APPENDIX A

SITE HISTORIES AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEYS

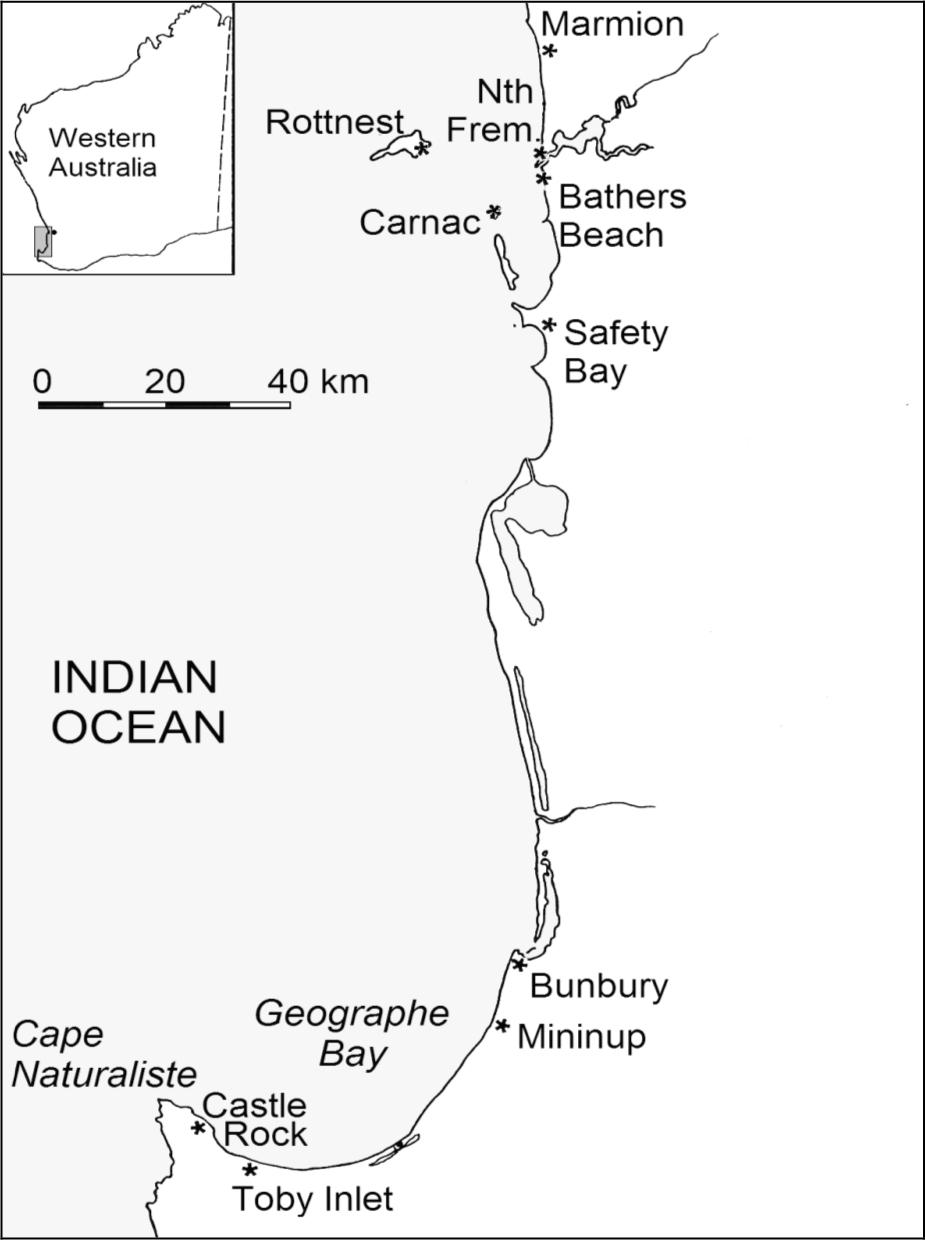

The following Appendix provides a brief history and archaeological description of shore whaling at 21 locations along the west and south coasts of Western Australia. A more detailed historical and archaeological description is available in Gibbs 1996. Analysis of the site histories and components is provided in Chapter 4.

SURVEY METHOD

As noted in Chapter One, several 19th century whaling station sites had been identified during the 1970s and 1980s. The National Trust (W.A.) survey of whaling stations in particular drew on Ian Heppingstone’s historical research to identify 20 probable locations for whaling activity, with MacIlroy’s survey identifying seven sites with structural remains or artefacts (MacIlroy 1987:1). These identifications provided a solid basis for the current study, commenced several years later.

Based on a more comprehensive historical analysis, several of the locations suggested in the 1987 study were eliminated as misinterpretations of the historical records (Ten Mile Well, Collie River and Augusta). A total of 21 locations, such as specific bays known to have been used the site of one or more shore stations, were identified. In addition, further clues were generated as to probable site locations in bays which had previously been surveyed unsuccessfully.

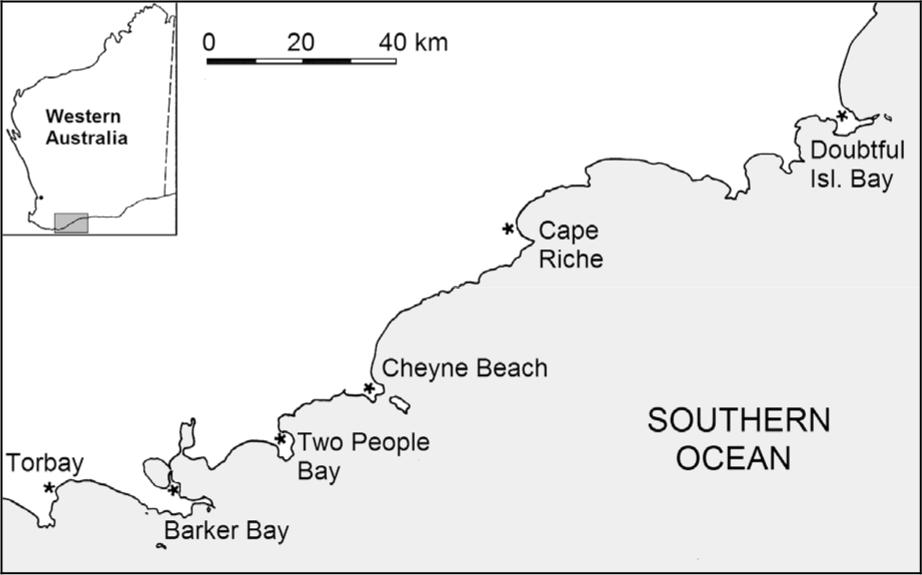

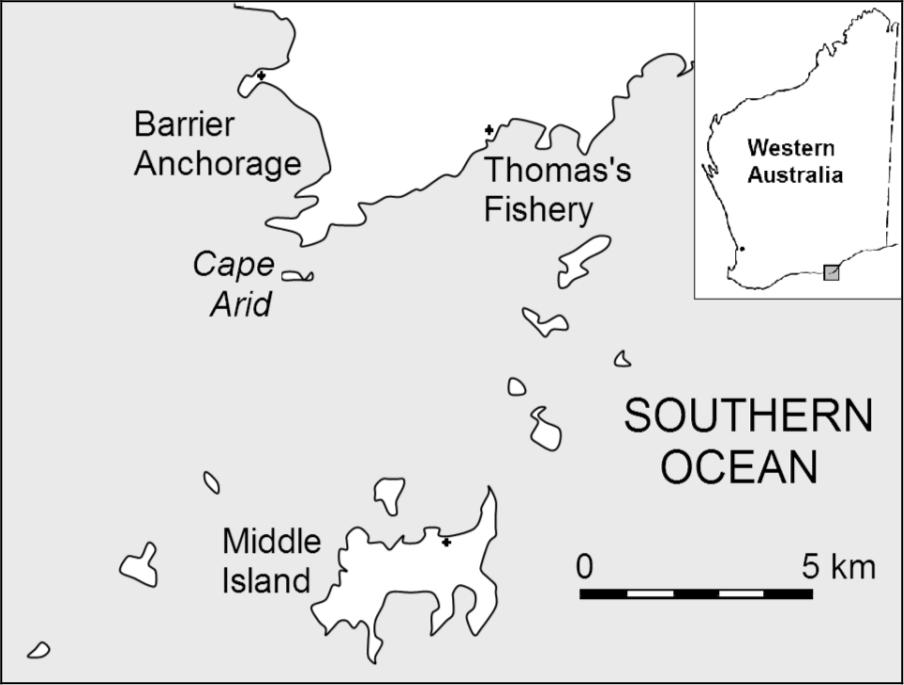

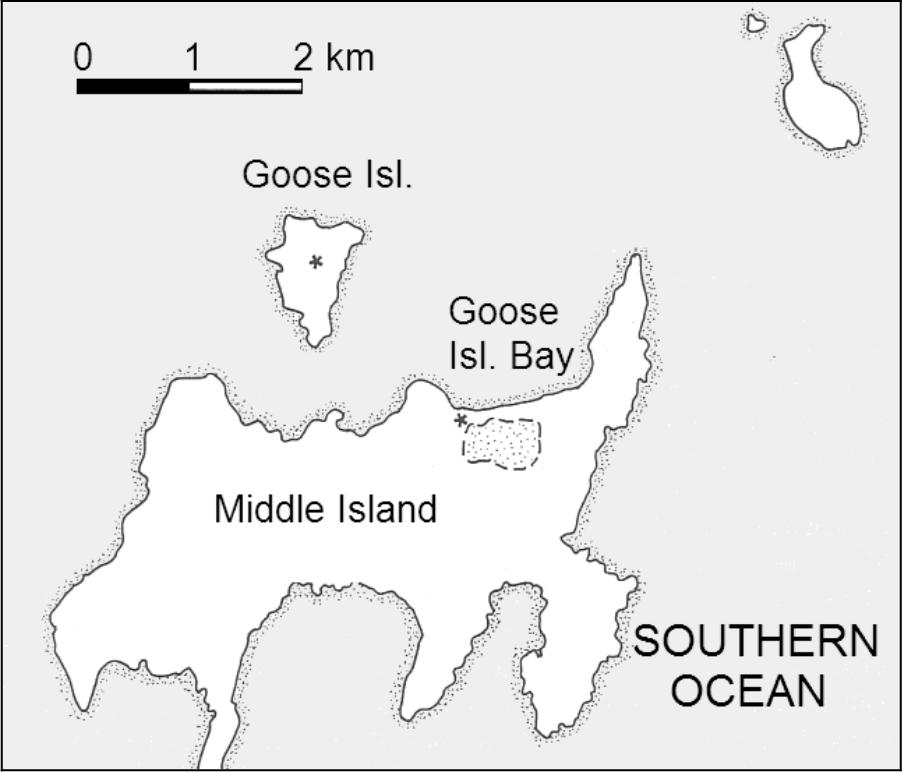

Surveys were undertaken in several stages between 1990 and 1993, with the very limited funding available meaning that the more distant or inaccessible locations could not be visited. Initially the most accessible sites on the west coast between Port Gregory and Castle Rock were surveyed, followed by the south coast sites between Torbay and Cape Riche. Finally, the remote sites of Barrier Anchorage and Thomas Fishery were surveyed. Four locations (Malus Island, Carnac Island, Middle Island and Doubtful Island Bay) could not be visited. For these places it was necessary to speak to local informants and use other sources of information to assess the existence or condition of the sites.

NORTHWEST COAST

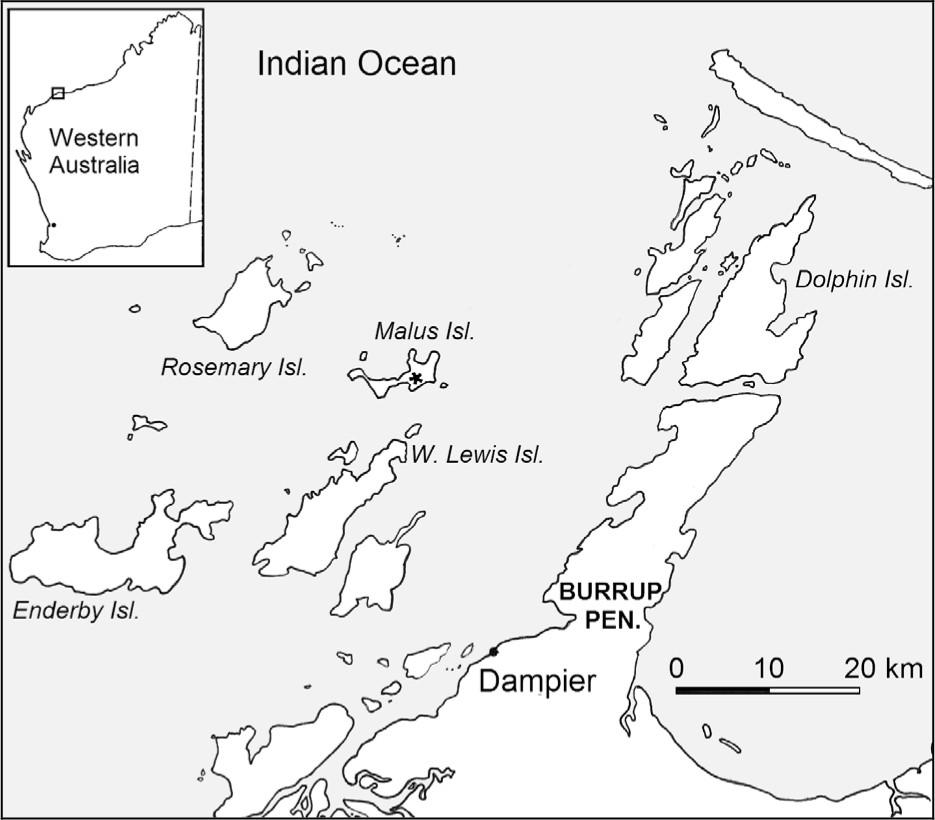

Malus Island is part of the Dampier Archipelago, a collection of islands up to 15 km long and 3 km wide which are clustered along the west and north sides of the Burrup Peninsula. The archipelago is a drowned landmass ‘characterised by rock platforms and storm boulder beaches interspersed with localised accumulations of sand and silt in the more protected embayments’ (Vinnicombe 1987:2). The area experiences large tidal variations and has relatively warm and dry winters (Woods 1980). Winds are easterly during winter, although there is a west to northwest sea breeze. The swell is weak, arriving from the west, although the tidal variation is large. Winters within this region are relatively warm and dry, with cyclones through the summer (Woods 1980).

