above the town, the timber for which was later used to construct two houses (Barnes 2001:62). However, this is the only evidence for such a construction.

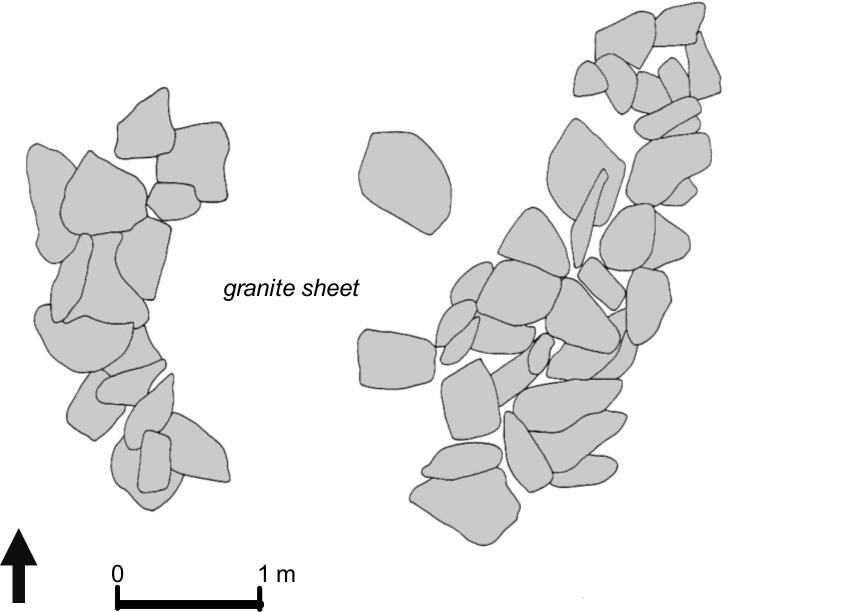

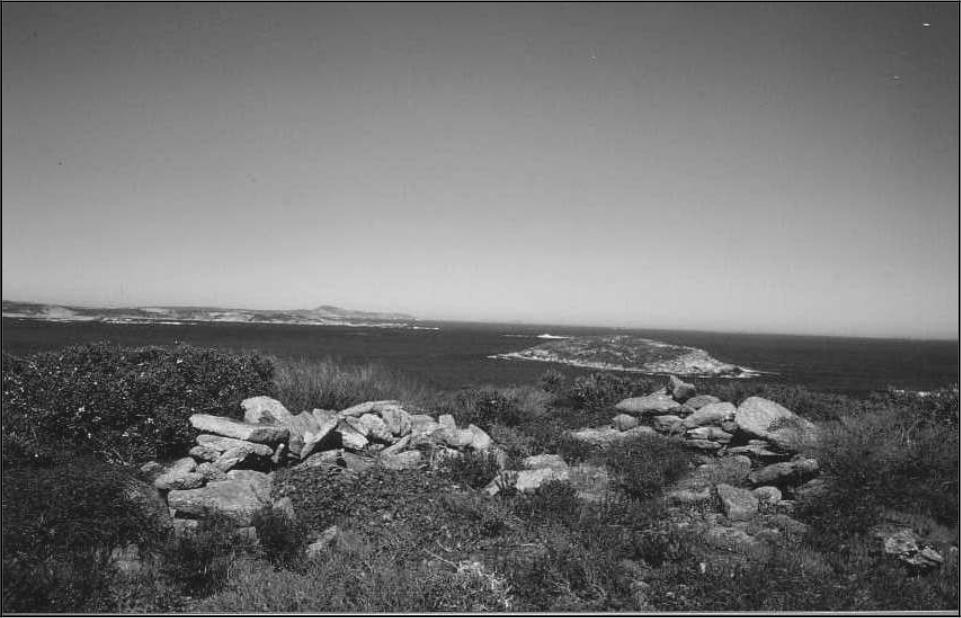

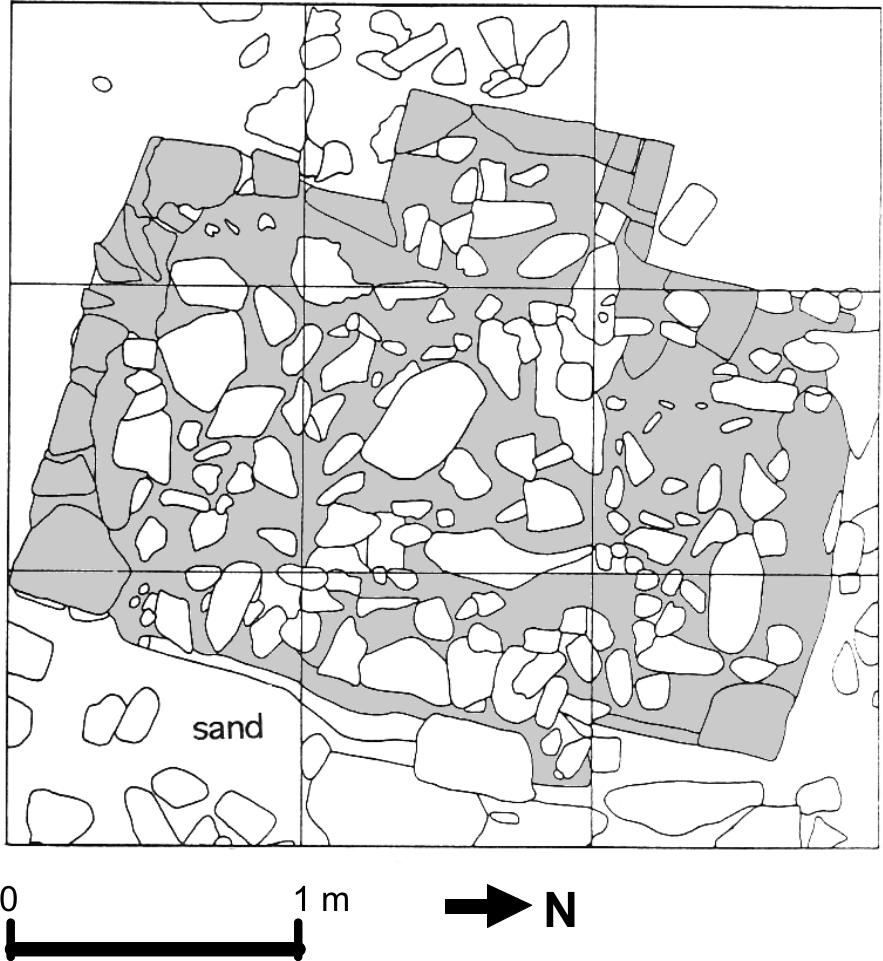

At Barrier Anchorage and on Goose Island (Middle Island) there are low dry–stone walls on the hills above the station (Figure 4.7,4.8; Pearson 1988). Although Cheyne Island (Cape Riche) could not be visited during the survey, there is some historical and oral suggestion that a stone windbreak also survives near its peak. There are oral reports about another structure on the adjacent mainland, although its position could not be pin–pointed. This may be the unidentified low granite wall described as a whaler's look–out in a photograph at the Albany branch of the Western Australian Museum.

Cheyne Beach has a granite boulder on the headland above the station with a small ledge which makes an ideal seat for a person watching out to sea. Unfortunately, the rock is too weathered to determine if this ledge is a natural or artificial feature. Castle Rock also has a 'look–out rock' on a hill nearly 500m east of the station, but still within direct line of sight. There were formerly several stone walls and small buildings on the cliff above Bathers Beach which would have served to shelter the spotter for the station (Bavin and Gibbs 1988).

Figures 4.7 Barrier Anchorage Look–out.

Figures 4.8 Barrier Anchorage Look–out.

The dry-stone walls of the south coast look-outs are a meter or less in height, and were probably meant as windbreaks behind which the look–out could crouch to avoid the worst of the icy gales off the Southern Ocean (Figure 4.7). It is possible that wood and canvas structures were used to provide a roof or upper sides, although there is no evidence for this. On the west coast the much more moderate winter conditions made protection of this kind less important.

