1

Introduction

As 19th-century Melbourne was growing into the vibrant, global city that it would ultimately become, immigrants seeking a new way of life and prosperity were negotiating their status in the new colony. From the time of the earliest settlers to the gold rush and beyond, people from various class backgrounds with different aspirations navigated their way through fluid social structures in order to succeed and establish their position in the new colony. Class in Australia was not a fixed structure, but was flexible and often differed from the norms of British society, with which the majority of immigrants were familiar (Russell 2010:114, 126). Social mobility was possible in the colonies, and indeed was one of the drawcards for people immigrating to Australia (Fitzgerald 1987). The impact of this mobility on class structure and society has been much debated by historians (Neale 1972; Davison 1978; Connell and Irving 1980; Hirst 1988; Thompson 1994; Young 2003; Russell 2010) and is an important question for historical archaeology.

In order to examine the distinctive class structure that emerged in Melbourne in this period, this archaeological study tests the hypothesis that the material culture of different immigrant groups will be distinctive from each other. Further, by understanding gentility as a form of cultural capital, these differences can be interrogated to examine class negotiation. By doing so, it contributes to current historical archaeology in three important ways: first, by providing a detailed analysis of middle-class material culture with a view to contextualising previous historical archaeological research on Melbourne’s working class; second, by providing a benchmark for further research on the diverse middle class; and third, by identifying links between material culture and class through which class negotiation can be examined.

The material culture that forms the basis of this study was recovered from the Viewbank homestead site by Heritage Victoria in 1996 and 1997. This assemblage was discarded over time by the Martin family who occupied the genteel homestead from 1843 to 1874. The family were typical of many early arrivals to Port Phillip. From a solid middle-class background, they brought with them capital and ambition. They were poised to take a role of influence in the new colony, and indeed they did. Dr Martin channelled the family wealth into pastoral pursuits with great success, while Mrs Martin set about establishing a genteel household. The Viewbank assemblage provides a unique insight into the role that material culture played in establishing the position of the Martin family in Melbourne society.

URBAN ARCHAEOLOGY IN AUSTRALIA

Research in Australian historical archaeology has steadily grown since the 1970s and has made many notable contributions in the areas of convictism, culture contact, industry and urbansim (see Connah 1993; Lawrence and Davies 2011). Notable among these studies are the large scale excavations of the inner-city ‘slum’ areas of The Rocks, Sydney (Lydon 1998, 1999; Consultants 1999; Karskens 1999, 2001; Crook et al. 2003; Crook and Murray 2004) and ‘Little Lon’/Casselden Place, Melbourne (McCarthy 1989; Mayne and Lawrence 1998; Murray and Mayne 2001; Murray 2006, 2011). In both studies, material culture has been used to present a more nuanced picture of life in the ‘slum’ and argued for a sense of community in these areas with many residents striving for respectability (Karskens 2001; Murray and Mayne 2001). Other studies on urban working-class sites include Jane Street, Port Adelaide (Lampard 2004, 2009; Lampard and Staniforth 2011) and a number of unpublished cultural heritage management projects.

To date, no similar studies have centred on middle-class domestic occupation in the urban or suburban context, largely because such sites are located in suburban areas where commercial development is less frequent and is less likely to require excavation for cultural heritage management purposes. Although a number of studies have been conducted on stately homes (Frankel 1979; Watts 1985), rural estates (Connah 1977, 1986, 2001, 2007; Connah et al. 1978) and on Government Houses in Sydney (Proudfoot et al. 1989; Casey 2005), the middle class is underrepresented, especially in the area of material culture studies. Only three studies have involved a primary focus on middle-class material culture: Paradise in the Queensland Goldfields (Quirk 2008), Willoughby Bean’s parsonage in regional Victoria (Lawrence et al. 2009) and the aspirational middle-class Thomas household at Port Albert (Prossor et al. 2012).