Figure A1 Dampier Archipelago.

MALUS ISLAND

Date Range: 1870 –1877

Location: Whalers Bay, SW section of Malus Island.

1:100,000 AMG Reference: 2256 Dampier 672–311

History

Although intensively used by foreign whalers since at least the 1840s, colonial whaling in the Dampier Archipelago ('Rosemary Islands') only dates to the 1870s and the establishment of pastoral and pearling outposts in the area (Wace and Lovett 1973:13). Initial use coincides with the establishment of pastoral and pearling outposts in the Roebourne area. In 1870 W.S. Marmion and W.S. and G. Pearse, established a shore station on Malus Island, using the 34 ton schooner Argo to assist operations (Inq 20/7/1870). In 1872 John Bateman also sent a party northward in 1872, forming a partnership with the Roebourne merchant George Howlett and using his 104 ton schooner Mary–Ann (Inq 9/10/1872). It is uncertain where Bateman's shore base was located, although reports mention the Mary–Ann working around Rosemary Island (Inq 12/6/1872). It is interesting to note that the masters of the vessels were also required to sign articles with the rest of the men 122(GG 4/6/1872; GG 25/6/1872).

After a poor 1872 season (Inq 9/10/1872) there was a hiatus until 1877, when Bateman leased Malus Island for the sum of £1 (SDUR B10/1144C: 12/1/1877). His son Francis managed the party and also acted as the master of the 70 ton schooner Star (PG 26/6/1877). This was the last recorded use of the station. The Blue Book records of oil taken at Malus Island during 1870–72 are unclear and it appears that at least some was recorded as 'Fremantle'. The 1877 catch by the Star was reported as amounting to 147 casks, probably totalling between 2.5 and 3.5 tuns of oil (PG 23/11/1877), but was not recorded in the Blue Book at all.

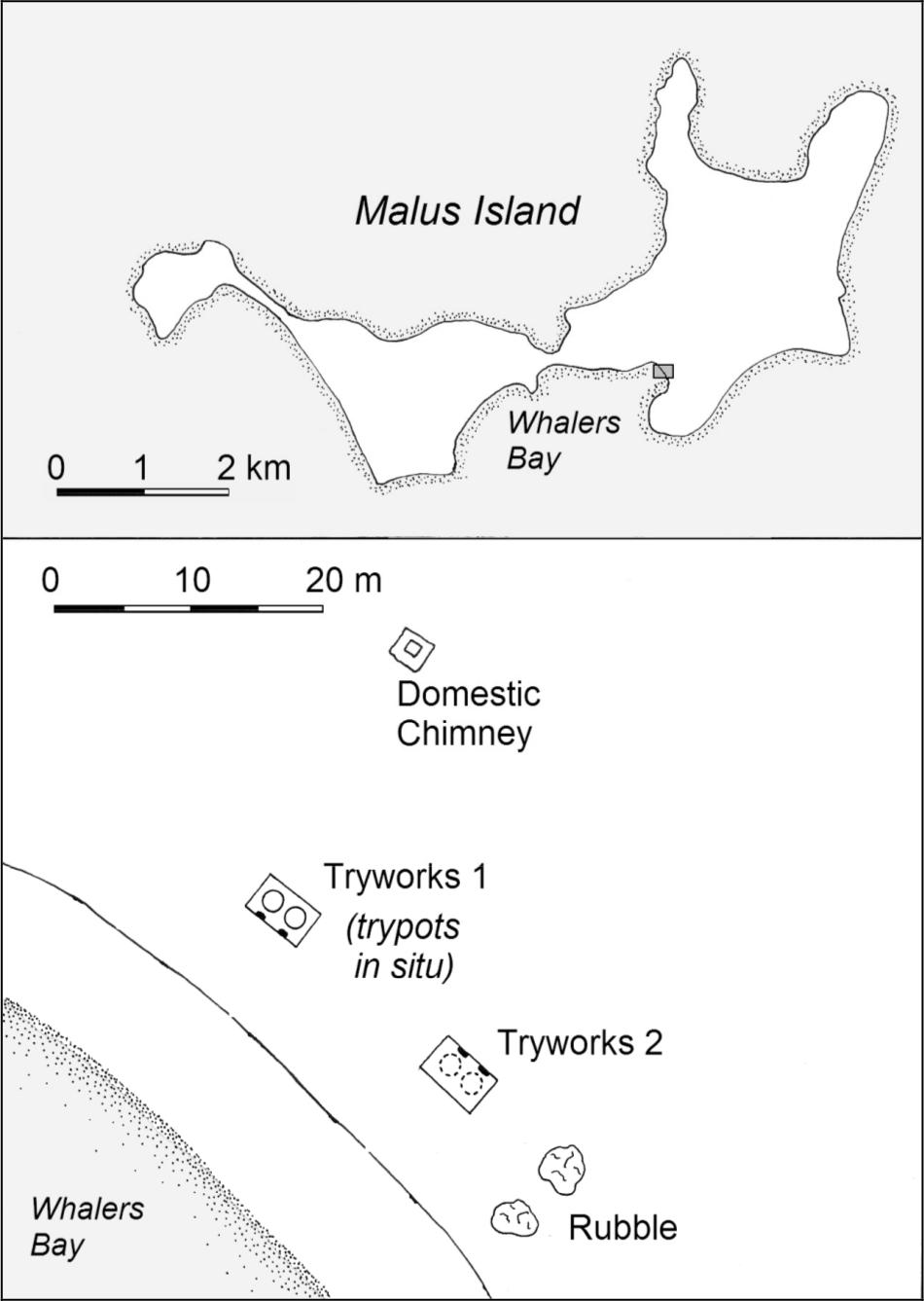

Figure A2 Whalers Bay, Malus Island.

Site Description

The site of the Malus Island whaling station was partially recorded by Western Australian Museum staff during the 1960s and 70s, and was re–inspected during the 1987 National Trust survey (MacIlroy 1979; 1987). While it was not possible to visit Malus Island during this current study, further photographs of the tryworks and samples of the char deposits in their hearths were collected by a colleague undertaking a survey for prehistoric sites (E. Bradshaw pers. comm. 1993).

The whaling station is located in Whalers Bay, a sandy cove on the sheltered SW side of Malus Island. The archaeological features include two double tryworks and a possible domestic fireplace. Until the late 1960s all four trypots were in situ, the only site in Western Australia where this occurred (Figure 4.13). Two trypots have since been removed, destroying one tryworks, while an amateur reconstruction has partially compromised the integrity of the other. The close proximity of the two tryworks may represent two separate phases of use of the site.

Figure A3 Whalers Bay, Malus Island.

MacIlroy (1987) also located a small stone structure, possibly the base of a domestic hearth or oven, approximately 20m northeast of the tryworks. The position, slightly inland and upwind (prevailing winds are westerly) of the tryworks is consistent with the spatial relationships seen at other sites. In the 1980 reconstruction of the tryworks the chimney was also rebuilt as the mounting for a commemorative plaque (E. Bradshaw, pers. comm. 1993).

LOWER WEST COAST SITE SURVEY

The lower west coast stretches from approximately Kalbarri to Cape Naturaliste and is characterised by long, straight sandy beaches with few significant bays or interruptions (Woods 1980). Old limestone dunes have become islands and headlands in some areas, with southwest swells and waves creating crescent–shaped northward opening bays behind these hard points. This varies slightly in the area close to Cape Naturaliste, where the granite of the Leeuwin–Naturaliste Ridge outcrops on the coast, with several small, sandy bays forming in between. The Castle Rock station is situated in one such bay. A strong south to southwesterly sea breeze is experienced along the lower southwest coast, although there are occasional strong northwest storms. Tidal range is very small and for the most part the areas behind the headlands are well protected. The region experiences a Dry Mediterranean climate with mild, wet winters.

123PORT GREGORY

Date Range: 1854–1875

Location: North end of Port Gregory harbour, behind Eagles Nest Hill.

1:100,000 AMG Reference: 1741 Hutt 289–790

History

A whaling station was established at Port Gregory several years after the opening of the area to European settlement, following reports of sperm whales ‘literally swarming’ on the coast adjacent to the harbour (Inq 26/1/1854). Captain Sanford, owner of nearby Lynton Station, formed a whaling party in partnership with Fremantle businessman David Ronayne (Inq 3/5/1854). Although the whaleboats were lost as they were being shipped northwards (Inq 12/7/1854), replacements were found in time to proceed with the season. However, only one humpback was caught (BB 1854).

Sanford operated his station again in 1855, hoping to attract one of the major whaling parties up to the port (BL M386; Inq 22/8/1855). In 1856 he was partnered by Joshua Harwood of Fremantle to run a three boat, 22 man fishery (GG 10/6/1856). Harwood maintained a party at Port Gregory until 1860, after which he ceased all of his whaling operations. In 1857 John Bateman also established a station at the port, which he continued to use intermittently until as late as 1875. From the early 1860s Bateman kept his party at Port Gregory from June to September, after which he would move them southward to Bunbury or Castle Rock.

Harwood's crew is known to have lived in Sanford's storehouse, built on Lot No. 1 of the proposed Packington town (BL M386). Bateman would probably have also been required to lease land within the Packington town subdivisions, although no record of this has been found. There are no historical references which pinpoint the location of either Harwood's or Bateman's processing areas or tryworks, although several contemporary sources indicate that the station(s) were opposite Gold Digger Passage (e.g. Inq 29/6/1859). The only other reference directly relating to a processing plant is a report from 1858, which states that the tryworks building and a considerable quantity of whaling gear had been completely destroyed after catching fire from the tryworks furnace (PG 13/8/1858, Inq 18/8/1858). As Bateman had not formed a Port Gregory station that season this could only have been Harwood's plant. An 1883 plan of the area shows what might be a structure on the beach in front of Lot No. 1, although as this was 30 years after the whaling period the association is questionable (Rodrigues 2006: 3).

Site Description

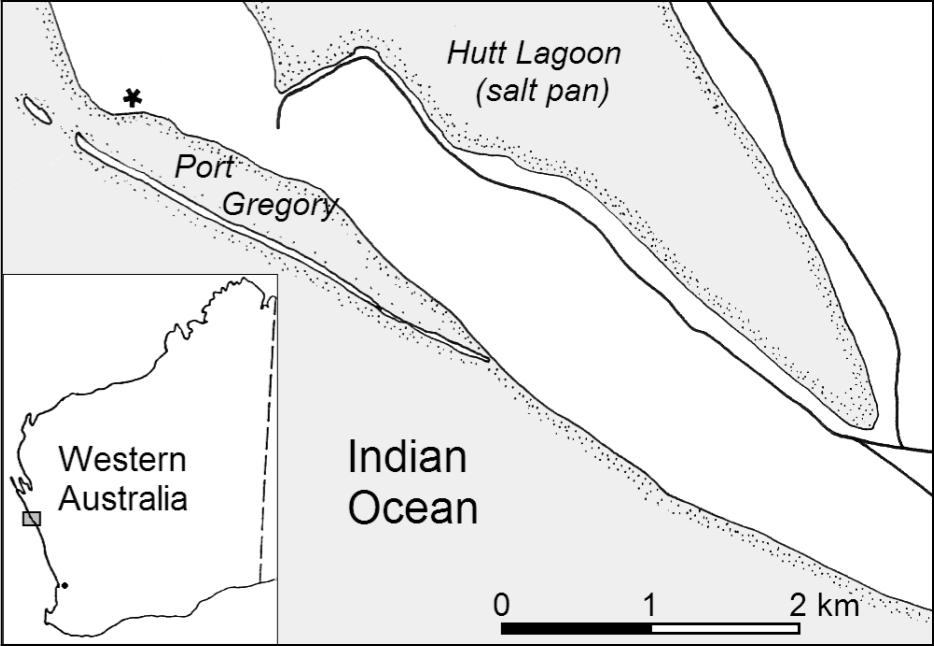

Port Gregory is a lagoon formed by a reef running parallel to the coast for 3 km. The enclosed area of water forms a safe harbour for boats and small ships and is entered through one of three passages on the far northern end of the reef. High dunes surround the bay from juts above the high tide mark, with lower dunes behind. An early chart also notes that good water is available two feet below the surface (Roe 1854).