There is only a limited mention of signaling methods for alerting the station and directing the whaleboats. In many instances a strong pair of lungs and the cry of ‘whale–ho’ (Mitchell 1927), ‘blow’ (McKail 1927), or the well–known ‘there she blows’ (PG 19/7/1850) would be enough to rouse the men. It is less certain how more distant points transmitted their message, although it is possible that horns, guns, or even small charges may have been used. Oral information collected by Lally (n.d.:55) states that in the Bunbury area the spotter on the sand dunes had ‘a high flagpole next to him, with a specific number of flags, and armed with a telescope’. The signals received at Bathers Beach from Rottnest may well have been broadcast by flags, smoke, or heliograph (mirror flashes) (Inq 21/8/1861), which later became a favoured means of communication from the island (Moynihan 1988). 62

Flensing areas

A popular misconception, fostered by observations of modern whaling facilities, is that the whale carcass was hauled out of the water and onto some form of deck or ledge for flensing. Images from other parts of Australasia, as well as the archaeological evidence from the Western Australian sites suggests that carcasses were beached in the shallows and secured by ropes or chains. The blanket pieces would be stripped from the body, with the whale rolled to retrieve the whole of the blubber. To assist this process the rope to which these strips were attached may have passed over shearlegs. The blubber would then be winched across logs or a granite surface and up to the tryworks for mincing and pitching into the trypots.