Since the completion of The Rocks and Little Lon projects there have been numerous calls for middle-class material culture studies (Lawrence 1998:13; Murray and Mayne 2001:103; Karskens 2and Lawrence 2003:100–101; Crook et al. 2005:27; Crook 2011:592; Murray 2011:578). To successfully interpret assemblages and study class differences, it is essential to study the full range of class positions and consumer behaviour (Praetzellis et al. 1988; Karskens and Lawrence 2003:101). This study represents a major contribution towards fulfilling this objective in the Australian urban context.

CLASS, MATERIAL CULTURE AND GENTILITY

The interrelations of class, material culture and gentility are at the centre of this study. Class is a key concept in the social sciences for good reason: it attempts to explain social change and stability in the past and is central in historical archaeology (Paynter 1999:184–185). It is particularly pertinent to the study of the colonial world where ideologies and social structures were being adapted to new environments, and is vital to understanding social relations in the past and ultimately society today.

Class, in spite or perhaps because of its centrality to understanding society, is a difficult and nebulous concept. This in large part is due to confusion over class as an arbitrary category or tool used by the researcher for analytical purposes, and class as a real (and reconstructable) mark of identity (Davidoff and Hall 2002:xxx; Mrozowski 2006:13; Tarlow 2007:27). The many and varied approaches to class in the social sciences are outside the scope of this study to review. Instead the focus is on class in historical archaeology.

Interest in class as a theme in historical archaeology has been growing since the 1990s. Internationally, a number of studies have addressed class in relation to capitalism (e.g. Paynter 1988; Johnson 1996; Leone 1999; Leone and Potter 1999; Mrozowski 2006), ideology (e.g. Burke 1999; Leone 2005), power (e.g. Lucas 2006), domination and resistance (e.g. Beaudry et al. 1991; Miller et al. 1995), manners (e.g. Goodwin 1999), improvement (Tarlow 2007), gender (e.g. Hardesty 1994; Wall 1994; Rotman 2009), or workingclass living conditions (e.g. Mrozowski et al. 1996; Karskens 1999; Mayne and Murray 2001; Yamin 2001). In these studies, class often takes a secondary position to the theme being discussed (Wurst and Fitts 1999:1–2). A number of scholars, however, have highlighted the potential of using historical archaeology to examine class differences, social mobility and class conflict (e.g. Reckner and Brighton 1999; Praetzellis and Praetzellis 2001; Casella 2005; Griffin and Casella 2010; Brighton 2011).

Studies of class in Australian historical archaeology have generally been driven by discussions of respectability and gentility. The majority focus on the working class and view respectability as a unique and defining characteristic of that group (e.g. Lydon 1993a; Karskens 1999; Lawrence 2000; Lampard 2004). Other studies have focused on gentility (Quirk 2008; Lawrence et al. 2009), or in some cases respectability (Lampard and Staniforth 2011), as a social strategy used to project middle-class status.

Historical archaeologists have predominantly viewed class as a hierarchical scale through which people and their lifestyles can be described (Wurst and Fitts 1999:1; Wurst 2006:191, 197; Lawrence and Davies 2011:252–253). This standpoint holds that class existed in the past and through observation can be defined and reconstructed by researchers based on empirical evidence from the past. In historical archaeology, this works well at the individual site level, but has limitations for comparative studies between classes where nuanced differences between groups of people make accurate attribution to the hierarchy problematic. When seeking to compare sites, it is beneficial to treat class as a relational concept (Wurst and Fitts 1999:1; Wurst 2006:191). In doing so, such issues as social formation, class negotiation and social change can be more critically examined. While this study is not comparative, one of the major objectives of the research is to develop a framework to facilitate comparative research.

Material culture has significant potential to contribute to the study of class. The important contribution of historical archaeology to material culture studies began in the 1970s and 1980s with the formalisation of historical archaeology as a distinctive discipline within archaeology (e.g. Deetz 1977; Schlereth 1979; Hodder 1982; Miller 1985, 1987). Since the early scientific studies of artefacts (e.g. South 1977), and the structuralist search for meaning (e.g. Glassie 1975; Deetz 1977; Glassie 1982), material culture studies in historical archaeology have become increasingly interpretative and multidisciplinary (e.g. Miller 1987, 1995; Cochran and Beaudry 2006:193).