Figure A3 Port Gregory Location.

Figure A4 Port Gregory Site Plan.

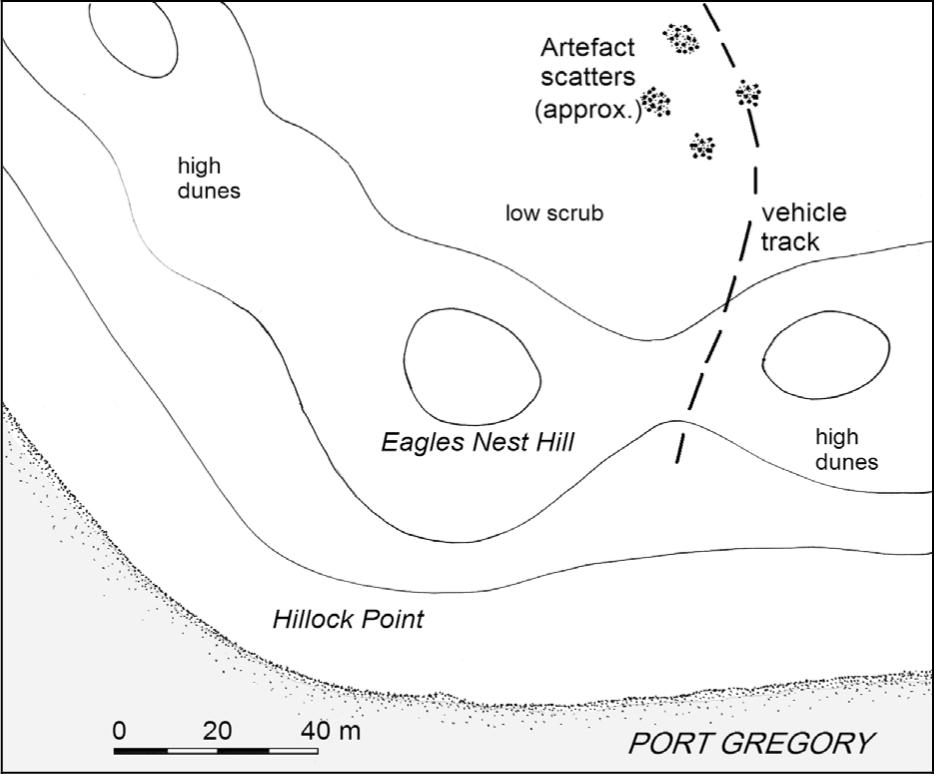

As early as the 1950s, historical studies had associated the scatters of bricks and artefacts found behind the Hillock Point dunes with early whaling activity (Suckling n.d.; Kelly 1958). In 1986 the W.A. Maritime Museum relocated the site and collected surface artefacts (M. McCarthy pers. comm. 1990). Several features were recorded by the 1987 National Trust survey (MacIlroy 1987) and the site was visited again in 1990 as part of this study. A further inspection was made by the W.A. Museum in January 2006 to investigate reported disturbances and newly visible features eroding out of the dunes.

Possible archaeological evidence of the station is visible in two areas. Behind the dunes approx 250m ENE of Hillock Point are several scatters of early brick and squared limestone which may have come from hearths or chimneys, although the source of these is 124uncertain. This area also contains light surface scatters of 19th century bottle glass, shell, ceramics, ironwork and bone, exposed in some areas by vehicle tracks and dune deflation. A 1m2 test pit indicates that artefact deposits exist to a depth of 50cm. It is difficult to determine positions relative to the original land divisions, although this material is likely to fall within or close to the position of Sanford’s Lot No. 1. The 2006 survey identified what appears to be a pug floor surface eroding from a vehicle track cutting through the dunes (Rodriguez 2006: 17-20).

Figure A5 Port Gregory looking north towards point.

The second site consists of material eroding from the beach–side dune face. This includes further brick rubble and iron both on the beach and in the dune face, The 2006 survey also identified chunks of black organic matter which may be pyrolised animal fats such as from a tryworks, although these have not been analysed further. No evidence of a look–out was found, although the high sand dunes on Hillock point would provide good elevation.

MARMION/SORRENTO

Date Range: 1849

Location Approx. 25 km north of Fremantle.

1:100,000 AMG Ref: 2034 Perth 813–714 (approx.)

History

After unsuccessfully bidding for the 1849 lease of the Bathers Beach station, Patrick Marmion requested the lease of an area 20 miles north of Fremantle. The position was described as

Eastward of a little Island which is about 2 miles from the main. The spot in question is also a mile, or perhaps two miles northward of the parallel of the northwest of Rottnest Island. It is also…about 3 miles west or west by south of Wanneroo (CSR 4/7/1849 cited in Daniel & Cockman 1979: 6).

Marmion was granted permission to occupy the 10 acres rent free, with liberty to run sheep on the adjacent Crown land for the purposes of the station (Daniel & Cockman 1979: 6). Marmion regained his lease of Bathers Beach in the following 1850 and there is no further evidence that the Marmion station was ever used again. Physical evidence did, however, survive for some time. In his application to the Governor, Marmion stated his intention ‘to erect a house for the whalers, to set a proper sort of tryworks with English bricks etc, and make this affair not a merely temporary concern’ (CSR 4/7/1849, cited in Daniel & Cockman 1979: 6). While no further description is available, a small allotment with a feature marked as ‘Marmion's Chimney’ appears on various maps of the area through the rest of the 19th century which might indicate the tryworks or more likely the whalers’ barracks (Daniel & Cockman 1979).

Figure A6 Lower West Coast Sites.

Site Description

There are few environmental features which would recommend the location for a station. There is a slight projection in the coast several kilometres northwards at Mullaloo Point, although this provides none of the advantages of a headland as a protection or look–out. The only particularly desirable feature was the presence of freshwater springs, noted on early plans (Daniel & Cockman 1979). Recent changes to the coastline and 125urban development makes it difficult to assess other contributing attributes. There is no remaining surface evidence for the station and its precise location cannot be determined, although a memorial plaque has been erected near the beach by the Royal Western Australian Historical Society.

NORTH FREMANTLE

Date Range; 1856

Location: Unknown, north side of Rous Head?

1:100,000 AMG Reference: 2034 Perth

History

Evidence for the existence of a shore–station at North Fremantle is limited to several minor references. The first is by Butchart (1933) in his childhood recollections of whaling activity about Fremantle, who simply states that ‘Bateman had his plant on the south side of the river, and Harwood on the north’. Similarly, Hope (1929) recalls as a child in 1865 ‘when whales were caught in the harbour, there was a boiling down establishment at North Fremantle, near the present wheat sheds’. He notes that he last saw the remains of the station in 1875. It is possible that Crammond's (1935:5) description that ‘in 1855 there was also a plant at North Fremantle, situated near the river where large boilers and vats were used for boiling down’ is based these earlier comments.

No direct historical documentation has been found to support the existence of a North Fremantle whaling station, while Harwood's station would appear to have been located on Carnac Island (see above). However, during the 1856 season a third whaling party (other than Bateman's or Harwood's) was reported as operating in the Fremantle region. With the two most suitable locations already taken, North Fremantle may have been the nearest available position where a shore station might be established. The unidentified third party did not survive its first season before dissolving (Inq 24/9/1856).

Site Description

In the early period ‘North Fremantle’ included a large area on the north side of the Swan River, almost to Rocky Bay (c.f. le Page 1986:126). The area around the mouth of the Swan River has been massively altered by harbour development and it is unclear from early maps whether a small cove or sheltered area existed that might have been suitable for a station. Hope’s (1929) recollection that men from the station sometimes quietly left the St John’s (Fremantle) Church service when a whale was sighted would suggest that it was nearby, as does his reference to the wheat sheds, many of which were on the north side of the harbour at this time (Shaw 1979:336). There were various high hills and dunes which could have been used as a look–out, while Butchart (1933) mentions a 'Whaler's Hill' at Cottesloe.

As with the Marmion fishery, the North Fremantle station appears to have been based on the more desirable locations already being occupied. Except for its proximity to Fremantle, the area has little to offer for a whaling station, being directly exposed to winds and swell. The short period of operation and subsequent heavy landscape alteration makes the survival of archaeological remains highly unlikely.

BATHERS BAY / FREMANTLE

Date Range: 1837–c.1861 (-1875?)

Location: Bathers Beach below Arthur Head.

1:100,000 AMG Reference: 2033 Fremantle 809–524

History

The small bay immediately south of the mouth of the Swan River, later known as Bathers Bay (or Bathers Beach), was a focus for early settlement activities at Fremantle. All settlers and supplies were landed on this beach until the construction of deep–water jetties at the adjacent point and the eventual removal of a river bar in the 1890s. The other side of the headland was also where the first European colonists camped and is now the City of Fremantle,

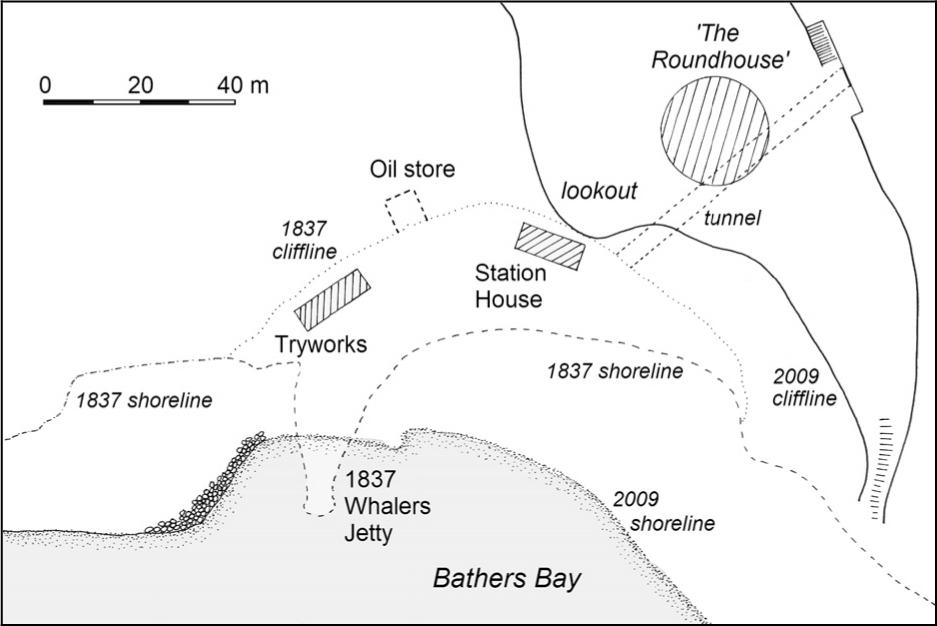

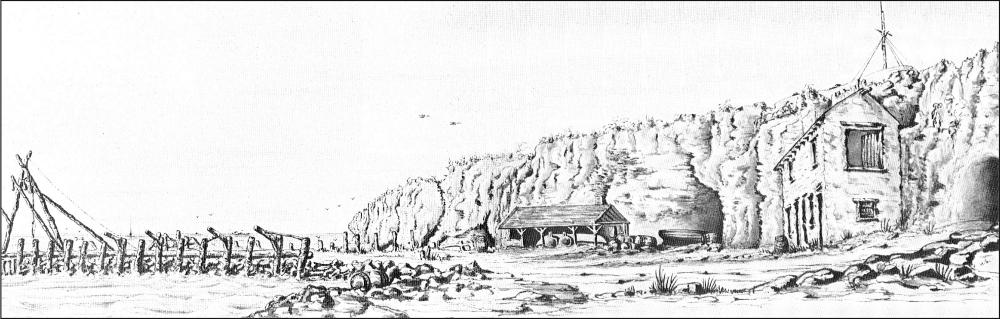

In 1837 the Fremantle Whaling Company obtained a five year (in some reports seven year) lease on Bathers Beach, constructing what would prove to be the most elaborate whaling station in the colony. Improvements included a two story stone station house, a wooden tryworks and boat shed, storage rooms cut into the base of the headland, a stone jetty and a tunnel through the headland to the town beyond. The last two works were granted government assistance in the form of engineering expertise and convict labour, as the jetty would also become the main landing for the colony and the tunnel a means of easing access between the port and the town.

The 1837 and 1838 seasons were very poor (See Chapter 2) and from at least 1839 the company appears to have chosen to lease the premises to private operators, rather than attempt to form a party of their own. During the early 1840s the station was most frequently rented to Captain Daniel Scott, although other identities such as Patrick Marmion and Capt. Anthony Curtis are also known to have taken the lease for one or more seasons. The Fremantle Whaling Company was finally dissolved in 1850 and its equipment auctioned (Inq 4/12/1850).