The nature of the flensing area is one of the major differences between the west and south coast stations in Western Australia. The majority of the south coast stations surveyed, particularly those with evidence of their tryworks remaining, suggest that the whales would be secured below a sloping granite shelf, sometimes (as with Cheyne Beach), in an adjacent scour channel. The granite would provide a smooth winching surface for dragging the blubber to the tryworks, in some cases up to 40 m away. Examination of the granite surfaces also suggests that some edges might have been removed or modified to reduce snags. Torbay was the only south coast station where such a stone ledge was not immediately evident. Similar use of granite sheets for flensing is also noted for South Australia (Kostoglou and McCarthy 1991:27).

The limestone geology and sandy shores of the west coast do not provide such natural advantages. It was in this environment that the jetties or timber ramps described in Dakin's (1934) or Little's (1969) descriptions would have been important if not necessary parts of the operation. The archaeological and historical evidence at the Bathers Beach presents the best picture of a working station, albeit the most elaborate operation in the colony. The jetty meant that the whale could be flensed in deeper water at the end or sides (Reece and Pascoe 1983:8), making it easier to roll and manipulate. The shearlegs and winch mounted on the end of the pier would aid this process. The blubber may have then been carried on trays or in carts across to the tryworks.

Direct evidence for jetties at other west coast sites is extremely limited. Early reports from the original Carnac Island station state that ‘considerable advance had been made on the construction of a jetty’ (PG 6/5/1837), but fail to mention whether this was to assist in processing. Bateman's Bunbury station of the 1860s has been variously described as being in the area of the jetty or breakwater (Mitchell 1927; Anon 1936), although it is difficult to determine if these existed during the whaling period. There are no historical or archaeological indicators for the other west coast stations. However, at Castle Rock and Port Gregory it would have been necessary to transport the heavy blubber up to 30 m over sand to the tryworks. It is possible that a simple ramp or surface of logs or planks would have allowed the blanket pieces to have been winched over the beach.

Malus Island, the northernmost whaling station, uniquely presents the difficulties of wide tidal variation. Whereas the southwest stations experience a tide range of no more than 1 m, the sea level around the Dampier Archipelago fluctuates by 3 m to 4 m or more daily during the winter months. It is possible that the whale carcasses were beached at high tide when they could be brought in close to the station, although whether or not flensing was easier at low tide with easy land access around the whale is unknown. As noted, flensing might have been carried out with the assistance of the schooner or 'cutting–in vessel', meaning that only the blubber had to be transported ashore.

An interesting piece of oral information collected at the Cheyne Beach site is that punts were used to assist in the flensing process (Charles Westerberg, pers. comm. 1989). Although there is no supporting textual evidence from Western Australia, Davidson (1988:126) shows a photograph of a small boat being used for just this purpose at the Kiah Inlet station in New South Wales. It is also possible that the ‘cutting–in’ vessels noted at some stations (see Chapter Three) were moored alongside the whale and used as platforms from which to flense, and if sufficiently large could have ropes passed over their masts or yards to assist in rolling the whale during the process (e.g. SAR 1/1/1842).

Carcass Disposal

During the 19th century the only body parts of right and humpback whales considered usable were the blubber and other oil–rich portions such as the tongue, and the baleen or 'bone' of the mouth. It was suggested early in the history of the Western Australian industry that the waste portions of the whale could prove to be a valuable source of fertilizer (PG 17/6/1837), although there is no evidence for this use being pursued. There is a single report of a German settler in Albany proposing to purchase whale skeletons and crush them (Inq 15/11/1871), but no further mention is made of this. This left the bulk of the whale carcass to be disposed of in some way, and in the case of the Fremantle Whaling Company the removal of the waste formed an essential part of the lease agreement for use of the jetty (PG 17/6/1837).

In the absence of historical documentation about disposal, the most likely method would have been to tow the carcass back out into the bay and let it sink in deep water. Sharks, ever–present around the whaling stations, would quickly strip the meat away and, it would be hoped, prevent it from washing back into shore. The archaeological support for this is the large quantity of whale bone which continues to be washed up on the beaches adjacent to the sites, even 150 years later. An 1880s visit to Cheyne Beach described it as the ‘valley of bones’ (Albany Mail 18/12/1889). Retired commercial fishermen interviewed during the survey invariably described the floors of these bays as being ‘covered’ in whale skeletons and recalled that their nets frequently snagged on or pulled up bones.