Using the early capitalist economy and emerging globalisation as the contexts for their research questions, historical archaeologists have increasingly turned to studies of consumerism. The essential principles in the anthropological study of consumerism are relevant to the present study, namely that goods can be regarded as texts that are open to multiple readings, and that consumer choices have symbolic meaning (Douglas and Isherwood 1978; McKendrick et al. 1982; Appadurai 1986; Miller 1987, 2008, 2010; Spencer-Wood 1987; McCracken 1988; Friedman 1994). Studies of consumerism have remained popular in historical archaeology and have further developed ways of viewing the social meanings of commodities in society (e.g. Orser Jr. 1994; Gibb 1996; Wurst and McGuire 1999; Majewski and Schiffer 2001).

Linked with consumer studies, the theory of social practice developed by French cultural theorist Pierre Bourdieu (1977, 1984) has become increasingly popular in historical archaeology (e.g. Wall 1992; Lawrence 1998:8; Mayne and Lawrence 1998; Shackel 2000:233; Praetzellis and Praetzellis 32001; Russell 2003; Young 2004; Rotman 2009). Bourdieu’s theorisation of how goods actively pass on and structure culture has obvious appeal and application in interpreting artefacts. Further, Bourdieu suggests that a pivotal determining factor in an individual’s judgement of their class is cultural capital. Webb, Shirato and Danaher (2002:x) provide a useful definition of cultural capital: ‘a form of values associated with culturally authorised tastes, consumption patterns, attributes, skills and awards’. Class distinction is thus ‘most marked in the ordinary choices of everyday existence, such as furniture, clothing or cooking …’ (Bourdieu 1984:77). Bourdieu (1977) argues that habitus is the deliberate and subconscious understanding of the behaviours and practices appropriate to one’s place in society. It is not imposed, but is continually changing depending on the values and opinions of self and others. With the idea of cultural capital, Bourdieu’s theory of habitus is a useful tool for archaeologists seeking to understand the material cultural pattern of a particular group. These ideas of practice and interaction allow interpretations to be made on how people negotiated, changed and maintained their position in society (see Casella and Croucher 2010:2).

A number of researchers in both archaeology and history have usefully linked gentility with Bourdieu’s concept of cultural capital (e.g. Praetzellis and Praetzellis 2001:647; Russell 2003:168; Young 2004). The ideals associated with gentility were refinement, good taste, manners, morality, religious observance, avoidance of idleness, constructive leisure and domesticity (Russell 1994:60; Marsden 1998:2; Mitchell 2009:261–266). As an emic value, used by people of the era, genteel was a term to describe people, goods, furniture, houses, suburbs, behaviours and values according to these ideals.

It has been argued that genteel behaviour and appearance became the measure of status for the middle class (Davidoff and Hall 2002:398; Young 2003:4–5), and further that in Australia, gentility was even more important in forming and maintaining status than in Britain (De Serville 1991:2). Historian Penny Russell’s (1994) study of the ‘colonial Victorian gentry’ argued that gentility was crucial in determining status in a situation of greater social mobility where family background was often uncertain. She emphasised genteel performance, good manners and good taste as necessary to enable those in the ‘gentry’ to understand who belonged (Russell 1994:14–15).

The nature of gentility is such that it leaves its mark in the archaeological record. Despite the fact that the actual practice of genteel behaviour is not represented in the archaeological record, the beliefs and values associated with gentility can be interpreted through the goods people purchased for their homes and themselves. The type, quality and quantity of domestic and personal objects purchased by a group of people can be interrogated to interpret the values, customs and position of the people who purchased them. In this way, the archaeological record can reveal something of the values, manners and behaviours associated with gentility (see Ames 1978; Goodwin 1999).