An 1840s drawing of the station (Reece and Pascoe 1985: 8) provides an accurate representation of the station, showing the station house, tryworks shed, jetty and a cave–like opening in the cliff corresponding to what is shown in historical plans as the oil store. The jetty is stone between wooden pilings, with shearlegs at 126the far end, likely used to assist in stripping the blanket sheets from the whale. This suggests that whales were beached or secured at the end or sides of the jetty, rather than brought right in to shore. The horizontal beams projecting from the right hand piles of the jetty appear to be davits for pulling one or two boats out of the water, similar to those used at the Boyd station jetty in New South Wales (Davidson 1988:79). On the headland above is the platform and signal mast from which the look–out was kept (PG 6/5/1837).

Figure A7 Bathers Beach Site Plan.

From the 1850s onwards John Bateman, merchant and former headsman for several Fremantle parties, became the regular lessee of the Bathers Beach station. However, this may have only included the jetty and processing buildings, as the station house had already been leased to the Convict Department (CSR 222/190: 7/7/1851). This raises the possibility that Bateman’s crews were housed in his nearby warehouse or in their own homes. During the 1850s the catch from the Fremantle area fell to no more than 25 tuns of oil (Bathers Beach and Carnac Island) combined.

Increased traffic through the port and the growing town behind may have encouraged the abandonment of the station, with its last confirmed use by Bateman being in 1861 (Inq 21/8/1861). Despite this, in 1863, 1865, and 1867–1875 a 'Fremantle' entry is recorded in the Blue Books and reported as including between two and eight boats. This suggests that there were one and sometimes two parties in operation in the area, leaving open whether there were also stations at North Fremantle, or that it refers to a station on Carnac Island (see below). In several years the total catch for the area was around 40 tuns of oil, a considerable quantity for that period.

No contemporary sources confirm a continuing use of the Bathers Beach station. However, in 1865 a report of whales near Fremantle laments the absence of whaling equipment ‘in the absence of Mr. Bateman's plant, which is now stationed near Bunbury’ (Inq 18/10/1865). This leaves some ambiguity as to whether Bateman had moved to a southern station permanently, or had used Bather Beach in the first part of the season and shifted to Bunbury for the late part of the season.

The jetty and buildings may have remained in use for some time into the late 19th century, when progressive quarrying and landfill eventually covered the structures (Bavin and Gibbs 1988).

Site Description

MacIlroy’s excavations at the site of the Bathers Beach whaling station have revealed substantial structural remains from the early whaling period (MacIlroy and Meredith 1984; MacIlroy and Kee 1986; MacIlroy 1986; MacIlroy 1990). Evidence for the station house, tryworks and workshop/boatshed, storage cave, jetty and a contemporary boat–builder's workshop has been excavated and recorded, although no analysis of artefacts removed during excavation has been made.

Figure A8 ‘View of the Tunnel under the Round House and Whaling jetty at Fremantle’, 1840s by Horace Samson. (Personal collection, Mrs. Godbehear, Perth).

127In several respects Bathers Beach is atypical of Western Australia whaling stations. The substantial brick foundation of the tryworks shows three hearths, significantly larger and more elaborate than any of the other tryworks located (Figure 4.14). This structure and the other substantial capital works are indicative of the grandiose intentions which characterised the earliest phase of whaling. However, despite their ambitions the parties of the Fremantle Whaling Company and later lessees never exceeded four boats. Although the largest and most elaborate of the Western Australian shore stations, in comparison to many other Australasian whaling parties this would still have only been rated as a modest establishment.

CARNAC ISLAND

Date range: 1837, 1845, 1853–c.1875

Location: East bay of Carnac Island, 10 km southwest of Fremantle. Precise location unknown.

1:100,000 AMG Reference: 2033 Fremantle 739–452

History

In 1837 the Northern Whaling Company, also referred to as the Perth Company or Carnac Company, established a shore whaling station on Carnac Island in competition with the Fremantle Whaling Company at Bathers Beach. The company was based on joint stock investment of £600, with 20 men, three whaleboats and a jolly boat (SRG 4/5/1837). Reports at the time suggest that the station was located in the sheltered eastern bay (SRG 4/5/1837) and that a jetty, residence and store were under construction (PG 6/5/1837). The store was constructed from the frame of the former first church in Perth, known as the 'rush church', which was purchased at auction for £25 (PG 15/4/1837).

As described in Chapter 2 the 1837 season proceeded very badly and at its end the company decided to dissolve, auctioning its equipment (PG 10/2/38; PG 17/2/38). However, when the company tried to offer the station and its seven year lease back to the government ‘with all improvements thereon, for a reasonable consideration’, they were reminded that upon dissolution of the company the land and buildings had automatically reverted to the Crown (PG 24/3/38). The company was formally dissolved on May 23 (PG 26/5/38).

In 1845 Captain Anthony Curtis attempted to establish a new station on Carnac (Cammilleri 1963), combining it with the use of his schooner Vixen to cruise the adjacent islands (PG 12/7/1845). Statham (1980) suggests that the effort of transporting supplies to Carnac and difficulties in hiring and retaining crews made the venture uneconomic, forcing its closure at the end of the season. The next occupation was more successful, with Joshua Harwood basing his whaling operations on the island from as early as 1853 (CSR 344/244: 24/5/1856). Details on the station are extremely limited, although it is probable that a schooner or other small vessel would have been used for transporting supplies, if not to assist with the whaling itself. A condition of Harwood's lease was that he kept the government quarantine buildings on Carnac in good repair, which suggests he may have been using them to house his crews.

The final year in which Carnac Island was used as a base for whaling is uncertain. Although ‘Harwood's party’ is last mentioned in 1860 (PG 19/10/1860), there is the possibility that Carnac was one of the unidentified ‘Fremantle’ stations reported operating until 1875.

Site Description

Carnac Island is a small limestone island of about 2.5 hectares in area, situated 10 km southwest of Fremantle. Although normally accessible by small boats, two attempts to reach Carnac Island to carry out a survey for this project were unsuccessful. No reports have been made of evidence for early occupation being found on the island.

From the limited historical evidence it is most probable that the successive whaling stations were situated in the sandy bay on the east side of the island. Adjacent limestone hills provide further wind protection and a vantage point for a look–out (PG 15/7/1837), giving a view to the area between the island and the mainland (Gages Roads and Cockburn Sound), and out to sea.

ROTTNEST ISLAND

Date Range: 1850

Location: Thomson Bay, east side of island, 18 km west of Fremantle. Precise location unknown.

1:100,000 AMG Reference: 2033 Fremantle

History

The earliest proposal to use Rottnest as a base for whaling activities was in 1832, with John Sweetman (Swetnam) being given approval to occupy land for that purpose (CSF 5/99: 17/3/1832; Erikson 1988:2996). The venture never proceeded, with the island being declared an Aboriginal prison several years later with all land grants revoked and whaling parties warned to stay away (Ferguson 1986; CSR 19/236: 29/7/1845).

The first and only attempt to form a whaling establishment on Rottnest was made in 1850, during a brief period when the island was not being used for penal purposes. James Dempster obtained the lease of the island including pastoral rights, use of the salt works and permission to form a whaling station (PG 21/9/1849). Dempster made arrangements with both Bateman and Harwood for use of whaleboats and equipment (Inq 19/9/1849). Local newspapers reported 128on his preparations for a three–boat fishery and wished him luck, but feared there were many obstacles to his success (PG 5/7/1850; Inq 10/7/1850). One major impediment was that despite two recruitment drives, local whaling hands were reluctant to join his party because it would mean they were isolated on the island for months. His party chased a humpback in late September before conceding defeat (Erikson 1978). Five years later in 1855 Rottnest was again declared a prison with no boats allowed to land there (GG 12/8/1856).

Site Description

Rottnest Island provides a good location for a whaling station, commanding both the area about Gages Roads and the seaward side of the island. Dempster and his men used existing buildings on the island, many of which are still standing and in use (Ferguson 1986). It is probable that the tryworks was located in Thompson Bay, the sandy, eastern facing bay on which the settlement is situated. The adjacent limestone headlands would provide excellent vantage points for a look–out. Unfortunately the short duration of the party, the fact that the tryworks was never used and the subsequent heavy use and remodelling of the foreshore has removed all trace of whaling activity.

SAFETY BAY

Date Range: 1838

Location: Approx. area would be the northern end of Warnbro Sound, 30 km south of Fremantle.

1:100,000 AMG Reference: 2033 Fremantle

History

In 1837 the American whaler Pioneer spent several months bay whaling in Warnbro Sound and surveying the harbour (PG 26/5/38; Ogle 1839: 243). In the following year the master of the vessel entered into a partnership with local landowner Thomas Peel (see Chapter 1; Hasluck 1965). In the same year the Western Australian Whaling Company was reported as establishing a station in Safety Bay at the northern end of Warnbro Sound. The company made claims towards establishing an ambitious bay–whaling venture, but probably failed to obtain adequate capital (PG 8/7/1837; PG 15/7/1837). A measure of this was that at the start of the season they had to refute claims that they did not have the means for catching and processing whales, or even for provisioning their men (PG 5/5/1838). There is no description of the progress of this party until October, when no return is given for "Duffield's party", despite the Pioneer taking 35 tuns of oil (PG 20/10/1838).

Although the nearby Fremantle Whaling party complained about foreign intrusion (CSR 61/14: 9/5/1838), the lack of complaint from the Western Australian Whaling Company suggests the possibility that they too entered into the co–operative arrangement described above. This agreement would have provided the company with the means of overcoming their difficulties with capital and equipment, as well as providing experienced hands for the fishery (PG 5/5/1838). Ironically, if this were the case, it contrasts with an early account of their prospectus, which claimed that no foreigner would be allowed to hold interest in the company (PG 22/7/1837). There is no evidence that Safety Bay was subsequently used by either colonial or foreign whalers. A final mention of the station appears in November 1839 when newspapers reported a dispute between the station owners and the former cook about whether the latter had agreed to work for a lay or wages (PG 31/11/1839).

Site Location

Safety Bay is the northern end of Warnbro Sound, a large bay fringed by a limestone reef which provides some protection from swells and high seas. The point at Safety Bay is a relatively low limestone outcrop and sand dune, although the hills on adjacent Penguin Island might have provided sufficient elevation for a look–out across the sound and adjacent seas. The beachfront area has been remodelled for recreational and residential purposes and no evidence has been found of whaling activity. It should also be considered that the 1838 arrangement with the American whaling ship may well have obviated the need for a shore–based processing plant or other buildings.

BUNBURY WHALING STATION

Date Range: 1838– c.1867

Location: Precise location(s) unknown, although probably along the east side of Point Casuarina (Koombana Bay), in the area of the small boat harbour.

1:100,000 AMG Reference: 2031 Bunbury 731–126 (approx. only)

History

During 1838 several reports appeared regarding the whaling potential of Koombana Bay, enhanced by the successes of Americans bay whaling there (PG 21/7/1838; PG 20/10/1838). By July of that year a small colonial ‘tonguing’ party salvaging the discarded portions of the whales had already recovered seven tuns of oil (PG 14/7/1838). In the following season the local settlers formed their own shore–station, although there are no reports on its nature other than it was making satisfactory progress (PG 6/7/1839; PG 10/8/1839).

No colonial party was formed in the next several years despite increasing American activity, with one reliable source reporting 14 vessels seen in a single day (Clifton 1841). The wreck of three American vessels in the bay during a gale in mid–1840 saw the captains auction off hulls and equipment (Table 2.1; Henderson 1291980). One of the captains (Coffin) spent the remainder of the 1840 season with his crew bay–whaling (PG 1/8/40), although it is not known whether they established a shore station or continued to use one of the wrecked ships as a base. The colonial government also made legal attempts to limit possible foreign interference with any colonial party which might arise (CSR 85/82: 21/4/1840).

In April 1843 another American whaleship was driven ashore in during a gale, selling its equipment to J.K. Child who was forming a whaling party (PG 22/4/43; Inq 3/5/1843). The arrangement seems to have included some partnership, possibly with the captain, with a contemporary diary recording Child was

enabled to enter into the bay–whaling by taking an experienced American into partnership, and he sees after all the work; the men are also paid by shares in the oil (Burton 1954:272).

Reports during the season showed the station achieving some success but also losing a number of whales, possibly through inexperience (Inq 26/7/1843; Inq 13/9/1843). Despite this, Child continued in the following year, now competing with The Koombana Bay Whaling Company, headed by John Scott (PG 11/5/1844). Child applied for and was granted the lease of an area of land on which to erect whaling buildings, with the Koombana Company granted the area immediately west (CSR 131/1: 1/2/1844; CSR 131/4: 8/2/1844). Both groups were moderately successful, although there were reports of competition (PG 27/7/1844). There was also friction over the Koombana Company's decision to take up an offer of assistance from two American vessels, offered by the latter as a means of being allowed to remain along the coast (CSR 131/59: 31/7/1844; CSR 131/60: 29/7/1844).