63Processing Area and Tryworks

Once the blanket pieces had been winched up from the beach and into close proximity with the tryworks, further processing was required to reduce the blubber into a size and form suitable for the trypot. The blanket pieces would be sliced into horse pieces, which were thrown onto a wooden trestle or 'horse' and minced, but not cut right through, to produce the 'sliver pieces' (Pearson 1983) or 'bible leaves'. This latter process could be done manually, although a mechanical mincing machine, now in the collection of the Western Australian Museum, was recovered from the Malus Island site. This is the only archaeological evidence for this intermediate stage detected on a Western Australian site.

Archaeological evidence for tryworks was identified at three sites on the west coast and three sites on the south coast. Five of the tryworks (Malus Island, Castle Rock, Barker Bay, Cape Riche, and Barrier Anchorage) were situated immediately above the probable flensing area, at the junction between the beach or granite shelf and the vegetation line. Historical maps of the original topography of Bathers Beach show that the tryworks was constructed against the cliff edge close to the jetty, the closest approximation in terms of position. It is presumed that these positions were chosen not only because they were above the high tide mark, but also to provide a stable surface on which the structures could sit. Unfortunately, most of the tryworks are still very susceptible to damage or destruction through storm surges and erosion. For this reason, with the exception of clearing the portion of the Castle Rock tryworks previously excavated by MacIlroy (1987), it was decided not to excavate, clear vegetation or undertake other investigations which might endanger the stability of these structures. Unfortunately, this means that their internal design remains unexplored. The structure of the tryworks is similar to contemporary examples elsewhere in Australasia (e.g. Lawrence 2006:53; Prickett 2002).

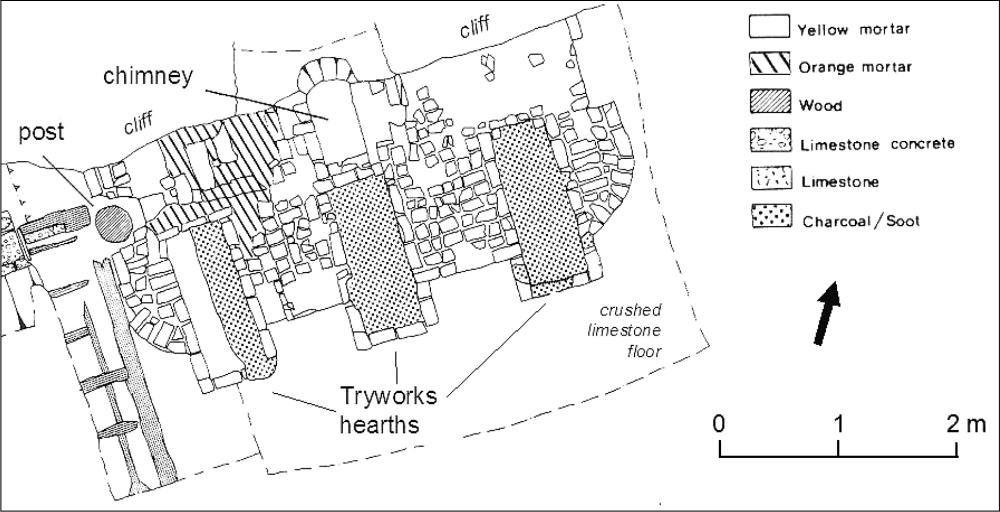

The historical and archaeological record suggests that two trypots were the norm in a Western Australian whaling station, although some stations apparently tried to make do with only one, sometimes resulting in the loss of oil (Inq 16/11/1864). In contrast, Bathers Beach is the largest surviving tryworks with excavations revealing a substantial three–hearth structure, indicative of the grand intentions at the time when the station was established(MacIlroy 1987; see Figure 4.14). With the exception of Malus Island, all of the trypots from the stations examined had been salvaged either historically or by 20th century collectors. From the remaining evidence it is obvious that as the trypots had originally been built into the tryworks structure (or more correctly the sides of the tryworks had been built around them), their removal required the demolition of the tryworks down to the foundation or base on which the trypots sat. However, the general dimensions of the surviving features allow a broad estimate of the original capacity of the tryworks (Figures 4.9–4.10).

Figure 4.9 Castle Rock tryworks.

Figure 4.10 Castle Rock tryworks.

Figure 4.11 Cape Riche tryworks.64

Figure 4.12 Barker Bay tryworks.

Figure 4.13 Malus Island tryworks (photo: E. Bradshaw).