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

For the purpose of this study, class is treated as an arbitrary category used to examine the similarities and differences between groups of people in order to examine social formation. The terminology of working, middle and upper class is used but these groups are treated as flexible and fluid. While wealth, occupation, religious belief, ethnicity and gender are all acknowledged as contributing to class position, cultural capital is the main focus. Gentility is used here as an analytical tool which operates separately to class; as one brand of cultural capital that could be adopted, appropriated or adapted by different groups in different ways for different purposes. In this way, gentility as viewed through material culture is used to examine class structure and negotiation in Melbourne.

The approach of treating class as an arbitrary category in order to understand society has certain advantages. This way of understanding has long been espoused in social theory (Foucault 1973; Giddens 1973; Bourdieu 1977), but is rarely applied in archaeology. However, the emphasis that this approach places on the examination of the similarities and differences of the lifestyles of people using the idea of class has great potential in archaeology, particularly where comparative studies are concerned. Bourdieu’s (1977, 1984) concept of cultural capital is used here as a metaphor rather than an empirical descriptor, useful for identifying the roles particular groups played in class formation (Moi 1991; Skeggs 1997:10). Further, this approach acknowledges the effect of the researcher on interpretations and the limitations of descriptions of the past which are subject to the complexities of truth, bias and interpretation, but still allows class to be used as a concept in order to contribute to knowledge of society in the past.

Another advantage of focusing on gentility as cultural capital is that it acknowledges the role of women in determining class. One limitation of the study of class is that it can overlook women, with their class position merely assumed based on the wealth or occupation of their husband or father. While this was to some degree the reality of the 19th century for many women, there are also instances where single, widowed or divorced women negotiated their class position autonomously. Women played a vital role in gentility and genteel performance (Bushman 1993:281; Russell 1994:14), and when emphasising gentility as cultural capital the class position of women, along with their role in negotiating status, can be articulated independently. 4

The objective in this study is not to accurately attribute people to a point on the hierarchy and describe their lifestyle, but to arbitrarily group people in order to use the concept of class to understand the role of these groups in formulating and changing society. To facilitate this, immigrants to Melbourne are divided here into artificial groups based on similarities in their class backgrounds, generation, time of arrival in the colony and lifestyle once in the colony. This is not an attempt to create an alternative hierarchy, but rather to group like immigrants in order to examine the formation of class in the new colony.

The group that is the focus of this study is the ‘established middle class’, defined as early settlers and colonists of middle-class backgrounds who brought their gentility and privilege with them to the new colony. This group includes middle-class men, particularly those who were not in line for an inheritance, seeking adventure and independent livelihoods in the colonies. Many of the first wave of arrivals in this group included doctors, lawyers, clergy or ex-military men from good families. Most of these immigrants were English or Scottish, with smaller numbers of well-connected Irish (Broome 1984:23; De Serville 1991:3–4). Many of these men established significant wealth through business or vast pastoral properties, which brought corresponding economic and political power. Women of middle-class backgrounds immigrated to the colonies with their families or husbands, or as single women in a bid to improve their prospects for employment or marriage (Hammerton 1979:11–12; Gothard 2001:53–54). Many of the families in this group became dynasties that endured throughout the century (Broome 1984:23, 39). The ‘established middle class’ had a firm position of authority in the colony, however this was challenged initially by those of working-class or convict backgrounds arriving at the same time and seeking entry to their ranks, and later again by the influx of people brought by the gold rush (Russell 1994:15, 2010:113; Young 2010:136).

The assumption that social distinctions manifest in material culture is a basic premise of historical archaeological discourse (e.g. Deetz 1977; Glassie 1977; De Cunzo and Herman 1996; Leone 1999; Mayne and Murray 2001; Mrozowski 2006) and of this study. When the focus of research is on reconstructing identity or individual consumer choice, it can be difficult to distinguish class from other factors such as gender, ethnicity and socio-economic status (Wurst and McGuire 1999; Rotman 2009:1; Casella and Croucher 2010:2–3; Shackel 2010:58–60). By shifting the focus from reconstructing identity or accurately attributing people to a point on a hierarchy, however, class becomes a useful concept for articulating the distinctions between people and examining society.