Throughout the 1840s and 1850s Koombana Bay hosted one or more colonial shore stations, operating under various owners and managers. It is uncertain if the same station sites were re–used over time, although at least one letter records that Child's original buildings were removed in 1847 ‘for the police station’ (CSR 24/118: 4/12/1847), while another states that the boards of the ‘whale house’ were being re–used in a stable (CSR 24/313; 29/4/1848). In 1849 Messer’s Onslow and Sillifant formed a new company which allowed their men to resided in their own homes, meeting only for business. The proceeds of the season, presumably increased by not having to meet the overheads of providing food and accommodation, were then divided among the men (Inq 30/5/1849; Inq 12/12/1849). The scheme worked well and the same group continued in 1850, although operations were hampered by difficulties with a new harpoon gun (PG 22/11/1850).

In 1855 John Bateman commenced his practice of sending a small party to one of the southwest stations, usually in September after the season had closed at Port Gregory. Although given permission to build his own tryworks (CSR 366/169: 11/3/1856), Bateman eventually leased the existing whaling buildings at Bunbury for a sum of only £1 (CSR 366/182; 22/4/1856), waiting until 1862 to build his own station (CSR 502/260: 6/8/1862). Sometimes in competition with local parties, Bateman's crews continued to visit Koombana Bay during most years until at least 1867 (Her 5/10/1867). In 1870 his weatherboard station house and tryworks were removed (CSR 645/112: 28/6/1870), possibly to Castle Rock where he continued operations.

Site Description

The historical record describes a succession of whaling stations constructed along the shores of Koombana Bay, presumably beneath Marlston Hill (also known as Lighthouse Hill) which provided the look–out point (Mitchell 24/3/1927).

An undated but possibly 1843 plan of Bunbury by John Wollaston (Poole 1979: 225; Parks 1990) shows several foreshore buildings noted as "Child's Buildings" close to the end of what may now be Eliot Street. However, the 1844 lease agreements (CSR 131/2: 18/1/1844), which placed the Koombana Company's lease as west of Child's station, suggests that both stations were probably further north of this, along what is described on the Wollaston map as ‘The Strand’. Later reminiscences also suggest this area, facing out onto the bay proper, as the location for Bateman's station. The first report (Mitchell 1927) states that it was ‘near the present breakwater’, while another (Anon 1936) says that the ‘old whalehouse’, stood on the foreshore ‘just a little the other side of where the jetty baths are now located’.

Various accounts from the 1840s onwards describe the demolition or removal of successive whaling station buildings, most of which appear to have been wooden, and were subsequently re–used. Harbour works on the Bunbury foreshore, including extensive land reclamation has substantially altered the topography of the probable area of the whaling stations. No surface evidence was located, although it is possible that remains are buried below later fill.

MININUP

Date Range: 1862–63+

Location: Possibly adjacent to Mininup Hill

1:100,000 AMG Reference: 2031 Bunbury

History

In 1862 Joseph Buswell registered a whaling party for ‘Bunbury and Minninup’ (GG 19/8/1862) and in the following year for ‘Minenup, or elsewhere in the Wellington District’ (GG 15/9/1863). There are no contemporary descriptions of this party's operation, although the Blue Books report that in the first year only one tun of oil was taken, with only 5.5 tuns in the 130second (BB 1862, 1863). A later account from a local octogenarian suggests that unregistered parties may well have continued whaling from this location on an irregular basis.

When work for the men was slack on the farms and dairies, the settlers around Mininup combined and started whaling, but not with very great success. Mrs. Rose relates that a man with a spy glass was stationed on the highest hill near this place and also one on the Lighthouse Hill in Bunbury, who gave the alarm "Whale–ho!" or "Blow–ho!" whenever a whale was sighted. The boats would then be manned in a very short time and give chase. (Mitchell 1927)

It is possible that faced with the competition of Bateman's crews, it was hoped that a station at Mininup would sight and catch the whales before they proceeded north to Koombana Bay. However, as Buswell occupied Mininup House during this period (Erikson 1988: 417), the location of the station near to his holdings can be seen as an attempt to diversify from other pastoral or agricultural activities. An interesting report on smuggling in the colonies (Inq 8/5/1850) also states that ‘Menninup’ (sic) was one of the locations where American whalers would drop their illicit cargoes, being close to Bunbury, yet far enough away to escape detection.

Site Description

The area which is generally known as Minninup is approximately 19 km southwest of Bunbury, although no historical description has been found which provides a precise location for the Mininup whaling station. Adjacent to Minninup Homestead is a shallow cove backed by high dunes which is still used as an anchorage for small boats, and is the most likely position for the station. Several weatherboard buildings and sheds are situated in a gully between the sand dunes, immediately behind the anchorage. No evidence of whaling activity was located, although it is possible that evidence may be located on the private land behind the coastal reserve.

While not situated in a bay, Minninup provides several topographic features (anchorage, high dunes) which fit the pattern for whaling stations elsewhere on the west coast. The location is another compromise site, attempting to avoid direct competition with the Bunbury station, but also one of the few obvious attempts to combine whaling with the pastoral and agricultural interests of the adjacent hinterland.

TOBY INLET

Date Range: 1847

Location: Precise location unknown, but approximately 17 km west of Busselton.

1:100,000 AMG Reference: 1930 Busselton 309–759 (approximate only)

History

The operation of a shore station at or near Toby Inlet appears to have been limited to a single year, and then only appears in the historical record as a result of the fatalities which the party suffered during the season. In August 1847 it was reported that a Right whale taken by the Castle Rock party had previously been fastened to by the whale boat of another company which had come to grief (Inq 25/8/1847). After being struck by the headsman of this latter boat, the whale was said to have gone quietly for the first 400 yards, after which it turned and stove in the side of the craft, drowning three of the crew.

Little more is known of the station or its operation. Late in 1847 a summary of returns from the fisheries refers to ‘Mr. Kerr's’ party, but gives no location or quantities (PG 6/11/1847). As a Mr. H.T. Ker was known to be the manager of John Molloy's property which borders Toby Inlet (Erikson 1988: 1732), the connection with the whaling party appears certain. A pamphlet from the Busselton Historical Society, which states that the party consisted of only one boat, and that the drowned seamen were buried ‘beneath the peppermint trees near Toby's Inlet’ (Anon 1977). An alternative secondary source suggests that the bodies were buried ‘under the peppermint trees near where Seymour's old cottage used to be in Dunn Bay Road’ (Guinness n.d.:24), a considerable distance away in Dunsborough itself.

In 1846 another shore party, unrelated to Ker's venture, had also competed with the Castle Rock fishery from somewhere in Geographe Bay. The location of this station has not been identified, although it is possible that it was based at Toby's Inlet.

Toby Inlet held some significance in the early history of the area as the closest watering point for vessels visiting Busselton, there not being a supply readily available near the beach at the town itself. As a result, this became one of the points where both legitimate and black market transactions took place between settlers and visiting American whaleships (Inq 8/5/1850).

Site Description

Toby Inlet is located about 17 km west of Busselton and 10 km south–east of Castle Rock, opening onto the flat, sandy beach that forms the long curve of Geographe Bay. The area is an unlikely choice for a whaling station, exposed to the open sea without a headland or 131high dune for weather protection or look–out point. Toby Inlet itself is shallow and cannot currently be entered by boats, although it is possible that this was not the case in the 19th century.

In the absence of historical or topographic indicators which locate the station, the beachfront and adjacent vegetation were surveyed for 100 m to either side of the mouth of Toby Inlet. No surface indications were found.

The area about Toby Inlet contains virtually none of the topographic characteristics seen at whaling station sites elsewhere along the west coast. The main factors in its selection would seem to be the proximity to an existing land grant (Molloy's property), the need to operate outside of the lease boundaries of the adjacent whaling station (Castle Rock), and availability of fresh water (Toby Inlet).

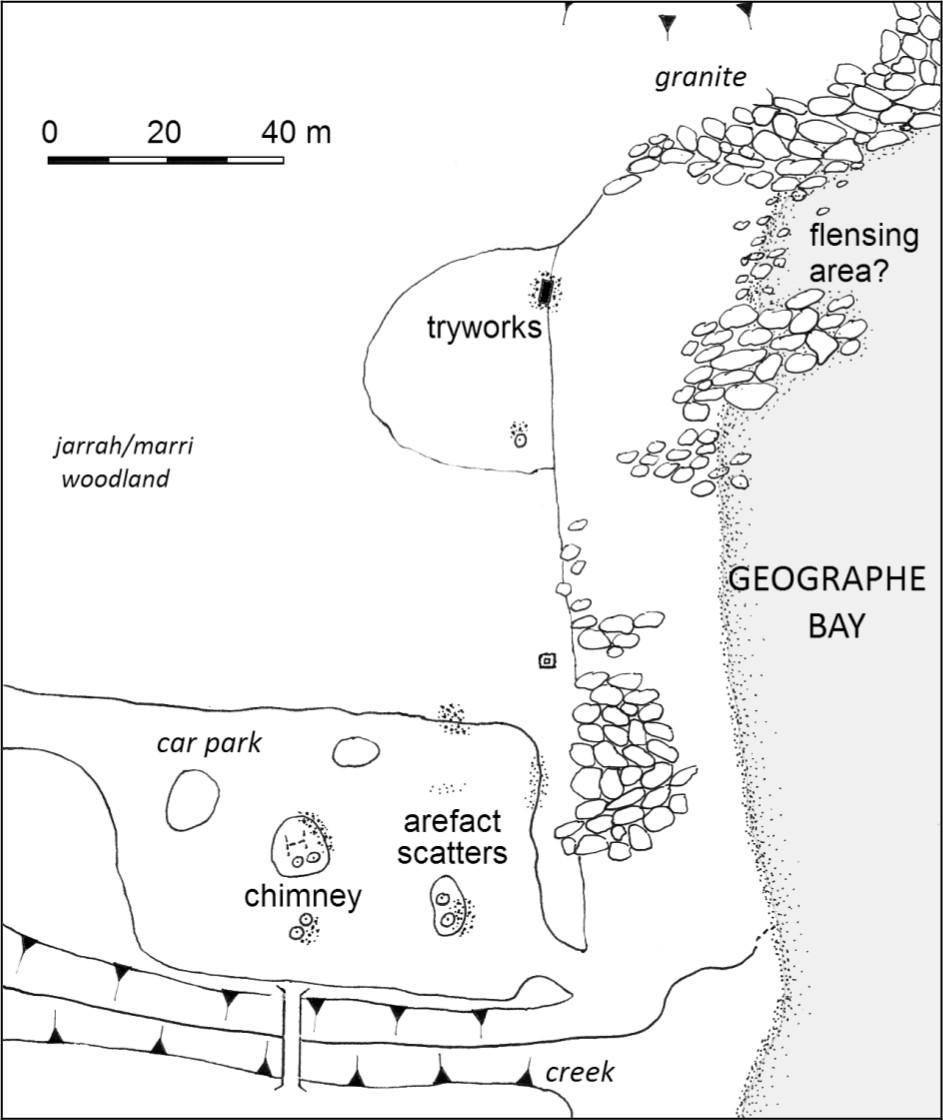

CASTLE ROCK

Date Range: 1846–c.1872

Location: 25 km northwest of Busselton, between Sail Rock and Castle Rock.

1:100,000 AMG Reference: 1930 Busselton 231–826

History

The first colonial party was established at Castle Rock in 1845 after consistent use of the area by American vessels who had also reported on the potential of the site for bay whaling (Hasluck 1955; 212). Robert Viveash's 1845 lease of three miles of shoreline southward from Castle Bay as well as the adjacent pastoral land appears to have been aimed at excluding a rival colonial shore party from access to this area (CSR 140/107: 20/9/1845). Initially the lease payment was set at a staggering £40 for the 1845 and 1846 seasons, although this was later lowered to £30 after Viveash reduced the area of land under lease (CSR 140/108: 20/9/1845; CSR 140/110: 1/11/1845; CSF 19/392: 19/11/1845). In the following year the station operated again as the Castle Rock Whaling Company, possibly made up of a partnership of Viveash, Robert Habgood, Robert Heppingstone and Robert Sholl, all of whom are mentioned in connection with the station at various times (Seymour nd; PG 22/8/1846).

After 1847 Robert Heppingstone and George Chapman, took over management of Castle Rock. Heppingstone died in 1858, with his son–in–law George Layman then running the station until 1860 (SDUR L3/299: 18/3/1859). As described in Chapter 3, the diary of manager (and headsman) Frederick Seymour provides a daily record of the station’s proceedings for 1846–53. During this time Castle Rock was a moderately successful small–scale fishery with two or sometimes three boats.

In 1861 a new partnership controlled by the Bunbury whaler 'Butty' (Maori headsman William Parr) and local land owner George Bridges, was listed as operating at Castle Rock (Erikson 1988:306; PG 21/8/1861). This lasted only a single year, followed by a hiatus in use until the late 1860s, when John Bateman decided to relocate his late season fishery from Bunbury. The exact date when Bateman commenced to visit the station is uncertain, although the first confirmed use is in 1871 (Herald 16/9/1871). The last recorded occupation by Bateman is a year later, with the catch of only five tuns of oil (Herald 30/11/1872).