The materials from which the tryworks were constructed vary slightly between sites. All of the surviving south coast tryworks only used the local granite, mostly mortared–together rubble, although some of the corners and edges might have been slightly dressed or squared. At Castle Rock and Malus Island the local granite was also used, but with brick quoins and edges. At Bathers Beach the whole of the structure is of brick, as was suggested for the Marmion station. It is not known whether granite provides better thermal qualities, or whether its use (rather than brick) was simply an economy measure which also obviated the need to transport heavy construction materials up. Brick was possibly used of necessity along the west coast as the local Tamala limestone reduces to powder under sustained heat. In the bases of the tryworks was a consolidated black organic substance presumed to have been the residue of the skin or 'scrap' which was fed into the hearths.

Descriptions and photographs from other areas of Australasia suggest that a tryworks shed, even if only a crude roof cover of some kind (Trotter and McCulloch 1989; Sinclair and Harrex 1978), was necessary, presumably to protect the oil from being spoiled by rain. Tryworks sheds are mentioned for Port Gregory (Inq 13/8/1837), Fremantle (Bavin & Gibbs 1988), Carnac (PG 22/4/1837), Bunbury (CSR 338/204) and Port Gregory (BL M386). The Bunbury ‘blubber house’ is described as being ‘30–40 feet [9–12 m] long, open on one side, and also shingled but only partly floored’ (Barnes 2001:62).

Figure 4.14 Bather Beach tryworks (Modified from MacIlroy 1986:47, original drawing by D. Meredith).

65In the case of the Port Gregory station run by Sanford and Harwood, the initial list of equipment needed to establish the station includes sheets of iron to roof the tryworks (BL M386; see Figure 3.2). Evidence that the rest of the Port Gregory tryworks shed was constructed of wood comes several years later, with a report that flame escaping from the hearth had ‘entirely consumed’ the building, including ‘a considerable quantity of fishing gear’ (PG 13/8/1858). Although there would have been precautions to prevent spillage of oil, it is almost inevitable that accidental losses over time would soak the timbers, making the structure susceptible to fire.

The only archaeological evidence for a tryworks shed is from the excavated Bathers Beach site, showing the tryworks situated within a building of considerable size (MacIlroy 1987). This building is depicted in Samson's 1840s sketch as an open–sided structure, with what appears to be a shingled roof supported by large wooden posts (Reece and Pascoe 1983). It is possible that the adjoining floor space could have been used to accommodate mincing horses, tubs and coolers.

No historical or archaeological evidence was found to describe the cooling tanks which sat immediately alongside the tryworks, ready to receive the oil as it was bailed out of the trypots (c.f. Lawrence 2006:56). One exception may be the stone lines adjacent to the Barrier Anchorage tryworks which were conceivably used as supports for a cooling tank, rather than the base of another hearth.

Oil Storage

To prevent shrinkage of the wooden barrel staves, which would result in the loss of oil, it was necessary to store the casks in conditions of stable temperature and humidity (Pearson 1983). Although it is possible that the Bathers Beach station used either their two storey station house or a cave in the cliff to store their oil (Bavin and Gibbs 1988), there is no archaeological or historical evidence at the other stations for the construction of a shed or shelter to protect their casks. It is possible that barrels were simply covered with canvas or seaweed or, as in one documented instance, buried in the sand until the time of retrieval (CSR 372/40: 21/8/1857).

Nash (2003:71) describes Tasmanian shore stations having a wood and/or clay lined storage pit (a ‘blubber hole’) for keeping any flensed blubber that could not be tried out immediately, such as due to a shortage of barrels. There is no historical or archaeological evidence for these structures in the Western Australian records, although their use seems likely.

Boat ramps & launching areas

All of the whaling station locations have a gently sloping sandy beach nearby which would allow whaleboats to be drawn up and if necessary out of the water. Positioned behind the headland, these beaches are also sheltered from most of the swell and surf of the open sea, although it is obvious at some of the sites that they are susceptible to heavy storm surges. It was also there, just below the station house, that the boats would rest in full readiness to be pushed out when the call came from the look–out.

There is no direct archaeological or historical evidence for rails or slips to let boats in or out of the water, although it is probable such structures existed at many stations. As described previously, the 1840s drawing of the jetty at Bathers Beach appears to show davits which could draw the boats vertically out of the water. This sketch, probably drawn during the off–season, also shows one whaleboat stored in the tryworks shed and another in the storage cave nearby. There is, however, considerable evidence to show that out of season the owners of whaling stations deployed their whaleboats for other purposes (Chapter Three).

Whalecraft storage and work areas

Shore whaling required a large body of specialised equipment for both the catch and processing phases of the operation (see Chapter Three), including sufficient replacements of irons, lances, shafts and whalelines which would be expected to be lost or broken during the normal course of the season. These items, including other necessities for both industrial and domestic functioning, would require a shelter or storage room to protect them from the inclement winter weather. A description of the Carnac Island station includes a building used as ‘residence and storehouse’ (PG 6/5/1837), suggesting that some portion of the barracks, possible even a second room or a lean–to, was used for this purpose. As an additional structure would involve increased cost and effort, it seems consistent with the limited scale of the stations to have such an arrangement. If an independent storage room was constructed, presumably out of wood as for the barracks (see below), the lack of a chimney would drastically reduce archaeological visibility as a structure.