Drawing on the theory of gentility as cultural capital (see Praetzellis and Praetzellis 2001:647; Young 2004:202), it is argued here that the distinctive lifestyles of the ‘established middle class’ and other groups of immigrants would be reflected in their material culture. Gentility formed one of the primary driving forces of consumerism at this time, and also formed an important domain of social practice to define status within society. It should not be assumed, however, that gentility was adopted by different groups of people in the same ways and for the same reasons (Praetzellis and Praetzellis 2001:647). When considering gentility as an analytical tool for research, it is useful to view it as operating separately to class, as a cultural capital that could be adopted, appropriated or adapted by different groups in different ways for different purposes. While gentility may have sometimes served as a tool in social mobility, it may not have done so in other cases (Karskens 2001:77; Praetzellis and Praetzellis 2001:647; Casella 2005:167–168).

The different uses of gentility are, therefore, indicative of changing social boundaries and class structures in 19th-century Melbourne. It is anticipated that different groups will have distinctive patterns of material culture depending on their distinctive uses of gentility, and that this can be used to interpret class structure and negotiation in the colony. For the ‘established middle class’ it is expected that gentility would be performed and displayed as an inherent, as opposed to learnt, behaviour and should, therefore, signal how members of this group were maintaining and defining their status in the changing social landscape of early colonial Melbourne. Such differences can be used to articulate class negotiation, particularly as more studies from more groups emerge.

The scope of this project dictates a focus on one archaeological site (Viewbank homestead) and one historical family (the Martins) as being representative of the ‘established middle class’. It is important to note that while individual stories do not add up to represent the sum of colonial history, they can help us to understand it better (Russell 2010:14). When combined with the material record such stories can be used to explore the changing nature of class in society (Mrozowski 2006:1). While this study cannot fully examine class formation in 19th-century Melbourne, it emphasises the relational nature of class with a view to further research.