Figure A9 Castle Rock Site plan.

There are several reports over the years of Castle Rock parties using small vessels to assist operations (see Chapter Three). In 1847 Heppingstone arranged the hire of the newly–launched Gazelle to work with the shore party (Inq 4/8/1847), although this ship is not mentioned in Seymour's journal or subsequent news reports. In October 1848 Seymour (n.d.) notes the Sonnet Bee arriving to help ‘cut–in’, while in the following year the Pelsart came down from Fremantle to meet with Chapman's group (Inq 24/10/1849). George Layman is also known to have purchased the cutter Brothers in 1859 for use as a cutting–in vessel (Inq 25/5/1859), while Bateman would have also used his schooner Twinkling Star for a similar purpose (Herald 16/9/1871).

Despite Seymour’s diary there is very little information on the physical nature of the station. The earliest reference is from March 1849, when it was reported that a bush fire had destroyed Heppingstone's whaling establishment. The loss of the whole of his gear, one whaleboat and all of the bone was estimated at several hundred pounds value, although the oil, presumably stored separately, narrowly escaped damage 132(Inq 28/3/1849). It may have been in consideration of this situation that Heppingstone was allowed the lease of Castle Rock free of charge that year (CSF 27/205: 1/8/1849). The second reference is from 1871, when John Bateman was granted permission to erect at Castle Rock a two–roomed portable house for his whaling crew (CSR 9/6/1871). It is not known if the house was removed by Bateman at the end of his use of the station.

Site Description

Castle Rock is a relatively small, northward–facing sandy cove between granite outcrops, unlike the coastal formations seen elsewhere along the lower southwest coast. On the hill above Castle Rock is a white–painted granite boulder locally known as Lookout Rock, reputed to have been used by the whalers and more recently by salmon fishermen (Guinness n.d.). From this point there is an extremely wide view, both northwest into Castle Bay and southeast into Curtis Bay and Dunn Bay. A more accessible look–out with similar, if somewhat more limited views is from the top of Castle Rock, situated to the east of the site.

The site of the Castle Rock whaling station is well known and has been marked by a cairn and plaque erected in 1969 by the Royal Western Australian Historical Society. Several archaeological features still remain, although as a popular fishing and swimming place many of these have been destroyed through various processes. The habitation area was located on the west side of the winter creek, in the space now occupied by the car park. The foundations of at least two buildings were intact until the mid 1970s and at least one of the structures was floored with whalebone (J. Lord pers. comm. 1989). Several pieces of the vertebrae paving were rescued by the Busselton Museum after the local council graded away the remaining structural features to form the car park. Small scatters of highly fragmented ceramics and glass are still visible within this area, although no diagnostic pieces could be located. These artefacts, including some pieces of brick, worked stone and mortar are closely associated with the raised islands of soil surrounding the trees and vegetation left standing within the car park. The most substantial of these is a low mound located on the south end of the car park (furthest from the beach). While only several meters square in area, this appears to contain a fairly substantial section of masonry, possibly a chimney base.

The foundation of the tryworks is located approximately 60 m west of the memorial cairn, at the juncture between the beach sand and soil. Located well above the high–tide mark, the structure is of stone and brick, and of sufficient size to take two trypots (see Figure 4.9). There is no evidence of a covering structure. The flensing area was probably to the northwest of the tryworks, in or just beyond the clear area between two concentrations of boulders. There is no evidence for a ramp or platform, although the expanse of beach would require some sort of surface for winching the blubber to the processing area.

The tryworks were cleared of vegetation and surrounding earth during the 1987 National Trust survey, and the main dimensions recorded (MacIlroy 1987). This loose overburden was removed again in 1990, with the structure drawn and a sample of the ash removed from both hearths.

SOUTH COAST SURVEY

The south coast of Western Australia is characterised by large granite outcrops which form mountains, headlands and islands. The action of heavy southwest swells and easterly littoral currents upon these granite hard points has resulted in the formation of numerous crescent–shaped sandy bays which open towards the east (Woods 1980). Tidal variation is likely to be less than one meter.

Figure A10 South Coast whaling stations.

The climate west of Doubtful Island Bay experiences a Moderate Mediterranean climate with cold and wet winters peaking in July–August. To the east around Cape Arid the climate is classified as Dry Mediterranean, with six or more dry months each year. On the coastal fringe itself, the cold winds, rain and squalls blowing in from the Southern Ocean during the winter months can make maritime work difficult.

TORBAY/ MIGO ISLAND

Date Range: 1844–1848, 1861–c.1864

Location: East side of Torbay, slightly NW of Migo Island.

1:100,000 AMG Reference: 2427 Albany 587–188

History

In 1844 a shore station was established in Torbay by John William Andrews (sometimes referred to as Williams), a sealer who had also previously conducted a whale fishery in Two People's Bay. During 1844 the 133operation employed Andrews' schooner Vulcan and two whaleboats, taking six tuns of oil and 500 pounds of bone worth £133 (Heppingstone n.d. b). In 1845 John Sinclair was granted the lease of Migo Island as his whaling establishment at an annual fee of £5, a move supported by the local Resident Magistrate as a means of excluding Andrews and his ‘convict party’ from the area (CSR 139/61; 20/5/1845). An appeal was made that the fee be lowered, clarifying that the island was only intended to be the look–out for the station (CSR 139/37; 20/3/1845), with the fee eventually lowered to £1.10s (CSR 139/61; 20/5/1845). During the season Sinclair used his boat Julian (Garden 1977), although no returns were reported to judge whether the party was successful.

Sinclair renewed his lease for the following year and left his trypots in place in anticipation (CSR 139/119; 14/11/1845; CSF 19/408: 2/12/1845). However, only Thomas Morton with his schooner Thetis is specifically mentioned as being at Torbay during the 1846 season (PG 5/9/1846), although one report does refer to ‘the parties [my emphasis] stationed at Torbay’ (PG 12/12/1846). The Thetis was recorded as taking 25 tuns of oil, three of which were sperm oil (PG 12/12/1846). Andrews may then have occupied the station in 1847 (CSF 23/208: 4/6/1847), with Sinclair possibly using it in 1847 (Heppingstone nd. b).

Torbay was next occupied in 1861 when Hugh McKenzie registered a party of 14 men for a two boat fishery (G.G. 18/6/1861). The season was either brief or unsuccessful, as the Blue Book (1861) records a total take of only two and a half tuns of oil (probably a single whale), worth only £90. There is no record of operations in 1862, although in 1863 and 1864 McKenzie organised a two–boat party, taking eight tuns and 18 tuns of oil in the respective seasons. A report from 1864 suggests that several tuns of oil had been lost through lack of a second trypot (Inq 16/11/1864). The location does not appear to have been used after 1864.

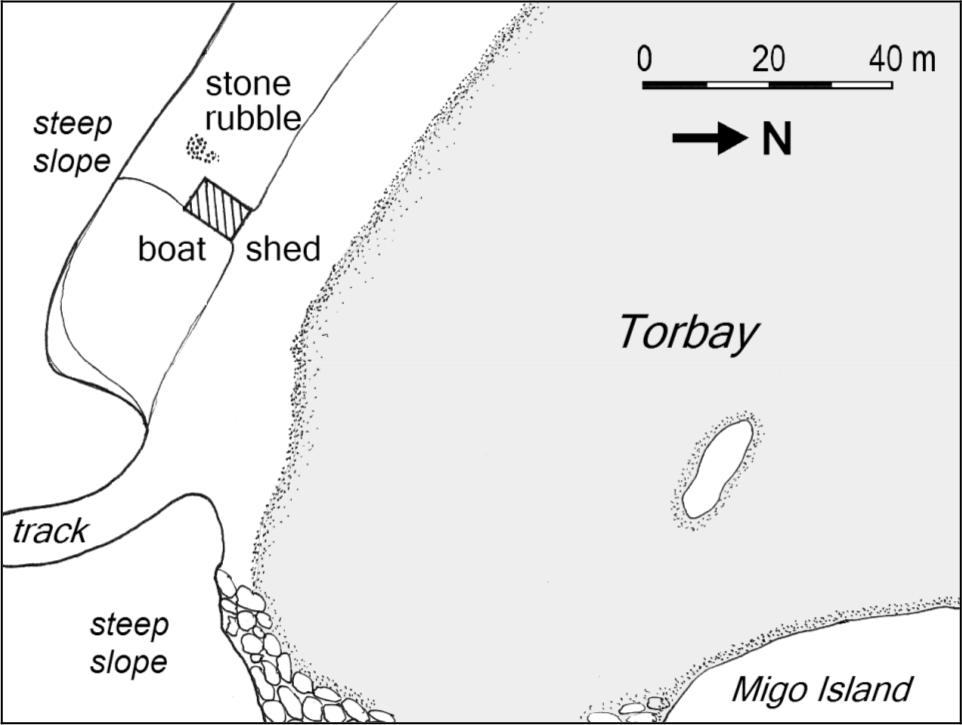

Site Description

Migo Island is a drowned granite mass in the northwest corner of Torbay. The island and an adjacent headland protects a strand of beach on the mainland, although this area is backed by a very steep ridge. The 1987 survey (MacIlroy 1987) located a stone feature on the mainland shore slightly northwest of Migo Island, at the foot of the ridge and close to the current landing area. The removal of covering vegetation and earth suggested that this was granite and mortar rubble from a structure, although no diagnostic artefacts were found which could positively identify this as the whaling station site. When re–inspected in 1989 and 1993 the area was heavily overgrown with limited visibility. The rubble covers an area of approximately 2 m2, although in 1989 it was noted that further mounds or raised areas of earth and scatters of unmortared stone, possibly natural expressions, continued to the northwest. However, the lack of a clear pattern or distribution of the stone suggests that this material may have been pushed aside several meters by a bulldozer or other means to create an adjacent cleared area used by modern fishermen. No surface artefacts were seen.

The small beach where the stone material is located is on the lee side of Migo Island and sheltered from Southern Ocean swells, while the adjacent ridge provides further protection from wind and rains. Other than the beach itself, there was no location in the immediate area suggestive of a flensing or processing area. It was not possible to visit Migo Island to investigate evidence for look–outs, although the peak would provide good visibility throughout Torbay.

Figure A11 Torbay site plan.

An 1837 survey plan of Torbay shows a small building labelled ‘Shipbuilder's Hut’ in the approximate area of the site (Broeze and Henderson 1986:60). Immediately next to this are two parallel lines of points marked ‘A vessel of 150 tons on the stocks here’, almost certainly the vessel constructed for T.B. Sherratt (PG 14/4/1838), while nearby are further notes including ‘sandy beach’ and ‘good water’. It is clear that prior to the whaling period the area was a known anchorage and already in use by colonial entrepreneurs. It is possible that the structural remains are associated with the early shipbuilders, the whalers, or both. Subsequently Torbay has been a centre for timber milling, boat–building and fishing, with the area of the site including a dilapidated modern fishing shed and the remains of segments of old railway line possibly formerly used to slip boats.

BARKER BAY/ WHALING COVE

Date Range: 1849–c.1873

Location: Whaling Cove, west side of King George's Sound, 5 km southeast of Albany.

1:100,000 AMG Reference: 2427 Albany 845–201

134History

It appears that James Daniells, a publican in Albany, had already commenced the 1849 season with a one boat fishery elsewhere in King George's Sound before he decided (or was forced) to apply for a lease of land on which to form a station

situated in Barkers Bay on the west side of King George's Sound, with about (20) twenty chains water frontage having a shelving rock above the centre running into the seas. And I also beg to apply for the lease of Mistaken Island to run a few sheep on for my establishment (CSR 189/249: 16/8/1849).

The Resident Magistrate supported the application, suggesting purchase or a long lease would allow Daniells to erect tryworks and buildings for his men in a substantial manner suitable for a permanent station (CSR 189/250: 26/8/1849). Although the land could not be sold because of its strategic value, the government allowed a seven year lease, renewable annually provided he occupied the site during the whaling season (CSR 189/247: 12/9/1849).

The King George's Sound station, presumably the Barker Bay site, is noted in various records as operating continuously between 1849 and 1852. A hiatus of several years follows in which there no mention of the station, until 1856 when several reports which suggest there was a party in the area (Inq 15/10/1856; BB 1856). In 1857 the station commenced operations under the control of Thomas Sherratt (Inq 15/7/1857), the son of Thomas Booker Sherratt who had operated at Doubtful Island Bay in 1836 and 1837. It is uncertain whether Daniells also maintained an interest in this party, as there is correspondence from him regarding a lease of Mistaken Island as a station (CSF 41/543: 10/8/1857). Alternatively, it is possible that he attempting to form his own party.

Sherratt occupied Barker Bay consistently until at least 1872, using it as his early season station before proceeding eastward to Barrier Anchorage. In 1872 he sought to renew his lease on both Barker Bay and Barrier Anchorage, once again describing the areas (BL Acc. 346 (14/73): 8/5/1872). The extent of the lease (Plantagenet license 928) had increased slightly in size from the original, taking in about 25 chains (502 m) of shoreline and 22 acres (9 ha) in area.