Both before and during the whaling season there were also routines of maintenance and repair, with at least one member of the boat crew doubling as carpenter/cooper. The cooper would be required to put together the shooks (bundles of staves) in anticipation of the catch, a task requiring some judgment lest the station be caught without sufficient storage and the oil be lost (Inq 3/11/1847). Whaleboats also required maintenance during the season, ranging from repainting to major repairs when struck or 'stove in' by a whale during the chase. Finally, there must have been a stream of other minor chores to replace equipment, repair the stations buildings, and so on. Although a covered workshop was not essential, coopering and the repair of metal items would require at least a fire, although this could presumably be built on the beach.

Barracks and Domestic Buildings

Aside from their industrial function, most whaling stations were also the home for between 12 and 20 men for four to five months during the middle of winter. In 66later years the two stations closest to towns (Bunbury and Fremantle) may have opted for allowing the men to stay in their own homes nearby, only meeting daily for work (Inq 30/5/1849). In all of the other stations the distance from settlement demanded that accommodation and food be provided for the workers. At Fremantle the 1837 station house and storeroom was a substantial two–storey building constructed out of stone, and was consequently one of the main objects of expenditure by the company. However, for many stations it appears that the barracks and other buildings were at least partially pre–fabricated wooden or possibly canvas structures.

This use of wooden buildings is suggested by the archaeological remains found on the south and west coasts. Stone or brick bases of domestic chimneys were located at Malus Island, Castle Rock, Barker Bay, Two People Bay, Cheyne Beach, and possibly Torbay. A quantity of brick rubble, probably originating from a chimney, was also found at Port Gregory, while oral evidence suggested a stone domestic chimney was also located at Thomas Fishery. In all of these instances only sufficient rubble was found to reconstruct the lower portions of a chimney. There were insufficient extra material and no structural evidence to suggest stone or brick walls, with the possible exception of Cheyne Beach, as will be shown below.

It is possible that timber and bark was collected for slab huts at the start of each season, although the areas north of Fremantle and east of Cape Riche have little timber close to the stations which is suitable for structural purposes. A prefabricated wooden frame and stock of weatherboards, or heavy canvas sheets, could be transported by ship and re–erected on a site in several days or even less, eliminating the need for time–consuming collection and preparation of local materials. A timber building could also be removed at the end of the season and re–used elsewhere, rather than be left for resumption by the government at the end of the lease, destroyed by bushfires, or damaged by transient users. There are several references to wooden structures being sold to or from whaling stations (PG 22/4/1837; CSR 24/118: 4/12/1847). The Bunbury ‘dwelling house’ was a weatherboard building, ‘25 feet by 15 feet [7.5 x 4.5 m], shingle battened and floored (CSR 645/112: 28/6/1870; Barnes 2001:62). In 1871 John Bateman applied for permission to erect a two–roomed ‘portable house’ at Castle Rock for the use of his whaling crew (MacIlroy 1987: 22).

Use of timber structures did not necessarily mean transience, as locations such as Cheyne Beach, Barker Bay and even Castle Rock were occupied consistently by the same parties for long periods. In the case of Cheyne Beach the station was operated by John Thomas for at least 22 years and for at least some time may have been his family's permanent home. At the other end of the scale there is no information on living conditions during the late period of whaling, when the south coast parties moved between two or more stations per season. Whether they had buildings constructed at several sites, moved a wooden structure with them, or reverted to tents, is unknown. Even with a canvas hut it is possible that a stone or brick chimney for the hearth might be constructed.

The position of the station house/barracks falls into a recognizable pattern, usually situated on or just behind the foredune, directly above the beach. This was presumably to afford rapid access to the boats once a sighting was made. In the case of sites located adjacent to settlements (Port Gregory, Fremantle, Bunbury), the locations were circumscribed to varying degrees by the need to fit into the formal town subdivisions. Port Gregory exhibited the most anomalous station house location, with the site presumed to be the barracks situated some distance behind a substantial set of sand dunes which make access to the beach an arduous task (see also Rodriguez et al. 2006). However, in this instance the whalers were housed in a storehouse constructed by Captain Sanford within the subdivision of the proposed Packington town, rather than in an especially built beachside barracks.