VIEWBANK HOMESTEAD

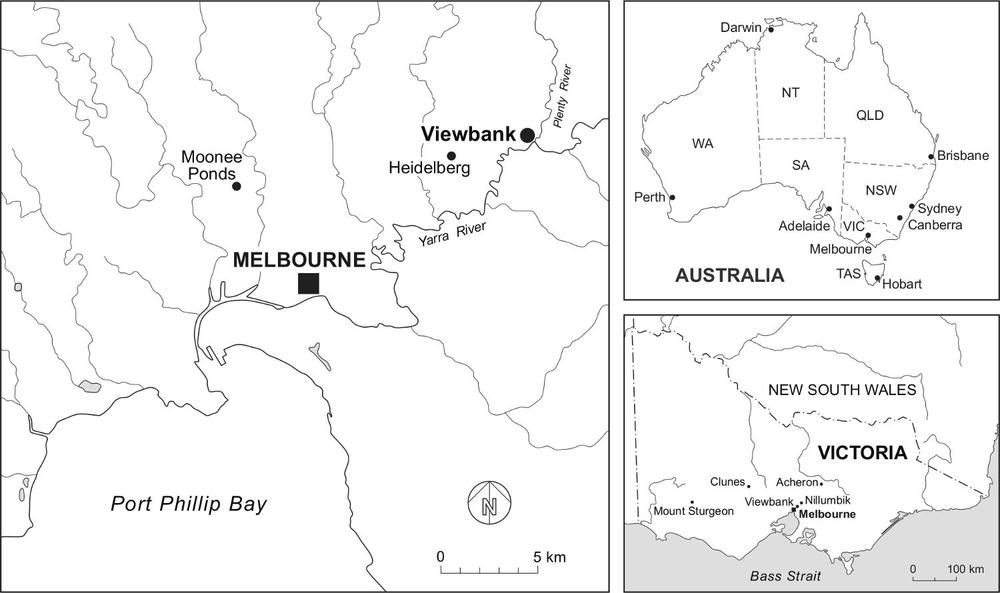

The Martin family arrived in Sydney and travelled overland to Melbourne in 1839, only four years after permanent European settlement commenced (Bride 1969:87). Dr Robert Martin, his wife Lucy and their four children lived initially at Moonee Ponds prior 5to moving to Viewbank homestead in 1843 (Port Phillip Gazette, 22 May 1843) where two more children were born. The family occupied Viewbank (along with a number of servants) until Dr Martin’s death in 1874. The grand homestead and generous allotment of land was located in the genteel settlement of Heidelberg, 15 kilometres north-east of Melbourne, Victoria (Figure 1.1). Dr Martin had been trained as a physician in Britain, but once in Australia he became a successful and wealthy pastoralist. The Martin family were influential and well respected in the new colony. They were typical of the ‘established middle class’ group and provide a compelling case study.

Figure 1.1: Location of Viewbank homestead (Source: Ming Wei).

The Viewbank site is significant as a rare example of a middle-class archaeological site close to a city centre which has remained undeveloped and relatively undisturbed. Its location in the Melbourne Metropolitan Park along the Yarra River has ensured the relative protection of the archaeological remains. This is unusual for middle-class homes which are often in suburban areas that have been continuously occupied to the present date. Any cesspits are located in present day backyards and are generally not accessible to archaeologists. This makes Viewbank a rare opportunity to study the material culture of the middle class. Heritage Victoria excavated the homestead, adjacent tip and possible outbuildings over three seasons from 1996 to 1999. For the purposes of this study, the artefact assemblage provides an extensive sample of middle-class material culture from the 19th century.

OUTLINE OF THE STUDY

This study uses historical and archaeological methods to examine the lives and lifestyles of the residents of Viewbank as the basis for the examination of class negotiation. The remainder of the study is comprised of three major parts: first, historical and archaeological evidence; second, interpretations on the role of gentility in the material culture and lifestyles of the Martins; and third, discussion linking this evidence to Melbourne’s class structure.

The first section commences with chapter 2 which presents Melbourne’s early history and the history of Viewbank homestead. This is followed by chapter 3 in which the first major component of the evidence for the study is presented, namely the personal histories of the people living at Viewbank. These histories are told for Dr Martin, Mrs Martin, their children and the servants working at Viewbank. Particular attention is paid to the background of the Martins and their success once in Melbourne. Chapter 4 follows with details of the excavations conducted by Heritage Victoria and the post-excavation artefact work undertaken by the author. This includes a discussion of the artefact processing and cataloguing methods. In chapter 5 the second major component of evidence is presented with the analysis of the material culture. Analysis focuses on domestic, kitchen, personal, recreational, work related and social items. The depositional patterns that inform the interpretation of the artefacts are also examined. 6

The second section commences in chapter 6 with a detailed examination of the acquisition of goods at Viewbank homestead: namely, the trade networks and shopping habits that are indicated by the archaeological and historical evidence. Following this, drawing on both the archaeological and historical evidence, the lives and lifestyles of the people at Viewbank homestead are discussed in detail in chapter 7 including work, leisure, dining, social events, religion, childhood, and genteel appearance and health. The house and grounds are also considered as material culture that can inform an understanding of life at the homestead.

The discussion in chapter 8 characterises the material culture recovered from Viewbank homestead and the assemblage is examined for expressions of gentility and characterised in terms of variety, level of cohesion in public and private aspects of the assemblage, type of expensive or luxury goods and degree of fashion and good taste. It then goes on to explore how gentility can be viewed as functioning in a distinctive manner for the ‘established middle class’ with interpretations made on how this group was defining and maintaining their position in the new colony.