Besides the station at Barker Bay, several sources suggest associations with Mistaken (Rabbit) Island, and the use of the island to hold sheep for the station has been described above. In 1850 there is a report of a whaling party formed at Mistaken Island (Inq 31/7/1850), as well as Daniells’ 1857 inquiries. Reminiscences from Sale (1936), McKail (1927) and Chester (1927) all speak of whaling activity in connection Mistaken (Rabbit) Island, especially use of the island as a look–out. However, it is difficult to determine if the site was a separate station from Barker Bay.

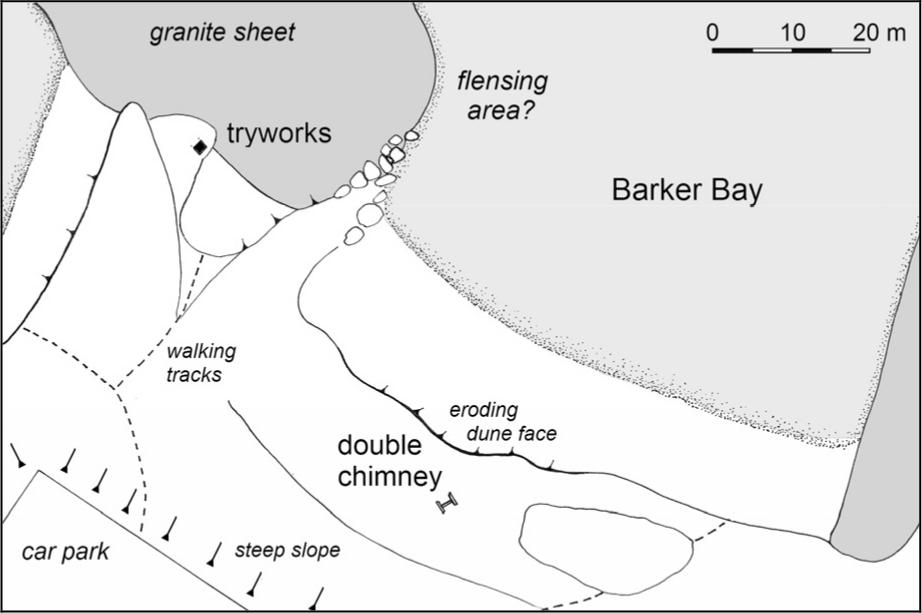

Site Description

The Barker Bay site retains structural evidence for both the processing and habitation areas of the whaling station. Fifteen 50 cm by 50 cm test–pits were excavated around these two zones to determine whether the archaeological deposits would be suitable for the more extensive excavation intended for this project.

The bay consists of a sandy beach between granite points, backed by sand dunes and a high ridge. The tryworks is located on the southern side of the sloping granite sheet forming the western edge of the small bay. Presumably the whale would be anchored in the water adjacent to this platform, and the blubber winched over the rocks to the trypot(s). The tryworks structure is reduced to a granite base measuring approximately 3 m by 2 m, situated at the juncture of the granite and the vegetation line (Figure 4.12). Within it is the solidified black organic deposit seen in other tryworks. Several test pits around the area of the tryworks produced a quantity of iron barrel hoops strapping. Other artefacts including clay pipe fragments were present on a eroding dune 15m east.

Figure A12 Barker Bay Site Plan.

On the dune ridge above the beach (now seriously eroded), sit the remains of an east–west facing stone built double fireplace, although no other evidence for walls or other structures is visible. Small test pits to the west of the fireplace revealed a stone floor surface, although the full dimensions were not established. Artefacts recovered from test pits adjacent to the structure included were largely undiagnostic 19th century glass, ceramic and faunal material, apart from a clay tobacco pipe stem stamped with ‘MURRAY’ ‘GLASGOW’ confirming a date range of 1830–1860 (Oswald 1975:205). Interviews with local residents suggested that various artefacts have been recovered as they erode out of the dune surfaces.

The headland to the east of Whalers Cove would provide a view across King George's Sound, and possibly into Frenchman's Bay itself. However, there is no immediately visible feature which suggests a look–out 135out point and a survey of the hillside did not reveal any structural or other archaeological evidence.

Although the beach immediately west of Mistaken Island was also briefly surveyed, no evidence was found to suggest possible use as a whaling station. The location provides some advantages with its outlook over King George Sound and Frenchman's Bay, with the disadvantage that the area is more exposed to winds and swells than Barker Bay. Slightly to the northwest of Mistaken Island is a sloping granite slab which might have suited as a flensing area, while south of this are sandy beaches which are afforded some slight shelter by the island and the reef which stretches between it and the mainland. These attributes make the location suitable for use, while it is possible that the clearly evident storm action has removed physical remains from the area.

TWO PEOPLES BAY

Date Range: 1842–1844, c.1870s

Location: North side of King George Sound, south end of Two People Bay, 34 km west of Albany.

1:100,000 AMG Reference: 2528 Manypeaks 083–295

History

In 1838 and 1839 a combination of American, French and Australian whaling vessels took catches of whales from within Two Peoples Bay yielding at least 650 tuns and well over 1000 of oil (PG 28/7/1838; PG 24/11/1838; PG 1/12/38; PG 17/8/1839; CO 18/26: 30/6/1840). Colonial use of the location dates from 1842, when James William Andrews requested protection for his fishery from foreign whalers (CSR 111/152: 2/5/1842). Despite the uncertainty regarding colonial powers to restrict foreign whaling, a letter was issued warning non–British ships that persons interfering with the colonial party or whaling within three miles of the coast would risk forfeiture of their vessel.

Little is recorded of the 1842 or 1843 season, although a second letter of protection issued in the latter year describes it as consisting of four boats and 30 men (CSR 119/98; 22/6/1843). It is possible that Andrews was using his vessel Fanny (PG 8/10/1842) or in the latter year the Vulcan (Garden 1977) to assist operations. Exports through Albany in 1843/44 included 13 tuns of whale oil and 700 pounds of bone, which could only have come from the Two Peoples Bay station (Garden 1977: 79). Another interesting feature is the 1843 census of Albany, which recorded a population of 260 persons, including 16 Americans employed at Two Peoples Bay (Glover 1952: 119).

Andrews moved his whaling operations to Torbay in 1844 (Heppingstone n.d. b) leaving another unidentified local party to form a station at Two Peoples Bay (Inq 6/11/1844). While an un–named brig from Tasmania was reported as taking 1000 barrels of oil in the bay, the local party took nothing, with several of the hands even deserting to join the Tasmanian ship (Inq 6/11/1844).

No other colonial party is reported as using Two Peoples Bay for at least the next two decades. In a set of reminiscences, Evidence for later use of the station is contained in a set of reminiscences of the 1880s and 1890s with McGaughin (1916) recounting the Grace Darling riding out a squall at the anchorage in Two Peoples Bay.

The Mackenzie Brothers once had a shore whaling station in the bay, and near a shallow fresh water swamp we came across evidences of their sojourn, the rotting remains of a whaleboat, a discarded trypot, a broken steering oar, and part of a rusted harpoon.

There is no documentary evidence that the McKenzies, who commenced whaling in the early 1860s, used Two Peoples Bay as a station during that decade, preferring Torbay, Cape Riche or Doubtful Island Bay. However, it is possible that during the 1870s when parties were being registered for the ‘east coast’ (Cape Arid), Two Peoples Bay may have been used as an early season station. Webb (1963) suggests that in the 1850s Thomas Sherratt (Jnr) used the bay for whaling, but does not provide a source for this. She also states that 1873 and 1874 Mary Taylor of Candyup Station recorded in her diary several instances of men calling in en route to various whaling stations, including Two Peoples Bay. The possibility of later use therefore remains, but by which party is unresolved.

Figure A13 Two People Bay site plan.

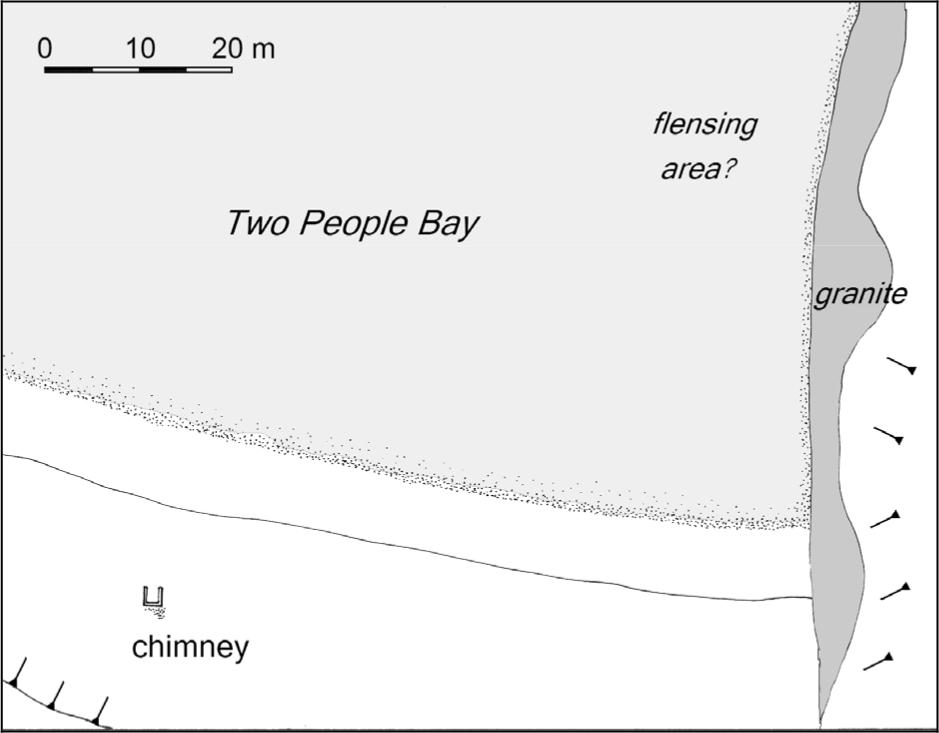

Site Description

Two Peoples Bay is a semi–circular sandy beach between granite headlands. The historical record does not indicate the precise location of the station site, 136although there are several indicators. McGaughin's (1916) account records that the remains of the station were near ‘a shallow freshwater swamp’, which would place the site just west of South Point. Alternatively, Webb (1963) states that remains could still be seen ‘at a little beach just south of the main one’. During the survey of Barker Bay, a local fisherman recalled a friend removing two trypots from Two People's Bay ‘from the little beach past the granite boulders’ (G. Brown pers. comm. 1990).

The cove located immediately southwest of South Point and separated from the main (western) beach by large granite boulders includes a protected sandy beach backed by a low, flat dune area, with a sloping granite ledge running up from the water along the east side. Survey along the vegetated dune behind the eastern corner of the beach located the base of a stone chimney base facing northwards, towards the water. The external dimensions were approximately 1.45 m along the sides and 2.25 m along the back, giving an internal area of 1.10 m by 2.35 m wide. There were no signs of other structural remains and no surface artefacts.

The higher end of the granite shelf was unsuccessfully searched for evidence for the tryworks. It is possible that vegetation cover, particularly the seaweed which has collected on the flatter areas of the ledge, had covered any structural remains. As noted, the trypots are reported to have been removed only this century, although their current location is unknown. A position on nearby South Point provides a wide view through the bay and adjacent seas and is visible from the site, although no structural or artefact evidence for a look–out could be found.

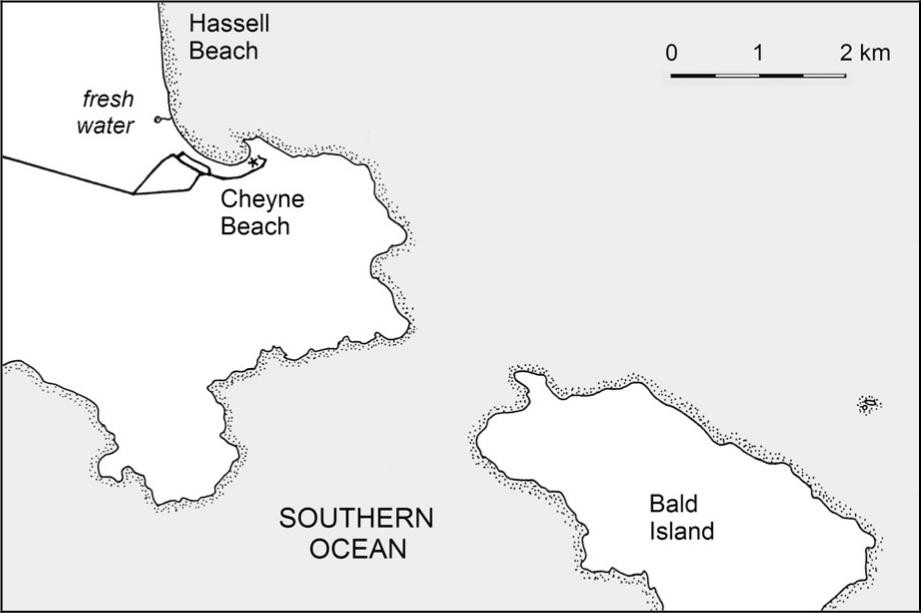

CHEYNE BEACH

Date Range: 1846–1877

Location: South corner of Hassell Beach, approximately 47 km northeast of Albany.