The locations of the habitation sites is usually upwind of the flensing and tryworks areas. To a degree this is a function of the morphology of the bays, and the swell and wind conditions which create them. However, in many cases the site chosen for the barracks is about 100 m from the processing area, still in close proximity, but sufficiently removed to avoid the worst of the smell.

Other Structures

As noted earlier, in the interests of economy and expediency, as well as the nature of the lease of land, the number of buildings at each station was probably minimized. However, there remains the possibility of other structures beyond those mentioned above. To use Cheyne Beach as an example again, there is archaeological and structural evidence to show that there were multiple buildings in the habitation area of the site. In an anecdotal account of the station there is an incidental mention of a ‘cookhouse’, presumably a kitchen separate from the barracks (McKail 1927). This may correspond to the small hut located east of the main building excavated at the site. There was almost certainly a house for John Thomas and his family, also probably in fairly close proximity to the other station buildings.

Water Supply

It is presumed that all of the stations would have had wells or otherwise attempted to secure stable supplies of fresh water, although historical evidence is limited (e.g. Albany Mail 18/12/1889). While the southwest of Western Australia can be dry during summer, the fact that the shore whaling industry was carried on in winter meant that there would have been less concern about water. When the various sites were surveyed between July and November all had readily visible water supplies through seasonally active streams and large volume runoff from adjacent hills and headlands. Water is less certain to the north of the Swan River, although at Port Gregory fresh 67water could be collected from the nearby Hutt River pools, or by digging wells in the inter–dune areas near the station. It is not known if there is fresh water on Malus Island.

No physical evidence of wells directly associated with any of the whaling stations was located, although lined wells of some antiquity have been reported in the general vicinities of Doubtful Island Bay and Middle Island, neither of which could be visited during the survey.

Gardens

Although the question of food supplies is dealt with in the following chapter, clearance and preparation of ground for vegetable gardens to supply the needs of the station should be considered. In several instances foreign whalers were reported as planting gardens on both the mainland and offshore islands (PG 30/1/1841; Eyre 1845; Gibbs 2000). However, the only direct reference to gardening by a colonial party is the 1880s description of Cheyne Beach (Albany Mail 18/12/1889) and oral evidence which suggested the low lying swampy area behind the site had been used for this purpose (C. Westerberg, pers. comm. 1989).

Burials

Despite there having been a number of fatalities in the whaling industry (see Chapter Three), the only instance where the bodies seem to have been buried at a station is the two graves reputed to be at Doubtful Island Bay. Unfortunately it was not possible to visit the site during the survey.

Aboriginal Sites

The historical evidence for Aboriginal groups frequenting whaling stations during winter has been discussed in Chapter Two. If we assume that large groups did seasonally congregate at or near the stations for several months, it is probable that Aboriginal sites containing a high proportion of glass and other European materials should exist within several hundred meters of the whaling station sites.

Given the constraints on the survey and the low surface visibility in the coastal zone around the whaling stations, it was not possible to extend the investigation to locating Aboriginal sites. The potential of such sites as a valuable source of information on the archaeology of the contact period is recognised, as is the greater probability of their survival in those places still at some distance from intensive urban development.

DISCUSSION

The historical and archaeological evidence demonstrates that despite environmental differences there were common characteristics in the majority of the whaling station sites which suggest what were considered desirable features in terms of location and organisation. The following list summarizes these features and the results of the survey.

a. Shore whaling activity was based in bays or other semi–sheltered areas, while the station itself would be situated in a protected area, frequently adjacent to a headland or high dune.

b. A look–out would be based on the headland or dune, within view of the station. A nearby island might be used if this location increased the view or range of the spotter. On the south coast a low windbreak or shelter might be constructed to protect against the worst of the wind and rain.

c. On the south coast the whales would be fastened and flensed in a channel below a granite sheet. The blubber would be winched across the granite to the tryworks, which was sited along the edge of the vegetation line (presumably above the level of most storm surges). On some west coast sites the whales were brought in next to jetties for flensing, while at others they must have simply been brought into the shallows and the blubber either carried up to the tryworks or possibly winched across logs or planks. West coast tryworks were also situated on or just above the vegetation line.

d. Although a triple tryworks was constructed at Bathers Beach, most stations appear to have used only one or two trypots. The construction materials varied depending upon the friability of the local stone and access to bricks. The design of the tryworks appears to have been similar, with the opening to the hearth at the front of the base, and a flue or chimney at the back, although internal design could not be investigated. With the exception of Bathers Beach, evidence for covering shelters or sheds was limited to historical references.

e. All of the sites had a sandy beach, presumably on which to pull up the boats.

f. The domestic areas were constructed above the sandy beach, usually on or behind the first dune. In most instances the visible structural evidence was limited to a single chimney or a scatter of bricks or stone suggesting such a structure. It is probable that a wooden prefabricated barracks were used at most stations.

g. There was only limited historical and archaeological evidence for other buildings such as storerooms or oil stores, cooperages or boat sheds.

h. Potential sources of fresh water (at least during winter) could be identified near each site.