1:100,000 AMG Reference: 2528 Manypeaks 285–393

History

Cheyne Beach was known as a bay–whaling location for foreign vessels from at least 1840 (CO 18/26: 281, 30/6/1840), with the perennial fresh water spring 1 km NW of the headland used as a watering point.

In 1846 a whaling party was formed at Cheyne Beach through a partnership of Solomon Cook, John Thomas and John Craigie, also referred to in contemporary reports as 'Cheyne's party' (PG 3/10/1846, Inq 16/12/46). While it is possible that George Cheyne (a south coast merchant who had a whaleship supply base at neighbouring Cape Riche) held some interest in the station, this may simply be the colonial press confusing the name of the location with the man. A lease was granted for two acres of ground ‘surrounding the boat harbour’ at an annual fee of 35 shillings (CSR 149/31: 5/3/1846, CSR 149/64: 30/4/1846).

The season proceeded well, with 17 tuns of oil from eight humpbacks being taken by early August (Inq 5/8/1846), and 55 tuns of oil by early October (PG 3/10/1846). However, there were obviously difficulties in the management of the station, with Thomas going so far as to publish a notice during the following year stating that the partnership had been dissolved, and that his current whaling party had no connection with either John Craigie or Solomon Cook (Inq 14/7/1847). Thomas must have been granted the lease of the station, which would have included all of the buildings and improvements. His two–boat fishery had a successful year, but was forced to break up in late October with 52 tuns of oil and two tons of bone after running out of casks (Inq 9/6/1847; Inq 3/11/1847). It is uncertain if Thomas operated in 1848, although there is a report from the south coast that a two boat party with some Aboriginal crewmen had taken 70 tuns of oil and two tons of bone (Inq 29/11/1848).

Figure A14 Cheyne Beach Location.

The Cheyne Beach station under Thomas's management appears to have operated continuously until at least 1868 or 1869, usually with a two boat party. The exception is in 1862, when Thomas is registered for Middle Island in the Archipelago of the Recherché, while Hugh McKenzie is listed for Cheyne Beach (GG 29/7/1862). Captain Thomas Sale (1936) recalled that when he was a hand at the station during the late 1860s, Thomas would use Cheyne Beach from June to August for humpback fishing, before moving eastward to Cape Riche or Doubtful Island Bay to catch right whales.

From 1870 John Thomas is no longer mentioned in connection with whaling. The Cheyne Beach station was subsequently registered by various other operators such as Thomas Sherratt (GG 5/7/1870), Nehemiah Fisher (GG 11/7/1871; GG 4/6/1872) and John Bruce (GG 29/5/1877). 1877 is the last year that whaling is known to have occurred at Cheyne Beach, although a later source stated that when he had visited the site in 1902 he was told that operations had ceased in 1889 or 1371890 (WA 17/5/1950). This date is ten years later than the last reports of organised whaling off the south coast, but may indicate an undocumented and informal continuation of the industry.

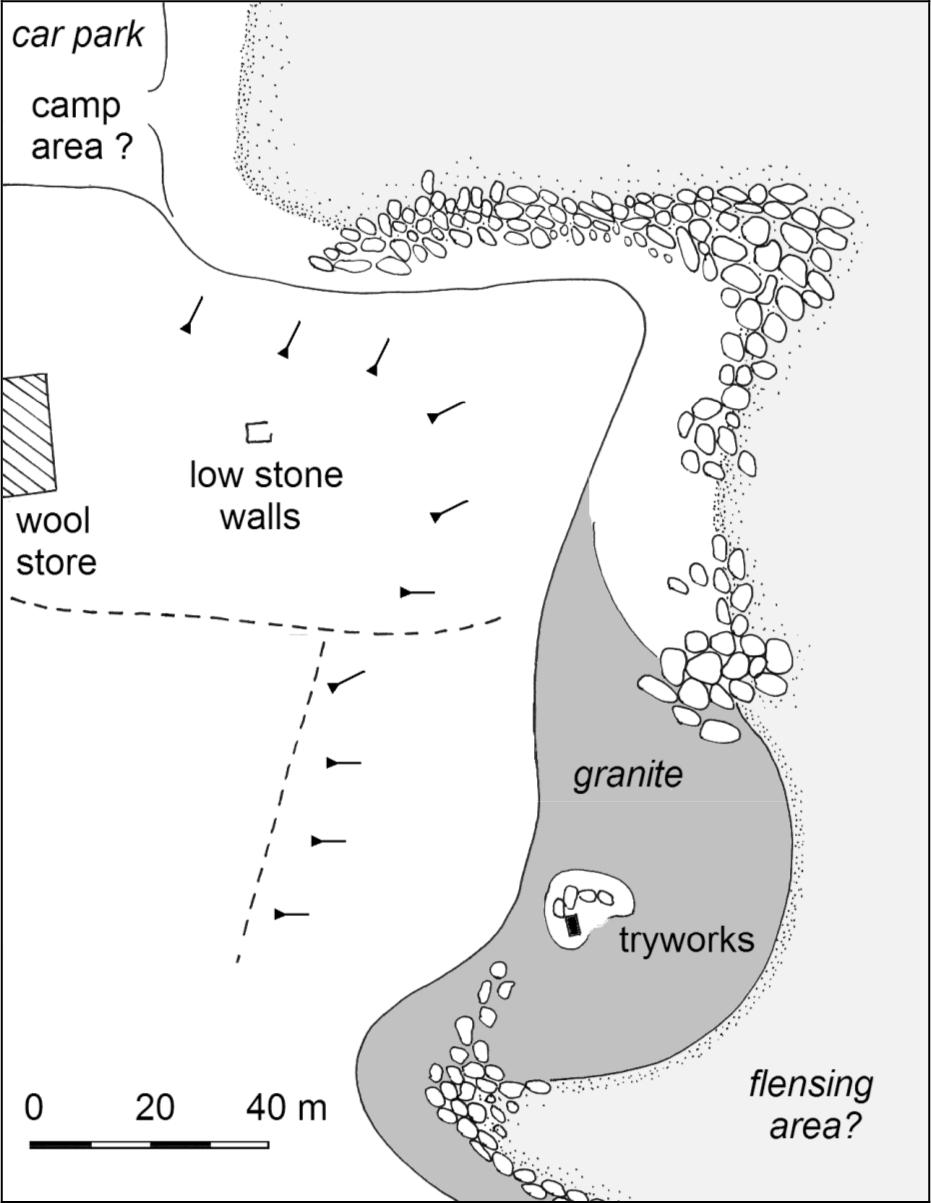

Some anecdotal information regarding the Cheyne Beach station recorded in memoirs from McKail (1927) and Sale (1936) is discussed in Chapter **. After the closure of the whaling station the anchorage was used as a transshipment point for wool from surrounding stations, and a stone and wooden wool store was constructed in the area now occupied by a car park, slightly north of the site. It is possible that the stone foundation for this building, demolished in the 1960s, was taken from the whaling station. Salmon fishermen have also used the beaches, and the immediate vicinity of the site was a popular camping site from the 1950s onwards. Further historical information on Cheyne Beach is contained in Chapter 7.

Site Description

Cheyne Beach is the southernmost portion of Hassell Beach, an extremely long, sandy bay which terminates at its northern end with Cape Riche. The orientation of the bay, the granite headland and a small reef provide protection from wind and some swell, and the bay is currently used as an anchorage by salmon fishermen.

The 1987 National Trust survey was directed to the site by long–time resident of the area, Charles ‘Snapper’ Westerberg (MacIlroy 1987). Archaeological excavations conducted as part of the current project show that there are extensive subsurface structural remains and artefact deposits in the dune area approximately 50 m south of the headland. These are described in more detail in Chapter 5.

There was no historical indication of the location of the tryworks, although there are several features suggestive of the general area. The first is a scour channel which runs adjacent to the sheltered south side of the point, forming an area deep enough to haul a whale into. Oral evidence supports this, and includes the information that small punts were used alongside the carcass as a platform for flensing (Westerberg pers. comm. 1989). There are two areas where sloping granite sheets might have aided the process. The first is towards the end of the point, and has a level area above it which might have served as a working surface. Although there is ash and material shown in shallow erosion area, there is no clear evidence for a tryworks. A similar granite sheet is seen closer to the shore, although the area above this has been cleared and altered by modern fishermen to include a concrete floor. The final option is that the blubber was hauled up to a tryworks on the main beach, although no physical evidence was found to support this.

Historical information suggests that the look–out was on the ridge of the hill to the north of the site (McKail 1927; Albany Mail 18/12/1889), with the probable location being the large granite boulder at the peak of this. Although it was not possible to detect deliberate working of the stone, there is a small ledge near the top of the boulder which proves to be an ideal seat for anyone watching towards Hassell Bay and the open sea. No artefacts were visible around the base of the boulder. Large sections of whalebone can be seen along the shore at Cheyne Beach, and local fishermen state that these are often dredged up by the sea after heavy storms. Further information on the Cheyne Beach site is contained in Chapters 5–7.

CAPE RICHE

Date Range: 1870–1872+

Location: Southern end of Cheyne Bay, 3 km northwest of Cape Riche.

1:100,000 AMG Reference: 2628 Cheyne 606–701

History

As early as 1835 there was an application to use of Cape Riche as a whaling station, with Henry Ommaney applying for a grant of 2650 acres including the adjacent island (Cheyne Island), ‘it being a very desirable and eligible situation for a whaling establishment which I contemplate shortly commencing’ (CSR 46/20: 10/12/1835). The application was refused, despite Ommaney's appeals (CSR 46/22: 4/5/1836).

In 1842 Albany merchant George Cheyne established his homestead and an independent supply base for foreign whaling vessels at Cape Riche, providing ‘water, fuel, vegetables and fresh meat, and other necessaries… at moderate prices’ (PG 18/11/1843; Stephens 1951). The operation was a bold and astute move which proved highly successful, allowing the masters to avoid paying the excessive harbour fees of Western Australian ports and minimising the risks of desertion and drunkenness that arose on visits to settlements. The safe anchorage also made the area attractive to American and French vessels wintering and bay–whaling (Inq 6/11/1844; Inq 9/9/1846; Inq 7/7/1852).

Sale (1936) suggests that John Thomas from Cheyne Beach may have begun using the location as a late season station in the late 1860s, long after its demise as an independent port. The first firmly recorded use was in 1870, when John MacKenzie registered a two–boat party for that location, probably using it as his early season station (GG 5/7/70). The Inquirer also commented that Mr. MacKenzie was ‘occupying his old berth at Cape Riche’, implying an earlier association (Inq 20/7/1870). Two years later another party with 12 men was registered for that site by Cuthbert MacKenzie, although by early September they had returned to Albany, having taken only one small whale yielding 2 tuns of oil (GG 4/6/1872; Her 7/9/1872). The same report notes that they would depart the following week for the head of the Great Australian Bight ‘in order to be in time for the right whale season’.

138After this time registrations tended to be for ‘east coast’ stations, although it is possible that Cape Riche was still used.

Figure A14 Cape Riche Site Plan.

Site Description

The site of the whaling station is 3 km northwest of Cape Riche at the end of Cheyne Bay, opposite Cheyne Island. These topographic features form a sheltered anchorage used during the late 19th and early 20th centuries as a transshipment point for wool from farms in the area. A late 19th century wool store has survived on the ridge above the sheltered sandy beach and it is probable that the whaling station camp would have been located nearby, possibly in the area now occupied by the modern campsite. No evidence of the campsite was located, although footings of later buildings related to salmon fishing are evident.

Approximately 160 m eastward of the car park is a granite shelf sloping up from a slightly protected area. Thirty five meters above the high tide mark is a small island of soil and vegetation which appears to contain the remains of a stone tryworks. Measuring 2.10 m (N.E. to S.W.) by 1.10 m, only the lower 30 cm of the structure remains. It did not prove possible to locate ash or other products of the trywork process in or around the structure, although access to internal deposits was limited by the overburden of rubble. A small trypot is located in the front garden of nearby Cape Riche station, although the Moir family (the long–term owners) has no specific knowledge of its origin other than it being from the whaling station.

Although it was not possible to visit Cheyne Island, historical records suggest it may contain archaeological features. A survey of Cape Riche by F.T. Gregory in 1849 includes one sighting from the Cape to a ‘whaler's lookout’ on Cheyne Island (Gregory 1850). As this predates the colonial use of the area it is probable that the look–out was for the foreign vessels anchored in Cheyne Bay. Reminiscences by Laurance Gorman, a member of McKenzie’s 1870 whaling party, describe the graves of three French whalers on Cheyne Island, which he refers to as Oars Island, as well as several engravings on the granite including the date ‘1764’ and ‘18 tuns’ (AA 22/8/1829).

DOUBTFUL ISLAND BAY

Date Range: 1836–1838, 1863–1870s

Location: Corner Cove (House Beach), southern edge of Doubtful Island Bay.

1:100,000 AMG Reference: 2829 Hood Point 322–943

History