In considering the various characteristics of the whaling station sites, it appears that the most significant feature influencing selection was the sheltered harbour. This was also the feature most noticeably lacking from those places used for only short periods, including Sorrento, North Fremantle, Minninup and Toby Inlet. As noted previously these locations were occupied only after the more desirable positions in each area had been claimed. However, even these locations exhibit some of the features of the other sites, such as slight curves in the line of the coast, adjacent high dunes, or visible water 68sources nearby. It is probable that another shared characteristic was that whales were known to pass near these points on the coast.

Despite the historical evidence that some stations had different periods of occupation, while others had whole or partial re–buildings of tryworks and station houses over time, there was little surface archaeological evidence found at the sites indicating different phases of use. The one exception is Malus Island, where the two sets of tryworks might be interpreted as the remains of Pearse and Marmion's 1870–72 station, as well as Bateman's 1877 plant. The simplest explanation for the lack of archaeological evidence for successive occupations is that structures were re–built or materials re–used as necessary.

The general impression gained from the surveys is that over time the whaling stations on both coasts became simpler, with minimal permanent infrastructure. On the west coast the stations opened with elaborate buildings, jetties and other site improvements, while later sites have no historical or archaeological evidence for these major developments. On the south coast the whaling establishments were always fairly simple, taking advantage of natural features where possible. However, the stations at Barker Bay and Cheyne Beach, which were occupied for considerable periods of time, do show evidence of quite well developed domestic areas, compared to the scant features of the later camps. The long–term use of Castle Rock by the same party also seems to have resulted in more substantial domestic arrangements.

The apparently decreasing sophistication of the whaling stations corresponds to what might be expected from the historical patterns outlined previously. The high hope for expansion which characterised the first phase of the industry is reflected in the capital intensive development of the stations. The failure during the first several seasons to achieve significant returns resulted in a simplification of the industry, while the short terms and nature of the lease agreements discouraged efforts towards making expensive fixed improvements. In the later phases of the industry the move towards mobility and the use of multiple stations for shorter periods would also have encouraged the establishment of only simple (and possibly easily transportable and removable) facilities.

Comparison to other Australasian whaling industries

Given the similarities of the industrial processes and requirements of the workforce, it is not surprising that the basic site location and organisation of the Western Australian shore station is comparable to other documented Australasian sites: a sheltered bay or inlet, tryworks constructed above the beach, and housing for the workers on the hill slopes or dunes above, often with a freshwater creek nearby (e.g. Kostoglou and McCarthy 1991; Lawrence and Staniforth 1998; Prickett 2002; Nash 2003; Lawrence 2006). Without a better documentary record or large–scale excavations on several sites (c.f. Lawrence 2006) it is difficult to make definite statements about the nature of the sites. However, it seems safe to conclude that the Western Australian stations come at the lower end of the scale in terms of size and apparent complexity. The substantial stone buildings found at many of the Tasmanian, New Zealand and even South Australian stations (Kostoglou and McCarthy 1991; Prickett 2002; Nash 2003; Lawrence 2006) do not have clear equivalents in the Western Australian sites. The majority of the Western Australian station quite probably come closer to the small cluster of timber and bark ‘whalers huts’ drawn at Wilson’s Promontory in Victoria in 1843 (Lennon 1998:65). The exception is the elaborate two–storey Bathers Beach barracks and storehouse, which bears some resemblance in form and scale to the ‘whaling barn’ at Mosman, New South Wales (Gojak 1998:12).

Whereas the Western Australian whaling parties frequently consisted of only 12 men and station sites have archaeological evidence for only one or maybe two domestic chimneys, some of the Tasmanian and New Zealand stations were veritable villages, with semi–permanent populations of 80 or more men and an unknown number of women and children (Morton 1982; Evans 1983; Prickett 1998:50). The nature of the New Zealand stations was also influenced by the close social and economic relationships with local Maori groups, including the whalers taking of Maori wives (Coutts 1976; Morton 1982; Prickett 2002). While these large stations were the upper end of the industry, figures of between 20 and 50 men still appear normal. In consequence, the domestic areas recorded during archaeological surveys of whaling station sites reveal evidence of multiple domestic buildings (Campbell 1992; Prickett 1983; 2002; Jacomb 1998; Kostoglou and McCarthy 1991; Bickford, Blair and Freeman 1988; Prickett 2002; Nash 2003; Lawrence 2006).